Final evaluation report

Evaluation of Aboriginal Programs: Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) and Aboriginal Aquatic Resource and Oceans Management

(AAROM)

March 4 2019

Table of Contents

- 1.0 Program Context

- 2.0 Evaluation Context

- 3.0 Methodology and Limitations

- 4.0 Evaluation Findings

- 5.0 Recommendations

- Management Action Plan

NOTE: The Evaluation of Aboriginal Programs: AFS and AAROM has an alternative report format that uses graphics and visuals, which is available in pdf format PDF version.

1.0 Program Context

This evaluation examined two Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) grants and contributions (Gs&Cs) programs: the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) and the Aboriginal Aquatic Resource and Oceans Management (AAROM) program.

The AFS was developed in 1992 in response to the 1990 Sparrow Supreme Court decision, to provide a framework for Aboriginal fishing for food, social and ceremonial (FSC) purposes under the authority of communal licences issued under the Fisheries Act. AFS also helps Indigenous communities build management and scientific capacity, so that they can meaningfully participate in the management of FSC fisheries.

The AAROM program, created in 2004, provides funding to Indigenous organizations (AAROM organizations1) for skilled personnel to undertake scientific research activities to support ecosystem-based management and to hire staff to participate in advisory and decision-making processes related to aquatic resources and oceans management. In addition, AAROM organizations are designed to serve as a platform for Indigenous communities to access other programs within DFO and interdepartmentally.

There were 138 AFS recipients and 37 AAROM recipients between 2013-14 and 2017-18.

Figure 1 is a map of Canada that illustrates the number of AFS and AAROM recipients by DFO region (6 regions plus the National Capital Region). Circles with the number of AFS and AAROM recipients have been placed on the map to show the number of contribution recipients in each of the regions. • The Pacific Region includes all of British Columbia and the majority of Yukon, with the exception of the northern most portion bordering the Beaufort Sea. In the Pacific Region, there are 21 AAROM organizations and 88 AFS recipients. • The Central and Arctic Region includes the northern most portion of Yukon, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario. In the Central and Arctic Region, there are 3 AAROM organizations and 4 AFS recipients. • In the National Capital Region, there is 1 AAROM organization and 1 AFS recipient. • The Quebec Region, which corresponds to the province limits, has 3 AAROM organizations and 10 AFS recipients. • The Gulf Region includes the waters of the Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence at the eastern coast of New Brunswick, the Northumberland Strait coast of Nova Scotia and Western Cape Breton Island, as well as Prince Edward Island. In the Gulf region there are 2 AAROM bodies and 16 AFS recipients. • The Maritimes Region includes the Southern part of New Brunswick and the Southern part of Nova Scotia. In the Maritimes Region, there are 6 AAROM organizations and 15 AFS recipients. • The Newfoundland and Labrador region includes Newfoundland and Labrador. In the Newfoundland and Labrador Region, there is 1 AAROM organization and 4 AFS recipients.

In areas where DFO manages the fisheries and where land claim agreements have not been signed, the Department seeks to fulfill its mandate – to manage fisheries and fish habitat – in a manner consistent with the protection provided to existing Aboriginal and treaty rights by Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

Highlights of the AFS and AAROM Programs

Figure 2 is a timeline showing the highlights of the AFS and AAROM programs since they began. From left to right, we have: • 1990: The Sparrow Supreme Court decision takes effect; • 1992: DFO launches the AFS program; • 1999: AFS review; • 2004: DFO launches the AAROM program in response to the AFS review; • 2009: Programs are evaluated; • 2013: Programs are evaluated; and • 2018: Indigenous Program Review and AFS/AAROM Evaluation.

The Indigenous Programs Branch within the Indigenous Affairs and Reconciliation Directorate serves to build and maintain strong relations with Indigenous groups, establish and/or enhance collaborative management and promote fisheries-related economic opportunities for Indigenous communities, all of which are instrumental to maintaining a stable fisheries management regime with common and transparent rules for all.

Indigenous Program Review

The Indigenous Program Review, covering all the programs in the Indigenous Programs Branch, was conducted and overseen by the National Indigenous Fisheries Institute during the course of the evaluation. The review focused on “the technical examination of the function and evolution of each program to see what may need to change or be improved to maximize the benefits to Indigenous Peoples and communities across Canada.”[2]

The Indigenous Program Review included the following phases:

Launch:

- Document review, including evaluations, audits, etc. (166 source documents)

- Joint announcement and discussion papers published online (October 2017)

Phase 1:

- Workshops and plenaries with Indigenous AAROM organizations (October 2017 to February 2018)

- First report released including recommendations related to AAROM (May 2018)

Phase 2:

- Workshops and plenaries on AFS and on Aboriginal Fishery Guardians (May 2018 to January 2019)

- Final report to be published in winter 2019 and will include recommendations

2.0 Evaluation Context

The evaluation was designed to address the needs identified by senior management, taking into consideration the Indigenous Program Review, requirements of the Financial Administration Act and the Policy on Results. The evaluation covered the period from 2013-14 to 2017-18 and examined the , effectiveness and efficiency of the AFS and AAROM programs.

Given the Indigenous Program Review at the time of the planning and conduct of this evaluation, the core questions were determined based on the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016), the Financial Administration Act (FAA), a review of key program documents, results from preliminary discussions with senior management and program staff, and findings from previous evaluation reports.

Key aspects identified by the evaluation

- To respond to information needs;

- To avoid duplication of the Indigenous Program Review, certain components of AFS were scoped out (Fishery Guardian Program, Allocation Transfer Program and the Aboriginal Funds for Species at Risk Program);

- Interviewee fatigue;

- Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) including gender, culture, geography, etc.

Evaluation core questions

- Is there a continued need for the AFS and AAROM programs?

- To what extent are AFS and AAROM contributing to capacity building?

- To what extent are AFS and AAROM activities, structures and processes appropriate to support capacity building?

- To what extent are AFS and AAROM activities consistently tracked using the Aboriginal Programs and Governance Information System (APGIS)?

All DFO regions were included: the National Capital Region (NCR); Newfoundland and Labrador (N&L); Maritimes; Gulf; Quebec; Central and Arctic (C&A); and Pacific.

Launched in February 2018, the evaluation concluded in February 2019. The evaluation report, summary and Management Action Plan was presented at the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee (PMEC) meeting in March 2019.

AFS and AAROM were last evaluated in 2013-14 as part of the Evaluation of the Aboriginal Strategies and Governance Program.

3.0 Methodology and Limitations

3.1 Methodology

To produce useful, valid and meaningful findings, the evaluation used a mixed methods approach, where both qualitative and quantitative data were collected. Triangulation was used extensively across all lines of evidence to corroborate findings.

Key Informant Interviews

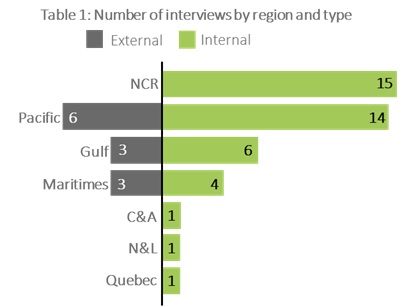

A total of 54 interviews were conducted: 42 interviews with DFO employees and 12 interviews with program recipients.

Figure 3 contains a back-to-back chart, which illustrates the number of internal and external interviews by DFO region that were conducted during the evaluation. The first bar graph on the left shows the number of interviews conducted externally by DFO Region: • 0 for the NCR; • 6 in the Pacific Region; • 3 in the Gulf Region; • 3 in the Maritimes Region; • 0 in the Central & Arctic Region (C&A); • 0 in the Newfoundland & Labrador Region (N&L); and • 0 in the Quebec Region. The second bar graph on the right shows the number of internal interviews conducted internally by DFO Region: • 15 in the National Capital Region; • 14 in the Pacific Region; • 6 in the Gulf Region; • 4 in the Maritimes Region; • 1 in the Central & Arctic Region; • 1 in the Newfoundland & Labrador Region; and • 1 in the Quebec Region.

Financial & Administrative Data

Administrative data was extracted from the Aboriginal Programs and Governance Information System (APGIS), which is the application used by the programs to manage contribution agreements. The APGIS data extracted for analysis included: payment allocation histories, year end reporting, recorded interactions, and Recipient Capacity Assessment Tool (RCAT) scores.

The information contained in APGIS for a sample of 23 AFS recipients was reviewed. The sample was selected from the total of 138 AFS recipients and took into consideration the following factors: regional representation, a variety of capacity rankings, funding allocations, the length of time the recipient has been involved in the program, and the types of activities in which recipients participate.

Financial information provided by the Chief Financial Officer (Vote 1 and Vote 10) was analyzed.

Document Review

A document review was conducted to gather insight into the programs and included: Treasury Board Submissions, Integrated Aboriginal Policy Framework, program documentation, recipient documentation, and National Indigenous Fisheries Institute reports.

Site Visits

Two site visits to the Maritimes and Gulf regions were completed in October 2018 to conduct interviews with recipients, program staff and other DFO employees with involvement in the program(s).

Survey

An online survey was used to investigate the efficiency and economy of the programs by gathering information on the functionality of APGIS as an application, and determining the level of standardization across the regions and users.

The survey was designed to answer the following questions:

- The extent to which AFS and AAROM contribution agreements are coordinated and standardized;

- The extent to which APGIS is tracking AFS and AAROM results and interactions;

- The extent to which information in APGIS is used for decision-making; and

- To determine the strengths and limitations of APGIS.

The survey was made available online to 589 APGIS users[3] and 101 completed survey responses were received. The survey was administered between October 31 and December 3, 2018. Of the 101 respondents, 96% were DFO staff and 4% were Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) staff.

Figure 4 is a bar graph representing the percentage of APGIS survey respondents by DFO Region: • 31% in the Gulf Region; • 30% in the Pacific Region; • 20% in the National Capital Region; • 9% in the Maritimes Region; • 4% in the Central and Arctic Region; • 3% in the Quebec Region; and • 3% in the Newfoundland and Labrador Region.

3.2 Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Although the evaluation encountered some challenges, methodological limitations were mitigated, where possible, through the use of multiple lines of evidence and the triangulation of data. This approach was taken to establish the reliability and validity of the findings and to ensure that conclusions and recommendations were based on objective and documented evidence.

Survey

To mitigate possible limitations with the user list, an introductory e-mail was sent to all 759 employees with access to APGIS. This allowed the evaluation team to identify a possible 589 users who were sent the survey. Survey results were analysed from 101 survey respondents (17% response rate) and were collected on December 4, 2018. There is very little management of the APGIS user list and, as such, of the 589 who were sent the survey, the evaluators are unsure how many are active users within the system. The majority of survey respondents report using APGIS primarily for AFS and AAROM program-related work.

Interviews

Interviews with external AFS recipients were very limited given the ongoing interviews conducted as part of the Indigenous Program Review and the concern of interview fatigue. To mitigate, APGIS administrative data for a sample of AFS recipients was reviewed, including availability of Year End Reports, interactions with program staff, RCAT scores and funding allocations. Additionally, some AAROM interviewees are also AFS recipients and were able to speak to their experience of each program.

Aboriginal Programs and Governance Information System (APGIS)

APGIS is not consistently used between regions or even within regions. To mitigate, APGIS data was triangulated with other sources of evidence from interviews and the survey.

4.0 Evaluation Findings

4.1 Continued Need for AFS and AAROM

Finding: There is a continued need for AFS and AAROM, and both programs contribute to departmental results. However, funding has limited the ability of the programs to fund other recipient activities in order to increase their involvement in collaborative management.

The programs do not have a funding allocation process in place to determine the amount of funding allocated to recipients. Funding allocations were constant year after year and are not based on the performance of groups. Although funding has remained largely constant in terms of dollar value, the actual worth of the funding has decreased due to inflation. Both AFS and AAROM have seen their funding increased as a result of Budget 2017.

AFS budgets and expenditures are a roll-up of Votes 1 and 10. Over the five-year period, AFS actual expenditures fluctuated by $1.9M (Table 3)[4].

Figure 5 is a line graph representing AFS budgets and expenditures over the period of 2013-14 to 2017-18. The AFS budgets and expenditures are a roll-up of Votes 1 and 10. The first of two lines shows the progression of AFS Budgets* over the 5-year period as follows: • $25.2M in 2013-14; • $25.5M in 2014-15; • $24.9M in 2015-16; • $24.6M in 2016-17; and • $26.5M in 2017-18. The second line shows the progression of AFS Expenditures* over the 5-year period as follows: • $25.1M in 2013-14; • $25.7M in 2014-15; • $25.0M in 2015-16; • $24.5M in 2016-17; and • $26.2M in 2017-18. *Whilst figures depicted in the graph are exact, they have been rounded to the nearest 100k for the purpose of the text description.

Notes about the graph:

- Well-aligned budgets and expenditures.

- Actual expenditures fluctuate by $1.9M over the period 2013-14 to 2017-18.

Evidence indicates that there is a continued need for AFS

- AFS responds to the Sparrow Supreme Court decision.

- There is a continued need for stock assessment and catch-monitoring as these activities allow recipients to participate in decision-making processes used for aquatic resource and oceans management.

AAROM budgets and expenditures are a roll-up of Votes 1 and 10 for the five-year period. Although it appears in Table 4 that AAROM budgets and expenditures have increased, AAROM actual budgets and expenditures have remained largely constant. AAROM’s funding increased as a result of Budget 2017 and from other DFO programs (e.g., Oceans Management) funding being delivered through the AAROM program using AAROM as a platform[5].

Figure 6 is a line graph representing AAROM budgets and expenditures over the period of 2013-14 to 2017-18. The AAROM budgets and expenditures are a roll up of Votes 1 and 10. The first of two lines shows the progression of AAROM budgets* over the 5-year period as follows: • $15.9 M in 2013-14; • $16.6 M in 2014-15; • $16.4 M in 2015-16; • $19.3 M in 2016-17; and • $21.1 M in 2017-18. The second line shows the progression of AAROM expenditures* over the 5-year period as follows: • $16.1 M in 2013-14; • $16.6 M in 2014-15; • $16.4 M in 2015-16; • $19.0 M in 2016-17; and • $21.2 M in 2017-18. * Whilst figures depicted in the graph are exact, they have been rounded to the nearest 100k for the purpose of the text description.

Notes about the graph:

- Aside from Budget 2017 funding, one explanation for the increase between 2015-16 and 2017-18 is the increased use of AAROM as a platform.

- Financial information does not distinguish between contributions made by the AAROM program from those made by AAROM as a platform, therefore, it was not possible to get the expenditures for AAROM alone, nor to identify other DFO programs using AAROM as a platform.

Evidence indicates that there is a continued need for AAROM

- AAROM organizations have built technical expertise and capacity which enables them to work with DFO.

- AAROM organizations are recognized for their expertise and could be further involved in collaborative management and used by other programs within DFO and by other departments (i.e., AAROM as a platform5).

However, the possibility of increasing AAROM activities through the program alone is limited by the funding of the program.

Other Indigenous programs complement AFS and AAROM. For example, the Pacific Integrated Commercial Fisheries Initiative has similar capacity-building outcomes to AAROM, but focuses on commercial fisheries while AAROM does not.

AFS and AAROM contribute to DFO’s Fisheries Core Responsibility, mandate letter priority of relationship-building with Indigenous Peoples as well as to Government of Canada priorities (Indigenous People, Diverse and Inclusive Canada, Jobs and Innovation and Environment and Climate Change). Program data for both AFS and AAROM contribute to two departmental results.

1) Improving relationships with and outcomes for Indigenous people. Both programs are on track to meet their targets regarding the number of Indigenous jobs in aquatic ecosystems and oceans science. For example, through AFS and AAROM, skilled personnel (e.g., professional, administrative and technical) have been hired, however, Indigenous jobs are not exclusively filled by Indigenous people.

Percentage of the target reached by AFS and AAROM related to the number of Indigenous people employed in aquatic ecosystems and oceans science:

Figure 7 shows two pie donuts detailing the percentage of the target reached by AFS and AAROM related to the number of Indigenous People employed in aquatic ecosystems and oceans science: • AFS: 90%; and • AAROM: 78%.

2) An increased number of Indigenous groups participating in collaborative management activities. Both programs are on track to meet their targets regarding the eligible Indigenous communities represented by collaborative fisheries management agreements and watershed-level management bodies.

Target reached by AFS and AAROM related to the percentage of total recipients represented in collaborative management agreements:

Figure 8 shows two pie donuts detailing the percentage of the target reached by AFS and AAROM related to the percentage of total recipients represented in collaborative management agreements: • AFS: 91%; and • AAROM: 89%.

4.2 Capacity Building

4.2.1 Capacity Building: What Is It?

Finding: Capacity building has not been clearly defined by the programs and was interpreted differently by all interviewees. Although each recipient is unique, capacity has been built within AAROM organizations, and with some AFS recipients. Skills development and technical expertise are most commonly understood as capacity building activities.

Both AAROM and AFS support capacity building. The interpretation of capacity building by key informants varied and is summarized below. The size of the words are determined by the frequency with which they were mentioned by interviewees[6].

| AAROM Internal and external interviewees define capacity building as developing skills, acquiring technical expertise and employing staff in the AAROM organization. AAROM representatives indicate that the capacity of their AAROM organization has increased as a result of the program, but they have expressed a need to expand their capacity beyond its current state if their involvement in the management of fisheries and aquatic resources is to expand.[7] |

Figure 9 shows a word cloud summarizing the interpretation of capacity building by AAROM key informants. The size of the words vary which indicates the frequency with which they were mentioned. From largest to smallest and from top to bottom: • Skills development; • AAROM staff; • Technical expertise; • Liaising with DFO; • Equipment; • Training youth; • Fisheries management; and • Community involvement."> |

| AFS Capacity building for AFS includes developing skills, acquiring technical expertise and having administrative functionality. The program supports these areas of capacity building for AFS recipients, however, key informant interviews suggest that capacity has not been sufficiently developed to address ongoing needs. |

Figure 10 shows a word cloud summarizing the interpretation of capacity building by AFS key informants. The size of the words vary which indicates the frequency with which they were mentioned. From largest to smallest and from top to bottom: • Skills development; • Technical Expertise; • Administration; • Fisheries management; • Community involvement; • Having fisheries staff; • Stability; and • Equipment. |

4.2.2 Factors that Contribute to Capacity Building

Finding: Given the absence of a clear definition of capacity building, there are a variety of factors that were identified as contributing to capacity building in AAROM organizations or by AFS recipients. The common factors between the programs include available funding, training and the importance of working with others.

AAROM

Key informants identified six main factors that support/help capacity building in AAROM organizations:

|

Funding: AAROM funding and other sources |

|

Multi-year Agreements: Ongoing funding to hire and retain staff |

|

Networking: Partnering* |

|

DFO support: DFO provides training and loans equipment |

|

AAROM staff: AAROM organization have staff with technical expertise |

|

Community training: Training available to community members |

* Federal, Provincial, Territorial and other Non-Governmental Organizations

AFS

Key informants identified four main factors that support/help capacity building for AFS recipients:

|

Funding: AFS funding and financial support from Chief/Band |

|

Relationship with DFO: Maintaining a good working relationship |

|

Community training: Training available to community |

|

Support from local leadership: Having the support from Chief/Band |

4.2.3 Gaps in Capacity Building

Finding: Although there are a number of factors that hinder capacity building, lack of funding and skilled personnel are the greatest challenges to capacity building. Further, the gaps that were identified included the incorporation of Indigenous Traditional Knowledge (ITK) and communication between recipients and DFO employees.

Factors that hinder capacity building

|

Figure 11 shows a word cloud summarizing the factors that hinder capacity building. The size of the words vary which indicates the frequency with which they were mentioned. From largest to smallest and from top to bottom: • Lack of funding; • Lack of skilled personnel; • Stagnant funding; • Staff turnover; • Community politics; and • Remote location."> |

Incorporating Indigenous Traditional Knowledge

- According to foundational program documentation, integration of ITK is listed as an eligible activity for both of the programs.

- The previous evaluation in 2013-14 found that advancements were being made in incorporating ITK as it was increasingly understood and respected at that time. These advancements were in large part due to improved relationships which were the result of Joint Management and Technical Committees that provided a helpful forum for DFO and Indigenous organizations to work together[8]. Since then, these committees and other working groups have dissolved. Interviewees suggested that more could be done to incorporate ITK into discussions between recipients and DFO employees to inform decision-making. Some AFS and AAROM working groups have recently been established and may contribute to the integration of ITK going forward.

DFO Employees could improve communication by increasing their cultural awareness and use of plain language

- Interviewees suggested a need for some DFO employees to improve their understanding of recipients’ culture when interacting with them.

- Additionally, at times, it was noted that DFO employees could be more sensitive to existing language barriers. For example, an individual may know the name of a fish in their own native language, but not in English or French.

4.2.4 Result of Capacity Building

Finding: The evaluation determined that Indigenous organizations are participating in activities and processes related to the management of fisheries and aquatic resources as a result of their involvement with AFS and AAROM programs, but the extent of this participation cannot be measured.

Success stories the evaluation team heard…

- On the West coast, a First Nation community expanded their shellfish operation. They have developed a plan for continued expansion and inclusion of other species.

- In the Maritimes, an AAROM organization started training and engaging youth from its various communities by using educational modules and games.

- In Quebec, AFS helped First Nations to receive the training and equipment they needed to start fishing groundfish. This resulted in the Nations growing their groundfish revenue from 0% to 20% in two years.

|

There is very limited performance measurement information available for key aspects of the program, e.g., capacity building, integration of ITK, collaborative management, etc., making it difficult to measure results since data are not collected. Therefore, the evaluation was unable to determine to what extent recipient capacity has changed over the scope of the evaluation. The lack of data is a recurring finding from the last two evaluations[9], [10] which also limited the ability of those evaluations to fully assess the programs. |

4.3 Tools used by the Programs

4.3.1 Tools used by the Programs

The AFS and AAROM programs have two tools at their disposal: the Recipient Capacity Assessment Tool to measure contribution agreement risk, and the Aboriginal Programs and Governance Information System which is primarily used to monitor contribution agreements and associated payments.

Recipient Capacity Assessment Tool (RCAT)[11]

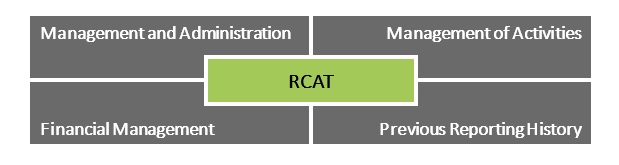

The RCAT is a contribution agreement assessment tool designed to measure risk and determine the appropriate conditions to be included in contribution agreements. This tool is linked solely to a recipient’s administrative capacity. The four measures that are used to determine the RCAT score are:

Figure 12 shows a large rectangle with four equal quadrants representing the four measures that are used to determine an RCAT score. The four measures clockwise from the top left are: • Management and Administration; • Management of Activities; • Previous Reporting History; and • Financial Management.">

Aboriginal Programs and Governance Information System (APGIS)11

APGIS is defined as a national information system to help DFO-CCG employees administer and manage Aboriginal Programs’ transfer payments. The application was designed, and introduced to employees in 2011, to meet three major objectives:

- Client Relationship Management

- Transfer Payment Management

- Results and Performance

4.3.2 Recipient Capacity Assessment Tool (RCAT)

Finding: RCAT scores, as a measure of AFS and AAROM recipients’ capacity, reflect administrative abilities and do not measure technical capacity. RCAT scores have shown slow growth, and there is an opportunity to improve the tool by reviewing the assessment questions.

RCAT scores of less than 33 out of a possible 40 result in a Standard agreement, which is usually for a duration of one year. Recipients scoring 33 or more receive an Enhanced agreement. Enhanced groups are eligible for multi-year agreements which benefit from reduced reporting requirements.

While contribution agreements describe the activities to be undertaken by a recipient in detail (e.g., river monitoring, fisheries management, Geographic Information System (GIS) and mapping, etc.), administrative data analysis revealed that the RCAT does not measure the results of these activities, but rather the ability of the recipients to report on their activities. Recipients are responsible for progress and year end reporting, which can include financial and narrative summaries of all activities.

Furthermore, RCAT results are not consistently discussed with recipients to provide them the opportunity to understand how to improve their score.

RCATS are reviewed yearly

Although recipients’ RCATs are reviewed yearly using a capacity assessment questionnaire, the review of administrative data demonstrated that RCAT scores are often cloned from the previous year. Interviews suggest that reviewing RCAT assessment questions would improve the tool.

Slow RCAT growth

Data analysis of the AFS sample (23 recipients) and all AAROM organizations show an average RCAT annual increase of 1% and 5% respectively. This means that on average 1% of the AFS sample recipients and 5% of all AAROM recipients improved their administrative reporting capacity over the last five years.

RCATs do not measure technical capacity

Although contribution agreements detail technical activities to be undertaken by recipients over the upcoming fiscal year, no measure exists to determine recipients’ technical capacity growth.

4.3.3 AFS/AAROM and APGIS

Finding: While information contained within APGIS is found to be beneficial to manage the contribution agreements between DFO and AFS/AAROM recipients, there is opportunity for improvement in terms of the training and clear guidance on the expected information to be captured in APGIS

The evaluation did not assess the capability of APGIS as a tool. Instead, the evaluation focused on the extent to which the information related to the activities of AFS and AAROM was consistently tracked in APGIS.

While signed contribution agreements for AFS and AAROM are tracked consistently and in a timely manner in APGIS, the AAROM financial information in APGIS does not align with corporate finance output.

Figure 13 shows the progression of contribution agreements from being ratified to being paid out. Three arrows of increasing size from left to right detail: • Contribution Agreements are made available in APGIS; • Associated funding is authorized in APGIS; and • Corporate Finance processes contribution payments. Additional text under the smallest arrow on the left reads: Contribution Agreements must be authorized in APGIS before payments can be authorized. Additional text under the largest arrow on the right reads: Contribution payment dates are manually entered into APGIS by Chief Financial Officer staff.">

Although APGIS contributes to managing the work related to contribution agreements, APGIS users would benefit from clear guidelines on expected information to be captured in APGIS for consistent data management and standardization.

| Over the period covered by the evaluation, APGIS training has been offered through 20+ events across the country and email support is always available. Despite these efforts, 61% of survey respondents reported having received limited to no formal training, and 64% say their greatest source of support was from colleagues. |

58% of survey respondents agree that there is no clear guidance on what information to enter into APGIS."> |

Finding: Information, performance data and interactions between recipients and AFS and AAROM programs are inconsistently captured in APGIS.

Client relationship and performance data is stored in various locations and formats.

- Inconsistent Data Management and Lack of Consistency

- Sixty two percent (62%) of survey respondents report that interactions with recipients (e-mails, meetings, telephone discussions, etc.) are inconsistently captured in APGIS.

- Fifty percent (50%) of survey respondents indicate using alternative methods to track results and interactions, including Excel spreadsheets, the shared network, employees’ desktop, e-mails and another database.

Although information stored in APGIS can help inform decision-making, AFS and AAROM do not use APGIS to capture and monitor all results and performance information.

- Helps inform: Information stored in APGIS can help to answer questions, inform briefing notes, memos, letters of consultation and ministerial correspondence. For example, APGIS helps re-profile funds when funding becomes available.

- Not all results data are available: Some departmental results data is tracked using APGIS (e.g., number of contribution agreements and communities), however economic opportunities created by AFS/AAROM are tracked using separate Excel spreadsheets.

- No centralized performance information: A ‘Performance Indicators’ feature exists in APGIS, however, the programs are not storing their performance information in this central space. Therefore, performance information is not easily accessible.

4.3.4 How AFS and AAROM use APGIS to manage their information

The programs use APGIS to monitor contribution agreements and manage corresponding payments. Key informants and survey respondents consider information stored within APGIS recipient profiles useful, and 50% of survey respondents agree that information stored in APGIS provides a full spectrum of funding history and activities associated with the agreements.

Other than contribution agreements and associated funding information which are mandatory, some information is not stored in APGIS or is stored inconsistently. Some factors that contribute to these challenges are:

- No clear guidelines on expected information to be captured, and the level of detail to be included in APGIS results in users being selective about which information to store in APGIS. Fifty three percent (53%) of survey respondents report that contribution agreements do not contain the same level of detail.

- Some users do not know how to use the system, either because they have not received APGIS training or they have not been made aware of system upgrades.

- Locating specific documents within APGIS is difficult, as these can be buried as e-mail attachments within APGIS. For example, on average, 37%[12] of year-end reports of the AFS sample were unavailable in APGIS.

- Due to IT infrastructure challenges in some locations, there are issues loading and connecting to APGIS, especially in the regions (i.e., where APGIS is accessed through Citrix and in remote areas).

In addition, users have difficulty retrieving stored information using the search function in APGIS. For example, a user cannot use the search box of APGIS for the name of an individual or by vessel identifier.

Figure 14 shows some of the identity factors that are considered when talking about Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+). GBA+ is an analytical tool, process, or product used to assess the potential impacts of policies, programs, services, and other initiatives on diverse groups of women and men, taking into account gender and other identity factors. This figure illustrates some of the factors which can intersect with sex and gender. Six oblong shapes of differing colors overlap and fan out. Each oblong has two identity factors written on it. The top oblong has “sex and gender” written in a larger font. Starting below sex and gender and going clockwise, the additional identities identified are: geography, culture, income, sexual orientation, education, ethnicity, ability, age, religion and language. AND a box that reads GBA+ Opportunity The ‘Proactive Disclosure’ feature in APGIS provides an opportunity to collect Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) data going forward.">

4.4 Coordination

4.4.1 Coordination

Finding: Greater coordination is needed as limited interaction occurs between AFS/AAROM programs and other DFO programs resulting in missed opportunities.

Greater coordination is needed

- Evidence demonstrates that limited interaction occurs between AFS/AAROM and other DFO programs (e.g., Science, Species at Risk, Fisheries Protection Program, Oceans Management, Conservation and Protection, Canadian Coast Guard, etc.) resulting in missed opportunities.

- Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) processes undertaken by DFO science groups were raised as an example where greater coordination would allow better integration of ITK and data gathered by program recipients within DFO processes.

- Evidence also suggests that other federal departments (e.g., Transport Canada, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada/Indigenous Services Canada, Natural Resources Canada, etc.) are not using AAROM as a platform.

Greater coordination could…

- Reduce programs working in silos

- Allow sharing of best practices

- Improve the development of recipients’ annual work plans by receiving input from other DFO-CCG programs

- Improve communications with communities

Examples of best practices

- Interviewees suggested that the new working groups being created (e.g. Fisheries Guardians, AFS and AAROM) were sought as a solution to bridging the coordination gap.

- A regional calendar on Consultation SharePoint, used in the Pacific Region, provides a snapshot of consultations across different groups within DFO. It allows DFO employees to see the different consultations happening which results in greater coordination, when possible.

4.4.2 Coordination and Reporting

Finding: Multi-year contribution agreements, accessibility of tools and guidelines online, and providing recipients with access to APGIS to upload reports, data, etc. were raised as potential improvements to coordination and reporting.

Figure 15 illustrates the contribution process cycle which includes four components that are interconnected by single direction arows. Starting from the top and going clockwise, the four elements are: Contribution Agreement, Funding allocation, Funding to recipients and Reports

Challenges with the reporting

- AAROM representatives interviewed mentioned that Gs&Cs can be burdensome for Indigenous groups, as reporting requirements are different from one G&C to another.

- There is a substantial reporting workload on the recipients that receive different Gs&Cs (e.g., Oceans Management, Habitat Stewardship Program, Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk, Coastal Restoration Fund).

- Groups that are eligible for multi-year agreements benefit from reduced reporting requirements.

Challenges with the business cycle

- Interviewees mentioned that the government calendar does not align with the activity cycle of groups. For example, final reports are requested during the fishing season.

- Recipients interviewed mentioned that the time it takes for their contribution agreement to be signed in order to receive their first installment creates challenges for them. For example, groups have to cash manage over the summer months and in some instances activities did not occur. Efforts have been made by DFO employees to initiate the process to develop annual work plans earlier in order to have signed agreements in place at the beginning of the fiscal year.

Examples of potential improvements

- Tools and guidelines online

- Reporting could be streamlined and standardized

- Recipients could have an access to APGIS to upload reports

- Contribution Agreements could be signed earlier in the year

- Multi-year agreements (e.g., 3 to 5 year agreements)

5.0 Recommendations

|

Recommendation #1: Capacity Building |

|||

| Rationale: There is currently no common understanding of capacity building for AFS or AAROM among program recipients and program staff. Moreover, the availability of high quality and reliable data are needed to ensure that AFS and AAROM measure the advancement of the capacity of recipients. The current recipient capacity assessment tool reflects the administrative abilities of recipients but, does not measure the technical capacity nor if results have been achieved. | |||

|

Recommendation #2: Coordination |

|||

| Rationale: Limited interaction between AFS/AAROM and other DFO-CCG programs result in missed opportunities. Greater coordination could reduce programs working in silos; allow for sharing of best practices; and improve the development of recipients’ annual work plans by receiving input from other DFO-CCG programs. Moreover, improving coordination would also benefit recipients who are often receiving funding from multiple programs. | |||

|

Recommendation #3: Consistency of data |

|||

| Rationale: As was found by this evaluation and the previous two, performance measurement data is not being collected by the programs; only anecdotal information is available to measure how the programs are achieving their expected results. In addition, information available in APGIS is inconsistent within and across regions, due in part to a lack of clear guidance related to the information that needs to be captured in APGIS and limited training having been received by users. | |||

Management Action Plan

| Recommendation 1 | |||

| Recommendation 1: Capacity Building It is recommended that the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy, define capacity building for AFS and AAROM and also develop tools to measure capacity building to demonstrate the progression of recipient’s capacity over time. Rationale: There is currently no common understanding of capacity building for AFS or AAROM among program recipients and program staff. Moreover, the availability of high quality and reliable data are needed to ensure that AFS and AAROM measure the advancement of the capacity of recipients. The current recipient capacity assessment tool reflects the administrative abilities of recipients but, does not measure the technical capacity nor if results have been achieved. |

|||

| Strategy | |||

| The Indigenous Programs Branch, within the Indigenous Affairs and Reconciliation Directorate, working with Indigenous program participants and experts, will co-develop and implement capacity assessment and development models and tools for the AAROM and AFS programs. Given the stepwise and multiyear approach already being taken to review and renew these program (informed by a Budget 2017 commitments and Indigenous Program Review (IPR)), this strategy will be implemented incrementally, starting with the AAROM program and then followed by AFS. AAROM renewal has begun (e.g., IPR recommendations were received in May 2018 and implementation of a renewed program is ramping up, including the launch of new co-development, co-design and co-delivery structures with AAROM departments that can facilitate the implementation of this strategy). IPR recommendations on AFS have yet to be received (expected Spring 2019), are expected to be more transformative, and will take longer to design and implement. Work conducted and products produced for the AAROM program will also help inform the process and products for AFS. | |||

| Management Action | Due Date (by end of month) | Status Update: Completed / On Target / Reason for Change in Due Date | Output |

| AAROM & AFS – Develop and add commitment to co-develop capacity development definitions, models and tools in the multi-year Action Plan that will be developed to respond to the final Indigenous Program Review Report | August 2019 | ||

| AAROM – Produce a draft outline of potential capacity development definitions, assessment elements and tools (general and AAROM specific) and share with AAROM departments in advance of National AAROM meeting | September 2019 | ||

| AAROM – Hold working session at the National AAROM meeting to review and receive input on the draft outline and co-design a process for co-development of final definitions, tools and implementation plans (general and AAROM specific) | November 2019 | ||

| AAROM – Launch co-development activities and working group to develop the final definitions, tools and implementation plans (overall and AAROM specific) and engage AAROM departments and DFO sectors and federal Departments as required. | November 2019 | ||

| AAROM – Share final definitions, tools and implementation plans (overall and AAROM specific) with AAROM departments prior to the annual National AAROM meeting. | September 2020 | ||

| AFS – Begin planning and seek guidance of AAROM working group on approach to development of capacity assessment definitions, models and tools for AFS. | October 2020 | ||

| AAROM – Receive final input from AAROM departments at the Annual AAROM Meeting on the final definitions, tools and implementation plan for AAROM and for collaborative programs overall | November 2020 | ||

| AAROM – Finalize definitions, tools and implementation plans for AAROM and interim for collaborative programs overall | February 2021 | ||

| AFS – Produce a draft outline of potential capacity development definitions, assessment elements and tools for the AFS program and share with a co-design working group. | March 2021 | ||

| AAROM – Begin to implement standard definitions, models, and tools for the AAROM program | April 2021 | ||

| AFS – Targeted engagement on draft AFS capacity definitions, models and tools | September 2021 | ||

| AFS – Share final definitions, tools and implementation plans for AFS. | November 2021 | ||

| AFS – Targeted engagement to receive final input on AFS capacity development definitions, models and tools | January 2022 | ||

| AFS – Finalize definitions, tools and implementation plans for AFS program. | February 2022 | ||

| AFS – Begin to implement standard definitions, models and tools for the AFS program. | April 2022 | ||

| Recommendation 2 | |||

| Recommendation 2: Coordination It is recommended that the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy, establish formalized coordination between AFS/AAROM and other DFO-CCG programs that are or could be involved with AFS/AAROM recipients. Rationale: Limited interaction between AFS/AAROM and other DFO-CCG programs result in missed opportunities. Greater coordination could reduce programs working in silos; allow for sharing of best practices; and improve the development of recipients’ annual work plans by receiving input from other DFO-CCG programs. Moreover, improving coordination would also benefit recipients who are often receiving funding from multiple programs. |

|||

| Strategy | |||

| The Indigenous Programs Branch, within the Indigenous Affairs and Reconciliation Directorate, will develop/co-develop tools, guidance and structures that can improve cooperation and coordination between federal programs and Indigenous organizations participating in the AFS and AAROM programs. Actions will focus on internal coordination/outreach products and activities, along with working with program participants in the co-development of standard information products and guidelines for potential partners. The Branch will also continue to support the development of the DFO Grants and Contributions Community of Practice (led by CFO sector) and the building of capacity within other DFO sectors including guidance on working with Indigenous proponents, including AAROM and AFS recipients. | |||

| Management Action | Due Date (by end of month) | Status Update: Completed / On Target / Reason for Change in Due Date | Output |

| Develop and add commitment to develop/co-develop tools and processes to support increased cooperation and coordination between federal programs and AAROM departments and AFS capacity within the multi-year Action Plan that will be developed to respond to the final Indigenous Program Review Report | August 2019 | ||

| Develop and start implementing interim internal outreach strategy for federal programs/initiatives to promote the AAROM and AFS programs and opportunities for increased coordination (e.g., briefings, info sharing sessions, program inventory, etc.) | September 2019 | ||

| Hold working session at the National AAROM meeting to review and continue to co-develop draft AAROM information and guidance materials for federal and other partners (as part of the AAROM Marketing and Partnership Tool Kit) | November 2019 | ||

| Develop standard (“internal”) guidelines for other DFO/federal programs on Indigenous programming and using existing AFS/AAROM agreements to develop work plans and flow funding or develop customized agreements under the Terms and Conditions of the Integrated Aboriginal Contribution Management Framework | April 2020 | ||

| Update and finalize internal outreach strategy for AFS/AAROM and continue to implement | April 2020 | ||

| Finalize and release (in partnership with AAROM departments) standard information products and guidelines for other programs/departments that intend to partner/fund AAROM organizations (as part of the AAROM Marketing and Partnership Tool Kit) | April 2020 | ||

| Update all relevant guidance materials based on outcomes of AFS renewal and AFS-specific requirements | March 2022 | ||

| Recommendation 3 | |||

| Recommendation 3: Consistency of data It is recommended that the Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy, establish consistency in data collection, particularly with respect to performance data, the management of contribution agreements and recipient interactions, to ensure that data is being collected and managed centrally in a cohesive manner across the country. Rationale: As was found by this evaluation and the previous two, performance measurement data is not being collected by the programs; only anecdotal information is available to measure how the programs are achieving their expected results. In addition, information available in APGIS is inconsistent within and across regions, due in part to a lack of clear guidance related to the information that needs to be captured in APGIS and limited training having been received by users. |

|||

| Strategy | |||

| The Indigenous Programs Branch, within the Indigenous Affairs and Reconciliation Directorate, will take practical steps to improve and standardize, across all regions, data collection and management of performance and contribution agreement data through the development or updating of related guidelines, training, tools, business practices, and management/oversight functions. Due dates are for completion by all programs (AAAROM will likely rollout before AFS). | |||

| Management Action | Due Date (by end of month) | Status Update: Completed / On Target / Reason for Change in Due Date | Output |

| Establish Program information collection and management policies for staff, which clearly outline the program’s expectations with regards to contribution agreement, collection of performance data, and client relationship - data management. | April 2020 | ||

| Posting of APGIS application guidance materials on the intranet. | April 2020 | ||

| Conduct regular information management audits to ensure data is being collected and managed in accordance with the program policies. First audit to inform design of training (next item). | November 2020 | ||

| Develop and implement training based on the above policies for program staff regarding the administration of the programs, with a specific focus on consistent data collection, tracking of client interactions, and usage of the APGIS. Training should occur on a regular basis. | March 2021 | ||

| Reinforce the network of assistance available to staff with regards to the APGIS (e.g. the prominent listing of both APGIS Program and Regional Leads who are available to assist users with questions regarding the application). In particular, emphasize the role of the APGIS Leads with regard to suggesting changes and correcting errors within the application. | March 2021 | ||

[1] An eligible group composed of Indigenous communities that work together in relation to a watershed or ecosystem and meet certain requirements related to management practices.

[2] National Indigenous Fisheries Institute (2017). Program Review. Retrieved from http://indigenousfisheries.ca/en/indigenous-program-review-2-2/.

[3] An APGIS user is any DFO-CCG employee wishing to use APGIS for Transfer Payment Program administration, or to access information held within the application.

[4] AFS budgets and expenditures include funding allocated to the Fishery Guardian Program and the Aboriginal Funds for Species at Risk, but exclude the Allocation Transfer Program.

[5] By providing ongoing funding to support core operations, technical capacity and networks/relationships of AAROM organizations, the AAROM program is supporting a platform that can be used to deliver technical and engagement services tied to other DFO/federal/provincial programs as well as partnership with universities and industry.

[6] Word clouds are a visual representation of text data which show the importance of each tag by putting the focus on the most important components using font size.

[7] For example, “Centres and scientists in some regions are looking to increase opportunities to work with AAROM organizations in the collection and/or analysis of the data that will inform future CSAS science advisory processes”— 2018-19 DFO Evaluation, Evaluation of the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS), Report.

[8] DFO (2013-14). Evaluation of the Aboriginal Strategy and Governance Program. Retrieved from http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/ae-ve/evaluations/13-14/ASG_Final_Report-eng.html.

[9] DFO (2013-14). Evaluation of the Aboriginal Strategy and Governance Program. Retrieved from: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/ae-ve/evaluations/13-14/ASG_Final_Report-eng.html.

[10] DFO (2009-10). Evaluation of the Aboriginal Aquatic Resource and Oceans Management Program. Retrieved from: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/ae-ve/evaluations/09-10/6b103-eng.htm.

[11] These tools are also used by other Aboriginal Programs, but are presented here through an AFS/AAROM lens.

[12] From a sample of 23 out of 138 AFS recipients.

- Date modified: