Evaluation of the Salish Sea Initiative and the Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund

Evaluation summary

Summary of the Evaluation of the Salish Sea Initiative and the Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund

(PDF, 0.27 MB)

About the Accommodation Measures

The Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) project will twin the existing Trans Mountain pipeline, which transports crude oil and refined petroleum products from Edmonton, Alberta to refineries and terminals in British Columbia and Washington State. In 2019, the Government of Canada re-initiated a Phase 3 consultation process with Indigenous groups along the TMX project corridor. As a result, the Government developed eight accommodation measures to address the interests of potentially impacted Indigenous groups, including the Salish Sea Initiative (SSI) and the Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund (AHRF), led by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

Salish Sea Initiative (SSI)

SSI provided funding to 33 eligible Indigenous groups to enable them to increase their technical and scientific capacity to conduct research, monitoring, and stewardship activities to identify valued ecosystem components and monitor the cumulative effects of human activities on these ecosystem components over time, in the Salish Sea biozone. $114 million was budgeted between 2019 and 2025, including $91M in contribution funding. An additional $50 million in an Arm’s-Length Fund (ALF) will support longer-term cumulative effects projects, beyond 2025.

Aquatic Habitat Restoration Fund (AHRF)

AHRF was designed to increase capacity within eligible Indigenous groups to protect and restore aquatic habitats that may be impacted by the TMX project or by the cumulative effects of development. Funding is available to 129 Indigenous groups whose communities or traditional territories are within the Fraser River Watershed and inland watersheds along the TMX pipeline and shipping corridor in the Salish Sea. Funded projects support capacity-building activities (Phase 1) and Indigenous-led aquatic habitat restoration activities (Phase 2). $85.9 million is available between 2019 and 2025, including the delivery of $75 million in contribution funding.

About the evaluation

The evaluation covered the fiscal years 2019-20 to 2022-23 and was inclusive of DFO’s Pacific Region and Ontario and Prairie (O&P) Region. While the two accommodation measures were regionally led, the Programs Sector in the National Headquarters provided support, reporting, and oversight of both. The evaluation was designed to provide evidence on where the accommodation measures were working well, as well as to identify where improvements could be made. It included an assessment of the relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, and delivery of AHRF and SSI. The evaluation methodology included a document and file review, 39 interviews, financial and data analysis, and input was received from 11 Indigenous groups who participated voluntarily in the evaluation.

Key Findings

Relevance

SSI and AHRF are well-aligned with current federal and departmental priorities to support fulfilling the Government of Canada’s commitments with respect to the TMX and to work in partnership with Indigenous Peoples. SSI and AHRF addressed the interests of Indigenous groups related to marine stewardship and aquatic habitat restoration in areas that are a priority to them. They allowed each recipient group to define what is important and where efforts and resources should be focused.

Co-development

SSI co-developed many engagement mechanisms and deliverables, such as the Salish Sea Interactive Map, which created opportunities for Indigenous groups to network and share different approaches for marine stewardship. Over the course of the SSI program, various engagement mechanisms were co-created, such as SSI committees, webinars, surveys, and science sessions. DFO and eligible Indigenous groups are also co-creating the ALF through an initial investment of $50 million. AHRF’s Phase 2 delivery model was collaboratively developed with Indigenous groups from the outset. The collaborative approach responded to the groups’ engagement needs and aquatic restoration priorities and supported Indigenous groups in determining the way AHRF would be delivered in Phase 2. This process resulted in tailored funding mechanisms and project proposal assessment processes in each region.

Participation and results

At the departmental level, SSI is meeting its performance targets. The majority of eligible groups participated in SSI, with 31 out of 33 eligible First Nations participating.

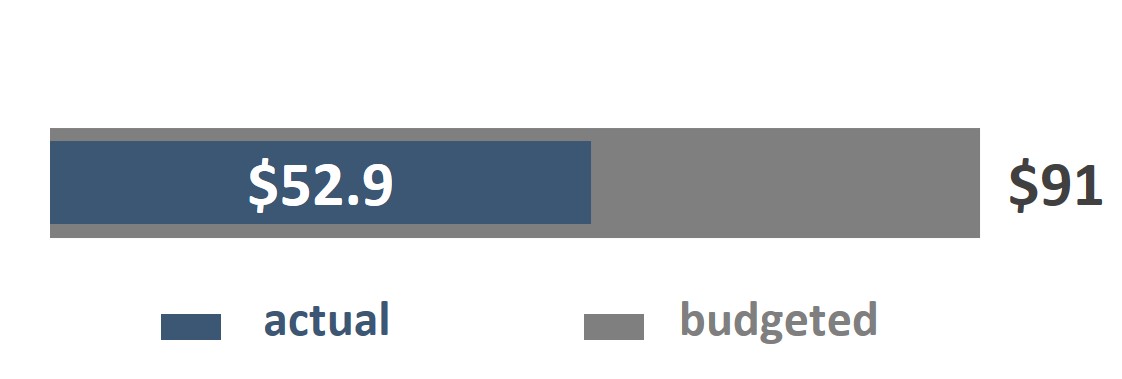

$52.9M (or 58%) had been disbursed under SSI as of June 2023, and $73M (or 80%) had been committed at that time. SSI continues to be on track to ensure delivery is on time and on budget by the March 2025 end date.

Figure 1 - Text version

This figure depicts the amount of SSI contribution funding that was disbursed by June 2023, totaling $52.9M, in comparison to the overall budget, totaling $91M.

AHRF was successful in providing capacity funding to 109 eligible Indigenous groups with contribution agreements in Phase 1 between 2020 and 2022, which has been disbursed.

AHRF faced challenges with the disbursement of project funding in Phase 2 to the 100 participating Indigenous groups. However, the extension of AHRF to March 2025 will provide additional time to ratify agreements, complete activities, and report on departmental outcomes.

Figure 2 - Text version

This figure depicts the number of AHRF-eligible Indigenous groups participating in Phase 1, based on region. There were 81 Indigenous groups in the Pacific region, and 28 in the O&P region.

Capacity Building

SSI and AHRF supported capacity building for Indigenous groups. Capacity built varied by group and SSI and AHRF supported groups to determine which activities to use to restore aquatic habitats and enhance marine stewardship within their territories. Through the measures, Indigenous groups invested in three key areas, including: human resources, training, and equipment and capital assets. Investments made allowed groups to build capacity necessary to carry out habitat restoration and stewardship activities that were meaningful to them and that had potential for positive impact on local ecosystems and communities. Groups also built the capacity to participate in decision-making, exchange knowledge, protect culture, provide outreach and education, and sustain the work into the future.

Key Findings

Efficiency and Delivery

The SSI and AHRF accommodation measures were well-resourced from the outset. Groups were provided with support to navigate funding processes, including proposals and contribution agreements. This resulted in a more efficient review and approval of projects.

The accommodation measures were flexible in terms of financial adjustments and in responding to unexpected events and delays. They were also broad in terms of eligible activities, allowing for the evolution of community priorities.

The delivery of an accommodation measure through a contribution program presented challenges and complexities. The sunsetting of the funds created frustration and concern amongst groups about job security and uncertainty around the sustainability of their projects. Despite changes being made to reduce the administrative burden on Indigenous groups, some still found reporting processes to be onerous and time-consuming.

The lack of or strained pre-existing relationships with some groups and/or the low capacity of some groups hindered the success of SSI and AHRF. Yet some external interviewees spoke to the positive impact that SSI and AHRF had on rebuilding relationships between involved Indigenous groups and DFO.

While the COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters limited engagement opportunities with Indigenous groups, the role of Indigenous internal teams, the volume of funding, and the use of digital platforms were factors that enabled the success of SSI and AHRF.

With regards to gender-based analysis plus considerations, SSI and AHRF were exclusively dedicated to potentially impacted Indigenous groups consulted in the context of the TMX project. Both SSI and AHRF tried to address challenges such as community remoteness, limited internet connectivity, and low community capacity.

Best Practices and Consideration for Future Programming

Best practices in co-development

- Strong engagement teams: Having dedicated, well-suited engagement officers working with fewer files enables individual support and relationship-building with Indigenous groups.

- Meaningful engagement: To meaningfully engage with Indigenous groups, it is essential to have dedicated teams and develop multi-pronged efforts to actively listen to concerns and take action.

- Pivot online to expand reach with groups: Virtual engagement has become an additional tool in DFO’s toolbox, alongside in-person engagement, to foster good collaboration and relationship building.

- Allow groups to decide for themselves: To cultivate a relationship of trust and flexibility with Indigenous groups, it is important to promote a sense of equality and autonomy among all partners involved.

- Flexibility: When supporting Indigenous groups, it is important to have flexibility in funding mechanisms, as each community has its own considerations and capacities.

Consideration for future programming

Collaborative development with Indigenous groups is a process that requires time and involves extensive conversations and collaboration to build and maintain meaningful relationships. In designing a program with a collaboratively developed component, it is crucial to consider the significant amount of time and resources required for both DFO and Indigenous groups to engage in discussions and planning.

- Date modified: