Thematic Evaluation of the Small Craft Harbours Program and DFO’s Jetties and Wharves

Final Report

January 2023

Thematic Evaluation of the Small Craft Harbours Program and DFO’s Jetties and Wharves

(PDF, 2.58 MB)

Table of Contents

- 1.0 Evaluation context

- 2.0 Departmental context

- 3.0 Evaluation findings

- 3.1 Summary of key findings

- 3.2 Relevance

- 3.3 Effectiveness

- 3.4 Efficiency

- 3.4.1 SCH funding mechanisms

- 3.4.2 RP funding mechanisms

- 3.4.3 Funding challenges

- 3.4.4 SCH and RP governance mechanisms

- 3.4.5 Information management for DFO's small craft harbours.

- 3.4.6 Information management for DFO's jetties and wharves

- 3.4.7 Performance measurement for DFO's small craft harbours.

- 3.4.8 Performance measurement of DFO's jetties and wharves

- 3.4.9 Asset management: prioritization of DFO's small craft harbours

- 3.4.10 Asset management: Prioritization of DFO's jetties and wharves

- 3.4.11 Asset management: Planning considerations for DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves

- 3.4.12 Asset Management: Divestiture of DFO's small craft harbours

- 3.4.13 Asset management: Recapitalization of DFO's jetties and wharves

- 3.4.14 Areas of mutual work

- 4.0 Conclusions and recommendations

- 5.0 Annexes

- Footnotes

1.0 Evaluation context

1.1 Purpose

An evaluation of Fisheries and Oceans Canada's (DFO's) Small Craft Harbours program and Jetties and Wharves was undertaken by the Department's Evaluation Division during fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23. The primary objective of the evaluation is to provide senior management with evidence-based information to support decision-making and the optimization of departmental resources related to small craft harbours, jetties and wharves. The evaluation complies with the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016) and meets the obligations of the Financial Administration Act.

1.2 Scope

The evaluation examined the relevance, effectiveness, and efficiency of activities related to DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves between 2016-17 to 2020-21. This includes elements of DFO's Small Craft Harbour (SCH) program and the departmental management of jetties and wharves by Real Property (RP). Perspectives from departmental users are also included in the scope of the evaluation, such as the Canadian Coast Guard as one of the main users of DFO's jetties and wharves.

1.3 Key Issues

The evaluation explores the extent to which:

- DFO's activities, structures, and processes are efficiently supporting service delivery for small craft harbours, jetties and wharves;

- Internal or external factors facilitate or hinder DFO's ability to deliver services related to small craft harbours, jetties and wharves; and

- DFO delivers services related to small craft harbours, jetties and wharves that are reliable, i.e., timely, accessible, and current, where:

- Timely refers to DFO's ability to plan, acquire, operate, maintain, and divest/dispose of assets at a level that ensures they are available to support program delivery;

- Accessible refers to DFO's ability to ensure that assets are safe and barrier-free; and

- Current refers to DFO's ability to manage assets in a manner that addresses the department's current and anticipated future needs.

1.4 Methodology

The evaluation was designed to respond to the questions listed in Table 1. To address the evaluation questions, information was triangulated from multiple lines of evidence including interviews, document and literature review, financial and administrative data analysis, a survey of DFO staff and external stakeholders, and case studies. Evaluation methodologies, limitations and mitigation strategies are discussed in Annex A.

Evaluation Questions

- What needs are DFO's small craft harbours program, and jetties and wharves addressing?

- How are these needs evolving?

- To what extent is DFO delivering services related to small craft harbours, jetties and wharves that are reliable (i.e., accessible, current and timely)?

- To what extent are DFO's activities, structures and processes efficient to support the service delivery of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves?

- What factors (internal or external to DFO) have facilitated or hindered DFO's ability to deliver services related small craft harbours, jetties and wharves?

- What factors (internal or external to DFO) could facilitate or hinder DFO's ability to deliver services related small craft harbours, jetties and wharves in the future?

- Are there best practices and/ossons learned that could help improve DFO's delivery of services related to small craft harbours, jetties and wharves?

- To what degree have GBA+Footnote 1 considerations been integrated into the management of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves?

2.0 Departmental context

DFO's network of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves are operated across unique departmental contexts.

DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves serve distinct purposes

Small craft harbours play a vital role in meeting the needs of the commercial fishing industry by providing a safe place for commercial harvesters and fishing boats.

Jetties and wharves serve internal purposes and are essential to the operations of departmental user groups. Wharves are platforms constructed for the berthing of client ships while jetties are typically narrow structures that extend into bodies of water to block flow of water and protect harbours and/or wharves.

DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves are managed by distinct departmental custodians

Small Craft Harbours (SCH) is a nationwide program managed by DFO that operates and maintains a network of harbours critical to the fishing industry, ensuring that they remain open and in good repair. These harbours provide commercial fish harvesters and other harbour users with safe and accessible facilities. The program is decentralized with headquarters located in Moncton, New Brunswick providing national coordination to five regional offices that manage operations.

Real Property is corporate real estate organization that manages jetties and wharves on behalf of DFO. Management occurs via a National Centre of Expertise (including Real Property and Environment Management (RPEM)) and 6 Regional Centres of Expertise (including Real Property, Safety and Security (RPSS)) that provide strategic and operational services in support of CCG and DFO programs. To avoid confusion, RPEM/RPSS will hereafter be collectively referred to as Real Property (RP).

DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves have similar engineering components

Because both the SCH Program and RP custodians manage marine engineered assets, there are similarities with regards to the asset management processes and terminology that are used across custodians. These similarities provide an opportunity to share good practices and lessons learned, where relevant, for the management of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves which share similar engineering components and were the reasons for conducting a thematic evaluation.

Differences across custodial objectives and service delivery models are nevertheless important to recognize. For instance, the SCH program and RP differ in theigislative obligations, mandates, results, activities, users and partners, asset portfolios, funding mechanisms, governance mechanisms and asset management processes, as discussed in the following sections.

2.1 Mandates

Small Craft Harbours Program

The SCH's program mandate is to maintain a critical and affordable national network of safe and accessible harbours that meets the principal and evolving needs of the commercial fishing industry, while supporting the broader interests of coastal communities and Canada's national interests. These harbours will be fully operated, managed and maintained by viable professional and self-sufficient harbour authorities representing the interest of local users and communities.

Real Property

RP's mandate is to ensure the accommodation of departmental programs through the provision of the department's real property (including jetties and wharves among other assets) in each region. RP provides leadership and expertise in real property planning, strategic investment, divestiture, infrastructure life-cycle management, facilities maintenance, environmental management, and employee safety and security advisory services.

2.2 Clients and user groups of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves

Small craft harbours serve the following user groups:

- Commercial fishing & marine industry – Small craft harbours provide protection for fishing vessels and equipment for the commercial fishing industry. They also offer support to many other businesses in the maritime sector, including fish processing, transportation, commercial recreational operations, aquaculture and tourism.

- Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) – Small craft harbour facilities may be co-located with CCG facilities, such as search and rescue stations. CCG may make also make limited use of other SCH facilities under extenuating circumstances or for transit stops or shelter.

SCH services are delivered in partnership with Harbour Authorities:

- Harbour Authorities (HA's) are incorporated, not-for-profit partner organizations that manage, operate, and maintain public fishing harbours on behalf of the SCH program through lease agreements.

Jetties and wharves serve the following departmental user groups:

- Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) – The CCG is the primary departmental user of DFO's jetties and wharves, which are used primarily for berthing during operations, to load and offload materiel and personnel, and/or to conduct repairs. Within the CCG, programs such as Fleet and Maritime Services, Environmental Response, Search and Rescue, and the CCG College make use of these departmental assets. Integrated Technical Services also requires wharf access to vessels to carry out maintenance and repair work.

- DFO – DFO programs also make use of departmental jetties and wharves. Users include but are not limited to: Conservation and Protection, Science, and the Canadian Hydrographic Service.

2.3 Management activities

SCH management activities include:

- Harbour maintenance ― The program assesses the physical condition of harbours and prioritizes funding for repairs;

- Harbour administration and support ― The program promotes the formation of Harbour Authorities (HA's) and provides guidance and tools aimed at helping HA's develop the management, governance, and planning expertise needed to efficiently administer harbours; and

- Harbour disposal ― The program reduces its infrastructure footprint by focusing on core fishing harbours (those essential to the commercial fishing industry) and removing non-core harbours (those with recreational or low fishing activity that are non-essential to the commercial fishing industry) by divesting to third parties or disposing of them and restoring habitat as required.

RP management activities include:

- Planning – RP carries out planning activities in accordance with Departmental objectives, program requirements, asset information, and compliance and reporting requirements;

- Life-cycle management– Life-cycle management refers to the management of investments along a continuum starting with asset planning, acquisition, use and maintenance, and ending with asset disposal, divestment or close-out.Footnote 2 RP undertakes life-cycle management for jetties and wharves as part of a larger engineering asset portfolio;

- Maintenance – RP carries out maintenance and upkeep of jetties and wharves and ensures that they meet the requirements of departmental users.

2.4 Legislation

While SCH and RP both manage assets on behalf of the federal government, their respective asset management processes are guided by unique suites of policies and regulations:

- The Fishing and Recreational Harbours Act enables the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans to acquire, contribute to, maintain, operate and repair fishing and recreational harbour facilities across Canada.

- Broadly, the management of RP is guided by the Treasury Board (TB) Policy on the Planning and Management of Investments (2021), including the Directive on the Management of Real Property (2021).

2.5 Departmental/custodial results

The SCH program is an established program in DFO's Departmental Results Framework (DRF) and aligns directly to the following:

- Core responsibility: Fisheries.

- Ultimate outcome: Safety and security.

- Departmental result: The commercial fishing industry has access to safe harbours.

RP is a corporate real estate organization that provides internal services to the department. As such, RP is not tied to a specific core responsibility or result in DFO's Departmental Results Framework (DRF). Rather, they support the results and objectives of their departmental clients as an internal service.

2.6 Asset portfolio

The SCH program oversees a network of 973 harbours across Canada. This network includes:

- 675 core harbours which are critical to the commercial fishing industry and managed by HA's; and

- 298 non-core harbours which have low rates of fishing activity and may mainly serve recreational purposes.

Both core and non-core harbours consist of a variety of facilities (such as wharves, water lots, breakwaters, shore facilities and electrical, sanitary, and fire prevention systems) for which the program is responsible.

RP manages 269 assets within a national portfolio. This portfolio includes jetties and wharves as well as facilities such as hatcheries, laboratories, light stations and boathouses. The national portfolio is divided into six site categories, of which wharves and jetties fall into Category 1, 2, and 6.

- Category 1 and 2 sites are broader sites that include jetties and wharves, for instance bases, laboratories, specified major facilities, CCG college training facilities, search and rescue stations, and lighthouses; and

- Category 6 sites are sites that include marine-based infrastructure, such as wharfs.

2.7 Regional distribution

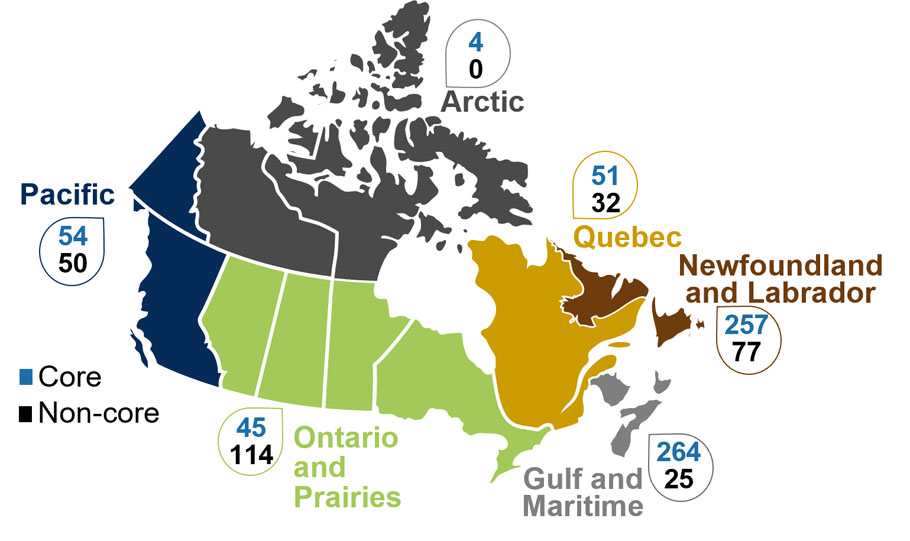

Small craft harbours are distributed across DFO regions, with the majority of core harbours centralized in Newfoundland and Labrador and the Gulf and Maritime Region. Most non-core harbours are located in the Ontario and Prairies region (Figure 1).

Description

The figure depicts the distribution of core and non-core small craft harbours located across Fisheries and Oceans Canada regions. In the Arctic region, there are 4 core and 0 non-core harbours. In the Quebec region, there are 51 core harbours and 32 non-core harbours. In the Newfoundland and Labrador region, there are 257 core harbours and 77 non-core harbours. In the Gulf and Maritime region, there are 264 core harbours and 25 non-core harbours. In the Ontario and Prairies region, there are 45 core harbours and 114 non-core harbours. In the Pacific region, there are 54 core harbours and 50 non-core harbours.

RP sites containing jetties and wharves are located across CCG regions. Category 1 and 2 sites are mostly located in the Western, Central, and Atlantic regions while Category 6 sites are located in the Arctic and Atlantic (Figure 2).

Description

The figure depicts the distribution of category 1 and 2 as well as category 6 sites located across Canadian Coast Guard regions. In the Arctic region there is one category 1 and 2 site, as well as 47 category 6 sites. In the Atlantic region, there are 17 category 1 and 2 sites, as well as 25 category 6 sites. In the Central region, there are 32 category 1 and 2 sites, as well as one category 6 site. In the Western region, there are 20 category 1 and 2 sites, and 2 category 6 sites.

2.8 Financial context

SCH's financial profile is composed of A- and B-base funding authorities

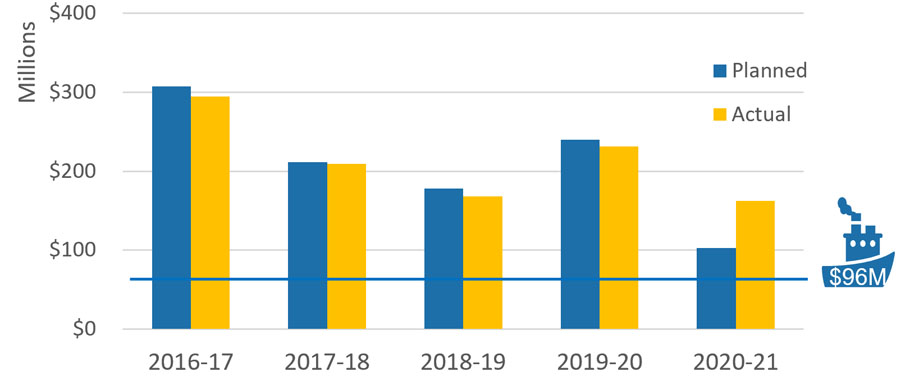

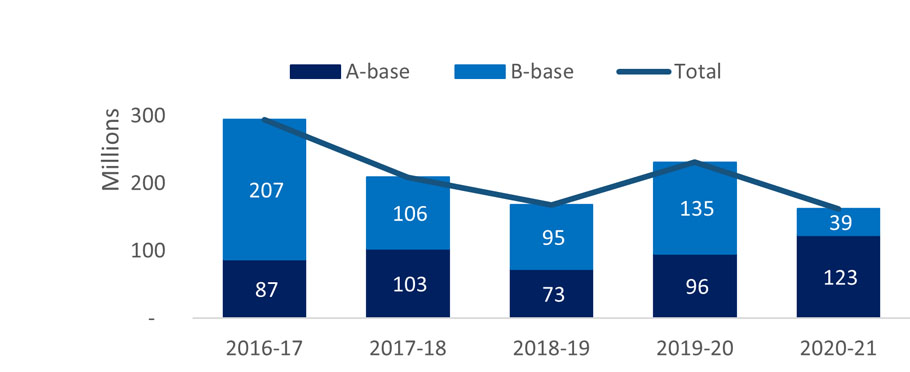

During the scope of the evaluation, SCH's annual budget decreased from $307M in 2016-17 to $102M in 2020-21. During this time, the program received $96M per year in A-base permanent funding, on average (Figure 3). Annual planned expenditures beyond this stable A-base budget are a result of periodic B-base funding augmentations. B-base authorities are time limited and/or temporary, for example:

- Budget 2015 provided $288.1 million over two years for improvements to core harbour and to address liability issues at non-core harbours;

- Budget 2016 provided $148.6 million over two years for the repair and maintenance of core harbours;

- Budget 2017 provided $5 million for the repair and maintenance of core harbours; and

- Budget 2018 provided $250 million for the repair and maintenance of core harbours and to accelerate the divestiture of non-core harbours.

Description

The figure depicts the planned and actual expenditures of the Small craft Harbour program between fiscal year 2016-17 and 2020-21. In fiscal year 2016-17, the program had planned expenditures of $307M and actual expenditures of $294M. In fiscal year 2017-18, the program had planned expenditures of $211M and actual expenditures of $209M. In fiscal year 2018-19, the program had planned expenditures of $178M and actual expenditures of $168M. In fiscal year 2019-20, the program had planned expenditures of $240M and actual expenditures of $231M. In fiscal year 2020-21, the program had planned expenditures of $102M and actual expenditures of $162M.

The figure notes that during this time the SCH program received $96M per year in permanent A-base funding, on average. The figure also notes that planned expenditures do not reflect funds that SCH may receive throughout the year in addition to their A-base budget.

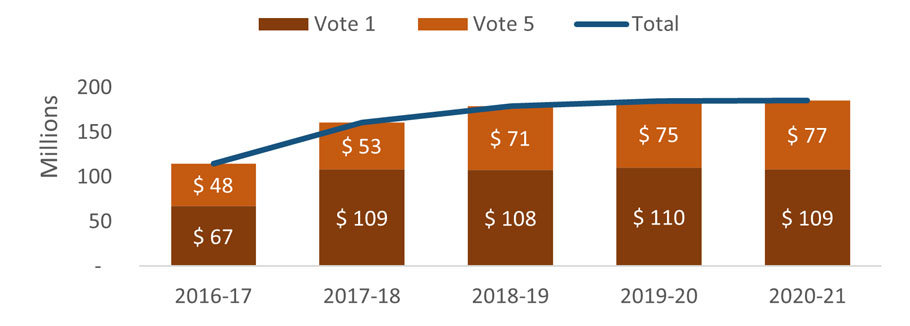

RP funding is composed of Vote 1 and Vote 5 funding authorities

Votes specify annual expenditure limits. Vote 1 funds are typically directed to day-to-day operating costs, such as salaries and utilities while Vote 5 funds are typically directed to capital expenditures and used to acquire capital assets that have continuing use, such as buildings and wharves.

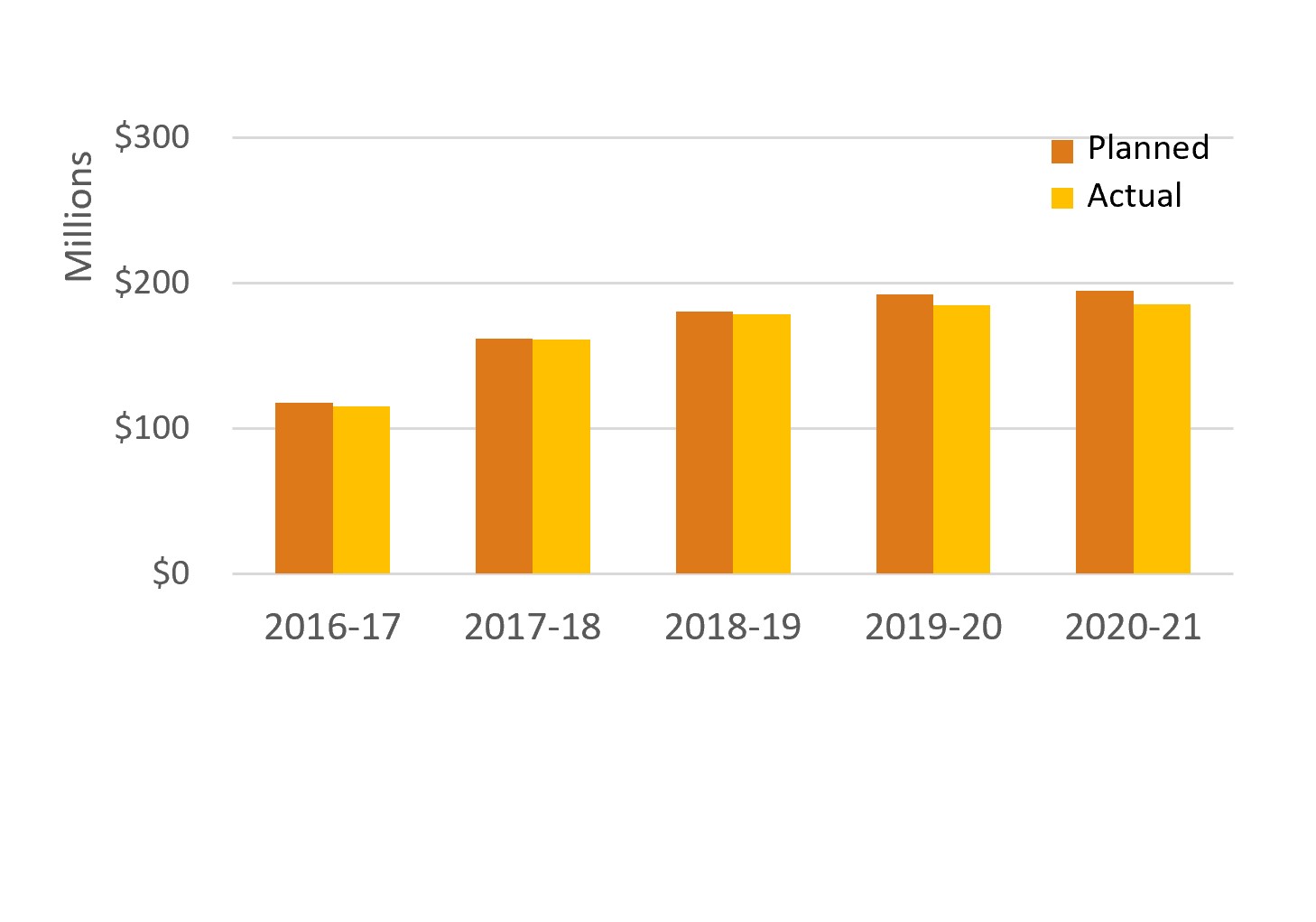

Because RP's national portfolio is segmented using a site model rather than specific asset categories, financial information that is specific to jetties and wharves is not available. During the scope of the evaluation, RP's planned expenditures for the management of the overall national portfolio increased from $117M in 2016-17 to $195M in 2020-21.

Description

The figure depicts Real Property's planned and actual expenditures between fiscal year 2016-17 and fiscal year 2020-21. In fiscal year 2016-17, Real Property had planned expenditures of $117M and actual expenditures of $115M. In fiscal year 2017-18, Real Property had planned expenditures of $162M and actual expenditures of $161M. In fiscal year 2018-19, Real Property had planned expenditures of $180M and actual expenditures of $178M. In fiscal year 2019-20, Real Property had planned expenditures of $192M and actual expenditures of $185M. In fiscal year 2020-21, Real Property had planned expenditures of $195M and actual expenditures of $185M.

3.0 Evaluation findings

3.1 Summary of key findings

Relevance

- There are ongoing needs for small craft harbours, jetties and wharves which are evolving as the needs of target user groups and Government of Canada priorities evolve.

- The management of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves is aligned with DFO, CCG, and Government of Canada priorities.

Effectiveness

The evaluation focuses on three characteristics of service delivery to assess the effectiveness of service delivery at small craft harbours, jetties and wharves:

- Timely refers to DFO's ability to plan, acquire, operate, maintain, and divest/dispose of assets at a level that ensures they are available to support program delivery;

- Accessible refers to DFO's ability to ensure that assets are safe and barrier-free; and

- Current refers to DFO's ability to manage assets in a manner that addresses the department's current and anticipated future needs.

The evaluation found that small craft harbour, jetty and wharf services are generally delivering services that are reliable. The degree of reliability varies among target user groups.

Efficiency

The evaluation presents findings relevant to the efficiency of inputs underlying the asset management process, such as funding mechanisms, governance mechanisms and information management mechanisms which also differ between custodians.

- Funding mechanisms: Departmental funding mechanisms face a number of hindering factors, both now and into the future. These include, but are not limited to, changing regulatory requirements, increased maintenance expenses, and challenges with procurement, and are therefore not considered to be sustainable in the future.

- Governance mechanisms: Governance structures are generally appropriate to support the management of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves.

- Information management: The availability of operational data that is specific to DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves can be improved to better support decision-making.

- Performance measurement: Performance data for the SCH program indicates that performance targets are being met. However, there is a need for program results and indicators that can tell an accurate performance story with regards to the SCH asset portfolio in the long-term.

- Asset management:

- Prioritization: There are internal and external factors affecting custodians' ability to prioritize the asset management of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves.

- Planning considerations: SCH and RP custodians incorporate environmental considerations in the planning, activities, structures, and processes that support service delivery. There are opportunities to increase awareness of how GBA+ principles apply to custodial functions.

- Disposal: There are varying degrees of disposal of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves within and across custodians. Disposal of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves is challenging due to their prohibitive cost.

- Areas of mutual work: Custodians indicated that planning processes are somewhat appropriate to ensure service delivery in the present day but will be less so in the future. There are opportunities to further develop areas of mutual work between the custodian groups.

3.2 Relevance

3.2.1 Ongoing needs for DFO's small craft harbours

There are ongoing needs for DFO's small craft harbours which are evolving beyond the program's mandate.

Ongoing needs among the program's target user groups are being met; however, the demand for harbour services is increasing and creating pressures on the program that lie outside its mandate.

Through Harbour Authority lease agreements, the SCH program provides critical support and high service standards to the commercial fishing industry. HA's agree that the ongoing needs of these target user group are being met. Nevertheless, the program's network of harbours remains a key driver for regional economic development and user needs for harbour services are evolving into broader ocean economy sectors beyond the program's mandate. New and emerging areas include:

- Diverse fisheries and aquaculture needs: Increased aquaculture activities are resulting in overcrowded harbours and leading user groups to compete for limited space. A reassessment of the SCH mandate may be needed to ensure services are provided to relevant industries to minimize the loss of economic opportunities.

- Recreational needs: Non-core harbours, which are more closely aligned with local tourism and recreational interests, are disposed of or divested by the program. In regions with a high number of non-core harbours, such as the Ontario and Prairies region, the SCH program faces difficulty in maintaining or divesting non-core harbours and thereby meeting the needs of recreational users.

- Increasing Indigenous participation in the SCH program (Annex B): Small craft harbours present opportunities for Indigenous Reconciliation as the program faces pressures to accommodate Indigenous fishing activities at existing harbours. A need was identified for greater clarity regarding mandate commitments related to services for Indigenous and remote communities.

- Need for harbour development in the North (Annex C): Ocean access is overarchingly important for Arctic communities for transportation, sustenance, maintaining livelihoods, and supporting existing/developing commercial fishing industries. However, harbours are lacking in many northern communities whose needs are not being met by the program. Harbour development in the north can contribute to the Reconciliation Agenda as mechanisms to address the historic lack of investments in the North. The need for harbour development in the north, including challenges, is further discussed in Annex C.

Most SCH staff (73%) and a majority of HA survey respondents (88%) indicated that small craft harbours were meeting the ongoing needs of commercial fishers between a moderate and great extent.

In addition:

- Some HA respondents (47%) indicated the needs of the aquaculture industry were being met to a moderate and great extent;

- Some HA respondents (36%) indicated the needs of recreational fishers were being met to a moderate and great extent;

- Most HA respondents (53%) indicated the needs of non-commercial Indigenous fishers were being met to a moderate and great extent; and

- Most HA respondents (64%) indicated the needs of the local harbour communities were being met to a moderate and great extent.

3.2.2 Ongoing needs for DFO's jetties and wharves

While the needs of departmental users are somewhat being met, there are additional ongoing needs for DFO's jetties and wharves which are evolving as the needs of departmental user groups and GoC priorities evolve.

Ongoing needs for DFO's jetties and wharves are driven by the operational requirements of departmental clients and user groups whose needs are evolving.

Departmental users of jetties and wharves include CCG and DFO programs. Overall, the evaluation found that the needs of departmental users are somewhat being met, with CCG interviewees indicating that maintenance and repairs required at certain sites pose a risk to their ability to carry out operations (further details in section 3.3.2). If the CCG is unable to conduct operations, neither can DFO and CCG programs that depend on the availability of ships and supporting infrastructure. Nevertheless, DFO is the main provider of jetty and wharf services as other federal departments with similar assets are divesting of them. Therefore, there is an ongoing need to meet users' evolving operational requirements as DFO, CCG, and GoC priorities evolve. These include:

- Increasing infrastructure needs as the number and size of vessels increases: Increased berthage needs are a result of Canada's National Shipbuilding Strategy, which involves the construction of more than 60 new vessels of the CCG, DFO, and the Royal Canadian Navy. The CCG's Fleet Renewal Plan will also renew CCG's large vessel fleet with up to 16 Multi-Purpose Vessels, six program icebreakers, and two Arctic Offshore Patrol Vessels.

- Increasing infrastructure needs related to fleet modularity: CCG's fleet renewal will implement mission modularity using multipurpose vessels that are adaptable to mission specific equipment. For instance, modules could store emergency response equipment in remote locations, operate portable science labs and equipment on CCG ships, and provide secure storage for conservation and protection. Infrastructure requirements, such as minimum wharf space and loading area requirements at key locations will need to be determined.

- Need for climate resilient infrastructure: In the face of climate change, there is a need to ensure that harbours are adapted to the impacts of climate change. To this effect, DFO is committed to transitioning to low-carbon, climate resilient, and greener operations under the Greening Government Strategy. The SCH program has incorporated climate change impact planning and modeling tools such as an infrastructure vulnerability index and the Canadian extreme watevel adaptation tool. While RP is aware of these tools, they are working on expanding their use.

Most RP (64%) and CCG (56%) respondents and some DFO (36%) respondents indicated that DFO's jetties and wharves were meeting their operational needs to a moderate and great extent.

In addition:

- Few CCG (20%) and DFO (16%) survey respondents indicated that their operational needs are evolving as a result of changing vessel strategies;

- Some CCG (28%) and DFO (29%) survey respondents indicated that their operational needs are evolving as a result of changing vessel requirements;

- Few CCG (16%) and DFO (4%) survey respondents indicated that their operational needs are evolving as a result of changing GoC priorities; and

- Few CCG (7%) and DFO (16%) survey respondents indicated that their operational needs are evolving as a result of changing DFO/CCG priorities.

3.2.3 Government of Canada and DFO priorities are evolving

The management of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves is aligned with DFO, CCG, and Government of Canada priorities.

Small Craft Harbours

- Marine Conservation Targets

- Blue Economy Strategy

- DFO mandate letter commitments, which support improvements in SCH to ensure infrastructure serves the needs of the fishing industry and local residents.

Real Property

Both Small Craft Harbours and Real Property:

Box A. The Greening Government Strategy

The Greening Government Strategy focuses on four areas: fleet and mobility, property and workplace, climate-resilient services and operations, and the procurement of goods and services. Under this strategy, SCH and RP custodians are adapting to a green innovation model in the design of ship and shore infrastructure that employs renewable, sustainable, and energy-efficient solutions both onboard and onshore. Best practices implemented by the SCH program include the use of innovative technologies and new materials such as low carbon concrete, plastic wood decking made from recycled materials, purchasing buildings made from recycled plastic, and LED and solar lights. Pilot projects have also been implemented to:

- Reuse dredged material and mix dredging with compost to reduce contamination;

- Incorporate living breakwaters that use rock and natural vegetation to improve ecosystems; and

- Consider zonal planning to reduce the program's coastal footprint by consolidating multiple smaller harbours into one large harbour.

Requirements for DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves are evolving

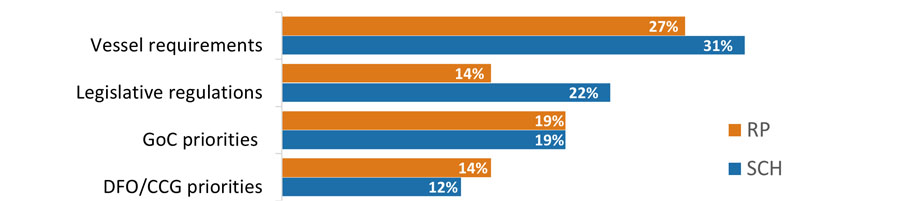

SCH and RP custodians indicated that changing vessel requirements, legislative regulations, GoC priorities, and DFO/CCG priorities are driving the evolution of user needs (Figure 5).

Description

The figure depicts various drivers of evolving user and operational needs for Real Property and the Small Craft Harbours program. For instance, 27% of Real Property and 31% of Small Craft Harbour staff indicated that changing vessel requirements are driving the evolution of user needs; 14% of Real Property and 22% of Small Craft Harbour staff indicated that changing legislative regulations are driving the evolution of user needs; 19% of Real Property and Small Craft Harbour staff each indicated that changing Government of Canada priorities are driving the evolution of user needs; and 14% of Real Property and 12% of Small Craft Harbour staff indicated that changing Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Canadian Coast Guard priorities are driving the evolution of user needs.

3.3 Effectiveness

3.3.1 Reliability of DFO's small craft harbours

Overall, SCH mostly delivers services that are reliable, meaning that key informants and survey respondents indicated they were mostly timely, accessible, and current.

Small craft harbour services at core harbours are mostly timely, accessible, and current

Timely: The ability of the SCH program to deliver timely services at core harbours depends on a number of challenges that will be discussed throughout the report, such as the program's ability to carry-out long-term planning, respond to staffing pressures, meet increasing demands for core harbours in the Arctic, and divest of non-core harbours. SCH interviewees rated timeliness between some and a moderate extent, on average.

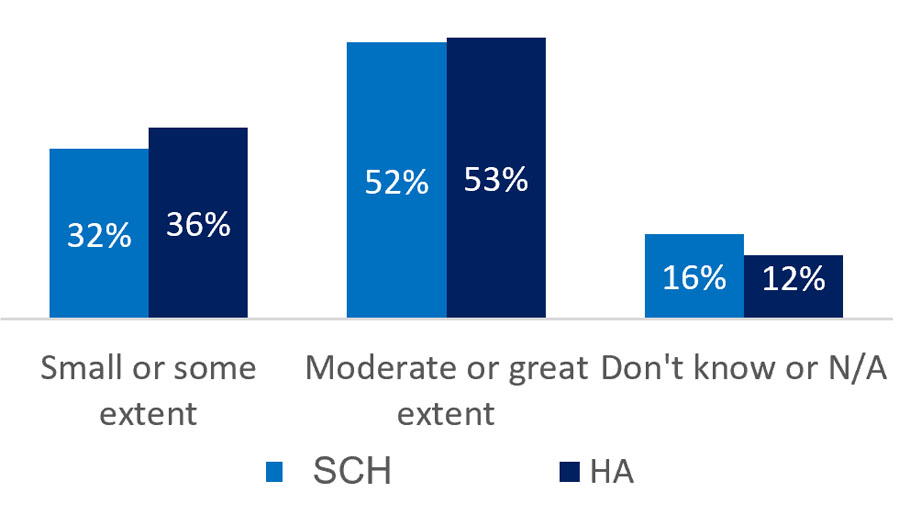

Description

The figure depicts the extent to which Small Craft Harbour program staff and Harbour Authorities consider small craft harbour services to be timely. For instance, 32% of program staff and 36% of harbour authorities indicated that services were timely from a small to some extent; 52% of program staff and 53% of harbour authorities indicated that services were timely from a moderate to a great extent; and 16% of program staff and 12% of harbour authorities indicated that they did not know to what extent small craft harbour services were timely, or that it did not apply to them.

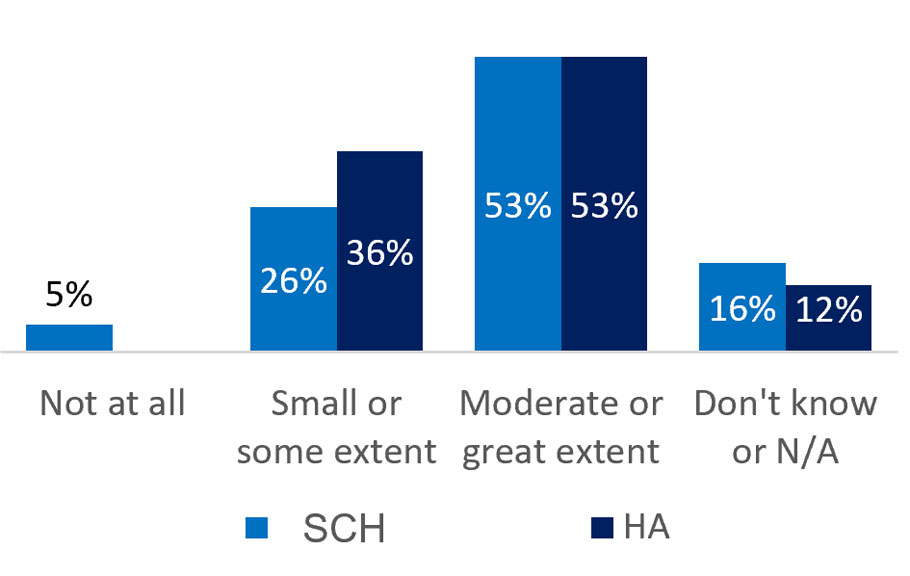

Accessible: Interviewees indicated that ensuring the safety of core harbours is a program priority. The continued use of unsafe sites represents a liability and risk to the department, therefore ensuring harbour safety is at times accomplished by limiting public access and the fishing viability of core harbours. SCH interviewees rated accessibility between a moderate and great extent, on average.

Description

The figure depicts the extent to which Small Craft Harbour program staff and Harbour Authorities consider small craft harbour services to be accessible. For instance, 5% of program staff indicated that services were not at all accessible; 26% of program staff and 36% of harbour authorities indicated that services were accessible from a small to some extent; 53% of program staff and 53% of harbour authorities indicated that services were accessible from a moderate to a great extent; and 16% of program staff and 12% of harbour authorities indicated that they did not know to what extent small craft harbour services were accessible, or that it did not apply to them.

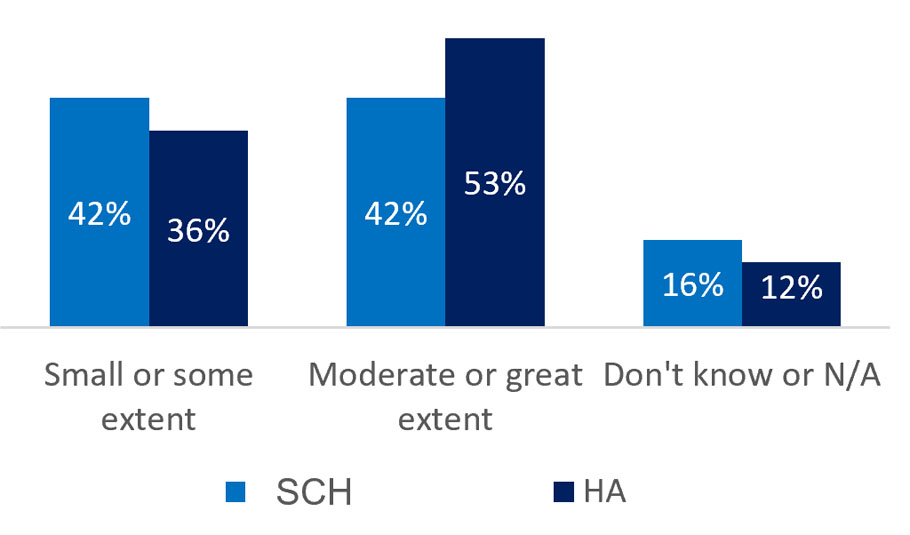

Current: Delivering services at core harbours that are current depends on the program's ability to carry out strategic long-term planning for infrastructure that adapts and responds to evolving client needs, including needs for climate change innovations and multi-purpose harbours. SCH interviewees rated services being current between some and a moderate extent, on average.

Description

The figure depicts the extent to which Small Craft Harbour program staff and Harbour Authorities consider small craft harbour services to be current. For instance, 42% of program staff and 36% of harbour authorities indicated that services were current from a small to some extent; 42% of program staff and 53% of harbour authorities indicated that services were current from a moderate to a great extent; and 16% of program staff and 12% of harbour authorities indicated that they did not know to what extent small craft harbour services were current, or that it did not apply to them.

HAs generally had a positive outlook on their ability to deliver reliable services at their respective harbours. However, in some regions HAs indicated that services are not timely or accessible when harbours are barricaded due to unsafe conditions or when dredging does not take place as this impacts the physical accessibility of harbours by boats at sea.

3.3.2 Reliability of DFO's jetties and wharves

Overall, RP delivers jetty and wharf services that are somewhat reliable, meaning that key informants and survey respondents indicated they were somewhat timely, mostly accessible, and somewhat current.

Real Property delivers services that are somewhat timely

The timeliness of jetty and wharf services varies depending on factors that affect RP's ability to manage the lifecycle of these assets, for instance:

- The availability of capital funding for repair and maintenance projects;

- The lengthy planning (i.e., contracting and conducting engineering studies) and implementation timeframes that are required; and

- RP's knowledge of current and evolving user needs (i.e., related to climate resiliency), as these can evolve faster than infrastructure changes can be implemented.

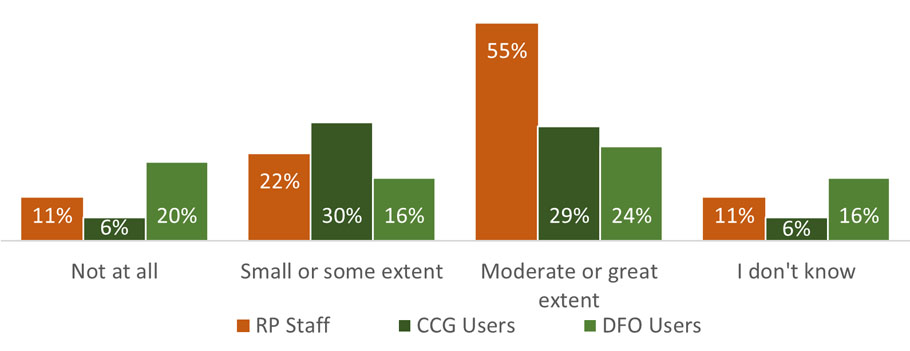

As a result, the timeliness of jetty and wharf services varies across RP sites, with some sites experiencing serious degradation. When services are not timely, DFO (Box B) and CCG (Box C) users reported facing significant challenges carrying out their respective mandates.

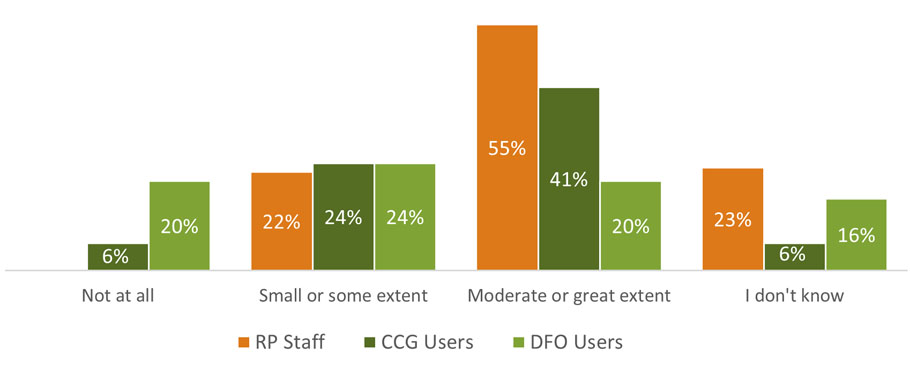

Description

The figure depicts the extent to which Real Property, Canadian Coast Guard and Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff consider jetty and wharf services to be timely. For instance, 11% of real property, 6% of Canadian coast guard and 20% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were not at all timely; 22% of real property, 30% of Canadian coast guard and 16% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were timely to a small or some extent; 55% of real property, 29% of Canadian coast guard and 24% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were timely to a moderate or great extent; and 11% of real property, 6% of Canadian coast guard and 16% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that they did not know to what extent small craft harbour services were timely.

Box B. St. Andrew's Biological Station (SABS)

In early 2022, RP condemned the SABS wharf which supported CCG vessels, and in turn various DFO users carrying out science, fisheries management and aquatic ecosystems activities. The wharf is considered a non-operational asset within the operational St. Andrew's station. RP is in the process of replacing the wharf, but it is not expected to be operational for a number of years.

DFO respondents indicated that not having access to the wharf severely impacted their ability to deliver on their respective responsibilities and has led to significant impact to their activities. There was a lack of effective communication between RP and SABS user groups with respect to wharf closure decisions and alternative solutions. Therefore, while there have been efforts to find safe alternative berths for program ships, RP will continue to face challenges until a new wharf is built and operational.

Box C. Victoria Base

CCG respondents reported recurring issues and safety concerns at wharfs that have fallen into general disrepair in the Western region. At Victoria Base, for instance, half the wharf has been condemned and barricaded by RP to limit access. As a result, CCG users face significant logistical challenges with regards to moving cargo and carrying out resupply and refueling plans since the accessible section of the wharf does not meet length, loading capacity, power systems, or fendering requirements. This limits the type and timing of ships that can berth and was likened to “having an airplane but no airport”.

Wharf services at Victoria Base were not considered timely given that the need for wharf repairs has been known for many years and only temporary repairs have been realized thus far.

3.3.3 Reliability of jetties and wharves

Real Property delivers services that are mostly accessible

With regards to safety, RP interviewees indicated this is a major consideration driving the management of jetties and wharves, for instance sites deemed unsafe are barricaded to limit user access. Some regions have initiated Jetty Safety Programs that were highlighted as best practices.

CCG and DFO survey respondents raised concerns about elements of safety in the accessibility at each site as well as by ships at sea. Barriers to accessibility include a lack of readily available locations to conduct crew changes and equipment loading and insufficient funds to provide appropriate infrastructure. For example, the Maurice Lamontagne Institute in Quebec lacks a breakwater rendering the facility unusable under certain weather conditions. When jetties and wharves are not accessible, departmental users make use of public wharves where possible, particularly in remote areas.

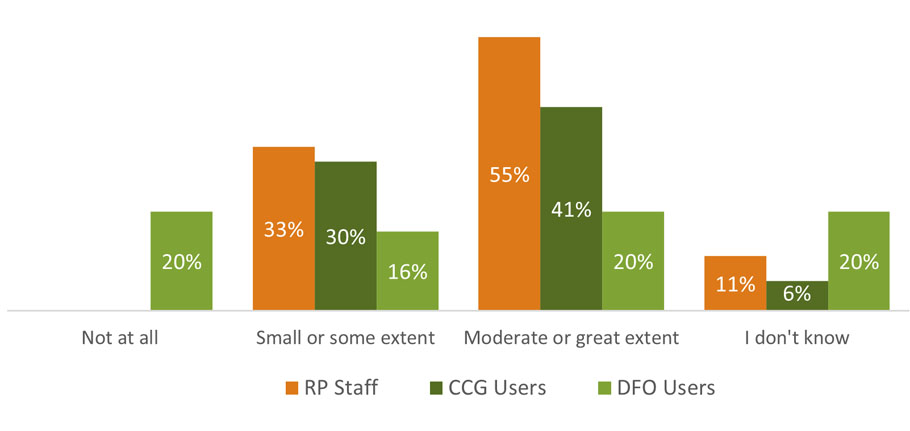

Description

The figure depicts the extent to which Real Property, Canadian Coast Guard and Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff consider jetty and wharf services to be accessible. For instance, 6% of Canadian coast guard and 20% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were not at all accessible; 22% of real property, 24% of Canadian coast guard and 24% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were accessible to a small or some extent; 55% of real property, 41% of Canadian coast guard and 20% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were accessible to a moderate or great extent; and 23% of real property, 6% of Canadian coast guard and 16% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that they did not know to what extent small craft harbour services were accessible.

Real Property delivers services that are somewhat current

RP's ability to provide jetty and wharf services that meet current and anticipated needs is impacted by the degree of investments required by these marine-based engineered assets as well as historical cuts in asset-specific spending. Another component affecting RP's ability to proactively deliver services is their knowledge of client's ongoing and evolving needs. While the needs of some clients are well known, others are evolving and require earlier client engagement to facilitate. Several measures have been implemented in recent years to improve communication and collaboration between RP and user groups such as the CCG, as discussed in section 3.4.10.

Description

The figure depicts the extent to which Real Property, Canadian Coast Guard and Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff consider jetty and wharf services to be current. For instance, 20% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were not at all current; 33% of real property, 30% of Canadian coast guard and 16% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were current to a small or some extent; 55% of real property, 41% of Canadian coast guard and 20% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that services were current to a moderate or great extent; and 11% of real property, 6% of Canadian coast guard and 20% of fisheries and oceans program staff indicated that they did not know to what extent small craft harbour services were current.

CCG interviewees indicated that many wharves are overdue for repair and cannot be used by the current fleet. Concerns remain that RP does not have a long-term plan to address wharf issues and the needs of the fleet of the future.

3.4 Efficiency

3.4.1 SCH funding mechanisms

The SCH program's reliance on temporary B-base funding creates significant challenges for planning lifecycle management in the long term. The program faces long-term funding shortfalls that will hinder future service delivery.

SCH funding mechanisms face long-term shortfalls relative to asset requirements for maintenance and repairs. This limits the custodian's ability to implement long-term solutions to maintain assets in optimal conditions on an ongoing basis

As mentioned in section 2.8, SCH's annual budget decreased from $307M in 2016-17 to $102M in 2020-21. Most of this funding envelope represents a high proportion of temporary B-base funding received through various Government of Canada budget announcements as opposed to permanent A-base program funding (Figure 12).

It is estimated that the SCH program experiences significant funding shortfalls to maintain all core fishing harbours facilities on an ongoing basis in better or fair condition. Under the current reliance on B-base funding, the program places priority attention on essential safety repairs, maintenance, dredging, and other urgent investments at core-harbours. Without the significant B-base funding over the last decade, SCH would have had to take safety related measures at a significant number of sites such as instituting load restrictions, setting up barricades or removing unsafe facilities.

The program's reliance on temporary B-base funding poses significant challenges for the lifecycle management of small craft harbours because staff lack consistent stable funding and must instead deliver across short, two-year, funding cycles. Funding challenges will be discussed throughout the report and include:

- Planning upcoming work, including adapting to increased maintenance expenses and securing contracting and procurement;

- Staff retention; and

- Telling an accurate results story using short term performance indicators associated with temporary funding commitments.

Description

The figure depicts how the Small Craft Harbour program's expenditures, including A and B-base funding, have decreased between fiscal year 2016-17 and 2020-21. In fiscal year 2016-17, total program expenditures consisted of $207M in B-base funds and $87M in A-base funds. In fiscal year 2017-18, total program expenditures consisted of $106M in B-base funds and $103M in A-base funds. In fiscal year 2018-19, total program expenditures consisted of $95M in B-base funds and $73M in A-base funds.

In fiscal year 2019-20, total program expenditures consisted of $135M in B-base funds and $96M in A-base funds. In fiscal year 2020-21, total program expenditures consisted of $39M in B-base funds and $123M in A-base funds.

Across the 5 years, only 45% of SCH program expenditures came from A-base permanent funding sources while B-base sources of funding accounted for 55% of total program expenditures.

3.4.2 RP funding mechanisms

RP faces significant funding shortfalls that hinder their ability to manage the lifecycle of jetties and wharves. In part, this is due to the design of RP's national portfolio strategy relative to the funds and long-term planning needed to maintain engineered assets of this kind.

RP funding mechanisms face shortfalls relative to asset requirements for maintenance and repairs that limit the custodian's ability to implement long-term solutions to maintain assets in optimal conditions on an ongoing basis

As mentioned in section 2.8 RP's actual expenditures have increased from $117M to $195M during the scope of the evaluation. However, most of this funding envelope represents Vote 1 funds for day-to-day operating costs as opposed to Vote 5 funds for capital spending which is what includes the recapitalization of jetties and wharves at the end of their useful life.

Due to their complex engineered nature, jetties and wharves require long term planning and large-scale capital investments. For instance, the average cost for all wharf repair and recapitalization is estimated at $20k to $70.5M, based on average internal estimates of their cost replacement value. However, RP's capital budget is insufficient relative to the cost of maintenance for these complex engineered assets and leads to planning challenges. RP has identified the following significant funding shortfalls in 2022-23:

- $3.8M funding shortfall for critical and compliance maintenance projects which risk RP's ability to provide Level II service; and

- $26.3M funding shortfall for all other repair and maintenance projects which have not received funding and can be expected to become critical and compliance requirements over time.

Furthermore, Vote 5 funds are allocated through a national budgeting and prioritization process that is based on a Functional Area model rather than specific asset categories. Under the Functional Area model, category 1, 2, or 6 sites containing jetties and wharves may or may not be included in priority sites that are maintained at a Level ll service standard (i.e., receiving regularly scheduled maintenance subject to available funding).

Description

The figure depicts how Real Property's expenditures, including Vote 1 and Vote 5 funds, have increased between fiscal year 2016-17 and 2020-21. In fiscal year 2016-17, total Real Property expenditures consisted of $48M in Vote 5 funding and $67M in Vote 1 funding. In fiscal year 2017-18, total Real Property expenditures consisted of $53M in Vote 5 funding and $109M in Vote 1 funding. In fiscal year 2018-19, total Real Property expenditures consisted of $71M in Vote 5 funding and $108M in Vote 1 funding. In fiscal year 2019-20, total Real Property expenditures consisted of $75M in Vote 5 funding and $110M in Vote 1 funding. In fiscal year 2020-21, total Real Property expenditures consisted of $77M in Vote 5 funding and $109M in Vote 1 funding.

Across the 5 years, most, or 61%, of Real Property total expenditures came from Vote 1 authorities while Vote 5 funds accounted for 39% of the total.

CCG interviewees noted the need to prioritize funds by asset categories (as opposed to functional area) given the competition that can take place across asset categories within regions.

3.4.3 Funding challenges

Funding mechanisms result in lifecycle management challenges due to changing regulatory requirements, increased maintenance expenses, and procurement. Funding mechanisms are not considered to be sustainable in the future. Alternative funding mechanisms are presented.

Funding mechanisms create planning challenges for SCH and RP custodians that affect service delivery in the present day and are expected to continue affecting service delivery into the future

Small craft harbours, jetties and wharves are complex engineered assets that require stable funding and long-term planning to meet lifecycle and risk management requirements. Planning challenges due to short or insufficient funding cycles were cited as hindering factors for several reasons:

- Regulatory requirements are changing: Regulatory processes related to permitting, environmental assessments, and stakeholder and indigenous consultations have increased in complexity and are misaligned with funding timelines. Current funding mechanisms do not accommodate planning time for increasingly complex projects and timelines.

- Maintenance expenses are increasing: The maintenance, repair, and disposal of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves is costly. The incidence of storms, fires, and COVID-19 have caused the prices of material and labor to rise whereas budgets have not increased proportionally to accommodate increasing operating costs. Operation and maintenance reference levels for RP are not price protected therefore RP's purchasing power has also significantly decreased due to inflation.

- Procurement is challenging: To complete projects within short timeframes, the SCH program hires large contractors whereas using smaller contractors for longer periods of time would reduce tendering costs. RP financial delegations for construction have been updated but remain less than what the SCH program has at their disposal.

Alternative funding models were considered beneficial for the management of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves. Options included accrual budgeting and increasing A-base funding envelopes. Alternative funding models are further discussed in Annex D. Without the ability to plan for the long-term maintenance of assets, custodians are only able to invest in surface level solutions and stop gap measures, as needed. Given the present funding challenges, SCH and RP survey respondents considered their respective funding mechanisms to be somewhat appropriate to ensure service delivery in the present day and somewhat less appropriate to ensure service delivery in the future.

Some SCH respondents (44%) rated the appropriateness of custodial funding mechanisms between a moderate and great extent in the present day, versus a few (22%) who rated their appropriateness likewise in the future.

Few RP respondents (23%) rated the appropriateness of custodial funding mechanisms between a moderate and great extent in the present day, versus a few (17%) who rated their appropriateness likewise in the future.

3.4.4 SCH and RP governance mechanisms

In general, both SCH and RP governance structures are appropriate to support the management of DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves.

SCH program and HA governance structures are appropriate to support service delivery

A majority of SCH and HA survey respondents indicated that governance structures are appropriate to a moderate and great extent. Within the department, SCH's national headquarters ensures consistency in the application of policies, while remaining mindful of the varying needs and circumstances of regions. Management oversight by the National SCH Managers' Committee (NMC)Footnote 3 includes all aspects of program operations, including RP management of small craft harbour infrastructure as well as SCH client services to HAs. Additional findings related to HA management can be found in Annex E.

A majority of SCH respondents (78%) indicated that SCH governance structures are appropriate to a moderate (28%) and a great extent (50%).

A majority of HA respondents (85%) indicated the HA governance mechanism is appropriate to a moderate (21%) and great extent (64%).

RP governance structures are generally appropriate to support service delivery

Most RP respondents indicated that governance structures are appropriate to a moderate and great extent. RP's National and Regional Centers of Expertise are intended to centrally focus custodial knowledge of national policies, planning and direction while ensuring responsiveness and flexibility in local services to support departmental users.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, CCG interviewees indicated that RP's governance structure can hinder CCG operations and that collaboration between CCG and RP could be increased with regards to the planning, activities, structures, and processes that support service delivery. Communication and collaboration are further discussed in section 3.4.10.

Most RP respondents (67%) indicated that RP governance structures are appropriate to a moderate (11%) and a great extent (56%).

A majority of CCG interviewees (88%) indicated there could be increased collaboration between CCG and RP to a moderate(25%) and a great (63%) extent.

3.4.5 Information management for DFO's small craft harbours

The availability of operational data that is relevant to small craft harbours can be improved to support decision making.

SCH's information management capacity could be strengthened to meet evolving program needs for information to support decision-making

The SCH program relies on data on the state of their core and non-core harbours. Data is gathered by technical and engineering SCH staff via regular asset inspections and condition assessments that take place every 3 years.

Interviewees indicated the following challenges affect the program's capacity in information management:

- Historical data cannot be easily accessed to support decision-making – Data is recorded in the SCH Management Information Repository (SCHMIR), which houses national information from several depositories and only displays data available as of the date it is accessed. SCH staff are currently manually updating the number of harbours in the SCHMIR database.

- Accurate program data is not readily available – Interviewees noted that program data related to maintenance or inspection information is difficult to locate and national consistency is needed when feeding information into SCHMIR.

- Responding to increasingly frequent requests is a challenge – Staff noted that external requests, such as regulatory, ministerial and ATIP requests, are increasing and there is a need to strengthen the programs information management capacity, for instance, by creating a dedicated position for data management and GIS work.

To support future decision-making, additional information will be needed with respect to HA performance (strengths and vulnerabilities), understanding how harbours are performing, socio-economic trends and their impacts on harbours; and sites that are candidates for divestiture and associated barriers. As part of the SCH's long-term strategy, the program has begun conducting a large data gathering exercise across 1000 harbours including information related to:

- harbour capacity;

- state of the infrastructure;

- HA activity, use, and health including management, governance, and financial health;

- changing environments, including socio-economic and fisheries needs; and

- the feasibility of divestiture.

3.4.6 Information management for DFO's jetties and wharves

RP operational data is not available by jetties and wharves asset groups due to internal challenges assessing marine engineered assets.

There is a gap in jetty and wharf specific information available to support decision making

To support the various portfolio analysis and reporting processes, RP relies on up-to-date information on the individual systems, replacement costs, deferred maintenance, and physical condition of the assets in the national portfolio. However, jetty and wharf specific data is not available because it is not collected by RP for multiple reasons:

- Condition assessment data is collected by functional area/site – RP uses average site condition indexes which take in account the condition of assets at each site but do not include detailed asset-specific information.

- Marine infrastructure assessment expertise is lacking – Condition assessments are carried out by third party engineers who specialize in capturing standard building assets (i.e., office buildings) and often do not have the expertise to provide in-depth assessments of specialized marine infrastructure components, such as underwater components. There is a need for expertise by groups that specialize in this type of infrastructure analysis.

- Methodologies for assessing marine infrastructure are under development – The overall condition indexes for the components of a site are determined using non-intrusive visual assessments. However, visual assessments are insufficient to quantify components that are buried or underwater for marine engineered infrastructure and may lead to misleading conclusions.

- Specialized assessments for marine engineered infrastructure are costly – The cost of intrusive assessments that can be carried out underwater is significant and impacts their feasibility, timing and frequency. Therefore, RP is limited in conducting these assessments in support of recapitalization work.

In 2019, Fleet and Maritime Services gathered wharf information relevant to CCG operations and produced a Wharf Inspection Report which included wharf importance to CCG operations (for all sites), wharf condition (as available for some sites (40%) but not standardized), estimated replacement values (for some sites (33%), future status of wharves (for a few sites (25%), and remaining useful life (for a few sites (15%).

The Maritimes and Civil Infrastructure (MCI) branch of ITS is also conducting shore-infrastructure assessments to support fleet modularity. Assessments will provide information on the current condition of DFO's wharves, existing features that can support modularity, and potential modifications to support the CCG strategy. Though the assessment is guided by MCI, all engineering and technical work is to be carried out RP, including engineering and technical contracts carried out internally or by Public Services and Procurement Canada.

3.4.7 Performance measurement for DFO's small craft harbours

Performance data for the SCH program indicates that performance targets are being met. However, there is a need for program results and indicators that can tell an accurate performance story with regards to the SCH asset portfolio in the long-term.

SCH program results are mostly linked to specific funding commitments, leading to gaps in the program's performance measurement strategy

The evaluation found that SCH results and performance indicators are mostly associated to commitments from periodic infusions of temporary funding. As a result, performance targets are representative of actions taken in the short-term which boosts the program's results story through the appearance of results being consistently achieved. However, program data indicates that the overall SCH portfolio continues to deteriorate as assets age over the course of their lifecycle. The program could benefit from developing indicators and targets geared towards the achievement of long-term outcomes that would allow for a more representative and transparent results story of SCH program effectiveness.

SCH performance measurement could be strengthened through improvements to performance indicators

Interviewees identified the need for indicators that can speak to the usefulness, health and evolution of small craft harbours as this is tied to harbours' role as economic drivers and ports of refuge in remote locations rather than the strict value of catch landings. Program indicators that are reflective of evolving needs (i.e., related to reconciliation, recreational use and climate resilience) would help support decision-making. HA satisfaction could also be monitored via indicators related to the health of HAs.

The SCH program is achieving results linked to short-term funding commitments tracked through program information profiles.Footnote 5,Footnote 6 For instance:

- the result that the commercial fishing industry has access to safe harbours has been completed. A new target is implemented year over year;

- the result that safe harbours are maintained has also been completed. Result was projected to be achieved by March 2021; and

- the result that harbours are ready for divestiture was also completed. Result was projected to be achieved by March 2021.

Half of SCH respondents (50%) indicated that performance data is appropriate to a moderate (28%) and great extent (22%).

3.4.8 Performance measurement of DFO's jetties and wharves

Performance data related to jetties and wharves is not collected by the department.

Performance data that is specific to jetties and wharves is not tracked by the department

RP performance information is tracked in an Internal Service Performance Information Profile alongside 12 other internal services, such as communications, legal services and security. As an internal service, RP's performance information does not link to any departmental results, rather a long-term outcome that “crown owned buildings are cost-effectively maintained in a sustainable, compliant manner throughout their lifecycle to support program delivery and government priorities with a high performing real property organization.”

In achieving this target, RP employs an outcomes-based logic model that lays out portfolio-level activities and outcomes, therefore performance data for indicators at the individual asset-level, such as jetties and wharves, are not collected by the department. RP interviewees mentioned a need for indicators that better reflect the usefulness of assets, such as use and occupancy, as this information is not currently tracked.

RP and SCH custodians indicated that improvements could be made to centralized databases, data-management systems, and performance indicators:

- some RP (40%) and SCH (28%) custodians indicated improvements can be made to data-management systems;

- some RP (40%) and SCH (36%) custodians indicated improvements can be made to centralized data-bases; and

- few RP (20%) and some SCH (32%) custodians indicated improvements can be made to performance indicators.

CCG interviewees noted that it would be helpful to develop indicators that quantify impacts on departmental users, as there are no current mechanisms to track this information. Examples include days impacted from lack of wharf access and costs associated with wharf disrepair.

3.4.9 Asset management: prioritization of DFO's small craft harbours

There are pressures on the SCH program that affect its ability to plan and prioritize projects for lifecycle management.

The SCH program prioritizes the safety of its harbours

Priority investment projects are assessed through a National Peer Review to determine which projects represent the best value for money and outcomes for the program. Interviewees have noted that, due to the lack of stable funding, the program operates reactively by ensuring there are “shelf-ready” projects ready to go for when new funding is announced. SCH planning optimizes the program's limited budget by prioritizing projects related to safety repairs (including dredging), upgrades required for harbour safety or improving operations at core fishing harbours, and small urgent safety related repairs or mitigation measures (e.g., barricades) at non-core harbours pending their divestiture.

Barriers to ensuring current and future service delivery include:

- Harbour Authority continuity planning: The administration of SCH is overseen by a national network of volunteers, or the equivalent of 70 Full Time Equivalents (FTE) dedicated to harbour operations. Since DFO lacks the resources needed to maintain this network of harbours, ensuring the long-term continuity of HA's is critical for the program. However, planning for the continuity of HA's is challenging due to small and/or aging population groups. SCH faces recruiting challenges due to changing demographics as previous cohorts enter retirement and a general lack of interest from new cohorts. HA volunteers reported high levels of stress in carrying out duties due to the high expectations, lack of paid positions lack of enforcement authority to oversee operational management. Incentives such as providing funds to hire employees and granting tax credits to volunteers were suggested.

- SCH staff retention: A recent staff reclassification exercise has led to challenges in staff retention among SCH's client service employer groups. These positions tend to be relationship-based, therefore the lack of staff resources, knowledge, and training has resulted in a misalignment between levels of experience and work requirements. As a result, SCH's ability to build internal experience, retain corporate knowledge, and maintain a regular client interface with HA's is challenged. HA's echoed this challenge in establishing relationships, noting that constant staff turnoveads to difficulty maintaining open lines of communication and conducting site-visits.

3.4.10 Asset management: Prioritization of DFO's jetties and wharves

Strategic and operational communication challenges exist between RP and departmental user groups that could be addressed to improve the prioritization process for jetties and wharves.

The prioritization of jetty and wharf projects is limited by RP's need to conduct lifecycle management of a national portfolio

RP's ability to proactively prioritize and plan for jetties and wharves requires prior knowledge of user's evolving operational requirements, (including ancillary ship infrastructure) as well as clients' strategic direction and vision. RP's current national portfolio approach may or may not result in functional areas that include jetties and wharves receiving funding as part of broader site asks for repair and maintenance, utilities, security and other expenses. While the physical condition of assets is considered as component of a site, RP typically prioritizes components that require recapitalization.

RP is strengthening its lifecycle management approach by adopting an Asset Prioritization Model which will consider the lifecycle of all individual assets in the national portfolio over a 20-year horizon. This will enable RP to objectively consider when to recapitalize assets (i.e., when the end of useful life has been reached) or carry out asset disposal (i.e., when operation and maintenance costs are too high). Under this model, assets on Priority sites will be the focus based on their importance to CCG and DFO operations.

There are opportunities to improve collaboration and communication with departmental user groups during planning and prioritization processes.

DFO and CCG users indicated a need for coordinated and consistent departmental communication to improve jetty and wharf service delivery given the department-wide impacts that assets can have on user operations. For instance, this could include:

- Increasing departmental consultation to understand users' evolving infrastructure needs;

- Defining RP roles and responsibilities across sites as these can vary and lead to the operational isolation of certain sites; and

- Seeking opportunities to collaborate with other federal departments who manage marine infrastructure;

Although further action could be taken to strengthen communication and collaboration practices, particularly at the regional level, many steps have already been taken. For instance:

- RP and CCG staff participate in national joint committees, working groups, and special initiatives.

- The CCG has created a dedicated RP liaison position to better represent CCG interests in certain regions.

- The CCG Is developing national strategies to communicate infrastructure requirements, for instance through the 2019 National Wharf Strategy.

Continuing collaboration between RP and departmental users will continue to be beneficial for the departmental management of DFO's jetties and wharves.

On average, CCG interviewees indicated their perspectives as departmental users were reflected in planning activities, structures, and processes between a small to some extent.

3.4.11 Asset management: Planning considerations for DFO's small craft harbours, jetties and wharves

Overall, there is evidence that SCH and RP custodians incorporate environmental considerations in the planning, activities, structures, and processes that support service delivery. There are opportunities to increase awareness of how GBA+ principles apply to custodial functions.

Custodial groups implement environmental considerations during lifecycle management processes

While environmental considerations (i.e., water, habitat protection, contamination) are federally regulated, custodians identified that their funding and long-term planning capacities limit their ability to address increasingly complex environmental regulations. For example, environmental requirements related to dredging activities are becoming increasingly challenging as permits, environmental assessments, and approvals are required before dredging waste can be disposed. CCG and HA interviewees have identified a need for dredging to take place on a regional site-by-site basis therefore additional funding and longer project timeframes will be required to ensure that dredging activities have minimal impacts on the environment.

- Best Practice: RP interviewees indicated that staff are trained in impact assessments of climate change and have been engaging end-users and scientists to develop a climate resiliency score on all wharfs to ensure their long-term resiliency.

Most SCH (66%), HA (50%), and RP (55%) survey respondents indicated that efforts to include environmental considerations have been made from a moderate to great extent.

There are opportunities to increase awareness of how GBA+ can be applied to custodial functions

The evaluation found that the level of awareness in the degree to which GBA+ can be applied to departmental infrastructure was higher among senior management interviewees than respondents to a staff survey. Interviewees expressed that efforts have been made to consider the needs and perspectives of diverse populations in the planning, activities, structures and processes that support the service delivery of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves. However, staff indicated low awareness of how GBA+ principles can and should be applied to custodial functions. While some HA respondents to a staff survey (28%) indicated efforts have been made to consider the experiences of diverse groups of people at individual harbours from a moderate to a great extent, some (29%) equally indicated they had not at all been considered.

- Best Practice: There is evidence the SCH program considers GBA+, particularly when supporting and conducting consultations with Indigenous partners. For instance, clear consideration is given to capacity restraints faced by Indigenous Harbour Authorities and the need for capacity building and increased flexibility is recognized and addressed by the program.

Most SCH (61%) and a majority of RP (78%) survey respondents indicated that they either did not know how GBA+ considerations apply to the service delivery of small craft harbours, jetties and wharves, or that they were not applicable.

3.4.12 Asset Management: Divestiture of DFO's small craft harbours

SCH's divestiture program advances the removal of non-core harbours from the program inventory. However, more than half of non-core harbours slated for divestiture have yet to commence.

The SCH program divests its assets through an established divestiture program, yet divestitures are challenging to carry out

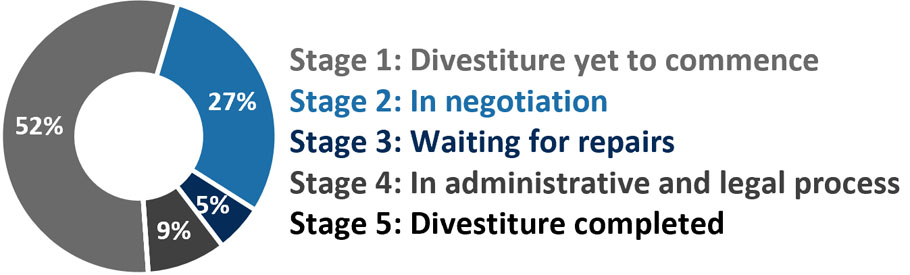

The SCH program aims to remove non-core harbours from the program inventory to reduce departmental liabilities and achieve cost savings for the program (Box D). There are 5 stages to the SCH divestiture process (Figure 14). SCH data indicates that more than half of non-core harbours are at Stage 1, followed by Stage 2.

Description

The figure depicts the 5 stages of the Small Craft Harbour program's divestiture process, as well as the proportion of assets at each stage. For instance, 52% of the small craft harbour program's assets are in stage 1: divestiture yet to commence; 27% are in stage 2: in negotiation; 5% are in stage 3: waiting for repairs; there are no assets in stage 4: in administration and legal process; and the remaining 9% are in stage 5: divestiture completed.

As of July 2018, 1,136 non-core harbours have been divested at a cost of roughly $123 million. Criteria used to select disposal or divestment projects at non-core harbours include project readiness, advancement of the negotiation process, degree of public expectations, and significance of safety or environmental concerns. Nevertheless, the divestiture of remaining non-core harbours is not attainable with the program's current divestiture budget and timelines due to their high cost and complexity; A-base funds available to the program are insufficient to carry out divestiture projects within a year while B-base funds are typically targeted at specific projects, limiting SCH's ability to prioritize projects.

Factors that present divestiture challenges for remaining non-core harbours include the existence of multiple, potentially overlapping, Indigenous treaties and land claims, such as in Peace River, Alberta; the lack of special authorities to accelerate divestiture; the dependence on external interest of parties to divest to; and high market value assessments of infrastructure.

Box D. Departmental importance of disposal and recapitalization

The disposal and recapitalization of assets at the end of their useful lifecycle is an important step for the department. Once facilities have reached the end of their useful life, they can be recapitalized, reconstructed or targeted for divestiture. DFO is no longer responsible for costs and liabilities associated with assets that have been divested. Therefore, when non-core or non-priority assets cannot or are not divested, they present departmental liabilities and risks including but not limited to:

- Risk to users – the deterioration of non-core/non-priority assets that cannot be divested poses a departmental liability if their condition progresses to unsafe conditions. If needed, the department takes action to barricade assets in poor condition, but this does not necessarily reduce liability as there have been instances of restricted access notices being ignored.

- Diverted resources – funds spent to maintain non-core/non-priority assets, or upgrade them levels prior to divestiture, represent funds that are diverted from core/priority assets. Core/priority assets support departmental mandates and need to be maintained and kept in safe conditions within funding limits. There is a risk that the lack of attention to core/priority assets directly impacts their condition and intended results of core programs and services.

- Environmental contamination – asset deterioration can lead to liabilities with respect to environmental contamination.

3.4.13 Asset management: Recapitalization of DFO's jetties and wharves

RP rarely divests and/or disposes of DFO's jetties and wharves due to their prohibitive cost.

RP divestiture budget are insufficient to support the activities' high cost related to jetties and wharves

RP's activities focus on ongoing capital projects rather than divestiture activities. Unlike SCH who have had a divestiture program and intermittent B-base funding made available to progress with divestiture, RP's national budget for divestiture is much lower and divided across a national portfolio. While there is a plan for divestiture in place, there is no process to prioritize what assets should be slated for divestiture; those that have no useful purpose become surplus, and the sector is more reactionary.

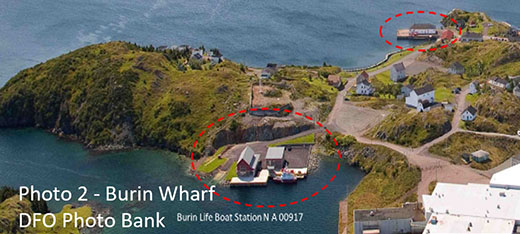

When possible, RP mainly divests of lighthouses and associated infrastructures under the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act (HLPA). The divestiture of jetties and wharves is rarely undertaken due to their prohibitive cost. For instance, of 96 assets in RP's 2022-23 Divestiture Plan, only one wharf located in the town of Burin was slated for divestiture and acquisition by a local municipality (Box E). For this project, the cost of the preferred option for divestiture was higher than the annual divestiture budget for the entire portfolio.

Box E. The divestiture of Burin wharf