Pacific north coast integrated management area plan

Table of Contents

- Preface

- Executive Summary

- List of Acronyms and Initialisms

- Acknowledgements

- 1.0 Plan Context

- 2.0 The Planning Area

- 3.0 The Planning Process

- 4.0 Ecosystem-Based Management Framework

- 5.0 Implementation

- References

- Glossary of Terms

- Appendix 1 Federal and Provincial Legislative and Regulatory Summary Tables

- Appendix 2 PNCIMA Supporting Documents

- Appendix 3 Marine Activity Profiles and Future Outlook

- Appendix 4 Maps

- Appendix 5 Committees and Participants

- Appendix 6 Record of Meetings

- Appendix 7 Valued Ecosystem and Socio-economic Components

- Figure 2-1 Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA)

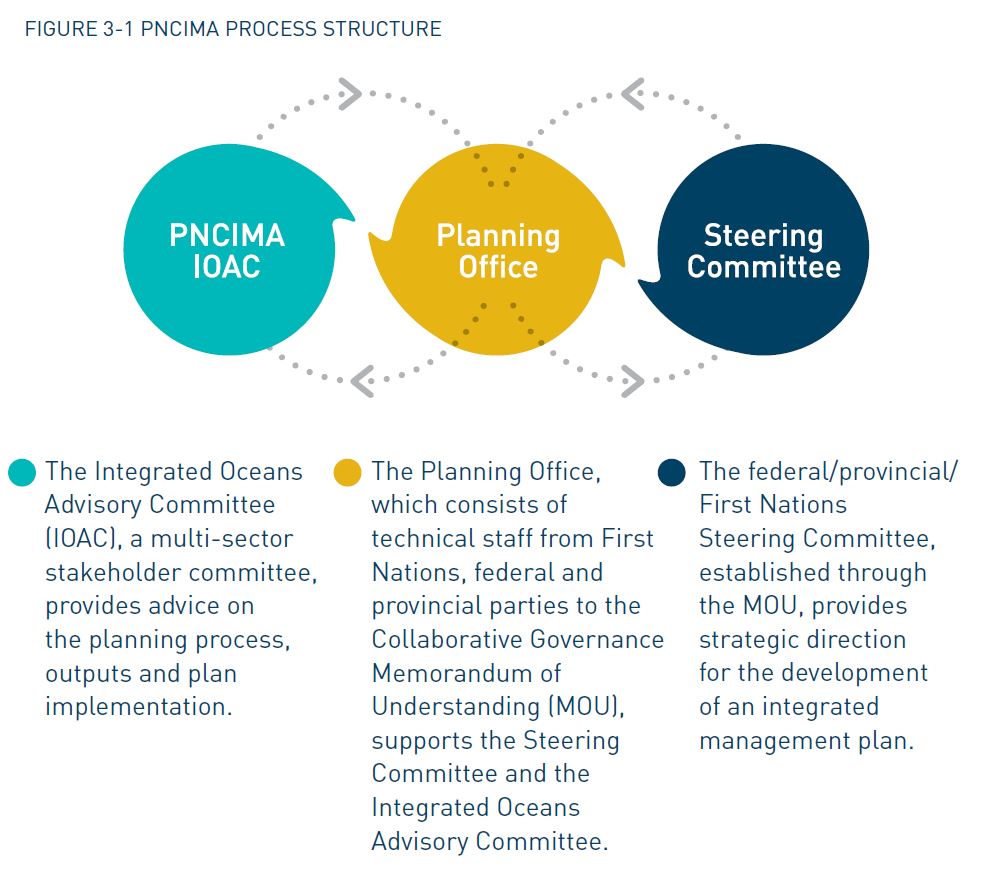

- Figure 3-1 PNCIMA Process Structure

- Figure 3-2 Options for Participating in the PNCIMA Process

- Figure 3-3 PNCIMA Timeline

- Figure 4-1 Components of the PNCIMA Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) Framework

- Figure A7-1 Process for Identifying Valued Ecosystem Components

- Figure A7-2 Realms of the Socio-economic System

- Table 2-1 Communities in the Coastal Watersheds in PNCIMA

- Table 4-1 Goals, Objectives and Strategies for PNCIMA

- Table A1-1 Federal Agencies with Direct Roles in Ocean Management in PNCIMA

- Table A1-2 British Columbia Agencies with Direct Roles in Ocean Management in PNCIMA

- Table A3-1 Summary of Marine Activity Profiles and Future Outlook

Appendices

List of figures

List of tables

Dear reader,

On behalf of the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA) Steering Committee, we are pleased to present the Integrated Ocean Management Plan for the Pacific North Coast area.

This document provides high-level direction on the planning and management of marine activities and resources in the area, and has been developed with extensive input from a broad range of partners, including First Nations, provincial and federal governments, industry, non-governmental organizations, academia and local community residents.

We would like to thank the many individuals and partners who collaborated in the development of this plan. Their experience and perspectives have proven invaluable in creating a comprehensive, strategic framework to support a more holistic and integrated approach to ocean use in PNCIMA.

Ongoing participation, support and commitment from partners and stakeholders in implementing this plan will help ensure that healthy and functioning ecosystems and coastal communities are maintained in this significant and unique marine area.

Sincerely,

Dominic LeBlanc

Minister

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Steve Thomson

Minister

BC Ministry of Forests, Lands, & Natural Resource Operations

Marilyn Slett

President

Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative

- As directed by:

- Council of the Haida Nation (also representing Old Massett Village Council and Skidegate Band Council)

- Gitga’at Nation

- Heiltsuk Nation

- Kitasoo/Xai’Xais Nation

- Metlakatla First Nation

- Nuxalk Nation

- Wuikinuxv Nation

Robert Grodecki

Executive Director

North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society

- Gitxaala First Nation

- Metlakatla First Nation

- Kitsumkalum First Nation

- Kitselas First Nation

This plan is not legally binding and does not create legally enforceable rights between Canada, British Columbia or First Nations. This plan is not a treaty or land claims agreement within the meaning of sections 25 and 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982.

This plan does not create, define, evidence, amend, recognize, affirm or deny any Aboriginal rights, Aboriginal title and/or treaty rights or Crown title and rights, and is not evidence of the nature, scope or extent of any Aboriginal rights, Aboriginal title and/or treaty rights or Crown title and rights.

This plan does not limit or prejudice the positions Canada, British Columbia or First Nations may take in any negotiations or legal or administrative proceedings.

Nothing in this plan constitutes an admission of fact or liability.

Nothing in this plan alters, defines, fetters or limits or shall be deemed to alter, define, fetter or limit the jurisdiction, authority, obligations or responsibilities of Canada, British Columbia or First Nations.

Executive Summary

The Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA) is one of five national Large Ocean Management Areas identified in Canada’s 2005 Oceans Action Plan. The PNCIMA plan is the product of a collaborative process led through an oceans governance agreement between the federal, provincial and First Nations governments, and contributed to by a diverse group of organizations, stakeholders and interested parties. The plan is high level and strategic, and provides direction on and commitment to integrated, ecosystem-based and adaptive management of marine activities and resources in the planning area as opposed to detailed operational direction for management.

The plan outlines a framework for ecosystembased management (EBM) for PNCIMA that includes assumptions, principles, goals, objectives and strategies. This EBM framework has been developed to be broadly applicable to managers, decision-makers, regulators, community members and resource users alike, as federal, provincial and First Nations governments, along with stakeholders, move together towards a more holistic and integrated approach to ocean use in the planning area.

PNCIMA’s EBM goals are interconnected and cannot be taken as separate from one another. The purpose of the PNCIMA EBM framework is to achieve:

- integrity of the marine ecosystems in PNCIMA, primarily with respect to their structure, function and resilience

- human well-being supported through societal, economic, spiritual and cultural connections to marine ecosystems in PNCIMA

- collaborative, effective, transparent and integrated governance, management and public engagement

- improved understanding of complex marine ecosystems and changing marine environments

The plan also provides an information base and a number of management tools that can be used by other parties to facilitate the application of EBM at a variety of scales in PNCIMA.

Five priorities are identified for short-term implementation of the plan:

- governance arrangements for implementation

- marine protected area network planning

- monitoring and adaptive management

- integrated economic opportunities

- tools to support plan implementation

Implementation is the shared responsibility of all signatories to the planning process and will be undertaken within existing programs and resources, where possible.

To address plan performance monitoring and evaluation, indicators will be developed to monitor and evaluate plan outcomes, and comprehensive reviews will be undertaken to assess progress in achieving the EBM goals and objectives. Findings from the performance evaluation, along with emerging management needs and priorities, will be considered and, where appropriate, incorporated into implementation so that the plan reflects changing circumstances and conditions as they arise.

The PNCIMA data collection phase occurred between 2007-2012. The data, statistics and trends referenced in the document reflect the best information available during that timeframe.

List of Acronyms and Initialisms

The following acronyms and initialisms are used in the context of integrated oceans management for PNCIMA:

- B.C.

- British Columbia

- DFO

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- EBM

- Ecosystem-based management

- EBSA

- Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area

- IOAC

- Integrated Oceans Advisory Committee

- LOMA

- Large Ocean Management Area

- MaPP

- Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- MPA

- Marine protected area

- PNCIMA

- Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area

Acknowledgements

The Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA) plan represents the culmination of several years of dedicated work by dozens of people who represent marine sector interests as well as First Nations, provincial and federal governments.

The governance partners of the PNCIMA initiative, including Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Province of British Columbia, the Coastal First Nations, and the North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society would like to recognize and thank the following individuals who played key roles in providing technical support, direction and oversight on the production of this document:

- Aaron Heidt

- Alex Chartrand

- Allan Lidstone

- Amy Wakelin

- Andrew Johnson

- Andrew Mayer

- Angela Stadel

- Averil Lamont

- Barry Smith

- Blair Hammond

- Bonnie Antcliffe

- Brenda Gaertner

- Bruce Reid

- Bruce Watkinson

- Candace Newman

- Caroline Butler

- Caroline Wells

- Catherine Rigg

- Celine Menard

- Charles Hansen

- Charlie Short

- Chris McDougall

- Chris Picard

- Chris Wilson

- Christie Chute

- Coral Keehn

- Craig Outhet

- Cristina Soto

- Dale Gueret

- Danielle Shaw

- David Leask

- Dayna Leganchuk

- Denise Zinn

- Diana Freethy

- Doug Neasloss

- Erin Mutrie

- Evan Putterill

- G. Les Clayton

- Garry Wouters

- Gary Alexcee

- Gary Wilson

- Glen Rasmussen

- Gordon McGee

- Graham van der Slagt

- Greg Savard

- Harry Nyce Sr.

- Hilary Ibey

- Hilary Thorpe

- James Boutillier

- Jas Aulakh

- Jason Thompson

- John Bones

- Joy Hillier

- Julie Carpenter

- Karen Topelko

- Kate Ladell

- Keeva Keele

- Kelly Francis

- Ken Cripps

- Kendall Woo

- Kevin Conley

- Kyle Clifton

- Lara Sloan

- Larry Greba

- Leri Davies

- Marc-Andre deLauniere

- Masoud Jahani

- Matthew Justice

- Maya Paul

- Megan Mach

- Mel Kotyk

- Miriam O

- Neil Davis

- Nicholas Irving

- Nicole Gregory

- Peter Johnson

- Rebecca Martone

- Rebecca Reid

- Rob Nelles

- Robert Grodecki

- Ross Wilson

- Russ Jones

- Sean MacConnachie

- Sheila Creighton

- Siegi Kriegl

- Sophie Tee

- Spencer Siwalace

- Steve Diggon

- Tanya Punjabi

- Terrie Dionne

- Terry Collins

- Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson

- Trevor Russ

- Verne Jackson

- Wally Webber

- Whitney Lukuku

- Whitney Sadowsky

- Wilfred Dawson

The PNCIMA initiative governance partners would also like to recognize the following individuals who provided guidance to the planning process and its outputs through their involvement in the Integrated Oceans Advisory Committee:

- Al Huddlestan

- Alan Thomson

- Andrew Webber

- Arnie Nagy

- Bill Johnson

- Bill Wareham

- Bob Corless

- Brad Setso

- Brian Lande

- Bruce Watkinson

- Christa Seaman

- Christina Burridge

- Craig Darling (Facilitator)

- Dan Edwards

- David Minato

- Des Nobels

- Doug Aberly

- Evan Loveless

- Heidi Soltau

- Jeremy Maynard

- Jessica McIlroy

- Jim Abram

- Jim McIssac

- John MacDonald

- Kaity Stein

- Ken MacDonald

- Kim Johnson

- Kim Wright

- Lorena Hamer

- Matt Burns

- Maya Paul

- Nick Heath

- Patrick Marshall

- Phillip Nelson

- Richard Opala

- Roberta Stevenson

- Ross Cameron

- Rupert Gale

- Stephen Brown

- Urs Thomas

The PNCIMA initiative also acknowledges the work of Tracey Hooper for her services in editing this document.

The PNCIMA plan was designed by Ion Brand Design, and printed by Hemlock Printers Ltd. Haida artwork included in this plan was created by Tyson Brown. Front and back cover photos by Iain Reid.

1.0 Plan Context

The Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA) is one of five national Large Ocean Management Areas (LOMAs) identified in Canada’s 2005 Oceans Action Plan. The PNCIMA plan is the product of a collaborative process led through an oceans governance agreement between federal, provincial and First Nations Footnote 1 governments and contributed to by a diverse range of organizations, stakeholders and interested parties. The plan is strategic in nature and has been developed pursuant to the 2008 Collaborative Governance Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) among Canada, the Province and First Nations.

1.1 Global Context

In the last century, the ocean has been a new frontier for food sources, transportation, recreation, minerals, energy resources and biotechnology. This trend is expected to continue: growing human populations translate to advances in technology, international movement of products, coastal development and recreation, food production and energy from oceans.

However, development has had its costs. The health of oceans throughout the world is declining along with their ability to produce food, protect against storms, process waste and provide other services that are critical to humans and other life forms (Pew Oceans Commission 2003; U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy 2004; Ban and Alder 2007; Ban et al. 2010).

Three main drivers are believed to affect marine sustainability:

- direct impact of human values and resulting activities in ocean and coastal areas (e.g., unsustainable resource extraction, pollution, urban development and incompatible and crowded ocean uses);

- climate-related impacts (e.g., changing ocean chemistry, temperature and sea levels); and

- limitations of many existing management systems (e.g., divided and duplicated jurisdictions and laws, single sector approaches, limited knowledge, and gaps in responsibility for cumulative effects and overall ocean health) (PNCIMA 2010).

The combination of an increase in ocean use and a decline in ocean health has led to greater interest in sustainable ocean management. Planning for more integrated management of oceans is a pragmatic approach to address these challenges and support opportunities presented by collaboration among ocean users.

Integrated management involves the comprehensive planning and managing of human activities to minimize conflict among users; a collaborative approach that cannot be forced on anyone; and a flexible and transparent planning process that respects existing divisions of constitutional and departmental authority and does not abrogate or derogate from any existing Aboriginal rights or treaty rights (DFO 2002b). Benefits of integrated management planning include:

- reducing cumulative effects of human uses on marine and coastal environments;

- providing increased certainty for the public and private sector regarding existing and new investments; and

- reducing conflict between uses (Minister of Public Works and Government Services 2005).

Additional benefits include:

- integration of data collection and synthesis, monitoring, research, information sharing, communication and education;

- development of inclusive and collaborative oceans governance structures and processes;

- application of flexible and adaptive management techniques to deal with uncertainty and improvements in the understanding of marine species and ecosystems; and

- planning on the basis of natural and economic systems together rather than principally on political or administrative boundaries (DFO 2002b).

Integrated management planning is being implemented at multiple scales by countries and coastal areas in Europe, Australia, Asia and North America. It is informed by international, national and coastal scale processes and sector-based planning initiatives that direct the management of activities.

An important principle that guides integrated management planning is the need to identify ecosystem-based management (EBM) objectives and reference levels to guide the development and implementation of management to achieve sustainable development (DFO 2002b).

1.2 PNCIMA Context

The health of oceans throughout the world is declining along with their ability to produce food, protect against storms, process waste and provide other services that are critical to humans and other life forms.

As in other parts of the world, the PNCIMA ocean environment faces challenges. These challenges, as well as important opportunities, have been identified as driving the need for an integrated management plan in PNCIMA (J.G. Bones Consulting 2009).

Humans have lived in this area for thousands of years, sustained by its abundant marine and terrestrial resources, which also shaped the inhabitants’ social, economic and cultural values. Presently, PNCIMA is home to diverse First Nations, coastal settlements and major communities. The inshore waters of PNCIMA support fishing, aquaculture, marine tourism and transportation. The offshore areas support numerous commercial fisheries and transportation, and the potential for energy developments. The region’s ports are conduits of trade linking Canada‘s businesses to markets in North America, Asia and Europe. The area is ecologically unique for the diversity of ocean features it contains and the important habitat it provides for many species. Increased use of the area exerts increased pressure on ecosystems; therefore, it is important to ensure the coexistence of healthy, fully functioning ecosystems and human communities.

The Great Bear Rainforest (Central and North Coast) and Haida Gwaii are both immediately adjacent and inextricably linked to PNCIMA through collaborative efforts among the federal, provincial and First Nations governments to institute terrestrial ecosystem-based management. These efforts, which have taken place over the past 20 years, have resulted in economic and ecological benefits.

The management and regulation of ocean use in PNCIMA involves a number of First Nations, federal and provincial government departments, local governments and organizations with linked, parallel or overlapping roles and responsibilities that require coordination and harmonization. A summary of federal and provincial legislation and regulations relevant to PNCIMA is provided in Appendix 1. In addition, First Nations have laws, customs and traditions relevant to PNCIMA.

1.3 Plan Scope

The PNCIMA initiative’s aim is to engage all interested and affected parties in the collaborative development and implementation of an integrated management plan to ensure a healthy, safe and prosperous ocean area.

The plan is high level and strategic, and provides direction on and commitment to integrated, ecosystem-based and adaptive management of marine activities and resources in the planning area. Work plans will be developed to support implementation of the plan. The plan focuses on the overall management of PNCIMA by considering ocean uses and the environment. This enables marine planning, management and decision-making to occur at appropriate spatial scales from regional to site-specific. It also promotes the consideration of the interactions among human activities, and between human activities and the ecosystem (DFO 2007a).

The plan presents an ecosystem-based management framework that provides context and direction for ocean management. It contains a set of long-term, overarching goals for ecological integrity, human well-being, collaboration, integrated governance, and improved understanding of the area. These goals are supported by more specific objectives that express desired outcomes and conditions for PNCIMA. The goals and objectives provide the basis for defining management strategies and measuring progress on plan implementation. Above all, the ecosystem-based management framework seeks to ensure that relationships between ecosystem and human use objectives are recognized and reflected in future management decisions.

Together, PNCIMA’s EBM framework, information base (Appendix 2) and decision support tools contribute to the foundation for integrated oceans management in the area, and will support and enable integrated management within other planning, regulatory, decision-making and stewardship processes.

The plan is not intended to provide a detailed prescription of all measures required to achieve its objectives. Instead, it aims to enhance and support existing decision-making processes by linking sector planning and management to an overarching EBM framework. The plan also identifies priorities for action that flow from the EBM framework.

Implementation of the plan is expected to result in greater certainty and stability in oceans management; better integration and coordination of new and existing management and planning processes; sustainable management of resources; and contributions to a national network of marine protected areas (MPAs). However, the plan does not establish a new regulatory framework, restrict existing legislative authorities, fetter ministerial discretion, or fetter or restrict authorities or decisions of the First Nations. Implementation of the plan will take place within existing programs and resources, where possible, and may ultimately lead to the identification of new work which will be implemented as resources permit.

1.4 Governments Working Together: a Foundation for the Plan

Case Study: PNCIMA Collaborative Governance Memorandum of Understanding: an Approach to Integrated Oceans Planning

The arrangement created by the PNCIMA MOU established a governance framework for marine use planning in PNCIMA that engages federal, provincial and First Nations governments. The MOU is an example of a proactive approach to collaborative governance on the west coast of Canada.

The governance model adopted for PNCIMA was designed to support key principles of integrated management, including the recognition of existing authorities and jurisdictions of key parties as well as the need for enhanced communications and coordination between federal, provincial and First Nations governments. The application of the PNCIMA governance framework has enabled some unique outcomes to emerge from the planning process, including:

- the sharing and integration of information and knowledge across the three levels of government and stakeholders to support the development of the plan;

- the achievement of consistency in concepts and outcomes across marine planning initiatives within PNCIMA;

- the establishment of enhanced opportunities for First Nations to collaborate and engage meaningfully in integrated oceans planning;

- the strengthening of relationships between federal, provincial and First Nations governments;

- the opportunity for stakeholders to engage in the development of the marine plan; and

- the identification of information and policy gaps that may require further work and coordination to enable effective implementation of the plan.

Maintaining an ongoing, adaptive governance arrangement will support successful implementation of the PNCIMA plan.

The overlap of jurisdiction and management authority on the sea surface, water column and seabed necessitates a concerted effort by First Nations, federal, provincial and local governments to achieve mutually desired and priority goals for PNCIMA (PNCIMA 2010).

Canada, the Province of British Columbia and First Nations each bring their respective authorities and mandates to the PNCIMA initiative. By respecting these, all parties are able to benefit. The PNCIMA process represents an opportunity to implement a model for integrating broader First Nations interests within ocean-related governance mechanisms (e.g., MPA network planning, proposed Scott Islands Marine National Wildlife Area”, SG̲áan K̲ínghlas – Bowie Seamount Marine Protected Area, Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site).

In 2002, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (then Indian and Northern Affairs Canada) and the Coastal First Nations (then Turning Point Initiative) signed an Interim Measures Agreement to work towards a government-to-government relationship for marine use planning.

In 2004, the Memorandum of Understanding respecting the implementation of Canada’s Oceans Strategy on the Pacific Coast of Canada was signed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada on behalf of the Government of Canada, and by the Ministry of Agriculture on behalf of the Government of British Columbia (DFO 2004). The purpose of the MOU is to promote collaboration between the federal and provincial governments, specifically in the areas of understanding and protecting the marine environment and supporting sustainable economic opportunities.

In 2005, Canada’s Oceans Action Plan identified PNCIMA as one of five priority LOMAs for the implementation of integrated oceans management planning in Canadian waters (DFO 2005).

On December 11, 2008, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, on behalf of the Government of Canada, the Coastal First Nations and the North Coast- Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society, signed the PNCIMA Collaborative Oceans Governance Memorandum of Understanding (DFO et al. 2008). This MOU established a new governance mechanism through which these groups could work together to support the PNCIMA planning process.

In December 2010, the Province of British Columbia signed onto the PNCIMA Collaborative Oceans Governance MOU, effectively changing the 2008 MOU from a bilateral to a trilateral agreement (DFO et al. 2010). In January 2011, the Nanwakolas Council signed onto the MOU (DFO et al. 2011).

In September 2011, Fisheries and Oceans Canada decided to streamline the integrated planning process for PNCIMA. This decision resulted in a reduction in the plan scope and the withdrawal of First Nations from the planning process. Through the period of 10 months of negotiation, the Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative and the North Coast-Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society re-engaged in the process. The Nanwakolas Council withdrew from the process and the collaborative governance MOU. Through negotiation, the remaining parties to the MOU agreed to continue to work together with stakeholders to develop a higher level, more strategic plan.

Legislation and policies are in place to guide integrated oceans management planning in Canada. Following from Canada’s international obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Canada’s Oceans Act came into force in 1997. The Oceans Act calls on the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans to lead and implement integrated management planning for all activities in or affecting estuaries, coastal waters and marine areas, in collaboration with federal, provincial and territorial governments, affected First Nations organizations, coastal communities and stakeholders (Government of Canada 1997). Canada’s Oceans Strategy (DFO 2002a) provides more specific policy direction for implementing the Oceans Act based on the principles of sustainable development, integrated management and the precautionary approach. An accompanying Policy and Operational Framework (DFO 2002b) outlines more specific policy and guidelines for integrated oceans management planning.

Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes and affirms the existing Aboriginal rights and treaty rights of Canada’s Aboriginal peoples. Sections 91 and 92 of the Canadian Constitution Act, 1867 set out the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments. Under section 91, Canada has legislative authority over marine areas, fisheries, Indians and lands reserved for Indians. The federal government also has legislative authority over some matters associated with marine pollution and protection of the environment, although the regulation of matters relating to protection of the environment includes several areas that are within the jurisdiction of the provinces. Under section 92, provincial governments have legislative authority over property and civil rights in the province.

In 1984, in the Strait of Georgia Reference, a dispute between Canada and British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada was asked whether “all of the lands, including the minerals and other natural resources of the seabed and subsoil covered by the waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia (sometimes called the Gulf of Georgia), Johnstone Strait and Queen Charlotte Strait....” were the property of the Province of British Columbia. The Court answered in favour of the Province of British Columbia by finding that, when British Columbia entered Confederation in 1871, the province consisted of all British territories, including those “subject waters and submerged lands...” and “the boundaries of British Columbia has [sic] not changed since that date.”

Various First Nations assert Aboriginal title and rights, including ownership, jurisdiction and management over the lands, waters and resources, including the marine spaces, throughout First Nations Territories in the PNCIMA area.

The importance of First Nations in the governance, stewardship and use of ocean resources is recognized. In addition to those First Nations who are party to the Collaborative Governance MOU, there is a strong commitment to working with other First Nations in the PNCIMA area. PNCIMA is located within numerous First Nations Territories. First Nations have laws, customs and traditions for the protection, management and stewardship of marine areas within PNCIMA. First Nations knowledge, authorities and responsibilities remain vital to ongoing stewardship, management and economic well-being.

Municipalities are established by the provincial legislature, which delegates some of their powers to municipal governments. In British Columbia, the legislature has delegated some authority over land use planning and zoning to local governments.

At the municipal level, bylaws and zoning regulations govern coastal activities of 14 incorporated and 17 unincorporated coastal communities within PNCIMA. Through their work, municipalities and regional districts support socio-economic and ecological systems and contribute to the management of coastal and marine areas through bylaws, zoning and infrastructure planning.

The PNCIMA plan operates within this multijurisdictional context of management and regulation of ocean use in the area and respects existing legal and administrative jurisdictions (DFO 2007a). Regulatory authorities remain responsible and accountable for implementing plan goals, objectives and strategies through management policies and measures within their mandates and jurisdiction.

2.0 Planning Area

“PNCIMA’s ocean area is unique in terms of the diversity of ecosystems it contains and the important habitat it provides for many species.”

PNCIMA encompasses approximately 102,000 km² of marine area and occupies approximately two-thirds of the B.C. coast (Figure 2-1). The boundary of PNCIMA was defined based on a mix of ecological considerations and administrative boundaries. Ecologically, the PNCIMA boundary represents the Northern Shelf Bioregion of the Pacific Ocean. The boundary extends from the base of the continental shelf slope in the west to the coastal watershed in the east (adjacent terrestrial watersheds are not included). North to south, PNCIMA extends from the Canada–U.S. border of Alaska to Brooks Peninsula on northwest Vancouver Island and to Quadra Island in the south (PNCIMA 2011).

An Atlas of the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area, which contains 63 maps showing where human activities occur in PNCIMA and detailing important ecological, hydrological and oceanographic features and communities, was developed by the collaborative governance partners and was completed in 2011 (PNCIMA 2011).

2.1 Marine Environment

The coastline of PNCIMA is characterized by rugged coastal mountains, abundant offshore islands, rocky shores with few sand and gravel beaches, steep valleys and fjords that extend to the ocean floor, and a glacially scoured continental shelf with crosscutting troughs. PNCIMA is located in a transition zone between two areas — the northern area dominated by Alaska Coastal Current downwelling and the southern area by California Current upwelling. PNCIMA’s semi-enclosed basin, varied bottom topography, and freshwater input set it apart from other areas of the North American west coast. Strong tidal mixing in the narrow passes and channels enhances productivity around the periphery (Lucas et al. 2007).

PNCIMA’s ocean area is unique in terms of the diversity of ecosystems it contains and the important habitat it provides for many species (Robinson Consulting 2012). It provides essential spawning and rearing habitat for local salmon populations and is important as a marine migration corridor for more southerly populations (Irvine and Crawford 2011). The region also provides important habitat for ancient colonies of corals and sponge reef communities. The Pacific Region Cold-Water Coral and Sponge Conservation Strategy (DFO 2010) was designed to protect these rare and sensitive components of the marine ecosystem.

Many species of marine mammals occur within PNCIMA for at least part of their life history. For example, three distinct eco-types of killer whales occur in PNCIMA: northern and southern resident killer whales, transient killer whales and offshore killer whales. Sea otters, Steller and California sea lions, northern fur seals, northern elephant seals, harbour seals and leatherback turtles are also found in PNCIMA. In addition, PNCIMA hosts a range of native invertebrates, as well as introduced shellfish and other invertebrate species, two non-indigenous sponges and two non-indigenous species of marine fish.

The marine ecosystem supports a variety of migratory species: stopover migrants, such as marine migratory birds; destination migrants, such as whales; and environmental migrants, such as pelagic zooplankton and fish that enter PNCIMA when water temperatures are unusually warm.

Migrants provide an input of energy and food but also can export energy from the system. Detailed descriptions of the abundant marine species that inhabit the region can be found in the PNCIMA Atlas. The Identification of Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas in the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area: Phase II— Final Report (Clarke and Jamieson 2006) provides additional information on the physical features of the region that produce and support some of PNCIMA’s unique ecological communities.

The Pacific Ocean moderates the climate of PNCIMA, which results in warm, wet winters and cool summers. Very different air pressure patterns in the Gulf of Alaska in summer and winter also produce wet, windy winters and drier, relatively calmer summers. Frequent winter storms with strong southerly winds bring not only high waves but also warmer waters from the south and deep downwelling and mixing of surface waters. Relatively calmer weather in summer with periods of northerly winds brings calmer seas and allows nutrients from deep waters to reach the surface. Intense rainfall along the Coast Mountains in late autumn and winter produces large volumes of freshwater runoff on the eastern side of PNCIMA. Large rivers originating in the B.C. Interior snowfields and glaciers contribute most of the freshwater runoff in other seasons, especially in late spring. Although this summer-winter change in weather is typical in PNCIMA, there have been variations in the weather over past decades, which have affected the area (Irvine and Crawford 2011).

Figure 2-1 Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA)

Additional information

The 2007 Ecosystem Overview: Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA) (Lucas et al. 2007) provides an overview of the physical and biological ecosystems in PNCIMA, including descriptions of physical processes, trophic structure, biomass and habitat in the area.

The 2011 State of the Ocean Report for the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (PNCIMA) (Irvine and Crawford 2011) provides information on the ecology of PNCIMA and insights into changes in this marine ecosystem since publication of the Ecosystem Overview in 2007.

“British Columbia’s north and central coasts are teeming with abundant and diverse marine life, offering a natural wonder in our own backyard.”

Case Study: Management of Unique Species in PNCIMA

There are more than 80 species of cold-water corals in B.C., and 250 species of sponges exist on Canada’s Pacific Coast (Gardner 2009). In 1988, four large glass sponge reefs were discovered in Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound. The reefs are the largest known of their kind in the world: individual reefs measure up to 35 km long, 15 km wide and 25 m high. The reefs have existed in the deep, iceberg-furrowed troughs of Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound for an estimated 9,000 years.

Many cold-water corals and sponges provide structural habitat for a number of fish and invertebrate species that are of economic and social importance to Canadians. For example, live glass sponge reefs provide important nursery habitat for juvenile rockfish, and high-complexity reefs are associated with high species richness and abundance (Cook 2005; Marliave et al. 2009). Protection and conservation of cold-water corals, glass sponge reefs and their associated communities is needed to preserve our natural heritage, protect biodiversity and maintain key ecosystem dynamics.

In B.C. waters, bottom fishing likely has the greatest direct impact on cold-water corals and sponges due to the removal of, or damage to, these organisms. Consequently, DFO, the Groundfish Trawl Advisory Committee and the Canadian Groundfish Research and Conservation Society have worked together to prohibit commercial and research groundfish trawl activity within the footprint of the Hecate Strait glass sponge reefs since 2002. In 2006, the original closure boundaries were extended, and the closure was expanded to include shrimp trawl fishing in order to provide greater protection for the reefs. In 2010, to enhance protection and prevent impacts by all human activities in perpetuity, the glass sponge reefs were identified as an Area of Interest for designation as a marine protected area under the Oceans Act. Today, work is continuing to establish the Area of Interest as an Oceans Act marine protected area and scientific research is being conducted to better understand these unique and vulnerable species.

2.2 Human Use

The information contained in this section may not fully reflect the views of Canada, the Province or First Nations.

"People have lived in this area for thousands of years, sustained by its abundant marine and terrestrial resources, which also shaped the inhabitants’ social, economic and cultural values."

Summary of Current Marine Activities in PNCIMA

First Nations marine resource use: Harvest of marine resources by First Nations

Sport fisheries: Recreational angling, collecting of shellfish, harvesting of finfish and invertebrates by residents and visitors for personal use

Commercial fisheries: Harvest of wild finfish and invertebrates for commercial purposes

Aquaculture: Culture of finfish, shellfish or plants in the aquatic environment or manufactured container

Seafood processing: Transformation of wild and cultured seafood into food products for sales to domestic and international markets

Ocean recreation/tourism: Cruise ship tourism, recreational boating, paddle sports, including kayaking, whale watching and diving by residents and visitors

Marine transportation: All vessels greater than 20m, beginning/ending voyage in PNCIMA or in transit; small vessel movement undocumented

Marine energy and mining: Existing and potential energy and mineral resources

Tenure on aquatic lands: Granting of tenure on land below the high water line; tenure is often ancillary to primary activity, such as aquaculture, log storage and moorage

Ocean disposal: Deliberate disposal of approved substances at approved marine sites

National defence and public safety: Activities countering threats to security and sovereignty, and resources used to address public safety

Research, monitoring and enforcement: Efforts to learn more about marine functions for better management, supported by monitoring and enforcement; compliance with policy and regulations

The marine ecosystems within PNCIMA provide important habitat for many species and marine resources that contribute to coastal economies and communities. People have lived in this area for thousands of years, sustained by its abundant marine and terrestrial resources, which also continue to shape the inhabitants’ social, economic and cultural values (Robinson Consulting 2012).

British Columbia is a major gateway for Asian trade to and from North America. All three major PNCIMA ports – Stewart, Kitimat and Prince Rupert – are poised for expansion to facilitate increased trade with Asian markets (GSGislason & Associates Ltd. 2007).

B.C. businesses that depend on the ocean environment include resource extraction, processing and distribution (e.g., seafood processing); goods construction and manufacturing (e.g., ship building); and services (e.g., ocean transportation and ocean-based recreation). In addition, public (government) and non-government sector activities are tied to the promotion and regulation of ocean-based business activities, ocean-related education and research, and ocean environmental stewardship.

Overall, the ocean sector makes an important contribution to the B.C. economy. Direct revenues from B.C. ocean sectors exceeded $11 billion Footnote 2 in 2005, and the total ocean sector impacts comprised 7-8% of the B.C. economy. Precise economic numbers are not available for the PNCIMA region.

There is substantial potential for growth within the B.C. ocean economy, both from existing sectors and from potential new energy sectors (GSGislason & Associates Ltd. 2007).

First Nations cultures and communities within PNCIMA are inextricably tied to the marine environment. For thousands of years, First Nations have used marine resources for a wide variety of purposes. Traditional activities include the management, harvesting (including seasonal and rotational harvest), preparation, consumption and exchange of marine resources, which occur year-round. First Nations consider that marine resources play a unique role in shaping and characterizing the identity of the people who rely on them (Garibaldi and Turner 2004).

A variety of gears and methods, including traditional systems of resource use and modern gear, is used to harvest species for families, communities and commercial purposes. Knowledge is passed down from generation to generation, including where, how and when to access food resources, as well as how to process and preserve food throughout the year. Traditional knowledge of natural features, animal behaviour and ocean conditions is often used, and it is an important source of information for documenting changes in marine environments over time (PNCIMA 2011; Robinson Consulting 2012). First Nations advise that their marine governance and resource management systems include such things as harvest technologies, spatial and social restrictions, seasonal avoidance, selective harvesting, stock management and transplantation, and habitat management and enhancement, and that these systems controlled harvest levels and allowed for the sustainable use of a broad variety of marine resources for millennia (McDonald 1991, 2003; Jones and Williams-Davidson 2000; Turner 2003; Menzies and Butler 2007, 2008; Menzies 2010; Mitchell and Donald 2001).

First Nations integrated the industrial fishery into their economies and contributed significantly to the development of the B.C. fishery. They continue to value and prioritize participation in this industry. First Nations have actively participated in growing marine industries, such as commercial fishing, hunting and boat building. Their access to marine resources requires considerable travel within and between territories, using travel routes that have been developed for efficiency and safety. First Nations view marine transportation routes – including those for canoe, fish boats and other vessels – as important ways to travel between their coastal communities.

They continue to rely on trading relationships among coastal First Nations and with Interior communities to provide access to a broader range of marine and terrestrial species (Turner 2003; Menzies 2010). First Nations seek to ensure an ongoing sustainable relationship with marine resources, strengthened by such things as cooperative food gathering and a responsibility to maintain and protect important and sensitive marine ecosystems. They consider their historic and ongoing relationships with the ocean and marine resources to be critical foundations of their food, social, cultural and economic laws, custom, practices and traditions, including governance and management.

Non-First Nations settlement in PNCIMA is less than 200 years old. The growth and development of many of the earliest settlements was based on a number of factors, including alliances with First Nations and access to seafood. Fishing boats quickly became an essential element in participating in fish harvesting and other resource activities such as forestry and beachcombing. The ability to move or switch to other resource activities through the year allowed coastal villages to remain relatively stable.

Hunting, fishing, and plant gathering also supported coastal communities. Local boat building was widespread in both First Nations and non-First Nations communities and offset the need for capital and the importation of manufactured goods. Reliance on this local industry forged relationships and networks among family groups and villages, and allowed the communication and transfer of local and technical knowledge. Networks and the development of formal and informal organizations contributed to the distribution of credit, commodities, labour, recreation and cultural activities.

Early market economies in British Columbia were based on ocean-related industries, such as canoe and ship building, fishing and coastal logging. Over the years, the growth of exportoriented sectors, from mining and forest products to agricultural goods and petroleum production, depended on ocean transportation for access to markets. Now, emerging industries like ocean tourism and marine technology development are helping drive the economy (GSGislason & Associates Ltd. 2007).

Today, the lands adjacent to PNCIMA support 14 incorporated, 18 unincorporated and 32 First Nations communities (Table 2-1). The coastline of PNCIMA is shared among five regional districts: Kitimat-Stikine, Skeena-Queen Charlotte, Central Coast, Mount Waddington, and Strathcona. The communities and regional districts in PNCIMA are mapped in Appendix 4. These communities support both terrestrial and marine activities, although the scope of the PNCIMA plan is limited to the marine environment and its associated use. Footnote 3

The population estimate for the incorporated and unincorporated communities in Table 2-1 for 2011 was 118,416 (BC Stats 2011). This estimate does not include the listed First Nations communities. From 1975 to 2009, the population declined in all regional districts in PNCIMA except Strathcona. As a result of growth in the Strathcona Regional District, the total PNCIMA population grew about 9% over that period, whereas the total provincial population increased by almost 75%. The issue of declining populations and loss of a local tax base associated with the decline in the region‘s resource sectors has created new challenges for communities within PNCIMA. A provincial index of socio-economic well-being suggests that communities in PNCIMA face a relatively higher level of socio-economic hardship than communities elsewhere in B.C. (Robinson Consulting 2012).

The Socio-Economic and Cultural Overview and Assessment Report for the Pacific North Coast Integrated Management Area (Robinson Consulting 2012) provides a summary and synthesis of information on socio-economic and cultural values and issues, including profiles of the status, trends and outlook of coastal communities bordering the planning area, the role of the marine environment in shaping the region‘s cultural values, and the ocean’s contribution to selected economic activities.

| Incorporated Communities | Unincorporated Communities | First Nations Communities |

|---|---|---|

| Kitimat-Stikine Regional District | ||

|

|

|

| Skeena-Queen Charlotte Regional District | ||

|

|

|

| Central Coast Regional District | ||

|

|

|

| Mount Waddington Regional District | ||

|

|

|

| Strathcona Regional District | ||

|

|

|

2.3 Future of the Planning Area

The future of PNCIMA’s marine environment is subject to much uncertainty. Satellite observations since 1993 indicate global sea levels are rising at a rate of 30 cm per century. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicted sea levels will rise by 20–60 cm over the 21st century, but recent observations of ice melt in Greenland and Antarctica suggest these projections might be too low. Therefore, greater rates of sea level rise in British Columbia can be expected in the future. With long-term global warming, even higher rates of sea level rise are expected after 2100. Recent studies of global predictions of sea level rise and local effects in British Columbia have suggested that sea level rise at Prince Rupert in the 21st century might be 20–30 cm (Irvine and Crawford 2012).

Climate change is also likely to cause changes in both biological productivity and runoff patterns in PNCIMA. The productivity of the marine ecosystem as a whole is influenced by the extent of upwelling and favourable winds. If these winds change as a result of natural climate changes, as has happened in the past, they will have an impact on the productivity of the entire ecosystem. The spatial pattern of plankton productivity will be affected by changes in the hydrological regime. If the timing or amount of freshwater runoff changes, the degree of nutrient entrainment into the upper layers of the water column by estuarine processes and the locations at which these processes occur could be affected.

Another important global trend is the increasing acidification of the oceans due to increases in carbon dioxide concentration in ocean waters. This presents a threat to organisms that produce calcite and aragonite shells or structures, such as pteropods, corals and bivalves. The full impacts of increasing acidity are not known. Most of this additional carbon dioxide is derived from human activities (Lucas et al. 2007).

BC Stats (2011) forecasts PNCIMA’s population will grow by 8,800 residents between 2009 and 2036 – an increase of just over 7% compared to a 36% forecasted increase in the provincial population. The forecasted growth is expected to be concentrated in the Strathcona Regional District area of PNCIMA.

First Nations rely on fisheries and marine resources for food, social, ceremonial and commercial purposes. There have been declines in various species, including abalone, eulachon, inshore rockfish and some salmon stocks, which are species that First Nations have relied on and will continue to do so.

Many communities in PNCIMA have infrastructure deficits that will require considerable investment in the future. Many communities have also experienced a decline in commercial fishing, and they are further challenged in positioning their communities in new economies (Robinson Consulting 2012). More specific information about the future of key marine activities within the region is provided in Appendix 3.

3.0 The Planning Process

3.1 Governance Arrangements

Under the PNCIMA Collaborative Governance MOU, First Nations, Footnote 4 federal and provincial government staff worked together in a Steering Committee that provided strategic direction and executive oversight to the PNCIMA initiative. First Nations, federal and provincial technical staff worked together in a Planning Office which supported the Steering Committee and the Integrated Oceans Advisory Committee. Advice from stakeholders was formally provided by the Integrated Oceans Advisory Committee, which is described in further detail in Section 3.2.

All organizations and individuals who engaged in different components of the PNCIMA process are identified in Appendix 5. The PNCIMA process structure is outlined in Figure 3-1.

First Nations party to the Collaborative Governance MOU coordinated their participation in the PNCIMA Steering Committee through a First Nations Governance Committee consisting of First Nations leaders from Haida Gwaii, the North Coast and the Central Coast, with technical support at the PNCIMA Planning Office from several organizations, including the Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative, North Coast- Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society, Haida Fisheries Program, and the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance. The Regional Committee on Oceans Management informed and coordinated federal and provincial agencies’ participation in the Steering Committee and in the Planning Office. Appendix 5 provides a list of participants on these committees.

Governance mechanisms are expected to evolve as relationships and experience continue to develop. In addition, the federal and provincial governments are committed under the PNCIMA Collaborative Governance MOU to engage and consult with First Nations that are not currently signatories to the PNCIMA Collaborative Governance MOU.

3.2 Engagement of Interested Parties

Stakeholder participation was critical to the development of the PNCIMA plan. A detailed description of the engagement approach is provided in the PNCIMA Initiative Engagement Strategy (PNCIMA 2010c). To achieve effective participation, a variety of tools and mechanisms were developed to encourage ongoing engagement and to document the views and knowledge of stakeholders, communities and the general public. These tools and mechanisms are outlined in Figure 3-2. A list of public forums and meetings that were held is provided in Appendix 6.

The PNCIMA Integrated Oceans Advisory Committee (IOAC) was a central component of the PNCIMA planning process and was essential in facilitating ongoing engagement with stakeholders as the process evolved. The IOAC was established as a multi-sector advisory body to provide guidance on the planning process, its outputs and the implementation of the integrated management plan. The IOAC consisted of participants from industry, regional districts, recreational groups, environmental non-governmental organizations and other interested parties. First Nations and federal and provincial governments participated as ex-officio members in order to provide feedback on IOAC discussions. Appendix 5 provides a list of the IOAC membership.

The PNCIMA Steering Committee considered the role of the IOAC to be important in developing the integrated management plan. Throughout the planning process, advice and recommendations from the IOAC were shared with the PNCIMA Steering Committee. Outcomes of the Steering Committee review were shared with the IOAC, which provided an opportunity to resolve differences by consensus, thereby allowing for broad support across participating sectors and interests. Following changes to the planning process in September 2011, as referenced in Section 1.4, engagement with the IOAC changed from a consensus-seeking approach to a more consultative approach. Consequently, the IOAC reached consensus on some but not all elements of the plan. The role of the IOAC is advisory in nature only. Therefore, the plan will not limit or prejudice the positions of the IOAC members in the future.

3.3 Development of the Plan

The PNCIMA planning process, outlined in Figure 3-3, was comprised of many stages, over many years. Once the collaborative planning process was developed and existing information was assembled and assessed, parties began working on developing an EBM framework for PNCIMA.

The framework was jointly developed over the course of 2010, 2011 and 2012 by collaborative governance partners and the IOAC. First, the parties developed a definition of EBM for PNCIMA. Second, assumptions, principles, goals and objectives for the area were formulated. Then strategies that support the overall goals and objectives for PNCIMA were identified. It is important to note the scale and complexities associated with implementing all aspects of each strategy. In order to address this, a number of priorities were identified for short-term implementation.

Management and decision support tools for identifying management issues in PNCIMA were developed concurrently with the EBM framework. In 2012, DFO developed a pilot ecological risk assessment framework to assist with identifying ecological components at greatest risk from human activities (DFO 2012a). This tool continues to be developed and refined. The lack of a decision support tool related to socio-economic and cultural activities in PNCIMA has been identified as a significant gap. Ongoing work on cumulative effects assessment throughout the province has indicated that a collaboratively developed assessment tool or framework would also be useful for PNCIMA.

Together, PNCIMA’s EBM framework, information base and decision support tools form the foundation for integrated ocean management in the area, and will support and enable integrated management within other planning, regulatory and decision-making processes.

3.4 Related Marine Planning Processes

While the PNCIMA process has focused on developing a strategic level plan for the area, many other marine-based planning processes are under way at various scales both within and adjacent to PNCIMA. The intended role of the PNCIMA plan is to provide an overarching marine EBM framework that is available to guide marine planning and management at these other scales.

A variety of land use plans provide direction on the use and allocation of resources in coastal B.C. Participants in these planning processes recognized that upland activities could have a major bearing on the marine environment, and agreed that more comprehensive integrated marine use planning should be undertaken following completion of regional land use plans. Furthermore, a number of the resulting land use agreements led to the designation of coastal protected areas (which include the marine environment), which require complementary nearshore and foreshore marine planning. Land use plans for areas adjacent to the PNCIMA planning area include the Central Coast and North Coast Land and Resource Management Plans (Coast Land Use Decision), Council of the Haida Nation/B.C. protected area management plans on Haida Gwaii, and the Vancouver Island Regional Land Use Plan. The Nisga’a Final Agreement defines the rights of the Nisga’a Nation with respect to marine and freshwater resources in the Nass area at the northern extent of the planning area.

Marine use plans exist at different scales within the PNCIMA boundary, and include the Johnston Strait-Bute Inlet Coastal Plan, Quatsino Sound Coastal Plan, and North Island Straits Coastal Plan. In addition, the Marine Plan Partnership for the North Pacific Coast (MaPP), a partnership between the Province of British Columbia, Coastal First Nations – Great Bear Initiative, North Coast–Skeena First Nations Stewardship Society and Nanwakolas Council, has developed a Regional Action Framework and sub-regional coastal and marine plans for the North Coast, the Central Coast, North Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii. The federal government was not involved in the MaPP planning process. The MaPP initiative shares the same footprint as PNCIMA and draws from, and builds on, the PNCIMA plan. For example, MaPP adopted the EBM framework established through the PNCIMA initiative. MaPP partners worked with stakeholders and the public to develop strategies and spatial plans that will inform the development, use and protection of marine spaces throughout the area.

A number of the First Nations have developed plans and management tools at multiple scales. These include community, sub-regional and regional integrated marine use plans comprised of goals, objectives, strategies, collaborative government relationships, spatial management and various partnerships with stakeholders.

The PNCIMA planning process also has linkages to a number of marine protected areas. Planning within the Gwaii Haanas National Marine Conservation Area Reserve and Haida Heritage Site will help achieve some of the goals and objectives outlined within this PNCIMA plan. Information gathered by Parks Canada and the Council of the Haida Nation was available to the PNCIMA initiative throughout the plan’s development. Similarly, Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Canadian Wildlife Service is leading an initiative to establish a National Wildlife Area in the marine waters surrounding the Scott Islands off the northwestern tip of Vancouver Island. This proposed protected marine area would conserve the marine foraging habitat of the largest seabird colony in British Columbia as well as conserve the marine habitats for other wildlife that uses the area. DFO has also proposed that the Hecate Strait/Queen Charlotte Sound glass sponge reefs be designated as a candidate marine protected area, which would provide comprehensive and long-term management and protection for this unique area. In 1997 the CHN designated SG̲áan K̲ínghlas as a Haida marine protected area. In 2008 DFO designated Bowie Seamount as a Marine Protected Area (MPA) under Canada’s Oceans Act. Respecting the collaborative approach to the area’s planning and management, it is commonly referred to as the SG̲áan K̲ínghlas – Bowie Seamount (SK̲-B) MPA. Although the area is outside the PNCIMA boundary, there are ecological linkages to PNCIMA.

Additionally, the Province of British Columbia has been working with First Nations in the Haida Gwaii and the Central and North Coast planning regions to identify areas for conservancy/protected area establishment, which includes protection of the marine foreshore. In addition to protecting biodiversity and recreation values, conservancies/ protected areas expressly recognize the importance of some natural areas to First Nations for food, social, ceremonial and cultural uses. Marine foreshore areas for the conservancies/ protected areas in the Haida Gwaii and North Coast planning regions were identified and established through broader strategic land use planning processes that also provide certainty for users and support sustainable economic opportunities for coastal communities. The conservancies/protected areas protect a high diversity of marine landscapes and habitats, including productive estuarine complexes, sea grass meadows, kelp forests and internationally significant seabird nesting colonies. Their selection was based in part on an analysis of ecosystem representation and special feature conservation. In the Central Coast planning region, the Province of British Columbia and First Nations are using management planning processes to identify marine foreshore areas that can be added to coastal conservancies. Detailed values, aspirations and uses for each conservancy are being considered and incorporated into individual protected area management plans.

In addition to these multi-user planning processes, it will be important to consider sector-specific planning and management at various scales during implementation of the PNCIMA plan. DFO develops Integrated Fisheries Management Plans to manage the fishery of a particular species in a given region. These plans combine the best available science on a species with industry data on capacity and methods for harvesting that species. Internationally, Canada is a member of the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission. Additionally, the Pacific Salmon Treaty, signed by Canada and the United States in 1985, provides the framework in which the two countries work together to conserve and manage Pacific salmon.

The Canadian Marine Advisory Council is Transport Canada’s national consultative body for marine matters. Participants include individuals and representatives of parties that have a recognized interest in boating and shipping. The Council addresses concerns regarding safety, recreational matters, navigation, marine pollution and response, and marine security. Internationally, Canada is a member of the International Maritime Organization, whose mission statement is “Safe, secure and efficient shipping on clean oceans” (IMO 2011). There are also ongoing tripartite discussions between the federal government, provincial government and First Nations regarding shipping and transportation issues and related planning.

4.0 Ecosystem-Based Management Framework

Ecosystem-based management is an adaptive approach to managing human activities that seeks to ensure the coexistence of healthy, fully functioning ecosystems and human communities. The intent is to maintain those spatial and temporal characteristics of ecosystems such that component species and ecological processes can be sustained and human well-being supported and improved. Footnote 5

Understanding of EBM in B.C. has evolved in recent years. The concept was used in relation to land use planning as part of the implementation of the 2001 Central Coast Land and Coastal Resource Management Planning Phase I Framework Agreement. Through this process, the Province of British Columbia, First Nations from the Central and North Coasts and Haida Gwaii, local governments and non-government interests reached consensus on establishing a definition, principles and goals for EBM. Parties to the agreement made a commitment to implement EBM in coastal B.C. as a means of achieving “healthy, fully functioning ecosystems and human communities”.

Canada’s 2002 Policy and Operational Framework for Integrated Management of Estuarine, Coastal and Marine Environments places equal importance on EBM. It identifies EBM as a fundamental principle by which integrated management should be guided, and states that the identification of EBM objectives and reference levels will guide the development and implementation of management in order to achieve sustainable development.

EBM, although not a term used historically by First Nations, has been their way of practicing stewardship for thousands of years, using a number of similar principles such as “interconnectedness,” “sharing,” “balance,” “learning” and honouring the Creator/creation, as taught by their ancestors.

Through the PNCIMA initiative, many of the same parties involved in the land use planning process, and others with interests in the marine environment, came together again to define EBM for marine ecosystems. The result of this collaboration was an EBM framework that is the central feature of the PNCIMA plan. Figure 4-1 depicts the various components of the EBM framework for PNCIMA. The uppermost components (definition, assumptions and principles) provide broad guidance to the plan. Components that are in the middle of the framework (goals, objectives, strategies) are more specific statements that are based on an understanding of key issues and are identified through various analyses. The lower components of the diagram illustrate an adaptive management cycle in which strategies are adapted based on monitoring and evaluating the results of implementation.

Case Study: First Nations Culture, the Marine Environment and Ecosystem-Based Management

Respect for the land, sea, spirit world and all living things is at the heart of First Nations interactions with nature. Coastal First Nations have been practising ecosystem-based management of the land and sea for countless generations. The understanding that humans are part of the ecosystem, a concept that is reflected in EBM principles, is integral to First Nations values, beliefs and approaches to land and marine stewardship (Jones et al. 2010). The understanding that “everything depends on everything else” is also the basis for all First Nations marine use plans. For example, from the Haida perspective:

Haida culture is intertwined with all of creation in the land, sea, air and spirit worlds. Life in the sea around us is the essence of our well-being, and so our communities and culture. We know that our culture depends on the sea around us, and that the well-being of every community and Nation is at risk. It is imperative that we bring industrial marine resource use into balance with, and respect for, the well-being of life in the sea around us.

EBM provides the foundation for addressing many marine issues that are being discussed at community-based, sub-regional and regional marine use planning tables. These issues include fisheries sustainability, conservation, habitat protection, marine-based economic development, and monitoring and enforcement. Through joint planning processes, the provincial and federal governments and First Nations developed a set of EBM principles and goals that promote marine ecosystem health and restoration alongside social, cultural and economic well-being. These EBM principles and goals will help guide marine use management at multiple scales and across many marine activities in PNCIMA.

4.1 EBM Assumptions and Principles for PNCIMA

Assumptions

- Ecosystem goods and services underlie and support human societies and economies; such goods and services can be direct or indirect.

- Humans and their communities are part of ecosystems, and they derive social, cultural and economic value from marine ecosystem goods and services.

- Human activities have many direct and indirect effects on marine ecosystems.

- EBM informs the management of human activities.

- Marine ecosystems exist on multiple spatial and temporal scales, and are interconnected.

- Marine ecosystems are dynamic and subject to ongoing and sometimes unpredictable change.

- Marine ecosystem states have limits to their capacity to absorb and recover from impacts.

- Human understanding of marine ecosystems is limited.

- Humans prefer some ecosystem states more than others.

- Humans can manage some drivers of change better than others, and can adjust or respond to some changes better at the scale of PNCIMA planning.

Principles

- The EBM approach seeks to ensure ecological integrity. It seeks to sustain biological richness and services provided by natural ecosystems, at all scales through time. Within an EBM approach, human activities respect biological thresholds, historical levels of native biodiversity are met, and ecosystems are more resilient to stresses and change over the long term.

- The EBM approach includes human well-being. It accounts for social and economic values and drivers, assesses risks and opportunities for communities, and enables and facilitates local involvement in sustainable community economic development. An EBM approach aims to stimulate the social and economic health of the communities that depend on and are part of marine ecosystems, and it aims to sustain cultures, communities and economies over the long term within the context of healthy ecosystems.

- The EBM approach is precautionary. It errs on the side of caution in its approach to management of human activity and places the burden of proof on the activity to confirm that management is meeting designated objectives and targets. Uncertainty is recognized and accounted for in the EBM approach.

- The EBM approach is adaptive and responsive in its approach to the management of human activities. It includes mechanisms for assessing the effectiveness of management measures and changing such measures as necessary to fit local conditions.

- The EBM approach includes the assessment of cumulative effects of human activities on an entire ecosystem, not just components of the ecosystem or single sector activity.

- The EBM approach is equitable, collaborative, inclusive and participatory. It seeks to be fair, flexible and transparent, and strives for meaningful inclusion of all groups in an integrated and participatory process. EBM is respectful of federal, provincial, First Nations and local government governance and authorities, and recognizes the value of shared responsibility and shared accountability. It acknowledges cultural and economic connections of local communities to marine ecosystems.

- The EBM approach respects Aboriginal rights, Aboriginal titles and treaty rights, and supports working with First Nations to achieve mutually acceptable resource planning, stewardship and management.

- The EBM approach is area-based. Management measures are amenable to the area in which they are applied; they are implemented at the temporal or spatial scales required to address the issue and according to ecological rather than political boundaries.

- The EBM approach is integrated. Management decisions are informed by consideration of interrelationships, information, trends, plans, policies and programs, as well as local, regional, national or global objectives and drivers. The EBM approach recognizes that human activities occur within the context of nested and interconnected social and ecological systems. As such, EBM concurrently manages human activities based on their interactions with socialecological systems. The approach helps to direct implementation of measures across sectors to integrate with existing and, where agreed, new management and regulatory processes.

- The EBM approach is based on science and on wise counsel. It aims to integrate the best available scientific knowledge and information with traditional, intergenerational and local knowledge of ecological and social systems and adapt it as required.

4.2 Goals, Objectives and Strategies for PNCIMA

PNCIMA’S EBM goals are interconnected and cannot be taken as separate from one another. It is the purpose of the PNCIMA EBM Framework to achieve:

- integrity of the marine ecosystems in PNCIMA, primarily with respect to their structure, function and resilience

- human well-being supported through societal, economic, spiritual and cultural connections to marine ecosystems in PNCIMA

- collaborative, effective, transparent and integrated governance, management and public engagement

- improved understanding of complex marine ecosystems and changing marine environments

The EBM objectives for PNCIMA, as outlined in Table 4-1, were developed through a collective effort. The IOAC carefully considered how to best reach the PNCIMA goals, and worked to develop EBM objectives which were subsequently reviewed by all collaborative governance parties. The objectives that appear in the plan reflect the recommendations made by the IOAC, as well as input from the PNCIMA Steering Committee. They are applicable to PNCIMA as a whole but can be equally applied to planning, management and decision-making at other spatial scales within the area. As with the goals, these objectives are interconnected.

Management strategies and associated timelines for advancing PNCIMA objectives are outlined in Table 4-1. Strategies may influence the outcome of more than one objective; therefore, some duplication is present. Specific actions are not identified in the EBM framework. They will be identified on a case-by-case basis through work planning as particular strategies are implemented.

Strategies relate to the authorities and priorities of various departments, agencies and organizations. They are not meant to be implemented in isolation or by a single department, agency, organization or individual. Rather, they are meant to integrate EBM into the regular course of business for all governments, First Nations and stakeholders involved in PNCIMA. Therefore, responsibility for implementing particular strategies is shared among all parties to the PNCIMA initiative.

Defining goals, objectives, and strategies

Goals relate to the broad purpose and expected end result of the planning initiative, and apply to the whole plan area. They reflect broad ideals, aspirations or benefits pertaining to specific environmental, economic or social issues, and are the general ends towards which efforts are directed. Goals answer the question, “What must be accomplished to realize what we want?” They are achieved through objectives, strategies and actions.

Objectives also describe a desired future state but are more specific and concrete than goals. They are the means of reaching the goals. They answer the question, “What steps are required to achieve the goal?”

Whereas objectives define “what” outcome is intended for particular resource values, strategies describe “how” the desired outcome will be achieved. They answer the question, “What measures or actions are required to make progress towards achieving the goals and objectives?”, and they correspond directly to the objective they serve.

Table 4-1 Goals, objectives and strategies for PNCIMA

| Objective Footnote 6 | Strategy | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Conserve the diversity of species, viable populations and ecological communities and their ability to adapt to changing environments. | 1.1.1 Update and enhance understanding and knowledge of ecological communities. | Ongoing |

| 1.1.2 Update and enhance work to identify and characterize risks to species diversity, population viability and ecological communities. | Ongoing | |

| 1.1.3 Update and enhance existing spatial and analytical information on species diversity, population viability and ecological communities. | Long term | |

| 1.1.4 Assess existing management measures for their ability to conserve species diversity, population viability and ecological communities. | Short term | |

| 1.1.5 Identify, assess and adapt possible management measures to address conservation of species diversity, population viability and ecological communities. | Short term | |