Evaluation of the Salish Sea Initiative and the Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund

Final Report

March, 2024

Evaluation of the Salish Sea Initiative and the Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund

(PDF, 1.25 MB)

Table of contents

- 1.0 Evaluation context

- 2.0 SSI and AHRF Profiles

- 3.0 Evaluation findings

- 3.1 Summary of Key Findings

- 3.2 Relevance

- 3.3 Effectiveness

- 3.3.1 Efforts were made to meaningfully engage groups

- 3.3.2 SSI’s approach to engagement

- 3.3.3 AHRF’s approach to engagement

- 3.3.4 Co-development of SSI: Salish Sea Interactive Map

- 3.3.5 Co-development of SSI: Virtual workshop webinar series

- 3.3.6 Co-development of SSI: Arm’s-Length Fund

- 3.3.7 Co-development of AHRF

- 3.3.8 Participation and results: SSI

- 3.3.9 Participation and results: AHRF Phase 1

- 3.3.10 Participation and results: AHRF Phase 2

- 3.3.11 SSI and AHRF supported capacity building

- 3.4 Efficiency and delivery

- 4.0 Annexes

- Footnotes

1.0 Evaluation context

1.1 Overview

In accordance with the Departmental Evaluation Plan, an evaluation of two Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) accommodation measures, the Salish Sea Initiative (SSI) and the Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund (AHRF), was conducted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada's (DFO) Evaluation Division. The evaluation complies with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and meets the obligations of the Financial Administration Act.

1.2 Evaluation context, scope, and objectives

The evaluation covered the fiscal years 2019-20 to 2022-23 and was inclusive of DFO’s Pacific Region and Ontario and Prairie (O&P) Region. While the two accommodation measures were regionally led, the Programs Sector in National Headquarters provided support, reporting, and oversight of both. The evaluation was designed to provide evidence on where the accommodation measures were working well, as well as to identify where improvements could be made. It included an assessment of the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, and delivery of AHRF and SSI. As discussions regarding the Arm’s-Length Fund (ALF) for the SSI were still ongoing, the evaluation did not cover certain aspects such as governance structure and payment options which have yet to be finalized. DFO was also involved in the TMX Terrestrial Cumulative Effects Initiative (TCEI), however, it was led by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and is therefore not included in this evaluation.

1.3 Evaluation methodology and evaluation questions

The evaluation was designed to respond to the questions listed below. Information gathered from multiple lines of evidence was triangulated to address the evaluation questions.

The methodology included a document and file review, 39 interviews, financial and data analysis, and input was received from 11 Indigenous groups who participated voluntarily in the evaluation. See Annex A for the evaluation methodology, limitations, and mitigation strategies.

Evaluation Questions

Relevance

- To what extent do SSI and AHRF address the interests of Indigenous groups identified during TMX consultations?

- To what extent do SSI and AHRF align with the priorities of the federal government and the department?

Effectiveness

- To what extent were SSI and AHRF collaboratively developed and implemented with eligible Indigenous groups?

- To what extent are SSI and AHRF demonstrating results?

Delivery and Efficiency

- To what extent are SSI and AHRF delivered efficiently?

- What factors have facilitated or hindered the success of SSI and AHRF?

- To what extent have GBA+ considerations been integrated into SSI & AHRF?

2.0 SSI and AHRF Profiles

2.1 The TMX project and accommodation measures

The TMX project will twin the existing Trans Mountain pipeline, which transports crude oil and refined petroleum products from Edmonton, Alberta to refineries and terminals in British Columbia and Washington State. The TMX will also expand the Westridge Marine Terminal in Burnaby, B.C. The TMX was approved by the Government of Canada on June 18, 2019, and it is required to satisfy 156 conditions enforced by the Canada Energy Regulator.

In 2019, the Government of Canada re-initiated a Phase 3 consultation process with Indigenous groups along the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) project corridor. As a result, the Government developed eight accommodation measures to address the concerns of potentially impacted Indigenous groupsFootnote 1, including the SSI and AHRF.

The remaining six accommodation measures include:

- Co-Developing Community Response Initiative

- Enhanced Maritime Situational Awareness Initiative

- Maritime Safety Equipment and Training Initiative

- Quiet Vessel Initiative

- Terrestrial Cumulative Effects Initiative

- Terrestrial Studies Initiative

2.2 SSI profile

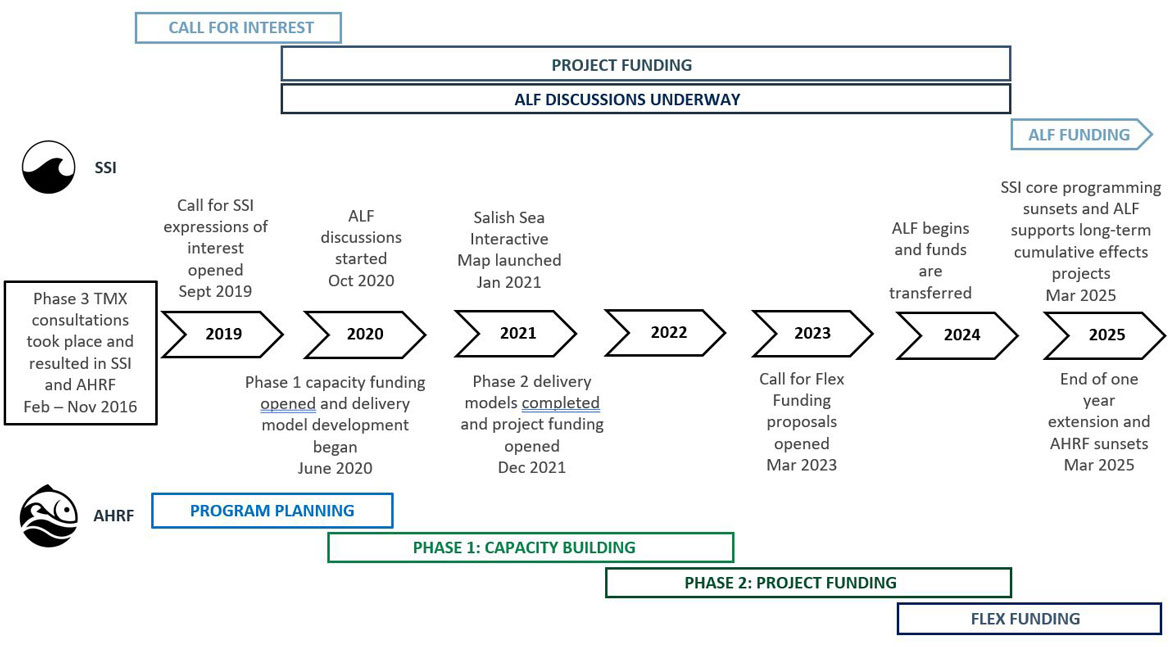

The SSI was developed to address concerns raised by Indigenous groups related to their capacity to understand and contribute to addressing cumulative effects in the Salish Sea. $114 million was budgeted from 2019 to 2025, including $91M in contribution funding. An additional $50 million in an Arm’s-Length Fund (ALF) will support longer-term cumulative effects projects, beyond 2025.

SSI provided funding to 33 eligible Indigenous groups to enable them to increase their technical and scientific capacity to conduct research, monitoring, and stewardship activities to identify valued ecosystem components (VECs) and monitor the cumulative effects of human activities on these ecosystem components over time, in the Salish Sea biozone.

2.3 AHRF profile

AHRF sought to address concerns raised by Indigenous groups about the potential impacts that TMX could have on fish and fish habitat, as well as the general state of fisheries resources based on cumulative effects from development projects. $85.9 million is available between 2019 and 2025, including the delivery of $75 million in contribution funding.

AHRF was designed to increase capacity within eligible Indigenous groups to protect and restore aquatic habitats that may be impacted by the TMX project or by the cumulative effects of development. Funding is available to 129 Indigenous groups whose communities or traditional territories are within the Fraser River Watershed and inland watersheds along the TMX pipeline and shipping corridor in the Salish Sea. Funded projects aim to support capacity-building activities (Phase 1) and Indigenous led aquatic habitat restoration activities (Phase 2).

See Annex B for more details about the SSI and AHRF, including a breakdown of the number of full-time equivalent (FTEs) and funding allocated for Vote 1 and Vote 10 expenses.

3.0 Evaluation findings

3.1 Summary of Key Findings

Overall, the evidence shows that SSI and AHRF are two successful accommodation measures co-developed with Indigenous groups.

Relevance

The evidence shows SSI and AHRF address the interests of Indigenous groups related to marine stewardship and aquatic habitat restoration in areas that are a priority to them. They allowed each recipient group to define what is important and where efforts and resources should be focused.

SSI and AHRF are well-aligned with current federal and departmental priorities to support fulfilling the Government of Canada’s commitments with respect to the TMX and to work in partnership with Indigenous Peoples.

Effectiveness

The evaluation found that SSI and AHRF were helpful in building the capacity necessary for Indigenous groups to collect baseline data and to identify priorities to address cumulative effects of development in marine and freshwater environments. Both SSI and AHRF collaboratively developed and implemented many engagement mechanisms and deliverables with eligible Indigenous groups, such as the Salish Sea Interactive Map and the AHRF Phase 2 delivery model.

At the departmental level, SSI exceeded its performance targets. The majority of eligible groups participated in SSI, with thirty-one out of thirty-three eligible First Nations participating.

AHRF provided capacity funding to the one hundred and nine eligible Indigenous groups with contribution agreements (CAs) in Phase 1 from 2020 to 2022. AHRF faced challenges with the disbursement of project funding in Phase 2 to the one hundred participating Indigenous groups. However, the extension of AHRF to March 2025 will provide additional time to ratify agreements, complete activities, and report on departmental outcomes.

Efficiency and Delivery

The SSI and AHRF were well-resourced and supported communities with funding processes. The application process was straightforward, and it was easy to apply for funding. Accommodation measures were flexible and broad, in terms of eligible activities. However, the delivery of an accommodation measure through a contribution program presented challenges and complexities, the majority of Indigenous groups who provided input into the evaluation are feeling frustrated and concerned about the sunsetting of the funds. Despite efforts to reduce administrative burden, reporting processes remained time-consuming for some Indigenous groups.

The evaluation found that the lack of or strained pre-existing relationships with some groups and/or the low capacity of some groups hindered the success of SSI and AHRF. Yet some external interviewees spoke to the positive impact that SSI and AHRF had on rebuilding relationships between involved Indigenous groups and DFO.

While the COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters limited engagement opportunities with Indigenous groups, the role of individuals within Indigenous communities, the amount of available funding, and the use of digital platforms were factors that enabled the success of SSI and AHRF.

With regards to GBA+ considerations, SSI and AHRF were exclusively dedicated to potentially impacted Indigenous groups consulted in the context of the TMX project. Both SSI and AHRF tried to address challenges such as community remoteness, limited internet connectivity, and low community capacity to support eligible Indigenous groups to engage meaningfully.

3.2 Relevance

3.2.1 Alignment with the priorities of the federal government and the department

SSI and AHRF are well-aligned with current federal and departmental priorities to support fulfilling the Government of Canada’s commitments with respect to the TMX and to work in partnership with Indigenous Peoples.

Alignment with the priorities of the federal government

SSI and AHRF support fulfilling the Government of Canada’s commitments with respect to TMX and responding to the Canada Energy Regulator’s findings by implementing two accommodation measures to address potential impacts on Indigenous rights and interests. The Government of Canada’s delivery of the accommodation measures is required as part of the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate, to uphold the honour of the Crown and to deliver on the commitments made both during Indigenous consultations on the TMX project and at the time of the Governor in Council’s approval of the project.

SSI and AHRF also strengthen Canada’s relationship with Indigenous Peoples. As indicated in the Speech from the Throne, Reconciliation is not a single act, nor does it have an end date. It is a lifelong journey of healing, respect and understanding. At the highest level, the accommodation measures support the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (see Box 1), and Canada’s reconciliation agenda.

Box 1 – UNDRIP

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is a comprehensive international human rights instrument on the rights of Indigenous Peoples around the world. Through 24 preambular provisions and 46 articles, it affirms and sets out a broad range of collective and individual rights that constitute the minimum standards to protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and to contribute to their survival, dignity and well-being.

In 2016, the Government of Canada endorsed the UNDRIP without qualification and committed to its full and effective implementation. The UNDRIP provides a roadmap to advance lasting reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

Alignment with DFO’s priorities

SSI and AHRF also align with the Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Canadian Coast Guard Reconciliation Strategy and DFO’s Pacific Regional Reconciliation Action Plan.

As indicated in the DFO Minister’s mandate letter, “We must move faster on the path of reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples.” SSI aligns with the mandate to create stronger partnerships with Indigenous and other coastal communities while strengthening marine research and science.

AHRF aligns with DFO's core responsibilities and commitments to reconciliation. The design of AHRF was based on two principles: the adoption of a collaborative design and delivery approach for program development; and support for capacity development so that Indigenous groups have the autonomy to reflect local interests and concerns. In addition, there is a significant effort being made towards involving all 129 eligible Indigenous groups in the work related to AHRF. There were multiple methods of engagement to ensure that every community had the opportunity to provide input on the final program elements (see section 3.3.7).

3.2.2 SSI and AHRF addressed the interests of Indigenous groups

SSI and AHRF addressed the interests of Indigenous groups related to marine stewardship and aquatic habitat restoration in areas of priority to them. The accommodation measures allowed each recipient group to define what was important and where to focus efforts and resources.

SSI and AHRF are a direct response to Phase 3 TMX consultations. As indicated previously, the accommodation measures supported Indigenous interests to increase capacity to conduct marine stewardship activities, to monitor and evaluate the impact of human activities on local marine systems, and to address watershed-level impacts on fish and fish habitat.

Indigenous groups’ habitat restoration and stewardship priorities

SSI and AHRF supported Indigenous groups to work on projects that prioritized areas of importance to each group, within the scope of the programs’ objectives. Interests in the areas of marine stewardship and aquatic habitat restoration varied from baseline data collection to spill prevention, community connection, and land and water (see section 3.3.7 for details on regional priorities). Indigenous groups were consulted about their goals and were supported to undertake projects and work related to the accommodation measures’ objectives. This approach supported prioritization of holistic thinking, traditional knowledge, and community-based decision-making, and enabled community members to contribute to the projects (e.g., Elders providing historical context for areas of importance to a community’s traditional ways of living).

AHRF program delivery was also co-developed to recognize these differences among groups and reflect Indigenous groups’ preferences for a sub-regional delivery model to support the interests most relevant to groups in each area.

Through these programs, Indigenous groups who contributed to the evaluation indicated that they have been able to demonstrate their capacity for on-the-water monitoring, community outreach, and education and they wish to continue their work in marine stewardship and habitat restoration into the future.

Gender-Based Analysis Plus

SSI and AHRF were exclusively dedicated to potentially impacted Indigenous groups consulted in the context of the TMX project. Both programs endeavored to address challenges such as community remoteness, limited internet connectivity, and low community capacity to support eligible Indigenous groups to engage meaningfully.

The programs also strived to incorporate cultural considerations. For instance, all meetings and engagement sessions began with an Elder-led prayer. As well, despite the challenge posed by the diverse range of languages present, both initiatives strived to create a welcoming and respectful space for participation, which included the incorporation of traditional languages.

Areas for improvement

Moving forward, Indigenous groups the evaluation team spoke with indicated they would like to see increased connections between departmental and federal programs as the efforts required by their groups for the coordination and cohesion of these multiple programs can be challenging. It was also difficult for a few Indigenous groups to consider the eight TMX accommodation measures separately, in addition to funding from other DFO CAs. A few Indigenous representatives who participated in the evaluation suggested combining the accommodation measures to help simplify the process, which would also align with a more holistic perspective. Finally, there was a certain level of apprehension from Indigenous groups the evaluation team spoke with about the long-term sustainability of SSI and AHRF endeavours, with the pipeline still under construction. A few Indigenous representatives the evaluation team spoke with said there was a discrepancy between the timelines of the measures and the anticipated lifespan of the TMX pipeline.

3.3 Effectiveness

3.3.1 Efforts were made to meaningfully engage groups

The SSI and AHRF measures were resourced to enable stronger engagement, including having dedicated teams to support Indigenous groups. Multi-pronged efforts were made by staff to meaningfully engage with Indigenous groups and these efforts were appreciated by most groups who participated in the evaluation.

For the purpose of this evaluation, meaningful engagement means a holistic understanding of the community, respect, and recognition and regard for the rights of Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 2.

For both SSI and AHRF, staff was put in place within DFO to better support meaningful engagement with Indigenous groups.

In each case, DFO teams dedicated to Indigenous engagement were established, and personnel were responsible for working with a subset of three to 18 groups with the aim of facilitating continuity of support and relationship-building throughout the duration of the projects.

Of those Indigenous groups who contributed to the evaluation, many shared positive feedback about the SSI and AHRF staff they worked with. Staff were said to be open to feedback from groups, transparent with their communication, flexible to changes in workplans, respectful in their interactions, and accessible through a variety of communication channels. Some internal staff and external interviewees also spoke to the impact SSI and AHRF personnel had on supporting steps toward rebuilding relationships between involved Indigenous groups and DFO.

"Concerns of Nations are being brought forward to AHRF and SSI teams, they [the teams] have been listening, and concerns are being acted on. That is meaningful."

SSI and AHRF teams took a distinctly different and multi-pronged approach to engagement.

A few groups who participated in the evaluation noted that the engagement approach for SSI and AHRF differed from other DFO programs. Some Indigenous groups the evaluation team spoke with felt staff were particularly well-suited for roles in engagement, and internal interviewees confirmed care was taken to hire the right fit for these positions. Both DFO teams made significant efforts to engage Indigenous groups throughout the accommodation measures and staff utilized a varied and adaptable approach to working with groups. Staff attempted to tailor methods of engagement to the preferences and capacities of individual groups, and they were effective in pivoting from in-person to virtual engagement, when necessary. These efforts to meaningfully engage throughout the measures were appreciated by most groups who contributed to the evaluation.

See sections 3.3.2 and 3.3.3 for an overview of tools and approaches to engagement used by DFO’s SSI and AHRF teams.

To engage SSI and AHRF recipient groups in the evaluation, members of the DFO evaluation team attended one SSI and one AHRF webinar workshop to introduce the purpose and planned process for the evaluation and to invite participation. Following these presentations, each engagement team offered suggestions on how best to follow up and gauge the interest of Indigenous groups. The evaluation team gathered perspectives from 11 Indigenous groups who volunteered to participate. See Annex A for more details.

3.3.2 SSI’s approach to engagement

"The individualized approach is what creates those experiences of meaningful engagement. Where there is a human connection or someone that is genuinely interested in the information you’re providing, it [engagement] is meaningful."

The SSI team emphasized open dialogue and worked with eligible groups to generate engagement approaches that worked for them.

At the outset, the SSI engagement team organized a multi-Nation webinar to inform eligible Indigenous groups about funds available. When the pandemic necessitated a pause to in-person engagement, the team implemented a virtual workshop series to continue information sharing and discussion. By March 31, 2023, a total of 17 multi-Nation workshops had been facilitated.

To ensure workshops were relevant and useful, an agenda planning committee, comprised of First Nation and Government of Canada representatives, was convened to select topics for discussion. Furthermore, each session began with an opening prayer, graphic recordings were used to document discussions, and many webinars were Indigenous-led.

Workshops covered several topics each session and offered opportunities for recipient groups to present progress on their projects, share strategies for overcoming challenges, consider useful tools and technology, discuss data collection and sharing, and review plans for the ALF. The number of Indigenous groups participating in the workshops fluctuated from July 2020 to July 2022. Of the nine workshops held within this time frame, six of the sessions had attendees from 17 or more eligible groups. During this time, there were several circumstances that prevented some groups from engaging in the SSI process. These circumstances are described later in the report in the efficiency and delivery section.

In addition to meeting regularly with all recipient groups, the SSI team also connected bi-laterally with individual groups by email, virtual meetings, and phone to support groups in developing projects, identifying unique funding needs, trouble shooting challenges, and modifying workplans, as needed.

The SSI team also circulated weekly emails regarding training and funding opportunities as well as scientific news and engaged with some groups through the co-development of the Salish Sea Interactive Map (SSIM) (See section 3.3.4 for details).

In January 2023, the SSI team hosted its first in-person workshop. Nearly 100 people attended, including those who attended virtually. The workshop provided the opportunity for eight Indigenous groups to share updates on their projects through plenary sessions or poster presentations. The workshop also offered groups the opportunity to meet the SSI team, DFO program representatives, and other key stakeholders in person, and to network, exchange ideas, and share information.

3.3.3 AHRF’s approach to engagement

"For their entire history, First Nations have shared information orally, yet the Government still expects written feedback. The working groups filled in the gap to allow Nations to contribute in their oral tradition. They offered space to sit together, have a discussion, share concerns and successes."

Similar to the SSI team, AHRF staff took an active, open, and tailored approach to engagement with Indigenous groups.

The AHRF engagement team worked with groups from the development to the implementation of project proposals, including working one-on-one to develop projects that aligned with funding requirements and adjusting project workplans as needs and interests evolved.

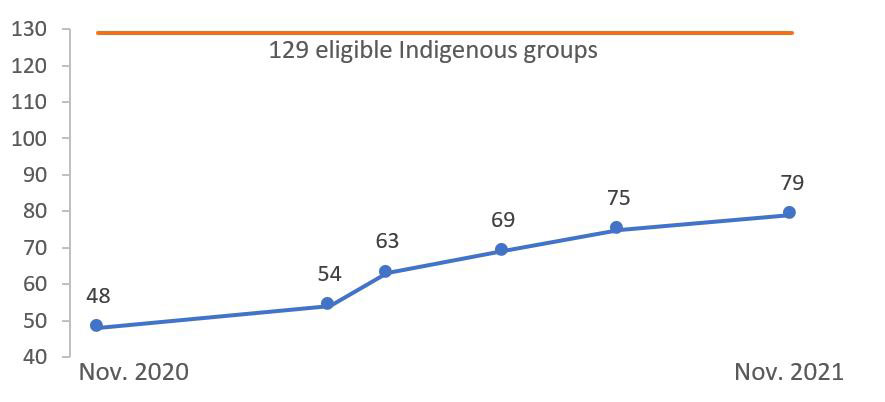

The team coordinated virtual working group meetings, which initially included all AHRF-eligible groups, however, over time, separate sessions were organized by region to tailor meeting content to regional contexts. Meetings were organized to maximize participation, including the use of polls to engage all attendees in discussions. The meetings were well-attended, and the number of Indigenous groups in attendance increased meeting over meeting from November 2020 to November 2021 (figure 1). Attendees appreciated the workshops as they offered a chance to connect with other groups, to present their projects, learn about useful tools for restoration work, and to identify opportunities for collaboration within their sub-regions.

Figure 1 - Text version

This figure depicts the number of AHRF-eligible Indigenous groups participating in virtual AHRF working group sessions between November 2020 and November 2021. It demonstrates an overall increase in participation over time, from 48 Indigenous groups in November 2020 to 79 Indigenous groups in November 2021.

| Date | Number of Indigenous groups participating in AHRF sessions | Number of eligible Indigenous groups |

|---|---|---|

| November 2020 | 48 | 129 |

| March 2021 | 54 | 129 |

| April 2021 | 63 | 129 |

| June 2021 | 69 | 129 |

| August 2021 | 75 | 129 |

| November 2021 | 79 | 129 |

The AHRF team also engaged with interested sub-regions to establish a technical review committee to review all Phase 2 proposals prior to DFO assessment. Further details on this review process are in section 3.3.7.

AHRF staff also made use of:

- Online surveys between meetings,

- One-on-one virtual discussions,

- A dedicated email inbox

- Telephone calls

When possible, the AHRF team conducted site visits. Representatives from Indigenous groups the evaluation team spoke with valued the opportunity to offer tours of their sites and to share on-the-ground work. Indigenous groups and AHRF staff interviewed felt this in-person engagement fostered deeper connections and strengthened relationships.

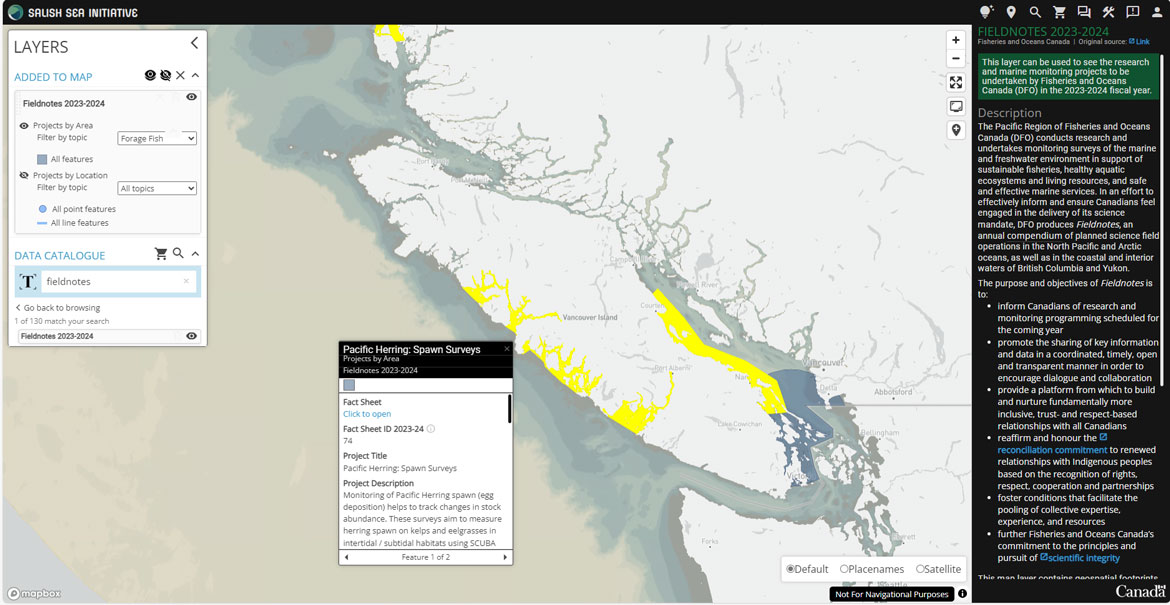

3.3.4 Co-development of SSI: Salish Sea Interactive Map

SSI co-developed many engagement mechanisms and deliverables, such as the Salish Sea Interactive Map (SSIM), which created opportunities for Indigenous groups to network and share different approaches for marine stewardship.

The SSI Science Team along with many marine Indigenous groups collaboratively and successfully created a key deliverable, the SSIM, a geographic information system (GIS) product, which is funded by DFO under TMX accommodation funds until March 2025.

The SSIM creates, manages, analyzes, and maps all types of data. There were 33 Indigenous groups invited to participate in the Salish Sea Initiative, and 27 of these groups attended at least one co-development SSIM session. Three additional First Nation aggregates also attended.

The primary objectives of the SSIM are to empower Indigenous groups by supporting the sharing of existing data and information on VECs (e.g., the southern resident killer whale, salmon, shellfish, and traditional land use), and building geospatial capacities within these groups. The SSIM also includes resources and tools to support marine cumulative effects work. The SSIM is intended to be modified over time as ideas and needs develop. By July 2023, the SSIM was up to 182 data layers.

Gender Based Analysis Plus

The interactive map was purposefully designed to include Indigenous language keyboards for all groups along with functionalities to include video, audio, pictures and written stories. Indigenous groups also controlled traditional place naming.

Additionally, participating Indigenous groups contributed cultural and biological data to the map and various members of groups, including Chief, Council, and Band members had access to view and explore the many layers of data. As such, the interactive map is one of the ways that SSI has contributed to capacity building within Indigenous groups.

A few Indigenous groups who provided input into the evaluation highlighted that the co-development of the map with the SSI team was a productive and enjoyable experience and there was great enthusiasm from those participating. The SSIM was a marker of success and an indication that SSI was on the right path with Nations regarding meaningful engagement. The SSIM was also an area where some Indigenous groups may have chosen to share Indigenous Knowledge.

3.3.5 Co-development of SSI: Virtual workshop webinar series

Over the course of the SSI program, various engagement mechanisms were co-created, such as SSI committees, webinars, surveys, and science sessions.

Another mechanism that was implemented successfully included the co-developed workshop webinar series. Recipients of SSI had the opportunity to participate in monthly workshops that were facilitated by DFO and included rotating community leadership. The workshops acted as an opportunity for recipients to network with DFO’s science and engagement teams, regulators, and other Indigenous groups. Through the meetings, recipients learned about different approaches to marine stewardship and useful tools and equipment for the work. The meetings also provided opportunities for interested groups to present their own ideas and share information and preliminary learnings coming out of data collected. The meetings were organized to foster information exchange and two-way dialogue.

The DFO science team provided support by assisting in the development of visions, goals, and science-focused Salish Sea stewardship activities. This included sharing new and pre-existing data on environmental components to help with comparisons between current and future conditions and identifying relevant training opportunities and collaborations with other TMX initiatives, government, and non-government organizations, when applicable. They also created a toolkit of resources to support science-focused stewardship activities, with tools such as fact sheets, guidance documents, standard operating procedures, and equipment requirements for sampling and monitoring.

3.3.6 Co-development of SSI: Arm’s-Length Fund

DFO and eligible Indigenous groups are co-creating an Arm’s-Length Fund (ALF) through an initial investment of $50 million.

The ALF was proposed during the National Energy Board’s Reconsideration process that took place in 2018-2019. The vision put forward was to establish an Indigenous-led Investment fund to generate own-source revenue to support longer-term marine stewardship activities beyond March 2024. The approach emphasized Indigenous groups’ leadership in co-developing and managing the fund and the projects that it will eventually support. The purpose of the fund is to support long-term Indigenous groups' participation in marine spatial planning and to support ongoing marine stewardship activities that are priorities for Indigenous groups.

The ALF is currently open to all 33 eligible First Nations. Co-development discussions began in 2020, and from the summer of 2020 to the winter of 2021, there were six ALF webinars held as well as the ALF planning committee meetings. In January 2022, a Working Group consisting of eight nominated representatives from First Nations was established to work alongside DFO representatives. This was followed by a series of weekly meetings that were complemented by a few crosswalk sessions. An intensive two-day in-person session was held in January 2023, where a deep dive was taken into the documentation required to implement the approach. A non-profit Society was then established to receive funds on behalf of Nations.

A Nation-to-Nation Agreement outlines the governance structure for the Society and parameters for accessing funds. DFO acts as a secretariat to support, with no formal role in administering funds.

There is no specific timeframe given for the ALF when it comes to the distribution of funds. The state of intent is to support long-term participation in stewardship monitoring activities after the core SSI program sunsets. Indigenous groups mentioned that the co-development of the ALF faced some limitations as a strategy was already in place from the beginning, leaving limited options. The discussions regarding funding transfer options also caused significant frustration among groups. Reaching a consensus has proven challenging due to concerns regarding the availability, timing, and management of the funding. Nevertheless, the SSI has made progress on the ALF, and is advancing a proposed approach that has been designed to reflect the varying interests of Nations.

During the data collection period for the evaluation, discussions regarding the ALF were still ongoing. As such, the evaluation did not cover certain aspects of the ALF, such as the governance structure and payment options, as these have yet to be finalized.

3.3.7 Co-development of AHRF

AHRF’s Phase 2 delivery model was collaboratively developed with Indigenous groups from the outset. The collaborative approach responded to the groups’ engagement needs and aquatic restoration priorities and supported Indigenous groups in determining the way AHRF would be delivered in Phase 2. This process resulted in tailored funding mechanisms and project proposal assessment processes in each region.

Collaborative development

One of AHRF’s primary goals was the collaborative development of AHRF priorities and activities with Indigenous groups for Phase 2 project delivery. It was important to have Indigenous groups involved in the decision-making process to ensure meaningful input for the projects they wanted to carry out under the second phase. Instead of presenting Indigenous groups with a predetermined model, AHRF collaboratively developed the Phase 2 delivery models and project proposal assessment processes which allowed Indigenous groups to have a say in how proposals would be reviewed.

"…a good example of a step in the right direction. A step forward in terms of co-development: coming with [the] ingredients, not the cake."

AHRF’s collaborative approach engaged with Indigenous communities from the start of the program to understand sub-regional priorities. For instance, the restoration of salmon habitat and the salmon population were important priorities in the Fraser region, whereas training and monitoring were emphasized in Alberta. The co-development approach also allowed for a good understanding of the individual communities’ engagement needs. This was achieved by asking the Indigenous groups about their preferences for organizing themselves in Phase 2, such as whether they wanted one large region or smaller sub-regions. The process also involved discussing the type and timings of engagement with DFO, and any limitations to groups’ participation in AHRF-related meetings (e.g., limited staffing, other projects). The co-development was carried out through regional working groups, regional engagement sessions (which included four surveys and several in-session polls and discussions), and direct meetings with Indigenous groups.

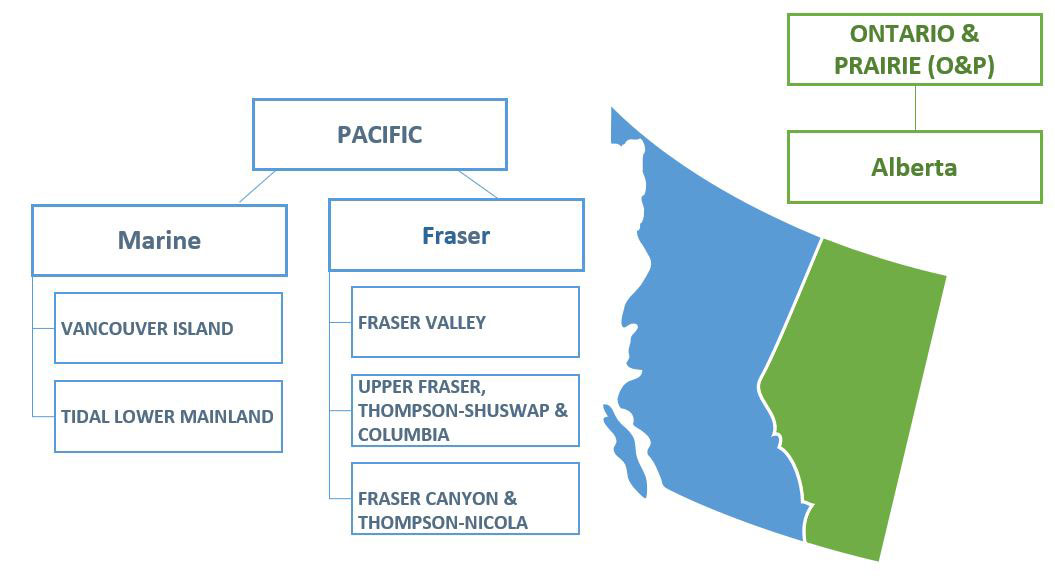

AHRF delivery model

As part of the collaborative process, DFO was able to offer Indigenous groups varied options within the scope of AHRF objectives for the Phase 2 delivery model. However, it ultimately looked to Indigenous groups to propose the final model through a voting process that resulted in the establishment of a number of sub-regional delivery models (Figure 2), based in part on geography, geology, and population demographics. As one of the major outcomes of the collaborative process during Phase 2, the sub-regional delivery model is an example of recognizing the value of working with Indigenous groups from the outset. The five sub-regions in the Pacific region were the following: Upper Fraser, Thompson-Shuswap & Columbia, Fraser Canyon & Thompson-Nicola, Tidal Lower Mainland, and Vancouver Island. In the O&P region, all recipients in Alberta are under one delivery model. The sub-regionalization allowed Indigenous groups to focus on the aquatic restoration issues that were most important to them, which may vary based on different geographic areas.

Figure 2 - Text version

This figure depicts the sub-regional breakdown of the Pacific and O&P regions that were co-developed during AHRF Phase 2. The Pacific region is divided into the Marine and Fraser sub-regions. These sub-regions are then further divided: the Marine sub-region includes Vancouver Island and the Tidal Lower Mainland; the Fraser sub-region includes the Fraser Valley, the Upper Fraser, Thompson-Shuswap & Columbia, and the Fraser Canyon & Thompson-Nicola areas. The O&P region only includes Alberta.

The collaborative process also gave groups the opportunity to decide on which funding mechanism was best suited to their sub-regional priorities (e.g., the decision to pool funds – see box 2) and determine the process through which their project proposals would be reviewed. All Phase 2 project proposals had the following components: project objectives and description, work plan, and budget. Ensuing steps in the proposal submission process were then determined by each sub-region. For example, the Fraser Valley and the Upper Fraser, Thompson-Shuswap & Columbia sub-regions chose to include a project proposal assessment by a Technical Review Committee, prior to it being assessed by DFO. The committee was intended to provide subject matter expertise on restoration project proposals to ensure that project development maximized benefits to fish and fish habitat.

Box 2 – AHRF Phase 2 Funding Options

For Phase 2 of AHRF, all eligible recipients had access to a "Base" funding allocation of $250,000 or $500,000 for Indigenous-led restoration projects. The exact amount was determined by the respective communities. In one region, some funds were used to create a ‘pooled’ funding allocation to support larger projects. Not all eligible groups in that region participated in pooled funding. Following Phase 2, the program then opened for ‘Flex’ funding proposals, whereby groups could apply for any remaining AHRF funds, and every community was eligible to receive minimum funding for their top priority project or activity. AHRF had received 75 expressions of interest for flex funding by June 2023.

3.3.8 Participation and results: SSI

At the departmental level, SSI is meeting its performance targets. The majority of eligible groups participated in SSI, with 31 out of 33 eligible First Nations participating. SSI continues to be on track to ensure delivery is on time and on budget by the March 2025 end date.

Thirty-one Indigenous groups in the Salish Sea have the capacity to participate in the SSI, collect and share data on cumulative effects and marine planning, and continue to participate in initiatives on cumulative effects in the Salish Sea. As such, SSI is on track to meet departmental results (as shown in table 2) by its March 2025 end date.

| SSI Program Results | Status (by June 2023) |

|---|---|

| Indigenous Groups participate in work on cumulative effects in the Salish Sea | On track |

| Indigenous groups in the Salish Sea area have science, technical and engagement capacity to participate in the implementation of the Salish Sea Initiative | On track |

| Indigenous groups in the Salish Sea area have the capacity to collect and share data on cumulative effects and marine planning within the Salish Sea (new performance indicator following 1-year extension) | On track |

| Indigenous Groups continue to participate in initiatives on cumulative effects in the Salish Sea (new performance indicator following 1-year extension) | On track |

Table 2 notesSource: DFO Performance Information Profiles |

|

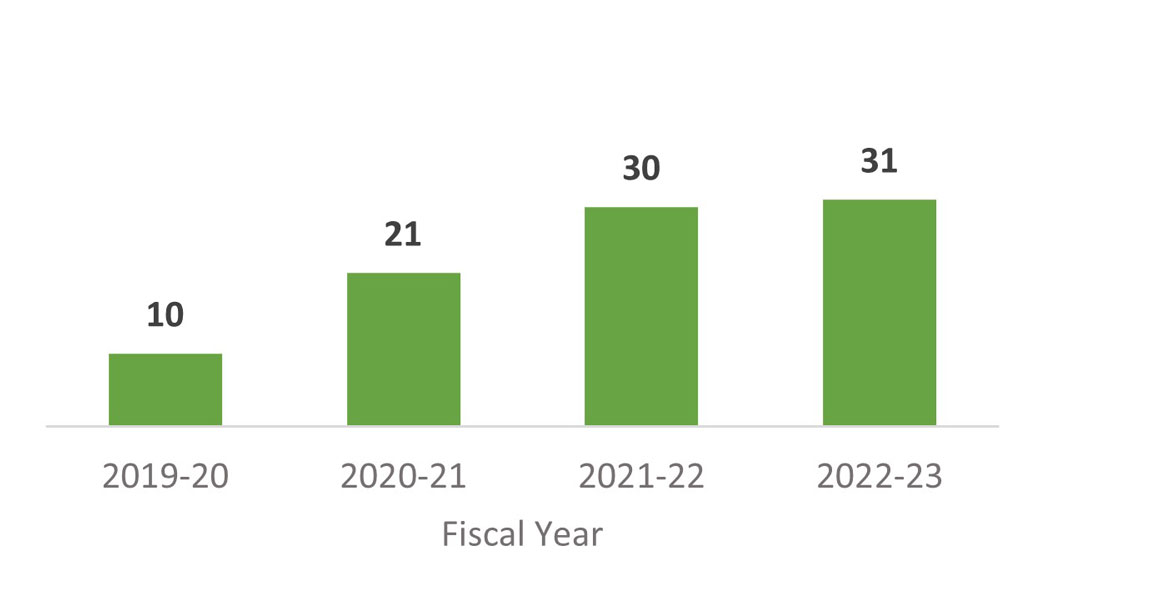

In its first year (2019-20), 10 out of the 33 eligible First Nations signed SSI CAs with all agreements focused on capacity building (figure 4). Although only representing a third of eligible First Nations, DFO experienced tight deadlines and staffing shortfalls this first year. In 2020-21 and 2021-22, there was an increase in the number of First Nations signing SSI CAs (21 out of 33 and 30 out of 33 respectively). By its fourth year (2022-23), 31 eligible First Nations had signed SSI CAs (i.e., over 90 %) and were participating in work on cumulative effects in the Salish Sea.

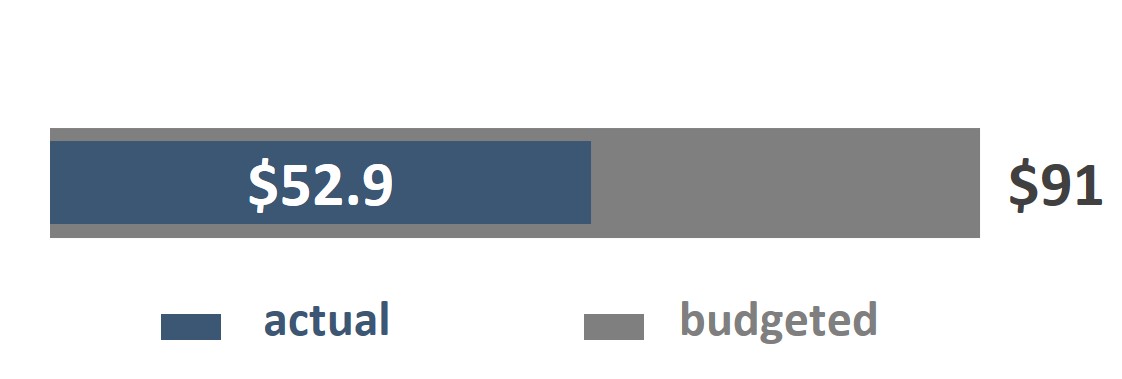

Eligible SSI participants are also actively engaged and participating in the accommodation measure through regular participation in SSI Webinars, co-development of the SSIM, and SSI ALF meetings. By June 2023, approximately $52.9M (58 %) of the total $91M SSI grants and contributions (G&C) funding envelope had been disbursed (figure 3), and $73M (or 80%) had been committed at that time. As SSI was 75% through the duration of its program delivery, it is considered on track.

Figure 3 - Text version

This figure depicts the amount of SSI contribution funding that was disbursed by June 2023, totaling $52.9M, in comparison to the overall budget, totaling $91M.

Figure 4 - Text version

This figure depicts the number of SSI-eligible Indigenous communities that participated in each fiscal year between 2019 and 2023. In fiscal year 2019-2020, there were 10 communities. In fiscal year 2020-2021, there were 21 communities. In fiscal year 2021-2022, there were 30 communities. And in fiscal year 2022-2023, there were 31 communities participating.

3.3.9 Participation and results: AHRF Phase 1

AHRF was successful in providing capacity funding to 109 eligible Indigenous groups with contribution agreements in Phase 1 from 2020 to 2022, which has been disbursed.

For AHRF, a key focus for program objectives in Phase 1 (capacity funding) was ensuring eligible Indigenous groups had the capacity to participate in its collaborative development and inform Phase 2 (project delivery) of the accommodation measure (table 3).

| AHRF Program Results | Status (by June 2023) |

|---|---|

| Partnerships with Indigenous groups are established | Completed |

| Indigenous groups have increased capacity to support the restoration of valued marine and freshwater aquatic habitat | Completed |

Table 3 notesSource: DFO Performance Information Profiles |

|

The proposals submitted starting in June 2020 under Phase 1 of AHRF had a range of capacity-building activities and were submitted by eligible groups with varying levels of baseline capacity. All eligible groups were engaged multiple times to discuss participation in the accommodation measure. However, some groups chose not to participate due to political concerns, lack of interest, or capacity challenges.

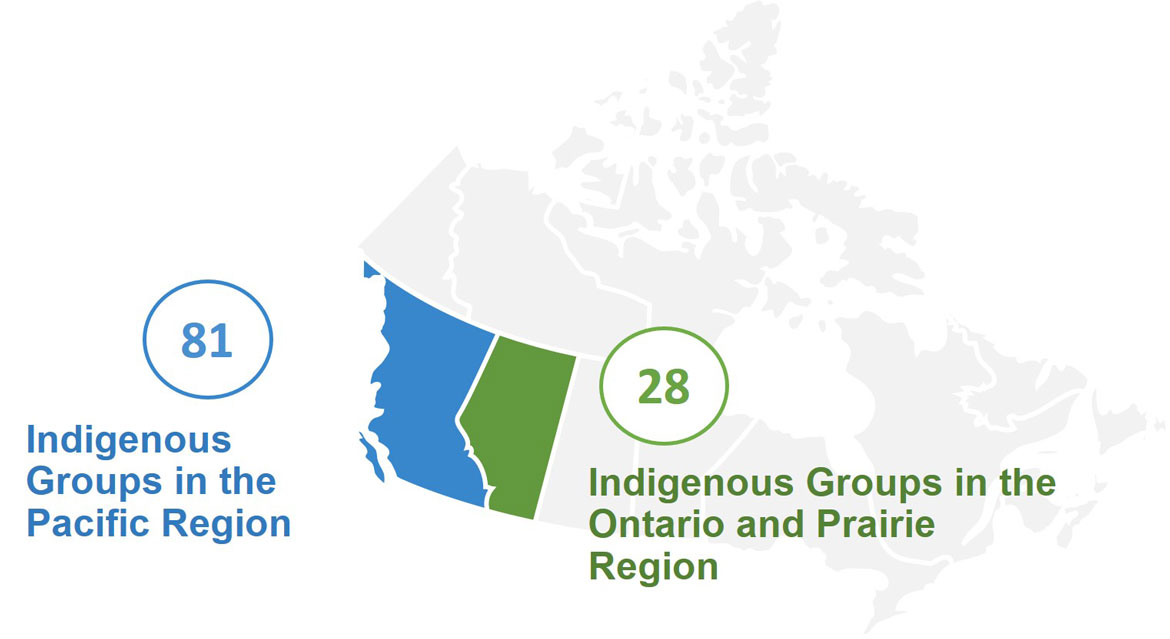

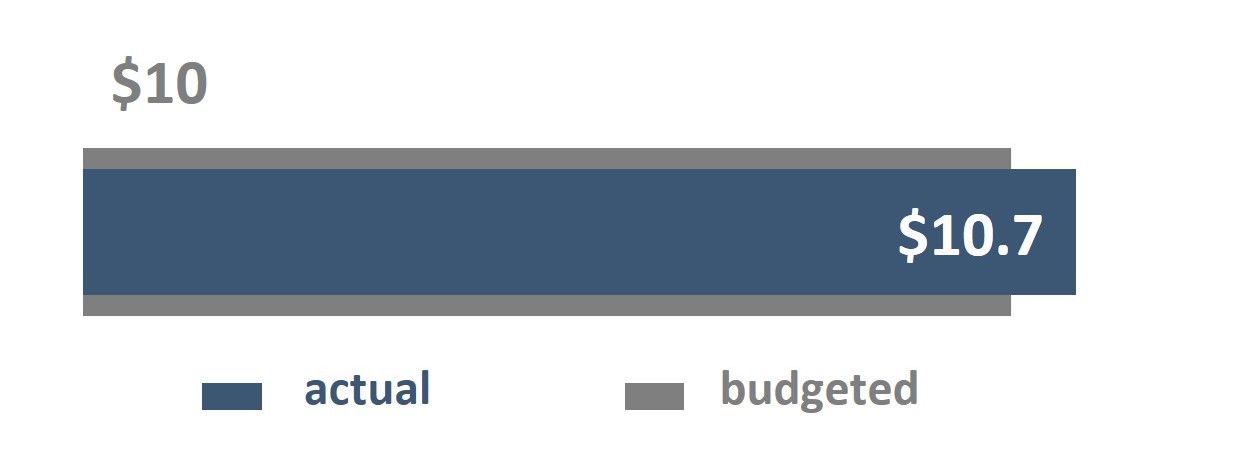

By the conclusion of Phase 1 in December 2022, 109 out of the 129 eligible Indigenous groups (figure 5) had entered into an AHRF contribution agreement. These agreements represented a commitment of $10.7M, which has all been disbursed (figure 6).

Figure 5 - Text version

This figure depicts the number of AHRF-eligible Indigenous groups participating in Phase 1, based on region. There were 81 Indigenous groups in the Pacific region, and 28 in the O&P region.

Figure 6 - Text version

This figure depicts the amount of AHRF Phase 1 contribution funding that was disbursed by June 2023, totaling $10.7M, in comparison to the overall budget, totaling $10M.

3.3.10 Participation and results: AHRF Phase 2

AHRF faced challenges with the disbursement of project funding in Phase 2 to the 100 participating Indigenous groups. However, the extension of AHRF to March 2025 will provide additional time to ratify agreements, complete activities, and report on departmental outcomes.

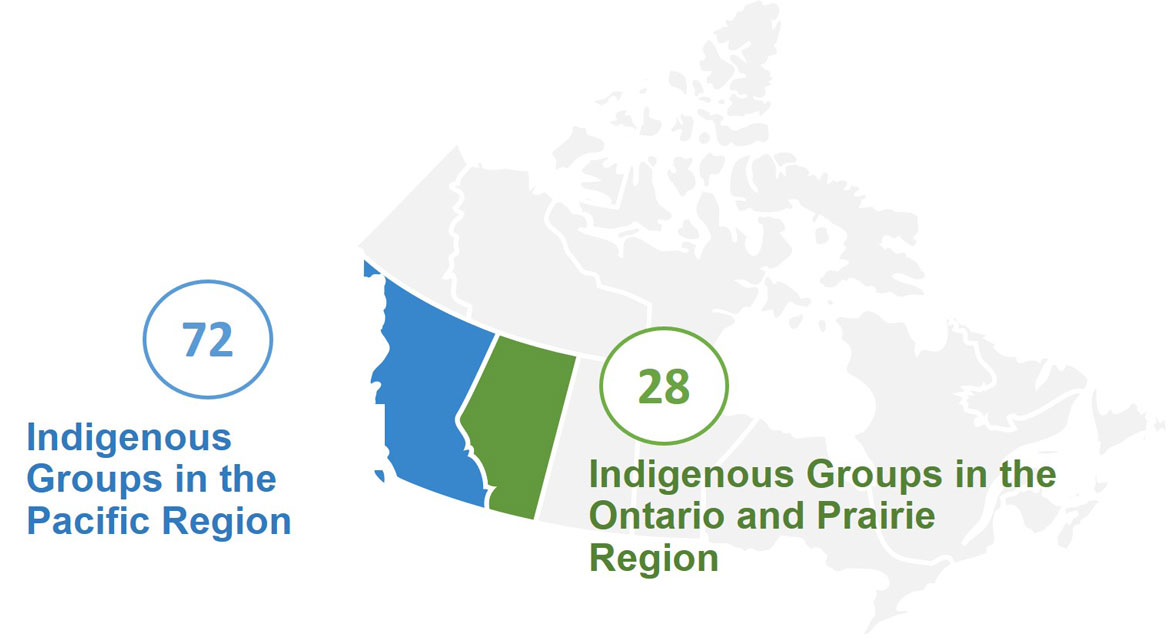

The Phase 2 (project funding) delivery model that were collaboratively developed in Phase 1 with eligible Indigenous groups were finalized and implemented in December 2021 when Phase 2 was open for proposal submissions. As of June 2023, 100 eligible groups were participating in Phase 2 of AHRF (figure 7).

Figure 7 - Text version

This figure depicts the number of AHRF-eligible Indigenous groups participating in Phase 2, based on region. There were 72 Indigenous groups in the Pacific region, and 28 in the O&P region.

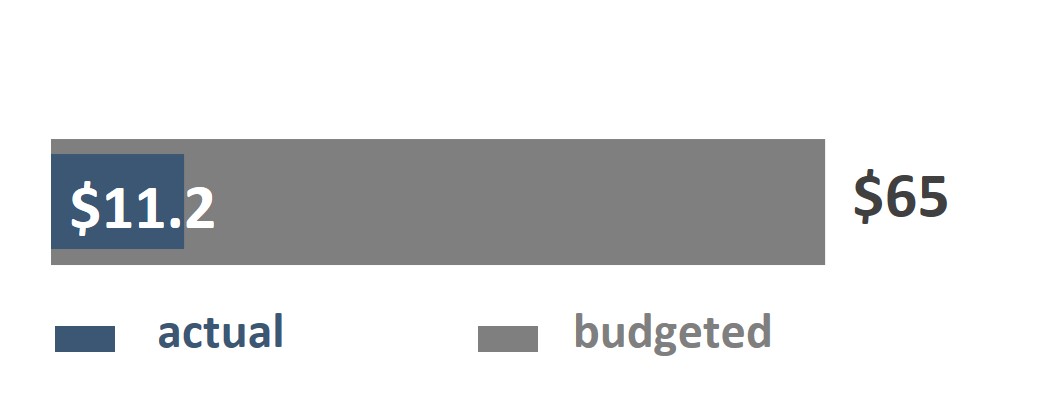

By June 2023, $11.2M out of a total of $65M budgeted funding was disbursed (figure 8). Delays in disbursement are in part due to an insufficient number of staff processing a large number of proposals. However, AHRF continued to backfill positions, secure short-term support, and increase capacity to process proposals and disperse funding.

Figure 8 - Text version

This figure depicts the amount of AHRF Phase 2 contribution funding that was disbursed by June 2023, totaling $11.2M, in comparison to the overall budget, totaling $65M.

The decrease in participation from Phase 1 was due to a few reasons. As Phase 1’s expenditure timeline was extended as a result of factors such as COVID-19 and the BC floods and wildfires, many communities continued to focus their efforts on the completion of Phase 1 activities, before turning their attention to Phase 2 applications. Moreover, these unexpected events also impacted some groups’ ability to meaningfully participate in the accommodation measure for Phase 2.

The extension of AHRF to March 2025 will significantly contribute to helping AHRF meet performance objectives (Table 4), including some new indicators and targets that were added following the 1-year extension. Many workplans are actively being negotiated with eligible Indigenous groups. The program expects to meet targets and will contribute to departmental outcomes on Indigenous participation in initiatives on habitat restoration.

| AHRF Program Results | Status (by June 2023) |

|---|---|

| Indigenous groups participate in initiatives on habitat restoration, which contributes to addressing adverse impacts to fish and fish habitat | Delayed |

Table 4 notesSource: DFO Performance Information Profiles |

|

Looking forward: According to program data, AHRF has now received enough proposals to fully expend its $65M G&C envelope for Phase 2. By September 2023, AHRF had committed $48.4M to Phase 2 proposals, with a remaining $15.8M available for Flex Funding proposals.

3.3.11 SSI and AHRF supported capacity building

SSI and AHRF supported capacity building for Indigenous groups. Capacity built varied by group and SSI and AHRF supported groups to determine which activities to use to restore aquatic habitats and enhance marine stewardship within their territories. Through the measures, Indigenous groups invested in three key areas, including: human resources, training, and equipment and capital assets.

Representatives from Indigenous groups who participated in the evaluation indicated that SSI and AHRF supported them to build the capacity necessary to restore aquatic habitats, to collect, analyze, and share data related to the cumulative effects of human activities, and undertake marine stewardship activities within their traditional territories. The wide scope of the accommodation measures enabled each group to determine their unique capacity needs and where investments would be made. More broadly, through SSI and AHRF funding, Indigenous groups invested in three key areas; human resources, training, and equipment and capital assets.

Human Resources

Investments in human resources allowed groups to build administrative capacity. Groups hired consultants and staff, including biologists, habitat restoration coordinators, and marine stewardship managers, who at times built entire programs from the ground up. These personnel hired additional staff, such as conservation or GIS specialists and marine technicians, organized staff training, developed restoration and stewardship plans, and managed all aspects of funded projects, including reporting.

Training

Through SSI and AHRF, groups also increased their technical and scientific capacity, through a myriad of training, from boat safety and drone operation, to ecological restoration and on-the-ground field work, such as water sampling and acoustic monitoring. This led to the establishment of skilled restoration and stewardship professionals, community champions, and the formation of groups like land caretakers and waterkeepers, in some communities.

Equipment and Capital Assets

SSI and AHRF funding allowed groups to purchase equipment necessary to conduct habitat restoration and marine stewardship work, and to collect baseline data, such as underwater remote-operated vehicles (ROVs) to monitor the sea floor, water quality monitoring buoys to assess pH and contaminant levels, and aerial drones to conduct shoreline surveys (see images below for examples of equipment). Groups were also able to invest in capital assets, such as vessels and trucks.

Investments made allowed groups to build capacity necessary to carry out habitat restoration and stewardship activities that were meaningful to them and that had potential for positive impact on local ecosystems and communities. Groups also built the capacity to participate in decision- making, exchange knowledge, protect culture, provide outreach and education, and sustain the work into the future.

Meaningful and impactful action

Investments into key areas allowed groups to build capacity to conduct activities that were meaningful to them, and which had the potential for positive impact, such as collecting baseline data, identifying priorities to address cumulative effects of development and climate change in marine and freshwater environments, managing invasive species and erosion to restore traditional clam beds or fish spawning pools, or shoreline and seabed mapping to protect culturally important and ecologically sensitive marine ecosystems.

Participation in decision-making

SSI and AHRF helped a few groups to better position themselves to participate in key decision-making. Most groups who participated in the evaluation shared that they relied heavily on input from the community to ensure decisions made reflected their priorities, and they noted being enabled to move from participants in discussions, to collaborating as full partners with governments and other groups.

Knowledge transfer and exchange

Knowledge transfer and exchange within and outside of the community was also facilitated through SSI and AHRF funding. Indigenous Knowledge was shared by Elders and other Traditional Knowledge Keepers with project personnel, which in turn informed workplans and activities. At times, Traditional Knowledge was also layered with western science to maximize results.

Cultural capacity

SSI and AHRF played a role in supporting groups to protect cultural capacity, through supporting the restoration of traditional harvesting sites and food gathering practices, protecting historically and culturally significant spaces, and enabling the return of traditional skills in conservation and stewardship to the People.

Community outreach and education

Capacity for community outreach and education was enhanced through SSI and AHRF. Half of the groups the evaluation team spoke with indicated they used funding to support youth engagement and community events to educate and build interest and investment in habitat restoration and marine stewardship work.

Capacity for future work

Relationships built with other groups, governments, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) will support future collaborative efforts, while the hiring and training of community members for careers in habitat restoration and marine stewardship, coupled with investments in equipment and other assets, will support ongoing restoration and stewardship efforts.

3.4 Efficiency and delivery

3.4.1 SSI and AHRF are delivered efficiently

The SSI and AHRF accommodation measures were well-resourced from the outset. Groups were provided with support to navigate funding processes, including proposals and contribution agreements. This resulted in a more efficient review and approval of projects.

Program delivery

To provide the accommodation measures, the government of Canada created SSI and AHRF as contribution programs, which have specific application and reporting requirements. However, the application process for both SSI and AHRF (Phase 1) was straightforward, making it easy for eligible groups to apply. Indigenous groups who provided input to this evaluation found the SSI and AHRF funding application process straightforward and that it was easy to apply for funding.

The SSI application process was less formal compared to other G&C programs. There was no formal contribution application process. Once a First Nation expressed their interest in SSI and submitted an initial expression of interest for funding, the SSI team collaborated with the Nations to identify eligible program activities and associated budgets in a work plan. The work plan then formed the basis of a contribution funding agreement. At the start of each fiscal year, an equal notional allocation per Nation was identified to guide work plan development.

During the capacity-building phase, the AHRF team worked collaboratively with groups to determine how to allocate funding and a collective decision was made to offer a maximum amount of $100K per community for capacity building. Interested groups applied for funding, and once approved, worked with the AHRF team to finalize workplans to inform contribution agreements.

Support from staff

SSI consisted of a core team, which comprised an engagement team, a G&C team, in addition to a Science team. It had a total of 13 FTEsFootnote 3 to support 33 eligible groups.

AHRF was jointly delivered in Pacific and O&P regions to 129 eligible Indigenous groups. For the first three years, staffing levels were 12 FTEs and this number rose to 13 FTEs for the final three years of the accommodation measure. These core staff supported programming and negotiations and drew on additional resources shared with TCEI (up to 5 FTEs) to support G&C delivery for both regions.

The community engagement teams assisted in supporting communities with lower capacity with support in developing their proposals, and various options were explored to minimize administrative burdens. The engagement coordinators played a crucial role in facilitating effective communication between DFO and the Nations by translating government terminology and explaining processes.

Funding

SSI and AHRF’s available funding totaled $166 million from 2020-2025, with an additional $50 million for a co-developed Arm’s-Length Fund beyond the 5-year mark for SSI. The accommodation measures were not application-based, which meant that 129 groups for AHRF and 33 Indigenous groups for SSI were eligible for the funding. Many groups reported that the funding available was unprecedented and it enabled them to carry out projects that would be otherwise too expensive.

Approval of CAs rested with the Regional Director in DFO Pacific and O&P Regions, rather than the National Headquarters. The development of CAs was efficient and funds were approved quickly. Once approved, the disbursement of funds through CAs was quick and efficient, and there have been no issues reported for SSI and for AHRF Phase 1. However, as previously noted, there have been some difficulties in the disbursement of funds for AHRF Phase 2 (see section 3.3.10).

3.4.2 Flexibility played a key role in the delivery of SSI and AHRF

The accommodation measures were flexible in terms of financial adjustments and in responding to unexpected events and delays. They were also broad in terms of eligible activities, allowing for the evolution of community priorities.

SSI and AHRF flexible approaches

During the interviews, flexibility emerged as a common theme when describing what is working well in SSI and AHRF. DFO's experience has shown that a flexible and adaptive approach is key for collaborative program development with Indigenous groupsFootnote 4. SSI and AHRF took this approach and were widely appreciated for their flexibility in their work with Indigenous groups, prioritizing understanding their needs and circumstances, which made them stand out from other programs.

There is evidence that SSI and AHRF employed flexibility at the program levels. For instance, SSI staff were flexible to make changes to CAs to suit the needs of the groups. This included options for a single-year or multi-year agreements, as well as amending existing agreements. SSI also welcomed feedback from participants on areas that could be improved, such as youth development and suggestions on webinars.

Eligible activities

In the same way, Indigenous groups who participated in the evaluation mentioned that AHRF was flexible and adaptable to community interests and needs as well as the project’s evolution. The eligibility criteria for projects are quite flexible. For instance, Indigenous groups the evaluation team spoke with expressed that AHRF allows for a broad scope of eligible activities that are relevant to habitat protection, recovery, and stewardship, both on land and in the sea. Some groups who contributed to the evaluation also mentioned that AHRF's design enables innovative approaches to habitat restoration.

Terms and conditions

Since 2022, both SSI and AHRF have been operating under DFO’s Aquatic Species and Aquatic Habitat Integrated Terms and Conditions, which are dedicated to Transfer Payment Programs. Previously, they had separate terms and conditions. This change allowed SSI and AHRF to identify areas that needed improvement and to achieve more consistency in agreements. Overall, the new terms and conditions have been working well for SSI and AHRF.

SSI and AHRF leveraged Appendix K of the Treasury Board of Canada’s Directive on Transfer Payments to provide flexibility in how the funds were delivered. This flexibility allowed Indigenous groups to carry forward funds, which was greatly appreciated, especially at times when there were issues with supply and demand. The ability to carry forward funds and not be restricted to spending them in a single fiscal year was also noted as a positive aspect of the delivery of the accommodation measures.

Extension to respond to external factors

The flexibility of the accommodation measures to respond to external factors, including COVID-19 and wildfires was also highlighted. Delays resulted in the extension of AHRF Phase 1 to December 31, 2022, and the overall program delivery of SSI and AHRF was extended by one year, through 2024-25, which was also seen as helpful.

3.4.3 Challenges

The delivery of an accommodation measure through a contribution program presented challenges and complexities. The sunsetting of the funds created frustration and concern amongst groups about job security and uncertainty around the sustainability of their projects. Despite changes being made to reduce the administrative burden on Indigenous groups, some still found reporting processes to be onerous and time-consuming.

Program design

The delivery of an accommodation measure through the chosen funding mechanism (i.e., a contribution program) presented some challenges and complexities and there seemed to be miscommunication with Indigenous groups regarding the delivery of funds. Therefore, additional work was needed to explain why SSI and AHRF were contribution programs.

During the evaluation, many suggestions were made regarding the design of the accommodation measures. Internal interviewees highlighted that it would have been beneficial to allocate sufficient time for planning, staff training, and to become acquainted with the recipient groups before initiating the distribution of funds (see Timeline, in Annex B). Additionally, a well-planned program with suitable terms and conditions would have been advantageous instead of changing them mid-delivery, which caused some internal strain.

Time for engagement

Collaborative development with Indigenous groups can be a lengthy process. Conversations and working together are necessary, but they can take time. As a time-limited initiative, SSI and AHRF faced challenges. Creating unique delivery models for Indigenous groups requires more time to develop. AHRF, for instance, required more time to collaboratively develop funding delivery models with Indigenous partners, but it was necessary to ensure its success. During the first year of SSI, there was limited time available for collaborative development. The same applies to the ALF, which is co-developed but required a considerable amount of time and resources for both DFO and Indigenous groups to discuss.

Sunsetting

SSI and AHRF are time-limited accommodation measures, originally scheduled to sunset in 2023-24, and extended by one year to 2024-25. Half of the groups who provided input into the evaluation are feeling frustrated and concerned about the sunsetting of the funds. They expressed fear for their job security and were uncertain about the sustainability of their projects. They also shared concerns with having some of their work undone, for instance with the management of invasive species, when funding ends and they become unable to maintain current levels of resourcing. In addition, some AHRF groups chose to wait for their Phase 2 CAs before commencing work on their projects, making the March 2025 deadline even more challenging. The initial 5-year timeframe was deemed too short and unrealistic, with some groups the evaluation team spoke with emphasizing the need for a sustainable source of funding for habitat restoration, protection, and marine stewardship activities due to the need for constant monitoring and the expected lifespan of the TMX project.

Reporting

Both SSI and AHRF were contribution programs that required funding recipients to submit progress reports and year-end reports. These reports were to include expenses, products, and actual results. As SSI and AHRF teams understood that reporting can be a time-consuming and resource-intensive process, engagement teams worked closely with the Indigenous groups to make the process as straightforward as possible.

Despite changes being made to reduce the administrative burden on groups, some still found the reporting process onerous and time-consuming. A few representatives from Indigenous groups who contributed to the evaluation did not consider some of DFO's reporting requirements to be necessary, and they did not think that they provided substantial value. AHRF streamlined funding by utilizing agreements that followed the terms and conditions of other accommodation measures such as TCEI or SSI. However, there was still room for improvement in terms of developing a standardized or integrated approach to reporting for both SSI and AHRF.

Webinars

Although webinars were well-received, interviewees suggested areas for improvement, including more in-person options. Furthermore, Indigenous presenters, often burdened with additional tasks, would have appreciated having their efforts acknowledged and potentially compensated.

DFO staff challenges

While both SSI and AHRF were perceived to have the right expertise, they were seen as needing more staff. It is worth noting that for AHRF, there were only five engagement leads assigned to manage 115 groups in the Pacific region. In contrast, SSI had the same number of engagement officers working with 33 groups. The AHRF team had a limited internal capacity to engage and support a large number of Indigenous groups. The shortage of staff on the AHRF side was a barrier to more meaningful engagement with the groups.

This shortage also resulted in a backlog of proposals for Phase 2, as there were not enough community leads to review them. According to internal interviewees, AHRF was understaffed on the G&C side, leading to long processing delays for applications.

For SSI, although many Indigenous groups who participated in the evaluation shared positive feedback about the staff they worked with, a few experienced challenges due to SSI staff turnover. A few groups the evaluation team spoke with noted that turnover impacted their ability to build a strong rapport with SSI staff. Another group found it frustrating, for example, when they had to adapt their approach to reporting with each new staff member. The timelines associated with temporary funding were cited by a few internal interviewees as hindering DFO staff retention, and, by extension, the ability to develop agreements in a timely manner.

AHRF delays

The transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2 of AHRF was challenging, especially when it came to accessing the funds in a timely manner. However, changes to the delivery models helped to mitigate these challenges to some extent, although some concerns remained among the groups.

There was a significant level of interest in AHRF which led to a high number of applications. This created administrative challenges such as the review of proposals, negotiations of agreements, and approval of re-profiled funds. For instance, AHRF staff had to spend a considerable amount of time processing the components of the CAs. As a result, there were delays for the agreements to be finalized and funding to be delivered to the groups.

This led to project delays for many AHRF recipients, as the majority of groups were unable to initiate projects without first securing funding. At least one group noted that they missed months of activities while waiting for the funds to be disbursed. To mitigate this, AHRF sought an extension of the program for an additional year to provide DFO and Indigenous groups with more time.

Indigenous groups who provided input into the evaluation said that the availability and timelines of different funding types, such as Phase 1 capacity funding, and Phase 2 base, flex, and pooled funding, was somewhat challenging to navigate. While recipient groups were responsible for keeping track of these timelines, one group the evaluation team spoke with suggested providing a visual representation may have been beneficial to aid both short-term and long-term planning. Furthermore, TCEI and AHRF measures shared similar naming schemes but had different meanings, which may have led to confusion. Therefore, clear communication and distinction could have been provided between these two measures to ensure Indigenous groups had a clear understanding.

3.4.4 Factors that hindered success

The lack of or strained pre-existing relationships with DFO and the limited capacity of some groups hindered the success of SSI and AHRF. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters limited engagement opportunities with Indigenous groups.

Relationship with DFO

Prior to the accommodation measures, DFO had struggled with its pre-existing relationship with some Indigenous groups due to disagreements over fishing rights and restrictions. In the Ontario and Prairie region, DFO did not have any prior relationship with Indigenous groups. Some Indigenous groups were hesitant to engage in accommodation measures related to TMX due to the poor or lack of relationships with DFO. Meaningful engagement through SSI and AHRF provided an opportunity to address historical issues and encourage positive relationships.

Indigenous groups’ capacity

Some smaller indigenous communities have limited capacity due to remote locations, community size, connectivity, and administrative capabilities. SSI and AHRF also faced challenges in achieving participation from eligible groups due to some groups being busy with other competing priorities to commit to projects, as well as difficulties in reaching certain groups.

COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted planning and early implementation, as well as in-person engagement with many Indigenous groups. Indigenous groups also had to prioritize addressing the impacts of several extreme weather events, including floods and wildfires, over advancing their projects.

3.4.5 Factors that enabled success

The role of individuals within Indigenous communities, the amount of available funding, and the use of digital platforms were factors that enabled the success of SSI and AHRF.

Indigenous groups and community members

Some Indigenous communities hired people from both within and outside their communities to build their own teams that played a key role in the success of the SSI and AHRF initiatives. These individuals had various expertise and networking skills, including knowledge gained from western science and valuable traditional and land-based knowledge. The teams were passionate about their work and were determined to achieve both short-term and long-term results for their communities. They also displayed remarkable resourcefulness.

Funding

Groups mentioned that the amount of funding available was higher than previously seen and allowed them to do work that is typically quite costly, on a much larger scale – ultimately facilitating the success of the accommodation measures. The delivery model of AHRF was structured in such a way that it provided a base level of funding to all groups, irrespective of their capacity. Through SSI and AHRF funding, teams were built and staffed, in some cases from the ground up, and were trained through a myriad of knowledge and skills development opportunities required to do their work.

Digital tools

Due to the pandemic, videoconferencing tools (such as Zoom and Microsoft Teams) have become prevalent and provided opportunities for efficiency and regular meetings with groups. Digital platforms and tools increased networking opportunities among Indigenous groups and with external organizations such as NGOs.

3.4.6 Best practices and consideration for future programming

Several best practices were identified in the co-development of SSI and AHRF. These include having dedicated DFO engagement teams to engage with Indigenous communities, pivoting to digital tools, ensuring meaningful participation, allowing Indigenous groups to make decisions for themselves, and being flexible. For future programming, it is important to consider the amount of time and resources required for engagement with Indigenous groups.

Strong engagement teams

SSI and AHRF engagement teams played a key role in the success of program delivery. These teams were particularly well-suited for engagement roles and great care was taken in hiring the right people for these positions. The staff were found to be open to feedback, transparent in their communication, respectful, and easily accessible through various communication channels.

Lesson learned: Having dedicated well-suited engagement officers working with fewer files enables individual support and relationship-building with Indigenous groups.

Meaningful engagement

The co-developed SSI and AHRF structures (such as working groups and workshops) offered a great opportunity for learning and sharing information.

Lesson learned: To meaningfully engage with Indigenous groups, it is essential to have dedicated teams and develop multi-pronged efforts to actively listen to concerns and take action.

Pivot online to expand reach with groups

Hosting virtual webinar workshops and sub-regional online working groups was a success, as it meant an unlimited number of participants could join from various groups.

Lesson learned: A pivot to virtual engagement fostered good collaboration and relationship building. Virtual engagement has become an additional tool in DFO’s toolbox, alongside in-person engagement.

Allow groups to decide for themselves

For true co-development and collaborative planning, groups need to have autonomy to reflect their local interests and concerns.

Lesson learned: To cultivate a relationship of trust and flexibility with Indigenous groups, it is important to promote a sense of equality and autonomy among all partners involved.

Flexibility

DFO provided various funding options for Indigenous groups; AHRF tailor-made funding mechanisms for each region, while the funding mechanism selected for SSI was seen as challenging to navigate. Groups noted that SSI and AHRF were flexible in amending proposals and agreements if requested, and with respect to eligible activities.

Lesson learned: When supporting Indigenous groups, it is important to have flexibility in funding mechanisms, as each community has its own considerations and capacities.

Time for engagement

Collaborative development with Indigenous groups is a process that requires time and involves extensive conversations and collaboration to build and maintain meaningful relationships. As a result, SSI and AHRF, being time-limited initiatives, encountered certain challenges and delays.

Consideration for future programming: In designing a program with a collaboratively developed component, it is crucial to consider the significant amount of time and resources required for both DFO and Indigenous groups to engage in discussions and planning.

4.0 Annexes

Annex A: Methodology, limitations & mitigation strategies

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence, and the triangulation of data to mitigate, where possible, any methodological challenges and limitations. This approach was taken to establish the reliability and validity of key findings, and to ensure that conclusions were based on objective and documented evidence.

Interviews

The evaluation team conducted 39 interviews with 42 individuals, including 29 DFO staff members, three external interviewees, and 10 representatives from SSI and AHRF recipient groups from both the Pacific and the Ontario and Prairie regions. Interviews were conducted online via a videoconference platform and were structured to discuss a range of questions related to relevance, effectiveness, efficiency and delivery.

Members of the evaluation team also travelled to British Columbia to meet with representatives from three SSI and AHRF recipient groups. While conducting these site visits, the evaluation team had the opportunity to gather information on experiences with SSI and AHRF from 15 individuals. These discussions covered the same topic areas as the virtual interviews; however, they were more semi-structured in nature.

Limitations and mitigations:

Indigenous groups interact with DFO through a variety of forums and programs. It is possible that when answering some of the evaluation questions, some of our interviewees were encompassing opinions from other experiences with the department. The evaluation team mitigated this possibility by asking clarifying questions in interviews. The information gathered from interviews was triangulated with other lines of evidence.

Document and file review

The evaluation team reviewed internal documents and files to understand the context and background behind SSI and AHRF in relation to TMX and to help respond to all evaluation questions. This included policies, procedures, Terms of Reference, planning and priorities documents, meeting summaries, reports, and reviews.

Administrative and financial data

The evaluation team reviewed and analyzed three categories of administrative and financial data:

- Performance information profiles;

- Grants and contributions agreement tracking system (GCATS); and

- Other internal program sources used to track progress (i.e., SSI & AHRF dashboards, Deputy Minister reports, AHRF phase 1 and 2 trackers).

Limitations and mitigations:

Some discrepancies were found between program data spreadsheets and GCATS data. In this instance, the evaluation team used GCATS data for analysis, as the program confirmed the latter was more up-to-date. As well, data was triangulated from other sources of data to ensure reliability.

The accommodation measures were also ongoing as the evaluation was conducting data analysis. To align with data collected through other lines of evidence, the evaluation team examined data available up until June 2023, given that the interviews and document reviews reflected the status of the accommodation measures at that point in time.

Indigenous participation

As SSI and AHRF were developed to address the concerns of Indigenous groups, it was important that the evaluation team gather feedback from recipient groups on the relevance, delivery, efficiency, and effectiveness of the accommodation measures.

From March to May 2023, the evaluation team worked with the SSI and AHRF Indigenous engagement teams to inform groups of the opportunity to participate in the evaluation. The evaluation team invited feedback in the way that worked best for each group, including, but not limited to, virtual interviews, written responses, recorded site tours, photovoice submissions, and in-person site visits.

The evaluation team approached outreach to SSI and AHRF recipient groups differently and based on recommendations from the respective Indigenous engagement teams.

For SSI, the evaluation team attended one virtual workshop to present the evaluation and answer questions, and a call to participate was also circulated via an SSI e-newsletter. The SSI engagement leads also followed up by email with groups and introduced those interested to the evaluation team via email.

With AHRF, the evaluation team attended one virtual workshop to inform groups about the evaluation and to invite participation. Following the presentation, the AHRF engagement leads recommended the evaluation team circulate a brief survey to gauge interest. Such a survey was developed, and the evaluation team discussed participation by phone and email with interested groups.

Between June and August 2023, the evaluation team gathered feedback from groups who volunteered to participate in the evaluation. This included contributions gathered through eight virtual interviews with 10 representatives, one written submission, and three site visits where field observations were conducted, and in-person discussions were held. Combined engagement efforts resulted in representation of experience from 11 SSI and/or AHRF recipient groups. This included one group who received SSI funding, six groups who received AHRF funding, and four groups who received both SSI and AHRF funding.