Canada's Policy for Conservation of Wild Atlantic Salmon

Fisheries & Oceans Canada

August 2009

THE WILD ATLANTIC SALMON CONSERVATION POLICY – A SNAPSHOT

- The Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy is intended to transform the approach to conserving Atlantic salmon, their habitat, and dependent ecosystems. Key elements of the policy recognize that:

- Protection of the genetic and geographic diversity of salmon is necessary for their future evolutionary adaptation and long-term well-being.

- Shared stewardship in conjunction with carrying out mandated responsibilities provides the most efficient and effective use of resources to achieve conservation objectives. Resource management decision making has to be shared and undertaken using open and accountable public processes that are collaborative, inclusive and comprehensive.

- Future success in salmon conservation relies on use of freshwater, estuarine and marine habitats; the policy needs to address challenges in all three habitats. Habitat requires effective protection and rehabilitation if salmon are to prosper. Such actions require partnered approaches with provinces and others.

- Ecosystems must be considered in management decision making to foster the conservation of salmon in an increasingly uncertain future.

- Management must be based on good scientific information and consider biological, social, and economic consequences.

- The goal of the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy is to maintain and restore healthy and diverse salmon populations and their habitats for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of Canada in perpetuity.

- This goal will be guided by four principles:

- Conservation. Conservation of wild Atlantic salmon, their genetic diversity and their habitats is the highest priority in resource management decision making.

- Sustainable Use and Benefits. Resource management decisions will consider biological, social, and economic consequences; reflect best science including Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge and local knowledge, and maintain the potential for future generations to meet their needs and aspirations.

- Open and Transparent Decision Making. Resource management decisions will be made in an open, transparent and inclusive manner.

- Shared Stewardship. Conservation initiatives will be optimised by actively engaging provincial governments, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations and other stakeholders in the development, implementation, promotion, maintenance of, and compliance with management decisions, and by the sharing of responsibility and accountability for the outcome of such decisions. Nevertheless, DFO will maintain its legislative authority towards the conservation of Atlantic salmon and its habitat.

- Wild salmon will be conserved by managing populations in "Salmon Management Areas" (SMAs ).

- The status of SMAs will be evaluated through monitoring programs in index rivers and assessed against selected benchmarks, and reported publicly.

- Habitat protection and management for wild Atlantic salmon will focus on an integrated approach involving assessment of habitat condition, identification of indicators and benchmarks, and monitoring of status.

- Ecosystem considerations will be incorporated into salmon management, particularly in relation to marine survival.

- The policy aims to maintain and improve Atlantic salmon diversity through the protection of SMA populations but recognizes there will be exceptional circumstances where it is neither feasible nor reasonable to fully address all risks. Where an assessment concludes that conservation measures will be ineffective or the social or economic costs to rebuild a population(s) within an SMA would be unacceptably high, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans may decide to limit the range of measures taken.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

THE WILD ATLANTIC SALMON CONSERVATION POLICY – A SNAPSHOT

- Wild Atlantic Salmon – a Renewed Management Approach

- Legal Context for the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy

- Atlantic Salmon and Diversity

- The Importance of Habitat and Ecosystems

- Salmon Diversity and Biodiversity

POLICY FOR THE CONSERVATION OF WILD ATLANTIC SALMON

- GOAL AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES

- OBJECTIVES

- STRATEGIES AND ACTION STEPS

- STRATEGY 1: ASSESSMENT AND MONITORING OF POPULATION STliiliiTUS

- STRATEGY 2: CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION OF ATLANTIC SALMON HABITAT

- STRATEGY 3: INCLUSION OF ECOSYSTEM VALUES AND MONITORING

- STRATEGY 4: INTEGRATED FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PLANNING

- STRATEGY 5: PROGRAM DELIVERY

- STRATEGY 6: PERFORMANCE REVIEW

IMPLEMENTATION – ‘MAKING IT ALL WORK’

APPENDIX 1: LEGAL AND POLICY BACKGROUND

INTRODUCTION

What are Wild Atlantic Salmon?

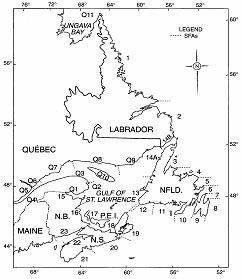

The Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy addresses the anadromous (sea-run) form of (Salmo salar L.). The landlocked form of S. salar, variously known as landlocked, ouananiche or Sebago salmon, is omitted in large part from this policy because its management has been divested to the provinces. The sea-run form frequents coastal rivers and streams of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, and in Québec, Ungava and the North and South shores of the St. Lawrence River.[1]

Salmon are considered “wild” if they have spent their entire life cycle in the wild and originate from parents that were also produced by natural spawning and continuously lived in the wild. In situations where Atlantic Salmon stocks are being recovered through a live gene banking process (protection of genetic diversity) to reestablish populations, that are listed or at risk of extirpation, the progeny of these facilities are considered “wild” salmon.

[1] Wild Atlantic salmon re-introduced into rivers and streams of Lake Ontario are considered landlocked and are not included in this policy.

In “The Atlantic salmon in the history of North America”, R.W. DunfieldFootnote 1 summarized that for a thousand years the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) has occupied a salient position in the history of eastern North America. Originally a food source for Aboriginal people, it became “an increasingly important factor in both the domestic and commercial life of the developing colonies” where it “provided a recreational outlet for sportsmen and evolved as a principal object of intellectual and scientific investigations”. Dunfield noted that the “documented specifics of the salmon’s history, however, are largely comprised of repetitive instances of overexploitation, careless destruction of stocks and their environment, ineffective conservation actions”, and more recently, “a declining presence”. He concluded that its destiny appears to be extinction.

Since the inauguration of the last policy for Atlantic salmonFootnote 2 in 1986, Department efforts to arrest the decline have been persistent, expensive, and consistently challenged by new or emerging threats to their survival. Efforts to arrest the down turn have included the termination of all commercial fisheries, reduction and in some areas suspension of recreational salmon fishing, new legislation for fish passage and habitat protection, improved scientific advice to regulate and close fisheries, and supplementation of stocks through fish culture practices. New challenges are associated with Supreme Court decisions, poor marine survival, extirpation of populations, habitat degradation and loss, reviews of government program priorities and activities, international agreements and new Canadian legislation governing species at riskFootnote 3 and, in some areas, poor compliance with management measures. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) has always adapted to changing circumstances and its priorities will continue to be reshaped to address these contemporary challenges and secure a turn around in the fate of Canada’s wild Atlantic salmon.

This “Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy” represents Canada’s commitment and planned course of action for the conservation of wild Atlantic salmon. As such, the policy will provide guidance for the development of a strategic and integrated implementation plan to address current challenges. The policy is in keeping with a mandate to develop a common vision for the future management of wild Atlantic salmon, a governance model for fisheries management with modernized policy frameworks, a policy that parallels Canada’s Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon,Footnote 4 and a commitment of the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture MinistersFootnote 5 to improve stewardship of fish and fish habitat. For continuing relevancy in rapidly changing conditions, the policy should be reviewed at five year intervals.

Wild Atlantic Salmon – A Renewed Management Approach

What is the status of wild Atlantic salmon and what has been done about it?

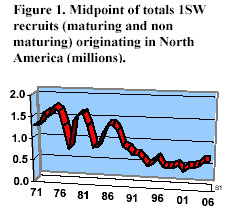

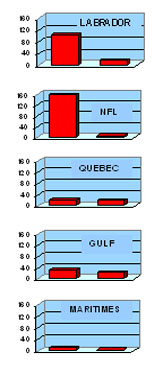

Between 1971 and 1985, the estimated abundance of North American, essentially Canadian, Atlantic salmon at one sea winter (1SW) of age fluctuated between 0.8 - 1.7 million fish annually (Fig.1). Between 1995 and 2006, the estimated abundance declined to about 0.4 - 0.7 million fish. The largest decline occurred in the age component destined to return to Canadian rivers as two-sea-winter (2SW) salmon.Footnote 6 As a result, the largest changes in status have been observed in the rivers from the southern portion of the species range as well as in the multi-sea-winter salmon stocks of Québec and Newfoundland and Labrador rivers adjacent to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Relative spawner abundances for the DFO Newfoundland (and Labrador), Gulf and maritime regions as well as the Province of Quebec for the period 1998-2007 are shown in Figure 2Footnote 7.

When pronounced declines in abundance were observed in the 1980’s, a wide range of management measures were introduced for conservation purposes.Footnote 7 The closures of commercial fisheries which began in 1972 in strategic intercepting and terminal fisheries were expanded in 1984 to include all the commercial fisheries of the Maritime Provinces and portions of Québec. Also in 1984, mandatory catch and release in the recreational fisheries of all large salmon was introduced in the Maritime Provinces and insular Newfoundland. These measures had the effect of increasing spawning escapements to most rivers of the Maritimes with subsequent responses in juvenile production. In contrast, overall escapements to Newfoundland were not consistent with ‘plan’ expectations. The failure of most stocks to rebuild in subsequent years to anticipated levels following the management measures of 1984 resulted in further reductions and eventually moratoria on commercial salmon fisheries in 1992 for insular Newfoundland, 1998 for Labrador and 2000 for all commercial fisheries in eastern Canada. Since then, more restrictive management measures have been introduced in an attempt to compensate for declining marine survival and salmon abundance, including reduced daily and season bag limits, mandatory catch and release of large and in some cases all sizes of salmon, and in large portions of the Maritimes the total closure of the recreational fisheries. Several Aboriginal community fisheries have been reduced and, in some cases, voluntarily suspended.

Figure 2. Median numbers of spawners (1,000’s), 1998-2007 (‘Gulf’ is SMA’s 15-18 and ‘Maritimes’ is SMA’s 19-23 per Figure 4.)

The most severe declines in abundance have been reported in the 32 rivers of the inner Bay of Fundy where Atlantic salmon have been designated as “endangered” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) and listed under Canada’s Species at Risk ActFootnote 3 (SARA). Numerous rivers in the Southern Upland of the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia are either threatened with extirpation or already have been extirpated.

Counts of smolts and returning adult salmon over the last several decades at about a dozen facilities in Atlantic Canada provide indices of natural survival at sea. Such index values remain variable and inconsistent but indicate that survival of populations to home waters has not increased as expected as a result of the closure of terminal and most sea fisheries.

The causes of the decline in abundance of Atlantic salmon have stimulated two intensive reviews by DFO, one following the exceptional low return of salmon in 1997Footnote 8 and a second workshopFootnote 9 at Dalhousie University in June 2000. The latter identified 62 possible factors and research initiatives which could lead to a better understanding of the factors and possible interventions to arrest the decline in Atlantic salmon. Despite these reviews, the factors contributing directly to reduced marine survival of Atlantic salmon remain largely unknown, while the factors in fresh water that have constrained productivity are much better understood – acid rain in the Southern Upland rivers of Nova Scotia and poaching in marine and freshwaters of Newfoundland and Labrador).

Who values salmon?

Wild Atlantic salmon are an important heritage of Atlantic Canada and Québec. They are an indicator of environmental quality, an object of respect, a target of eco-tourism and have a value that goes beyond the social and economic values associated with salmon fisheries. Streamlined, silver and graceful, whether swimming up or down river or jumping waterfalls, the Atlantic salmon has generated a rich cultural heritage based largely on the mystique of the fish itself. Eco-tourism is gaining momentum as people just want to catch a glimpse of this symbol of healthy river systems

Atlantic salmon are fished for food, social, and ceremonial purposes by more than 40 First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations in Atlantic Canada and Québec. For both coastal and inland Aboriginal people, salmon have been and continue to be important culturally as a food source. Working with First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations is an essential part of salmon management and restoration.

Of course, Atlantic salmon has been of considerable importance to all Canadians living in Atlantic Canada and Québec. Prior to the 1980’s, this heritage was perhaps more focused on commercial salmon fisheries (although subsistence uses were common and important throughout the region from the time of their arrival). However, with the recent downturns in abundance of some stocks, the focus now is more on community level conservation as well as on the related high value recreational fisheries and the socio-economic opportunities they provide. The growing acceptance of catch-and-release fisheries has also permitted the co-existence of both a fishery and maximization of escapements. The recreational fishing industry for wild Atlantic salmon in Atlantic Canada and Québec contributes over $56 million in attributable expenditures to local and provincial economies annually.

Why a new approach to Atlantic salmon management and how?

DFO resources directed towards wild Atlantic salmon

In the fiscal year 2004-05, DFO expended more than $12M; this is less than one-half the expenditures in 1984-85. Similar reductions have occurred on other important Atlantic fish species which continue to support commercial fisheries. Some of these reductions have been redirected to a large suite of new priorities.

There have been calls for the federal government to take urgent action to help arrest the dramatic overall decline and to rebuild wild Atlantic salmon populations. There has been an increasing awareness that the importance of genetic diversity had not been adequately addressed in past management of salmon fisheries and its habitat. A new approach to managing salmon production and diversity is needed to conserve salmon and protect and restore the full array of benefits they provide to Canadians.

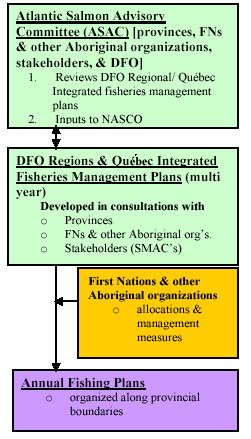

The new approach envisages more efficient and effective use of internal and external resources already available to achieve conservation objectives for wild Atlantic salmon. This is an approach that recognizes that DFO alone cannot address all of the challenges facing wild Atlantic salmon. The Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy, therefore, needs to set the stage for all internal and external parties to more effectively contribute to conservation objectives through shared stewardship.

Shared stewardship involves DFO actively collaborating externally with Provincial governments, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, volunteers, other stakeholders and other federal agencies to conserve and restore salmon and salmon habitat. In addition, leadership by DFO in international salmon conservation fora will play a key role in identifying and addressing conservation issues in the marine environment.

The impetus for a new management approach also comes from the evolution in public attitudes, science, laws, and decision making over the past 20 years. Thousands of volunteers and many local watershed groups now actively protect and restore Atlantic salmon and habitat. Indeed, it is clear that Atlantic salmon has benefited greatly from the work of these individuals and groups. SARA mandates the protection of listed wildlife species at risk and their critical habitat. The Oceans ActFootnote 10 calls for integrated resource management and an ecosystem perspective. Provinces, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, and non-governmental organizations are demanding more involvement in decision making about wild Atlantic salmon.

The Department has been giving increasing importance to sharing stewardship with resource users and other interested parties. The complexity and cost of protecting, restoring, and enhancing salmon populations and habitat require cooperation among DFO, provinces, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, community and other stakeholders,Footnote 11 all of whom have an important role to play. The future of wild Atlantic salmon benefits from the involvement and dedication of these groups, collaborating with governments, as well as strategic investments by the Government of Canada. Expectations for the management of Atlantic salmon today require a proactive, forward-looking approach that sets clear conservation goals and acknowledges the importance of protecting biodiversity for sustaining diverse healthy wild Atlantic salmon populations, their habitats, and associated sustainable use. Together with the enjoyment wild Atlantic salmon provide, their place in our cultural identity, and the expectations of Canadians for responsible stewardship, these factors make a compelling case for a new policy approach. This draft of the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy takes account of consultations with First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, the Provinces, and other stakeholders at sessions held in May-June 2005 on the draft discussion paper released in March 2005 as well as comments received through regional consultations and then DFO website concerning the May 2007 Draft Policy.

The policy that follows will guide future decisions to conserve wild Atlantic salmon and their habitat and will facilitate an adaptive approach to salmon conservation. It neither amends nor overrides existing legislation or regulations but will govern how these statutory authorities will be implemented. The policy defines objectives and describes conservation outcomes, but it does not prescribe decision rules that would restrict its application. It is believed that the approach set forth in this policy offers increased opportunities for the consideration of alternatives, such as habitat initiatives, to assist in addressing protection and rebuilding of wild Atlantic salmon populations. Finally, the approach selected is compatible with the Fisheries ActFootnote 12, the Species at Risk Act, and the Oceans Act.

Legal Context for the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy

The federal and provincial division of powers is set out in the Constitution Act, 1867.Footnote 13 Pursuant to Subsection 91(12) the Parliament of Canada has exclusive legislative authority for all matters relating to “Sea Coast and Inland Fisheries”. Under that head of power, Parliament enacted the Fisheries Act, which gives the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans the authority to manage and protect the resource, to provide access to the resource, and to impose appropriate conditions on harvesting. The Parliament of Canada also has exclusive legislative authority in matters relating to “Public Debt and Property” (91(1A)), “Navigation and Shipping” (91(10)), and “Indians and Lands Reserved for the Indians” (91(24)), which, to some degree, are also relevant to this policy.

Subsection 92(13) specifies that the legislature in each province may exclusively make laws in relation to “property and civil rights in the province”. The provincial legislatures also have exclusive power to legislate in matters relating to “management of public lands” (92(5)), and “matters of a merely local or private nature in the Province” (92(16)). Under these heads of power, provincial legislatures have enacted various statutes dealing with land, water, environment, waste disposal, and fisheries. Pursuant to these laws, provincial governments have powers with respect to, amongst others, the harvesting of salmon in inland waters: they issue licences for recreational angling for salmon and other species, and they collect fees for these licences. They have also adopted provincial regulations setting conservation measures such as angler licensing and fish tagging requirements. It is to be noted that provinces may delegate some of those powers to municipalities.

In addition, the Quebec government also has additional delegated powers with respect to fisheries administration, which apply to the management and control of fishing for freshwater fish, as well as anadromous and catadromous species of fish in the waters of the Province and in tidal waters. This delegation is now reflected in the Quebec Fishery Regulations, 1990,Footnote 14 DFO remains responsible for the application of the Fisheries Act provisions dealing with the conservation and protection of fish habitat in watercourses in Québec, but Quebec delivers some aspects of this responsibility.

Loss of Species Diversity

Concern for diversity in Atlantic salmon emerged in the Maritime Provinces in the early 1980s, after acid precipitation, with consequential mortality in fresh water, had extirpated salmon in 14 of 65 rivers of the Southern Upland of Nova Scotia. In another 20 rivers, the pH partially impacted salmon populations and enhanced their risk of extirpation[1]. More recent projections[2] suggested that extirpations in the Southern Upland area had likely doubled from those of the early 1980s due to unchanged or worsening pH conditions and reduced marine survival. In the nearby inner Bay of Fundy rivers unaffected by acid rain, the numbers of returning wild salmon declined even more precipitously as a result of high marine mortality.

Several published[3,4] and unpublished studies indicated that salmon of the Southern Upland, the inner Bay of Fundy and elsewhere in Atlantic Canada were genetically distinct from each other (See side bar p16), and were instrumental in the designation of the inner Bay populations as “endangered” in 2001 and their listing under SARA in 2003. Atlantic salmon populations of the Southern Upland region of Nova Scotia and outer Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick and the loss of their diversity remain of particular concern to DFO.

[1] DFO (2000), The Effects of Acid Rain on the Atlantic Salmon

of the Southern Upland of Nova Scotia.

[2] Amiro, P.G. 2000. Assessment of the status, vulnerability

and prognosis for Atlantic salmon stocks of the Southern Upland

of Nova Scotia

[3] Verspoor et al. (2002), ‘Restricted matrilineal gene flow

and regional differentiation among Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar

L.) populations within the Bay of Fundy, Eastern Canada’.

[4] Verspoor, E. (2005), ‘Regional differentiation of North American

Atlantic salmon at allozyme loci.’

The legal context for management of wild Atlantic salmon is also shaped by court decisions respecting Aboriginal and treaty rights. Existing Aboriginal and treaty rights are recognized and affirmed in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.Footnote 13 In its 1990 decision in R. v. SparrowFootnote 15, the Supreme Court of Canada held that the recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal rights in the Constitution Act, 1982 means that any infringement of such rights must be justified. As described in more detail in Appendix 1, DFO seeks to manage fisheries in a manner consistent with the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. SparrowFootnote 15 and subsequent court decisions. Specifically, DFO is committed to managing fisheries such that Aboriginal fishing for food, social and ceremonial purposes has priority over other fisheries.

Atlantic Salmon and Diversity

The health of Atlantic salmon depends not only on their abundance but also on their biological diversity. That diversity includes the irreplaceable lineages of salmon that have evolved through time, the geographic distribution of these populations, the genetic differences and life history variations observed among them, and the habitats that support these differences. Diversity of Atlantic salmon represents their legacy to date and their potential for adaptation to future changes in climate and habitat. Protecting diversity is the most prudent policy for the future continuance of wild Atlantic salmon as well as the ecological processes that depend on them and the cultural, social, and economic benefits drawn from them.

Diversity is lost as populations or their range diminishes. COSEWIC can, when requested, oversee an assessment of the rate of decline in distinct populations segments/ subpopulations or their range to determine the degree to which they are in jeopardy, and need of elevated protection. Aside from the afore-mentioned inner Bay of Fundy populations, no other Atlantic salmon populations have yet been assessed by COSEWIC. Significant declines and extirpations in the southern limits of the salmon’s Canadian range do however suggest the possibility of other candidates for elevated protection against the loss of species diversity. Extirpations, listings and obvious declines in diversity are one, indeed major, impetus for a new management approach for wild Atlantic salmon.

The Importance of Habitat and Ecosystems

To survive and prosper, wild Atlantic salmon depend on appropriate freshwater and marine habitat: no habitat, no salmon. The Fisheries Act defines fish habitat as “Spawning grounds and nursery, rearing, food supply and migration areas on which fish depend directly or indirectly in order to carry out their life processes.” Healthy, abundant, productive and accessible habitat indirectly provides substantial social benefits to Canadians and international tourists who are drawn to Atlantic Canada and Québec each year for recreational salmon fishing and eco-tourism. However, the land and water that comprise salmon habitat also provide valuable economic opportunities in a wide range of non-fishery-related sectors, such as urban and riverfront development, forestry, agriculture, energy (hydroelectric dams, oil and gas), aquacultureFootnote 16 provision of drinking water and others. Productive habitat in Atlantic Canada faces growing pressures from human activities that threaten capacity to sustain wild Atlantic salmon populations over the long term. In addition, competing uses pose a challenge for maintaining healthy, abundant, productive and accessible habitat for Atlantic salmon and other species. Further, there is a concern that habitat accessibility and productivity can deteriorate resultant of many small, incremental and often unidentified impacts that accumulate over time. Finally, ocean and freshwater habitat of Atlantic salmon can be affected by global-scale phenomena, such as climate change through, for example, changing precipitation and temperature patterns affecting the ocean ecosystem, migration routes of salmon, as well as salmon habitat in rivers and streams.

The challenge is to ensure that social and economic activities are conducted in such a way to avoid or mitigate adverse effects on wild Atlantic salmon habitat and to maintain access to productive habitat.

Salmon Diversity and Biodiversity

The diversity in Atlantic salmon described above refers to genetic variation and adaptations to different environments that have accumulated between populations of salmon. The abundance of spawning salmon is understood to be important for the future production of salmon, and it is also critical for the maintenance of genetic variation or diversity within populations, and for fidelity of populations that results from straying. A low level of straying between spawning groups provides an important source of genetic variation and provides for colonization of new habitats. In this policy, the term diversity, or salmon diversity, refers to genetic variation and adaptations within and between populations of wild Atlantic salmon.

In addition, wild Atlantic salmon are part of a larger ecosystem as components of the total biological diversity. In this policy, biological diversity (“biodiversity”) is defined as the full range of variety and variability within and among populations and the ecological complexes in which they occur. Biodiversity also encompasses diversity at the ecosystem, community, species, and genetic levels and the interaction of these components. The protection of biodiversity and understanding of the broader implications of this term are also essential to the implementation and success of this policy. The biodiversity associated with wild Atlantic salmon populations will as well influence the quality and productivity of the salmon’s ecosystems and local habitats and determines the biological background influencing salmon diversity and their adaptability. The SARA recognizes the importance of the diversity within species by defining “wildlife species” to mean “a species, sub-species, variety or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal that is wild by nature and (a) is native to Canada; or (b) has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.”Footnote 17This Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy will include specific plans to define such “geographically or genetically distinct populations” of wild Atlantic salmon and the habitats necessary to protect their biodiversity and, as such, adhere to the definition of “wildlife species” in the SARA.

POLICY FOR THE CONSERVATION OF WILD ATLANTIC SALMON

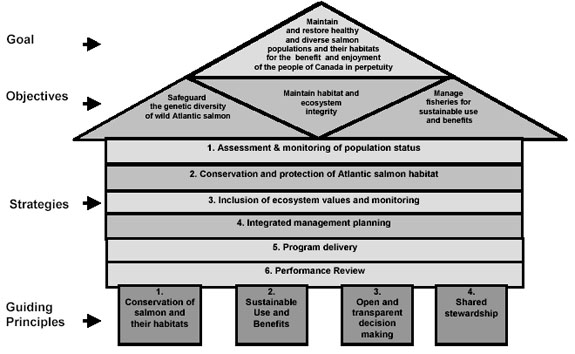

This policy describes how DFO will meet its responsibilities for the conservation of wild Atlantic salmon. It stipulates an overall policy goal for wild salmon, identifies basic principles to guide resource management decision making, and sets out objectives and strategies to achieve the goal (Figure 3).

The implementation of this policy should lead to:

- Healthy, diverse, and abundant wild salmon populations for future generations;

- Sustainable fisheries, to meet the needs of First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations and contribute to the current and future prosperity of all Canadians; and

- Inclusion of ecosystem considerations in management decisions.

Figure 3. Overview of the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy

GOAL AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Important Terminology: Conservation and Sustainable Use and Benefits

The terms- "Conservation" and “Sustainable Use and Benefits" mean different things to different people. Some definitions of conservation include sustainable use, implying that protection of the biological processes and use of resources are both components of conservation. Other definitions, such as in the Convention on Biological Diversity, separate the two concepts and present them as related, but distinct considerations. In this Policy, these terms are defined as follows:

“Conservation” is the protection, maintenance, and rehabilitation of genetic diversity, species, and ecosystems to sustain biodiversity and the continuance of evolutionary and natural production processes[1].

This definition identifies the primacy of conservation over use, and separates issues associated with constraints on use from allocation and priority amongst users.

“Sustainable Use and Benefits” is the use of biological resources in a way and at a rate that does not lead to their long-term decline, thereby maintaining the potential for future generations to meet their needs and aspirations.

As a resource management agency, DFO is committed to the sustainable use and benefit of wild salmon resources. The intent of this Policy is to protect the biological foundation of wild Atlantic salmon to provide the fullest benefits now and for future generations. In the long term, protection of biodiversity will provide the greatest opportunity for maintaining sustainable benefits to Canadians.

[1] see Shuter et al. (1997), Grumbine (1994), Mangel et al. (1996) and Olver et al. (1995).

The goal of the ‘Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy’ is to maintain and restore healthy and diverse salmon populations and their habitat, for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of Canada in perpetuity.

All decisions and activities pertaining to the conservation of wild Atlantic salmon will be guided by four pinciples:

Principle 1 - Conservation. Conservation of wild Atlantic salmon, their genetic diversity and their habitats is the highest priority in resource management decision making.

The protection and restoration of wild Atlantic salmon and their habitats will enable the long-term health and productivity of wild populations and continued provision of cultural, social, and sustainable benefits. To safeguard the long-term viability of wild Atlantic salmon in natural surroundings, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans will strive to maintain healthy and genetically diverse populations.

Allocations to First Nations and other Aboriginal Organizations

Resource management processes and decisions will provide for allocations to First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations for food, social, and ceremonial purposes. They will also provide for consultation with First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations. Resource management processes and decisions will also be in accordance with any treaties or agreements entered into between Canada and First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations.

Principle 2 - Sustainable Use and Benefits. Resource management decisions will consider biological, social, and economic con-sequences; they will reflect best science including Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK) and local knowledge, and they will maintain the potential for future generations to meet their needs and aspirations.Footnote 18

The maintenance of biodiversity and healthy ecosystems must be considered in the context of human values now and in the future. Decisions will be made taking into account their costs and/or social consequences.

Diversity in Atlantic salmon reflects genetic and habitat diversity and the evolution of lineages of salmon over thousands of years22. These precise lineages cannot be replaced once lost, and the more numerous they are the greater the chances for salmon to adjust to future environmental changes. Diversity is a kind of insurance that reduces the risk of loss by increasing the likelihood that species and populations will be able to adapt to changing circumstances and survive. Also, maintaining the largest number of spawning populations that are adapted to their individual habitats will result in higher abundances of salmon.

We still have much to learn about the importance of local adaptations at the stream level, the rate at which salmon adapt, and the value of biodiversity. However, since no one can foresee the future stresses on wild salmon, a responsible and precautionary approach recommends conserving a wide diversity of populations and habitats. Atlantic salmon have been diverse and adaptable enough to survive floods and drought, disease, volcanic eruptions, and ice ages. Their survival strategies may continue to serve them in the future unless human-caused pressures become insurmountable. We must ensure that these survival strategies are allowed to function and not destroyed by our growing human footprint. Most aggregations of Atlantic salmon will encompass large areas and include many streams and localized spawning groups. Concerns have been expressed that for large aggregations, individual streams and spawning groups may not be adequately protected even if they are important to local communities. All local spawning groups and streams have value. In practice, protecting large aggregations with their networks of spawning groups is the most effective way to protect individual spawning groups and the interests of local communities.

Principle 3 - Open and Transparent Decision Making.

Resource management decisions will be made in an open, transparent,

and inclusive manner.

To gain broad public support for decision making, salmon management must accommodate a wide range of interests in the resource. Decisions about salmon protection and sustainable use will be based on meaningful input from all interested parties to ensure they reflect society’s values. Decision making processes will be transparent and governed by clear and consistent rules and procedures.

Principle 4 – Shared Stewardship. Conservation initiatives will be optimized by actively engaging provincial governments, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, volunteers and other stakeholders in the development, implementation, promotion, maintenance of, and compliance with management decisions, while DFO maintains it’s legislative authority towards the conservation of Atlantic salmon and its habitat.

It is important to provide an inclusive approach to allow First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, and other stakeholders to play a greater and more meaningful role in decision making and thus take more responsibility for those decisions and their outcomes. Promotion of and compliance with management measures is most effectively achieved when First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, and other stakeholders and resource users are directly involved in the development and implementation of the measures, including monitoring for compliance.

Article 6.2 of the UN Agreement ‘Relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks’ 1995, proclaims that “States shall be more cautious when information is uncertain, unreliable or inadequate. The absence of adequate scientific information shall not be used as a reason for postponing or failing to take conservation and management measures.” The Article builds on the original declaration of a precautionary approach (Principle 15, Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992), and is also included in the United Nations Fisheries and Agriculture Organization (FAO) “Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries” (1995)[1]

Precautionary approaches are now widely applied in fisheries management and the protection of marine ecosystems. The approach identifies important considerations for management: acknowledgement of uncertainty in information and future impacts and the need for decision making in the absence of full information. It implies a reversal in the burden of proof and the need for longer term outlooks in conservation of resources.

The application of precaution in the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy will follow the guidance provided to federal departments by the Privy Council Office publication[2] entitled “A Framework for the Application of Precaution in Science-based Decision Making About Risk." (Canada, Privy Council Office 2003). That framework includes five principles of precaution:

- The application of the precautionary approach is a legitimate and distinctive decision making approach within a risk management framework.

- Decisions should be guided by society’s chosen level of risk.

- Application of the precautionary approach should be based on sound scientific information.

- Mechanisms for re-evaluation and transparency should exist.

- A high degree of transparency, clear accountability, and meaningful public involvement are appropriate.

The Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy will adhere to the use of precaution and be consistent with the Privy Council Office framework and FAO (1995, paragraph 6 (a-h)). For example, the introduction of a lower benchmark e.g., egg deposition level in the 1986 policy (Strategy 1 here-in) was a significant precautionary step in the conservation of Atlantic salmon. In determining the value of the benchmark, all sources of uncertainty in assessment of the indicator system and SMA must be determined (for estimation of the buffer) and the Department and advisors must determine a risk tolerance to be applied in a risk management framework. Where assessment information is highly uncertain, a lower risk tolerance would likely be chosen.

[1] also see FAO (1995);

[2] see http://www.pco-bcp.gc.ca/index.asp?lang=eng&page=information&sub=publications&doc=precaution/precaution_e.htm

OBJECTIVES

In order to achieve the outcome expressed in the policy goal for the conservation of wild Atlantic salmon, three objectives must be fulfilled:

- Safeguard the genetic diversity of wild Atlantic salmon;

- Maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity; and

- Manage fisheries for sustainable use and benefits.

Implementation of these policy objectives must and will be consistent with the Precautionary Approach (PA), namely that management agencies must be more cautious when information is uncertain and the absence of adequate scientific information cannot be used as a reason for postponing or not taking appropriate conservation measures (also see adjacent text box). Key considerations associated with each of these objectives are described below.

Objective

1: Safeguard the genetic diversity of wild Atlantic salmon.

To sustain Atlantic salmon and their associated benefits, it is

necessary to safeguard their geographic and genetic diversity and

their habitats (see “Maintenance of diversity in

Atlantic salmon” text boxFootnote 19). While maintaining

diversity is broadly accepted as essential for the health of wild

salmon, the significant scientific and policy issue is, “how much

diversity?” The genetic diversity of a species includes every individual

fish. Preserving maximum genetic diversity would eliminate human

harvesting of Atlantic salmon and prohibit any human activity that

might harm salmon or their habitat. Conversely, to maintain Atlantic

salmon just at the species level but to ignore within-species population

structures would reduce diversity and contravene the intent of the

Precautionary Approach, the United Nations Convention on Biological

Diversity, the SARA, and, notably, the intent of this policy.

Atlantic salmon have a complex hierarchical population structure extending from groups of salmon at individual spawning sites all the way up to the taxonomic species. Their nearly precise homing to natal streams restricts gene flow among fish at different spawning locations. However, since some salmon stray, genetic exchange also occurs among fish from different persistent spawning sites (demes) in a geographic area. These interactions form a geographic network of demes and the basic level of genetic organization in Atlantic salmon.

The likelihood of genetic exchange decreases with increased distance between streams or with greater environmental differences between streams. Fewer strays and less genetic mixing result in less genetic similarity between fish in these streams. Eventually, as geographic distance or environmental differences grow to severely limit gene flow, the spawning groups will function as separate lineages. These independently functioning aggregates are defined as Conservation Units in this Policy.

Between localized demes and the geographic boundary of a CU are usually intermediate groupings called Populations. A population is a group of interbreeding salmon that is sufficiently isolated (i.e., reduced genetic exchange) from other populations such that persistent adaptations to the local habitat can develop over time. Local adaptations and genetic differences between populations are an essential part of the diversity needed for long-term viability of Atlantic salmon.

DFO intends to safeguard diversity by:

- recognizing genetic diversity as the basis for management of Atlantic salmon, regardless of the level of that management,

- managing Atlantic salmon within existing Salmon Management Areas (SMAs ) (Figure 4; also see adjoining “Population structure” text box).

- If or when the population status of a group of salmon at the SMA level is at a point of significant decline, management actions would be taken so as to minimize loss of genetic diversity at the SMA, and ultimately, the “Conservation Unit” (CU).Footnote 20 A CU is a group of wild salmon sufficiently isolated from other groups that, if extirpated, is very unlikely to recolonize naturally within an acceptable timeframe, e.g., human lifetime or a specified number of salmon generations (also see adjoining text box for further details) Managing at the CU level (as is planned for Pacific salmon on Canada’s West Coast) is a worthy objective that will be attained, once CU’s for Atlantic salmon have been scientifically defined.

Conservation Units for Atlantic salmon

Analyses of genetic markers can provide information on the extent of differentiation and reproductive isolation among salmon from different rivers and geographic areas which, along with ecological, life history, tagging, and other information can be useful in helping to delineate CUs. Few population genetics studies of Atlantic salmon have been carried out at the appropriate spatial scale in the species’ Canadian range. At this time, only the inner Bay of Fundy populations [SMA 22 and part of SMA 23 (Fig. 4)] could, arguably, be designated as a CU[1]. Ecological, life history, and molecular genetic information is required to delineate Atlantic salmon CUs throughout their Canadian distribution.

[1] King et al (2001), Verspoor et al (2002), Verspoor (2005), Verspoor et al (2005), O’Reilly and Cox (2005)

At this time, in Atlantic Canada and Québec, there is, with one exception (inner Bay of Fundy salmon populations), insufficient published information with which to delineate Conservation Units that would safeguard remaining genetic diversity. The eventual delineation of CUs will be based on biological information, including data from molecular genetic markers (essential in identifying ancestral lineages of salmon and to estimate gene flow among populations), phenotypic information (life history, morphology, meristics), ocean distribution data, Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK) where available, and public consultation. Since the requirements and needs of First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations and other interested parties may be at finer geographic scales than CUs and most SMAs , management objectives to address these may be recognized in integrated fisheries management plans (Strategy 4).

There are important implications to the safeguarding of genetic diversity. The persistence of populations and associated production demand responsible management of its populations, watersheds,Footnote 21 and habitats as well as the ability of fish to move among habitat areas (connectivity). The loss of a population (e.g. in an index river) and, by possible inference, an SMA/CU would clearly have serious consequences for the people and other ecosystem components that benefit from or depend on it.

Over the geographic area of an SMA, variations in habitat type and quality may result in differences in salmon productivity. Such differences in nature mean that not all populations within an SMA are likely to be maintained at equal levels of production or chance of loss. Maintaining SMAs requires protecting populations and demes (see text box above) but not necessarily all of them all of the time. As long as networks of connected demes and streams within SMAs are maintained, any loss of a localized spawning group should be temporary. Maintaining healthy abundances within SMAs requires sufficient spawning salmon to re-colonize depleted spawning areas and protection of fish habitat to support production and maintain connection between localized spawning groups. While salmon from neighbouring demes or populations are unlikely to be genetically identical to those lost, they are likely to be most similar genetically and share many adaptive traits. Such localized losses, whether due to natural events or human activities, would not result in extirpation of the populations within the SMA.

Total success in safeguarding the genetic diversity of wild Atlantic salmon would imply preserving all populations within SMAs . Action steps in this policy are prescribed to maintain populations in SMAs and CUs to the fullest extent possible, but there will likely be circumstances when losses of wild salmon are unavoidable. Catastrophic events are beyond human control and the Department may not be able to restore habitat or spawning demes damaged by such events. The rate of climate change in an area may exceed the ability of some salmon populations to adjust. While it is the clear intent of this policy to prevent losses in genetic diversity resulting from management and use, it is unrealistic in natural environments to expect that all losses can be avoided.

Objective 2: Maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity.

The health and long-term well-being of wild Atlantic salmon is inextricably linked to the availability of diverse, healthy and productive freshwater, coastal, estuarine and marine habitats.

Linking Habitat to Wild Salmon populations within SMAs and Fish Harvest Planning

A key response of the regional Habitat Management Program to the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy is an increased emphasis on integrated planning. Fish production and harvest objectives for wild salmon populations within SMAs will be linked to the conservation, restoration, and development of fish habitat.

Through integrated resource planning, more effective and efficient conservation, protection and restoration of habitat can be achieved as a result of integrating habitat requirements with fisheries management objectives. Resulting habitat management plans will incorporate knowledge of the current and future demands on the aquatic resources, and will be aligned with objectives for fisheries and other resource users within watersheds.

Aquatic habitats and their adjacent terrestrial areas are also valued for a wide range of human uses. The integrity of salmon habitat is challenged by human demand for accessible land and fresh water, for ocean spaces, and for the interconnecting estuarine and coastal areas. In both freshwater and estuaries and near-shore marine areas, human activities can affect the biological, physical, and chemical components of salmon habitat resulting in adverse impacts during critical spawning, rearing, and migration periods. In the open ocean, activities such as commercial fishing, shipping, and waste disposal among others can potentially affect the marine habitat of salmon.

Identifying, protecting habitat and, restoring and rehabilitating degraded aquatic habitats are critical to maintaining their integrity and sustaining ecosystems and the benefits they provide to Canadians. The Fisheries Act contains specific provisions that provide DFO’s Habitat Management Program with the regulatory framework for the conservation and protection of fish and fish habitat. The habitat protection and pollution prevention provisions of the Fisheries Act are set out in the following provisions:

Sections 20, 21 and 22: Gives the Minister the authority to require the construction, maintenance and operation of fish passage facilities at obstructions in rivers; to require financial support for fish hatchery establishments constructed and operated to maintain runs of migratory fish; to remove unused obstructions to fish passage; and to require a sufficient flow of water at all times below an obstruction for the safety of fish and the flooding of spawning grounds.

Section 30: Gives the Minister the authority to require the installation and maintenance of screens or guards to prevent the passage of fish into water intakes, ditches, canals and channels.

Section 32: Prohibits the destruction of fish by means other than fishing, except as authorized by the Minister or under regulations.

Section 35(2): Prohibits works or undertakings that result in the harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat, unless authorized by the Minister or under regulations.

Section 36: Prohibits the deposit of deleterious substances, except where authorized by regulation Currently there are regulations that authorize the deposit of pulp and paper liquid effluent, metal mining liquid effluent, petroleum liquid effluent, and effluents from other industrial sectors.

Environment Canada is responsible for administration and enforcement of Section 36 while DFO retains responsibilities for the administration and enforcement of the other provisions. The application of these provisions is guided by the Policy for the Management of Fish Habitat (DFO 1986) and related operational documents. The Habitat Policy includes: a policy objective of “net gain of habitat for Canada’s fisheries resources”; three goals (conservation, restoration and development); a guiding principle of “no net loss of the productive capacity of fish habitat” to support the conservation goal and eight implementation strategies that includes the concept of integrated planning for habitat management.

One of the key responsibilities of DFO’s Habitat Management Program is to evaluate proposed works or undertakings during the planning stages to determine the impact on fish and fish habitat. Where proposed works or undertakings can result in the harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish or fish habitat in or around water, the first and preferred approach to conserving fish habitat is to relocate or redesign the project so that the anticipated impacts are completely mitigated. Where it is not possible to completely mitigate the impacts of the proposed works or undertakings, DFO may authorize the loss of fish habitat as long as the loss can be off-set through the replacement or compensation of habitat using the hierarchy of preference in the Habitat Policy.

In recent years, the Habitat Management Program has modernized the delivery of its responsibilities. Over that time, a number of policies, programming and organizational changes have been undertaken to make the Program more effective, efficient, and relevant to Canadians (see Appendix 1 [Policy and Programs] for more details). The aim of the Program is to ensure that resources are focused on those areas requiring the greatest attention. With respect to Atlantic salmon, a focus on habitat that is most productive, limiting, or at risk in an SMA or a CU will clarify decision making and better link habitat management strategies to harvest fishing and salmon assessment (see Strategy 4). Low risk works or undertakings, where measures to avoid or mitigate impacts are well understood, will be dealt with through other mechanisms such as operational statements, guidelines and standards together with compliance and effectiveness monitoring and auditing.

It is important to note that, under the habitat protection provisions of the Fisheries Act, DFO does not authorize works or undertakings. Rather, it authorizes the negative impacts on fish and fish habitat associated with works or undertakings, where these impacts are deemed acceptable and compensable. The regulation of works or undertakings associated with land and water uses that may be detrimental to salmon resides with provincial or municipal level government. Success in conserving, protecting and restoring Atlantic salmon habitat demands a cooperative and collaborative approach among the various levels of government so that land and water use activities and decisions better support the needs of Atlantic salmon while recognizing the legitimate demands that other resource interests may make on the water resource. Therefore, DFO will strive to integrate its work with that of other federal government departments, provincial governments, municipalities, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, non-government organizations and voluntary groups and industries in order to effectively manage and protect salmon habitat in ways that recognize the priorities of Canadians.

Objective 3: Manage fisheries for sustainable use and benefits.

The conservation of wild Atlantic salmon and their habitat is the highest priority in this policy. However, a policy that fails to consider the value that Atlantic salmon fishing provides to people would be incomplete. While everyone supports conservation, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations and many others rely, to an important extent, on salmon for their food, social, economic, and recreational needs and insist on a balanced policy that provides for sustainable use of wild salmon.

DFO has a responsibility to provide sustainable fishing opportunities that will best meet its obligations to First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, contribute to social well-being, and provide economic benefits to individuals and communities. A significant challenge for this policy is to safeguard the various Atlantic salmon populations, watersheds and SMAs and their genetic diversity while accounting for and realizing the benefits of a sustainable use. Since access restrictions necessary to conserve the wild salmon resource affect communities and individuals; cultural, social, and economic impacts need to be considered.

While overemphasis of the social and economic benefits arising from salmon fishing can compromise salmon conservation, a single focus on maintaining diversity can also mean the elimination of salmon fisheries and/or other human activities in some areas. In reality, the interests of both salmon and people need to be accounted for in a successful conservation program. This policy describes a management framework that can provide care and respect for a resource and its ecosystem and for the people within it. Protecting the watershed provides the maximum potential for benefits to people. The full measure of the Wild Atlantic Salmon Conservation Policy’s success will be the achievement of salmon conservation accompanied by sustainable use and benefits.

The best decisions for salmon management cannot be made by any one group alone. While choices must certainly be informed by scientific and technical information, the best decisions will ultimately reflect public values. This requires structured processes that: (1) establish specific objectives and priorities and (2) allow the biological, social and economic consequences of different management measures and activities to be considered and weighed in an open and transparent way with respect to these objectives.

Management for sustainable use and benefits, is particularly important to the provinces who have a significant economic interest in many aspects of sustainable development and license sales represented in freshwater recreational fisheries. Furthermore, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, aquaculturists, recreational fishers and the recreational fishing industry, watershed groups, environmental groups, and community interests need to be engaged directly in these processes, and in the determination of the most appropriate management actions. Individual and community involvement in salmon management decision making, in turn, will sustain the social and cultural ties between people and salmon. These ties will ultimately lead to the more successful implementation of management plans and the better protection of wild Atlantic salmon.

The establishment of good management measures alone is not enough to ensure success in conserving and protecting a resource such as wild Atlantic salmon. An effective compliance program must be maintained to promote awareness of and compliance with management measures. Such a program must focus on promoting voluntary compliance, on monitoring legitimate fisheries and other activities for compliance, and on enforcement against those who violate. There are many examples of First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, and other stakeholder involvement in all of these compliance aspects (such as by local “River/ Conservation watch” or Stewardship groups, Crime stoppers-type programs, and Aboriginal Fishery Guardian and Community Compliance Monitor initiatives) – these should be expanded. Furthermore, provinces have strong compliance programs regarding Atlantic salmon; these need to be fully recognized when developing an overall, improved and coordinated compliance approach as advocated under this policy

STRATEGIES AND ACTION STEPS

This policy will be implemented through six “strategies” and related “action steps” as summarized in Table 1. Strategies 1 through 3 will provide the information on wild Atlantic salmon populations, their habitats, and ecosystems required for decision making and planning necessary to meet Objectives 1 and 2. Strategy 4 requires the integration of biological, social, and economic information to produce integrated fisheries management plans for salmon and habitat management for each SMA i.e., Objective 3. Strategy 5 is the translation of integrated fisheries management plans into operational plans and Strategy 6 is a commitment to ongoing review of the implementation and success of the policy.

| 1. Assessment and monitoring of population status |

|

| 2. Conservation and protection of Atlantic salmon habitat |

|

| 3. Inclusion of ecosystem values and monitoring |

|

| 4. Integrated fisheries management planning |

|

| 5. Program delivery |

|

| 6. Performance review |

|

STRATEGY 1: ASSESSMENT AND MONITORING OF POPULATION STATUS

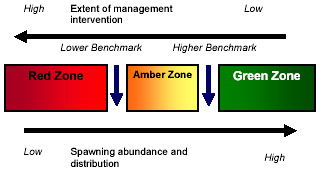

Having populations in the Red Zone is undesirable because of the loss of ecological benefits and salmon production. The presence of a population(s) in the Red Zone will initiate immediate consideration of ways to protect the fish, increase their abundance, and reduce the potential risk of loss. Biological considerations will be the primary drivers for management of populations with Red status.

Amber status implies management with caution. While populations in the Amber Zone should be at a low risk of loss, there will be a degree of lost production. Decisions about the conservation of populations in the Amber Zone will involve broader consideration of biological, social, and economic issues. Assuming a population is assessed to be safe in the Amber Zone (consistent with Principle 1), then the use of adjacent populations involves a comparison of the benefits from restoring production versus the costs arising from limitations imposed on the use of other populations to achieve that restoration.

Social and economic considerations will tend to be the primary drivers for the management of populations in the Green Zone, though ecosystem or other non-consumptive use values could also be considered.

This policy requires a systematic process to monitor abundance and distribution of Atlantic salmon over time. It supports fisheries management renewal in changing the role of users of fisheries resources (e.g. recreational fishing industry, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations) by working in closer collaboration to manage the resource, collect scientific data and conduct fisheries assessments. Research will be peer reviewed and include support from academic partners. The following action steps present how the responsible government agencies will identify and assess wild Atlantic salmon populations within SMAs in their respective jurisdictions, in cooperation with provincial governments, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, and other stakeholders.

Action Step 1.1. Develop criteria to assess SMAs and identify benchmarks to represent biological status.

The biological status of SMAs will normally be based on the abundance and distribution of spawners in index river(s). For an index river, higher and lower benchmarks will be identified that delimit three status zones: green, amber, and red (Figure 5). As spawner abundance decreases in an index river, a population and, presumably, its SMA moves towards the lower status zone and the probability of management intervention for conservation purposes will increase. Whereas the lower benchmark could be considered as a criterion to protect the resource, the higher benchmark could be considered a level to optimize its use.

Benchmarks identify when the biological production status of an index river and presumably SMA, have changed significantly but they are not necessarily prescriptive. Changes in status will initiate management actions (see text box above). The specific responses will vary among geographic regions and cause of the decline and will be assessed through the integrated fisheries management planning process described in Strategy 4. The use of status zones and generic methods to determine benchmarks recognizes variability in data quality and quantity and is consistent with current management approaches adopted by other agencies.Footnote 22

In this Policy the lower benchmark between Amber and Red will be established as the level of abundance high enough to ensure there is a substantial buffer between it and the level of abundance that could lead to an index river(s), and SMA being at considerable risk of serious harm. The buffer should account for uncertainty in data, the understanding of population dynamics, and control by fisheries management. The general rule used for a number of years for determination of the lower benchmark for Atlantic salmon in Atlantic Canada has been the conservation egg deposition rate of 2.4 eggs per m2 of rearing habitat. Similar conservation and egg deposition rates, but at different levels, have been established for rivers in Eastern Canada. These conservation egg deposition rates have been regarded as proxies for the level of spawners which would result in the maximum sustained yield (MSY) or in some literature, spawners for optimum yieldFootnote 23 which equate to the ‘conservation limit’Footnote 24 used in regional, national, and international fisheries management. Obviously, there is significant potential to modify these criteria on a river/ SMA-specific basis. Examples of criteria which could be considered, based on detailed biological information, areFootnote 25:

- The spawning escapement which produces, on average, a percentage (e.g., 50-75%) of the maximum juvenile abundance;

- The abundance and distribution of spawners within an index river(s) and SMA sufficient to provide confidence that the population(s) and SMA are at a low risk of serious harm (e.g., <5% chance over 50 years).

Within the Red Zone, the population is at a level of abundance at which further mortalities will lead to continued decline in the spawner abundance and an increasing risk of serious harm. Determining this level in the zone is an unresolved issue and is not specified in this policy. The determination of the risk tolerance is one that requires consultation with resource users affected by this choice. The respective government agencies will over time prepare and publish operational guidelines on the estimation of this level. The management response to this level will be assessed on a case-by-case basis in consultation with First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations and others affected by this determination.

The higher benchmark between Green and Amber should identify a management target with the intention of providing optimum use of the resource. As with the lower benchmark, the upper benchmark will be established on a case-by-case basis depending on the intended use, the regulatory framework in place and the types of information available. This level may change through time but there would be a near negligible probability of losing the population(s) and SMA. The determination of this benchmark is also a value judgement that requires consultation with all potential users and benefactors of the resource. Examples of potential benchmarks include:

- The spawning escapement which produces (on average) a percentage (e.g. 75%) of the maximum recruitment to the river or SMA, i.e., Smax or (Srmax);Footnote 26

- A spawning escapement which produces recruitment at a level where harvesting at the optimum exploitation rate results in a very low probability that the resultant spawning escapement will be at or below the lower benchmark.

Action Step 1.2. Monitor and assess status of populations within SMAs .

Assessment involves the use of various analyses to make predictions about future abundance often based on previous management plans.Footnote 26 Selected populations and SMAs will be assessed by working in closer partnership with users of the resource in the collection of scientific data and assessment of populations taking uncertainty into account as background to advice for management (including conservation when necessary). For wild Atlantic salmon in eastern Canada, however, assessments have been a complex and usually costly task, involving numerous data sources collected on about 75 river systems. Consequently, DFO and Ministère des Ressources naturelles et de la Faune in the province of Québec have used three levels of monitoring programs in index rivers in the assessment of Atlantic salmon:

- Level 1: Research programs involving counts or estimates of the spawning adults, juveniles produced, mature progeny produced (reported in the catch and spawning numbers) from the specific system. These research programs are the most information rich and expensive but provide critical information for management such as productivity and sustainable rates of exploitation (population dynamic values), survival rates for major life history phases (e.g. freshwater and marine survival), and exploitation patterns and rates in fisheries.

- Level 2: Annual surveys of the numbers of spawning salmon in specific streams or habitats within a geographic area. These surveys involve quantitative designs that can be replicated annually to provide consistent indices of spawners between years. The accuracy and precision of the estimates will vary with methodologies and habitats but the essential component is that there is a high degree of confidence that inter-annual trends are accurately assessed. For example, methods may involve in-river counting facilities and operations, mark-recapture programs, and surveys of juvenile production in streams and lakes.

- Level 3: Surveys that are the least expensive and least informative programs but enable the broadest coverage of streams or habitats within a geographic area. These surveys are useful for examining relative abundance of mature salmon and could include indices such as catch per unit of effort within in-river fisheries, juvenile abundance surveys, or indices of adults in tributaries.

Monitoring plans for SMAs will be selected from those existing and, with local partnering (e.g., First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations’ agreements), will be designed to assess the status of populations within the SMAs . The assessment procedures applied will vary between SMAs but monitoring plans for each SMA will be documented. The benchmarks specified for an SMA must be stated in units consistent with the monitoring plan for that SMA in order that the annual status of the SMA can be assessed. An agreed-upon minimum monitoring plan by the government agencies and collaborators will maintain the long-term information fundamental to management of local salmon resources. Each monitoring plan will be peer reviewed to ensure application of appropriate designs and methods to ensure that information management systems have been developed. A key objective of these monitoring plans will be to make certain that data collected are used in a timely way for the provision of advice.

Assessment results for an SMA compared to its two benchmarks will determine the biological status of the SMA. This status determination will help to guide resource management planning and further stock assessment activities. When an SMA is in the Green Zone, a detailed analytical assessment of its biological status will not usually be needed. For an SMA in the Amber Zone, a detailed assessment may be necessary as input to Strategies 2 and 3 below. If the SMA is classified as Red, a detailed assessment will normally be triggered to examine impacts on the SMA of fishing, habitat degradation, and other human factors and to evaluate potential for restoration.

STRATEGY 2: CONSERVATION AND PROTECTION OF ATLANTIC SALMON HABITAT

Healthy Atlantic salmon populations depend on the maintenance of the current productive capacity of salmon habitats, on the rehabilitation of degraded habitats and on the restoration of access to otherwise productive habitats. This can be achieved through the timely review of proposed works or undertakings to prevent changes that can negatively affect fish and existing fish habitat using a risk-based approach, through monitoring for compliance with the habitat provisions of the Fisheries Act and applicable SARA provisions, through monitoring of the effectiveness of measures aimed at achieving “no net loss” of habitat productive capacity, through the assessment of salmon habitat health and status and through the identification of salmon habitat needs and priorities.

The successful conservation and rehabilitation of salmon habitat will require a collaborative approach that integrates the roles and responsibilities of other federal departments and provincial and municipal governments. It also requires the collaboration of key partners such as First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, non-government organizations, watershed groups, universities, industries, etc. Partnering provides mechanisms for information sharing which will lead to the establishment of common priorities that will guide regulatory activities at all levels of government. The collaborative approach also enhances public awareness with regard to Atlantic salmon and its habitat and provides opportunities to promote stewardship of the salmon resource.

The department will strive to progressively implement the following action steps to improve the effectiveness of efforts aimed at conserving, rehabilitating and restoring access to salmon habitat. In collaboration with its partners, the Habitat Management Program will focus on regulatory and compliance responsiveness and effectiveness, strengthen linkages between habitat protection and fish production objectives, and provide guidance on watershed planning initiatives.

Action Step 2.1. Administer habitat protection provisions of the Fisheries Act.

Regulatory reviews

Canada’s fishery resources and fish habitat can be adversely affected by a range of works or undertakings that occur in or near water. DFO has responsibilities for the protection of fish and fish habitat under the habitat provisions of the Fisheries Act (see Objective 2) (and, by extension, SARA). The harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat is prohibited unless authorized by the DFO pursuant to subsection 35(2) of the Fisheries Act. To ensure the effectiveness of conservation and protection efforts, a risk management approach will be applied to ensure that resources are focused on those habitats that are most important to the production of Atlantic salmon. The presence or absence of wild Atlantic salmon as well as the quality and quantity of the habitat will be used as an indicator to inform the level of risk associated with the issuance of an Authorization for the harmful alteration, disruption or destruction of fish habitat resulting from proposed works or undertakings. Furthermore, when assessing the level of risk associated with proposed works or undertakings in or around Atlantic salmon habitat, the specific habitat sensitivities will be considered based on their particular region or SMA.

Conduct habitat compliance and effectiveness monitoring.

Monitoring is an important component of the Habitat Management Program. Monitoring is performed to confirm compliance with regulatory requirements and to assess if the requirements have achieved the desired outcome of habitat conservation and protection. Compliance monitoring aims to ensure that works or undertakings are carried out in compliance with the habitat protection provisions of the Fisheries Act and any SARA provisions that may apply. The Conservation & Protection and Habitat Management programs must collaborate (in accordance with national and regional policies and agreements) in effectively promoting and monitoring compliance with measures protecting salmon habitat, as well in carrying out enforcement actions in relation to serious salmon habitat violations. Effectiveness monitoring will inform the Habitat Management Program as to whether or not measures aimed at achieving the objective of “no net loss” of habitat productive capacity are successful.

Compliance and effectiveness monitoring of works or undertakings presenting risks to Atlantic salmon and its habitat will be conducted in collaboration with science, proponents, First Nations and other Aboriginal organizations, and other stakeholders. The information gathered will be used to ensure the continuous improvement in the conservation and protection of wild Atlantic salmon habitat.

Action Step 2.2 Monitor and assess habitat health and status.