Horizontal evaluation of funding dedicated to whales

Final Report

March 2023

Horizontal evaluation of funding dedicated to whales

(PDF, 2.52 MB)

Table of Contents

- 1.0 Evaluation context

- 2.0 Profile of whale-related initiatives

- 3.0 Evaluation findings

- 4.0 Conclusions and considerations

- 5.0 Appendices

- Footnotes

1.0 Evaluation context

The Horizontal Evaluation of Funding Dedicated to Whales was led by Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s (DFO) Evaluation Division in collaboration with three other federal partner departments and agencies (PDAs) that have responsibilities for the delivery of whale protection and recovery measures:

- Transport Canada (TC);

- Parks Canada (PC); and

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

The evaluation was conducted between May and November 2022. It complies with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and responds to a requirement to conduct an evaluation of Southern Resident killer whale measures by March 2023.

1.1 Objectives and scope

The objective of the evaluation was to provide senior management with evidence-based information to support decision-making. The scope of the evaluation was established through a planning phase, which included document review, file review, scoping discussions with program representatives from all four PDAs, and a consultation with DFO’s Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee.

The evaluation was designed to provide evidence on what worked well and where improvements could be made with respect to the protection and recovery of three endangered whale species: the North Atlantic right whale (NARW), the Southern Resident killer whale (SRKW), and the St. Lawrence Estuary beluga (SLEB). It included an assessment of design and delivery, progress on addressing threats, and lessons learned for future programming for the time period from 2017-18 to 2021-22.

The scope of the evaluation did not include an assessment of the specific programs or initiatives that have some responsibilities for whale-related programming [e.g., the Species at Risk Program (SARP), Canada’s Nature Legacy], although some whale-related activities undertaken as part of recovery strategy and action plans may be reflected in the report. In addition, the evaluation did not cover any Arctic regions because no whale protection and recovery activities have been funded to-date in those regions.

1.2 Methodology

Evaluation questions

The evaluation examined eight questions related to design and delivery, progress on addressing threats, and lessons learned for future programming.

Design and delivery

- To what extent were activities aligned with departmental programs, priorities, and mandates?

- To what extent were the activities:

- implemented as planned;

- appropriate to achieve intended results; and

- flexible to allow for course corrections as needed?

- What internal or external factors enabled or hindered PDAs’ abilities to achieve the intended results?

- To what extent was there Indigenous involvement in whale-related programming?

Progress on addressing threats

- To what extent was progress made to address threats [i.e., disturbance (acoustic and physical), vessel strikes, entanglements, prey availability and quality, and contaminants] to the targeted species?

- To what extent have activities contributed to progress in achieving desired outcomes as defined by Indigenous communities and groups (if applicable)?

Lessons learned for future programming

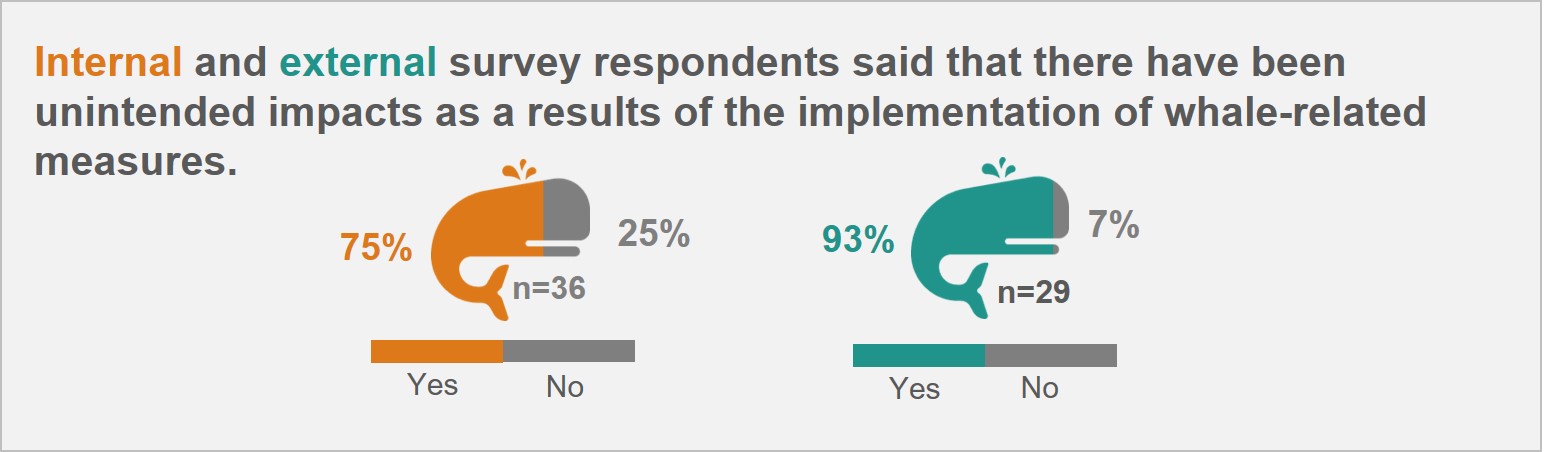

- Were there any unintended impacts, either positive or negative, as a result of whale-related programming?

- How can the effectiveness and/or efficiency of participating departments and agencies be improved going forward in terms of whale-related programming?

Data collection methods

The evaluation used multiple lines of evidence including, document review, interviews, internal and external surveysFootnote 1, administrative data review, case study on Indigenous involvementFootnote 2 and an environmental scan. For full details on the evaluation methodology, including limitations, see Appendix A. Four specifically selected activities were examined in-depth to understand the achievement of results and lessons learned: voluntary slowdown measures, marine mammal response providers, whale-related aerial surveillance and whalesafe fishing gear/technologies (see Appendix C for more detail).

2.0 Profile of whale-related initiatives

2.1 Overview of funded initiatives

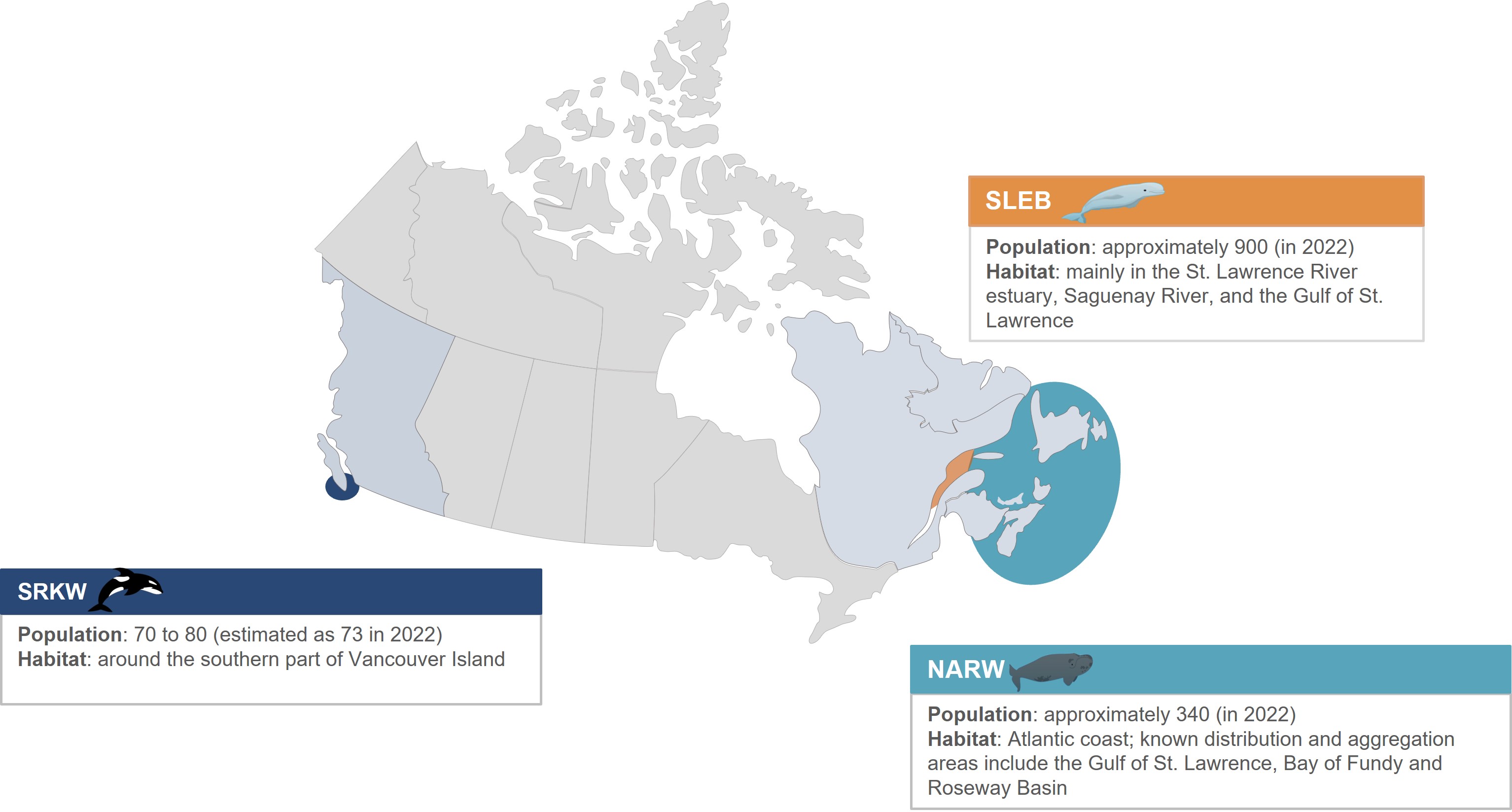

Starting in 2017, the Government of Canada made investments to help protect and support the recovery of three endangered whale species: the NARW, the SRKW, and the SLEB. For more information on these species, see Figure 1 below.

Long description

This figure depicts a map of Canada that highlights the habitats and estimated populations of the three targeted whale species. There was an estimated 70 to 80 SRKW living around the southern part of Vancouver Island in 2022. That same year, there were approximately 900 SLEB living mainly in the St. Lawrence River estuary, Saguenay River, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Lastly, there were approximately 340 NARW living in areas of the Atlantic Ocean, including the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Bay of Fundy, and Roseway Basin in 2022. This data was sourced from the DFO website, recovery strategies and other reports.

These investments were made through four key initiatives and projects delivered by DFO/the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), TC, ECCC, and PC.

- Oceans Protection Plan (OPP) was funded between 2017-18 and 2021-22. Two sub-initiatives, Marine Environmental Quality and Whale Detection and Avoidance, focused on understanding the impact of shipping-related noise on the SRKW, NARW, and SLEB and on testing whale detection technologies to reduce the risk of vessel strikes.This initiative was delivered by DFO and TC.

- Whales Initiative was funded between 2018-19 and 2022-23 to address human-induced threats for SRKW, NARW, and SLEB in support of the implementation of Species at Risk Act recovery strategies and action plans for these species. This initiative was delivered by DFO, ECCC, and TC.

- SRKW Initiative was funded between 2019-20 and 2022/23 to extend the Whales Initiative for the SRKW species, building on the reporting structure already in place while addressing threats to SRKW on a broader and faster scale. This initiative was delivered by DFO, ECCC, TC, and PC.

- Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) was funded between 2019-20 and 2021-22. Recommendations 5 and 6 were made to monitor, assess, and report, over time, on the extent to which the increase in Project-related underwater noise has been offset by the underwater noise measures and informed adaptive management of measures. This initiative was delivered by DFO/CCG and TC.

2.2 Spending on key whale-related programming

Table 1 provides an overview of the spending for the four whale-related initiatives/projects, which totaled $227.1 million between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

| Initiative | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPP – selected initiativesa | $9.6 | $13.6 | $11.6 | $ 8.2 | $7.5 |

| Whales Initiative | - | $25.6 | $40.7 | $37.1 | $32.9 |

| SRKW Initiative | - | - | $7.0 | $13.2 | $11.3 |

| TMX Recommendations 5/6 | - | - | $3.9 | $ 2.7 | $2.2 |

| Total | $9.6 | $39.2 | $63.2 | $61.2 | $53.9 |

| Source: Departmental Results Reports (DRR) Horizontal Initiatives Supplementary information tables and internal financial information from each PDA. | |||||

a. OPP also provided $4.5M in grants and contributions over four years (originally part of the Coastal Restoration Fund) for increasing capacity for safe and effective incident response, which is included in these OPP figures.

Long description - Table 1

Spending for the four whale-related initiatives/projects totaled $227.1 million between 2017-18 and 2021-22. Across all initiatives/projects, a total of $9.6 million was spent in 2017-18, $39.2 million in 2018-19, $63.2 in 2019-20, $61.2 in 2020-21, and $53.9 million in 2021-22.

Selected initiativesa in OPP spent $9.6 million in 2017-18, $13.6 million in 2018-19, $11.6 million in 2019-20, $8.2 million in 2020-21, and $7.5 million in 2021-22.

The Whales Initiative spent $25.6 million in 2018-19, $40.7 million in 2019-20, $37.1 million in 2020-21, and $32.9 million in 2021-22.

The SRKW Initiative spent $7.0 million in 2019-20, $2.7 million in 2020-21, and $11.3 million in 2021-22.

Lastly, for TMX recommendations 5/6, $3.9 million was spent in 2017-18, $2.7 million in 2019-20, and $2.2 million in 2021-22.

Other ongoing programing and initiatives, not included in this spending (e.g., SARP, Canada’s Nature Legacy, and Enhanced Nature Legacy), also supported activities for the protection and recovery of marine mammals, including whales (e.g., Whalesafe Gear Adoption Fund and Ghost Gear Fund).

2.3 Overview of funded activities and PDA responsibilities

As part of the investments, PDAs were responsible for a number of activities. These activities were funded to help mitigate threats that affect the survival and recovery of the endangered whale species: disturbance (acoustic and physicalFootnote 3), vessel strikes, and entanglements; prey availability and quality; and contaminants. Below is a high-level summary of the key funded activities for each of the PDAs and the threats they are intended to address.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Lead) / Canadian Coast Guard

- Implement fishery management measures such as changes to open/close dates, closure protocols and gear modifications for the prevention of entanglements, for minimizing physical and acoustic disturbance, and to support availability of prey, such as Chinook salmon.

- Deliver the Marine Mammal Response Program (e.g., disentanglements).

- Conduct compliance and enforcement activities (e.g., to monitor fishing activities and gear use, whale approach distances).

- Collect vessel traffic information for TC.

- Conduct public education/outreach.

- Conduct scientific research and monitoring on whale movements, habitat, behaviour, threats, and other aspects.

The activities undertaken by DFO and CCG were intended to address the threats of disturbance (acoustic and physical), vessel strikes and entanglements; prey availability and quality; and contaminants.

Transport Canada

- Manage vessel traffic (e.g., create vessel slowdown zones, vessel restricted areas, and manage shipping lanes).

- Conduct enforcement activities (e.g., issue interim orders and related compliance). Sometimes these are carried out by DFO fishery officers or PC park wardens on TC's behalf.

- Conduct surveillance on whale presence, including surveillance supported by DFO Conservation and Protection and Science.

- Conduct research activities on reducing underwater vessel noise and physical and acoustic disturbance of ships to marine mammals in busy shipping areas.

- Conduct public education and outreach and partner with various stakeholders in Canada and Internationally.

The activities undertaken by TC were intended to address the threats of disturbance (acoustic and physical), vessel strikes, and entanglements.

Parks Canada

- Protect and preserve national parks and marine conservation areas.

- Conduct research and monitoring offsite and within national parks reserves.

- Conduct outreach, education, engagement, and promotion with Indigenous communities and groups, and other stakeholders.

- Carry out compliance and enforcement activities within the national park reserves and within interim sanctuary zones under TC’s jurisdiction.

The activities undertaken by PC were intended to address the threats of disturbance (acoustic and physical), vessel strikes, and entanglements; prey availability and quality; and contaminants.

Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Research, monitor, and assess contaminants that are harmful to whales, their prey, and their habitat.

- Prevent pollution and regulate and mitigate the release of contaminants.

- Conduct enforcement activities (i.e., inspections and investigations) and issue enforcement measures to prevent the release of harmful contaminants and hold polluters to account.

The activities undertaken by ECCC were intended to address the threats of contaminants.

3.0 Evaluation findings

3.1 Design and Delivery

3.1.1 Legislative and regulatory tools for whale protection and recovery

PDAs have the regulatory tools to effectively carry out their roles. Progress has been made on funded initiatives related to legislative and regulatory tools; however, some gaps and challenges remain.

Enabling legislation, regulations, and agreements

PDAs are governed by several pieces of legislation and associated regulations, which provide the authority to implement various actions that directly or indirectly benefit endangered whale species. These include the:

- Fisheries Act;

- Oceans Act;

- Species at Risk Act;

- Canada National Parks Act;

- Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park Act;

- Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act;

- Canada Wildlife Act;

- Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999; and

- Canada Shipping Act (CSA), 2001.

Regulations stemming from these acts, such as the Marine Mammal Regulations (MMR) and the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, also include important prohibitions and provisions (see Appendix D for more information on the acts).

Several of the acts include provisions for the protection of specific marine areas for the purposes of conservation. These areas include ecologically significant areas, marine protected areas, national marine conservation areas, critical habitat, and marine national wildlife areas. There are also a number of emergency measures within the acts that can be implemented where immediate action is required for the protection of whales (see box 1).

Box 1: Emergency measures available for the protection of endangered whales

Fisheries Act: fisheries management orders for promptly addressing threats to the proper management and control of fisheries and the conservation and protection of fish. Orders can prohibit or limit fishing, the use of certain gear, or impose any other requirements.

Oceans Act: establishment of interim marine protected areas on an emergency basis, if a marine resource or habitat is likely to be at risk.

Species at Risk Act: emergency orders to protect species facing imminent threats to their survival or recovery; may identify critical habitat and include prohibitions or required actions to protect the species and its habitat.

Canadian Wildlife Act: allows the Minister to take measures as deemed necessary for the protection of wildlife in danger of extinction.

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999: interim orders for immediate action to protect the environment or human health in cases where a substance is or could be toxic, and it is either not on the List of Toxic Substances, or it is on the list and it is not adequately regulated.

CSA, 2001: interim orders, as a temporary regulatory tool, if immediate action is required to deal with a direct or indirect risk to marine safety or the environment.

In addition, there are international agreements and laws that Canada is subject to, which also include relevant authorities and obligations. These include the Convention on Biological Diversity (1996)Footnote 4, the Accord for the Protection of Species at RiskFootnote 5, and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.Footnote 6

Sufficiency of legislation, regulations, and agreements

The acts and regulations provide the necessary legislative framework for the protection and recovery of endangered whale species. The provisions therein address the various identified threats to whales, and interviewees and survey respondents felt that regulatory tools and authorities to support the implementation and enforcement of whale-related measures were in place and overall effective.

Long description

A visual depicts two whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 56 internal survey respondents, 45% believed that the necessary regulatory tools are in place to a great extent, 53% to some extent and 3% to no extent. Furthermore, of 50 internal respondents, 20% believed that the tools are effective to a great extent, 66% to some extent and 14% to no extent.

Progress has been made with respect to the implementation of funded activities related to legislative and regulatory tools.

- The MMRs were amended in 2018 to apply to conservation and protection of marine mammals, by providing new minimum approach distances, implementing mandatory reporting of interactions, and clarifying the definition of disturbances.

- Amendments to the CSA, 2001 were completed in 2018, allowing the government to regulate for environmental reasons and giving the Minister of TC the power to make interim orders if immediate action is required to deal with threats to marine safety or the marine environment.

- Proposed amendments to the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations to add or further restrict seven contaminants harmful to whales have been published for comment.

Challenges and gaps

Some legislative and regulatory gaps and challenges were identified.

- There are currently no comprehensive regulations in place to regulate the activities of whale watching vessels, aside from the minimum approach distances and sustainable whale watching agreement and licensing scheme (both concerning SRKW specifically), which are included in SRKW-related annual interim orders made by the Minister of Transport under the CSA, 2001. It is challenging to produce sufficient evidence on the violation of approach distances.

- Interim orders under the CSA, 2001 are considered a very effective mechanism; however, they are a temporary short-term solution with some limitations regarding prevention and sustainability. Other tools, like marine protected areas, take a long time to implement, so there is a gap in the medium-term. Several interviewees expressed that a permanent regulatory process is needed.

- Enforcement relies heavily on automatic identification system (AIS) transponder data to provide information on ship identity, speed, and direction. However, many vessels are not required by regulation to carry AIS transponders (e.g., small vessels less than 13 m of length), thus making enforcement more difficult.

- There are regulations that challenge the ability to implement closures of fishing areas using variation orders (e.g., Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licenses Regulations). Furthermore, some current regulations related to fisheries for other species may impede progress on some measures such as rope-on-demand fishing gear.

- Certain tools and regulations (e.g., interim sanctuary zones) are under TC jurisdiction. PC and DFO personnel can only provide warnings, document non-compliance, and report the violations to TC. This creates challenges and requires significant effort and coordination when it comes to staff enforcing other departments’ regulations.Footnote 7 Compliance with guidelines developed to address contaminants threats is voluntary, unless they become regulations. Implementing a regulation, however, is a multi-step process and typically takes several years. Furthermore, often it is difficult to identify the source of contamination and assign fault for contaminant issues.

3.1.2 Alignment with mandates, priorities and international practices

Funded activities to support the protection and recovery of the targeted species were well-aligned with the programs, priorities, and mandates of PDAs; and with international guidelines and practices of other jurisdictions.

Alignment with programs, priorities, and mandates

Many of the relevant pieces of legislation governing the PDAs explicitly include responsibilities that directly relate to the whale-related initiatives.

- The Canada National Parks Act states that the Minister’s first priority in the management of parks must be the maintenance or restoration of ecological integrity. The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park Act provides authority to make regulations for the protection of ecosystems, and any elements of ecosystems, in the park.

- The Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act holds the Minister responsible for marine conservation areas, including long-term ecological vision and ecosystem protection.

- The Species at Risk Act exists to prevent wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct; to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity; and to manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened. The Act states that the responsibility for the conservation of wildlife in Canada is shared among the governments in this country.

- The Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 states that the Minister has an obligation to administer the act in a manner that protects the environment.

- The Fisheries Act holds the Minister responsible for enforcing pollution prevention provisions, which prohibit the deposit of deleterious substances into water frequented by fish (definition of fish includes whales).

- The CSA, 2001 states that the Minister has the responsibility to protect the marine environment from damage due to navigation and shipping activities.

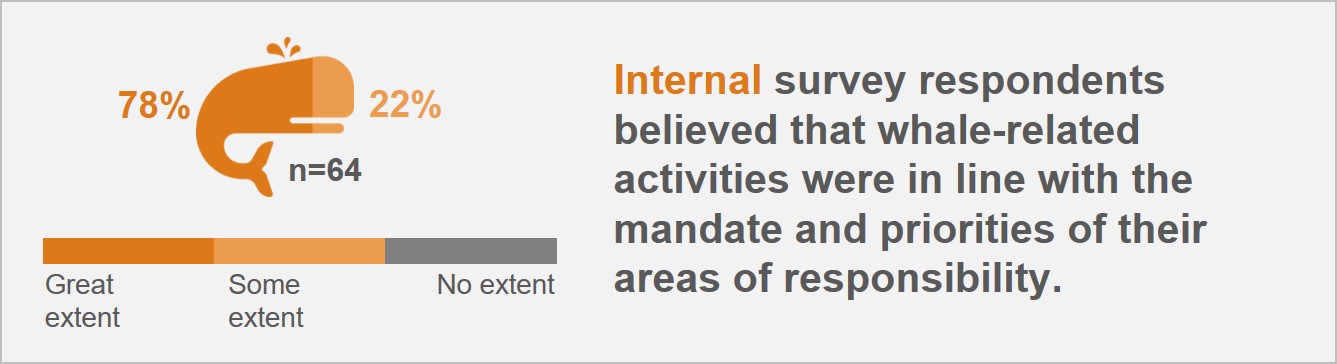

Long description

A visual depicts a whale shaped infographic that indicates that, of 64 internal survey respondents, 78% believed that the activities were in line with the mandate and priorities to a great extent and 22% believed they were aligned to some extent.

Additionally, the government’s priority-setting documents have made it clear that conservation generally, and that of whales specifically, is to be a priority. This is most clearly stated in the Budget 2018 announcement associated with the funding of the Whales Initiative, but the 2021 and 2022 budgetsFootnote 8 also included relevant funding announcements. Furthermore, recent mandate letters for DFO, TC, and ECCC included directives to reduce emissions in the marine sector, protect marine species and ecosystems, strengthen marine research and science, and conserve marine areas.

Finally, among the government's key priorities is reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. The government has increased efforts in this area over the past several years, recognizing its constitutional and treaty obligations and, in 2021, passing into law an Act respecting the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Recent departmental mandate letters included direction to build on the progress made with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people and on reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. Recognizing the significance of the three targeted whale species to Indigenous Peoples, the whale-related initiatives included funding for building partnerships with, and developing capacity within, Indigenous communities and groups to respond to marine mammals in distress.

Alignment with international practices

International bodies (e.g., International Whaling Commission, Food and Agriculture Organization) do not have recognized standards or practices related to the threats addressed by whale-related initiatives. Rather, they have published general guidelines on a variety of whale protection and recovery issues, including: large whale entanglement response, prevention and reduction of marine mammal bycatch, and whale watching.

Long description

A visual depicts a whale shaped infographic that indicates that, of 43 external survey respondents, 39% believed that funded activities are aligned with international guidelines to a great extent, 56% to some extent and 5% to no extent.

External survey respondents indicated that Canada is a leader in many practices related to whale protection and recovery, including for acoustic monitoring, particularly ship source underwater noise through the Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) program (see section 3.2.6). Canada is also contributing to the development of International Maritime Organization guidelines for the reduction of underwater noise from commercial shipping to address adverse impacts on marine life, and continues to be a leader in large whale disentanglement and the continued implementation of dynamic fisheries closures to mitigate key threats to whale recovery. A few examples were identified where Canada is aligned with practices in other jurisdictions.

- Canada’s actions to monitor and reduce contaminants [e.g., the Pollutants Affecting Whales and their Prey Inventory Tool (PAWPIT), SRKW Action Plan Recovery Measures] are aligned with similar practices and goals in the United States. Of note, the protocol that is currently being developed for the derivation of environmental quality guidelines for the protection of apex marine mammals is the first internationally.

- Canada has a partnership with the United States under Be Whale WiseFootnote 9 for aligned measures and communications actions on the Pacific coast. Both countries operate a regional response network composed of government, conservation organization, and Indigenous partners that ensure experts support safe and effective responses.

- Canada’s methods to protect NARW, including mandatory speed reductions, fisheries closures, and whalesafe fishing gear, are aligned with similar practices in the United States.

However, external stakeholders noted other international practices could help inform future whale-related programming in Canada.

- Whale watching licensing and regulations for SRKW in Washington State and the voluntary whale watching recognition program WhaleSENSE.

- Prey availability management measures in the United States, including hatchery fish mass marking, increased hatchery production, and removal of pinnipeds (i.e., a carnivorous aquatic mammal such as a seal or walrus).

- Development of anthropogenic noise (i.e., created by human activity) thresholds by the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive.

Box 2: Other notable practices in other jurisdictions

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has created a “gear library”, where it houses dozens of on-demand systems from different manufacturers. Fishers and researchers can borrow gear to test it, and in return, provide insights on how the gear works, problems encountered, and suggestions for improvement.

- To address ship strikes, the United States uses a number of practices, including Blue Whales Blue Skies voluntary speed reduction and Whale Alert.Footnote 10

3.1.3 Governance for whale-related initiatives

Some aspects related to the governance of whale-related activities were seen as successful, although some opportunities for improvement were identified.

Interdepartmental governance for whale-related initiatives

While governance was not a key focus, the evaluation examined interdepartmental governanceFootnote 11 using a forward-looking approach to identify lessons learned for the future.

The implementation of whale-related activities is guided by the Interdepartmental Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) Whales Committee, which includes ADMs from all four PDAs, as well as representation from other relevant departments, as necessary. The committee’s role includes maintaining oversight, providing strategic direction, and facilitating coordination amongst departments and alignment with other federal priorities, such as reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and energy development. It reports to and takes guidance from the OPP Deputy Ministers’ Committee to ensure whole-of-government coordination and alignment with government priorities at the most senior level. The activities are also supported by several technical working groups on a variety of subjects, as well as other collaborative fora related to work on whale conservation.

Determining the interdepartmental governance structures for whale-related initiatives was challenging, as numerous committees and working groups were mentioned in interviews and referenced in documents. However, the structure is not clearly outlined in program documentation. In addition:

- some committees have terms of reference and meet regularly; others do not have terms of reference and it was not always clear whether the committee was meeting regularly;

- some committees are national in scope; others are region-specific; and

- some committees are species-specific, topic-specific, threat-specific, or departmental-specific.

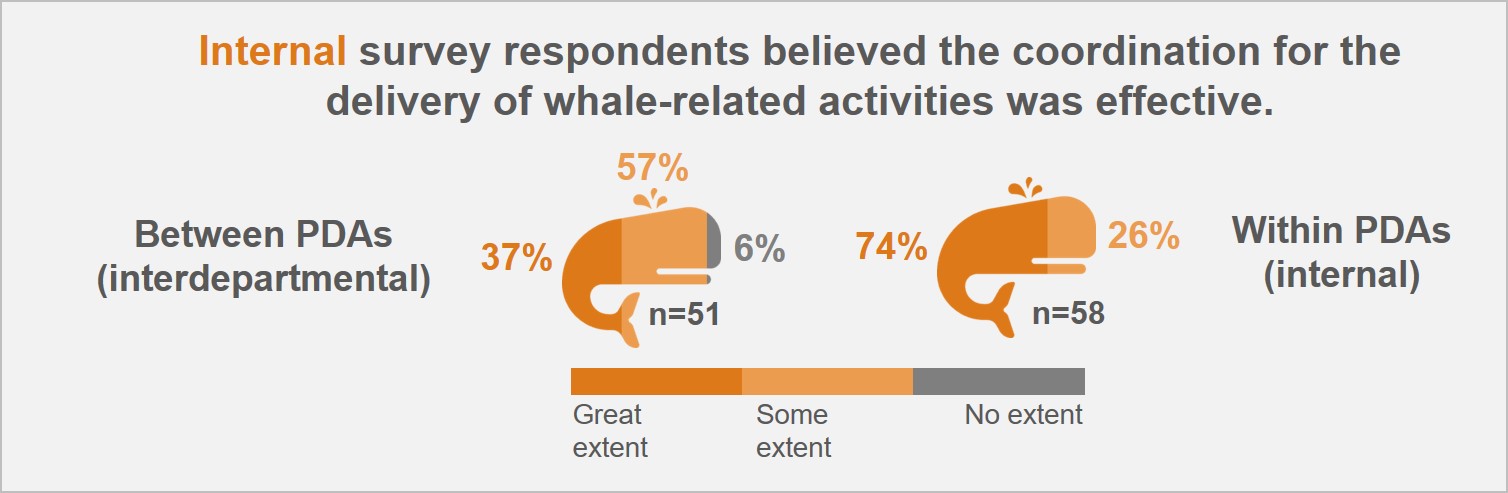

Despite the complexity and challenges related to the governance, overall, coordination for whale-related activities appeared to be effective. Internal survey respondents were positive about the coordination of the delivery of these activities, particularly within their own PDA.

Long description

A visual depicts two whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 51 internal survey respondents, 37% believed interdepartmental coordination was effective to a great extent, 57% to some extent and only 6% to no extent. Of 58 internal survey respondents, 74% believed internal coordination was effective to a great extent and 26% to some extent.

Internal survey respondents identified some complexity and aspects of interdepartmental governance that could be streamlined, such as clarifying leadership, roles and responsibilities and documentation for some activities. The fact that funding envelopes for whale-related activities were in addition to pre-existing funding might have contributed to challenges with interdepartmental governance, planning, and integration.

Internal survey respondents believed that collaborative opportunities within PDAs facilitated success. In addition, the technical working groups appear to have worked well, particularly those related to SRKW.

Long description

A visual depicts a whale shaped infographic that indicates that, of 48 internal survey respondents, 46% believed that coordination between PDAs facilitated achievement of desired results to a great extent, 52% to some extent and 2% to no extent.

Appendix C provides specific information on coordination and collaboration related to the four activities examined in-depth.

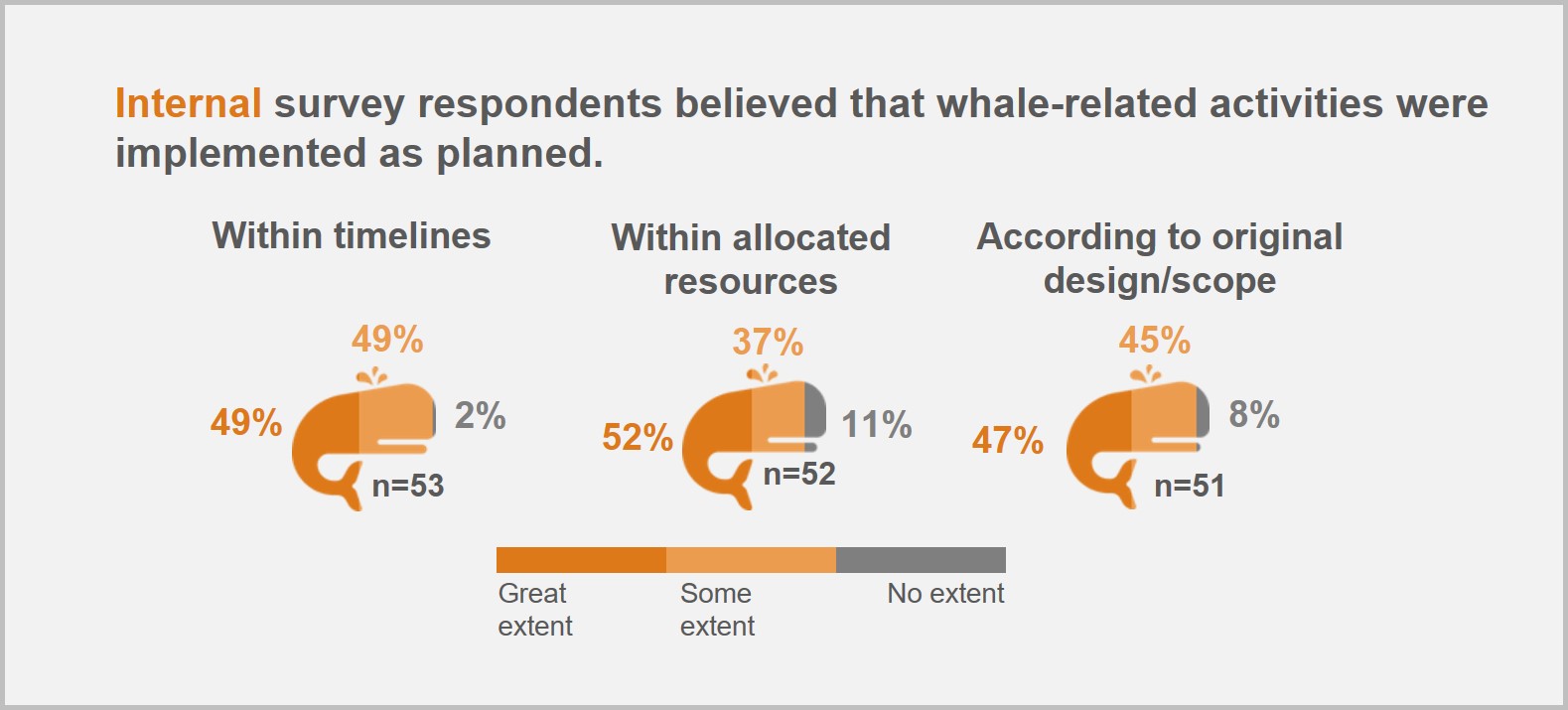

3.1.4 Implementation of activities

PDAs have undertaken a significant number of activities to support the protection and recovery of the targeted whale species, many of which were implemented as planned (i.e., within timelines and within dedicated resources). Measures and activities were planned using an adaptive strategy, which allowed for adjustments to activities based on sound advice, science, and Indigenous and stakeholder input.

Activities carried out under whale-related initiatives

The four PDAs have implemented a number of activities, which have been grouped into four categories for the purposes of the evaluation.

Research and monitoring

Objective: Monitor the threats and the presence, movements, and activities of the targeted whale species to provide information to support management decisions, regulatory controls and guidelines; develop technology to support these activities.

Activities:

- Conducted aerial surveys to detect whales.

- Installed underwater listening stations, gliders, hydrophones and Viking buoys.

- Monitored and researched various threats to the SLEB, SRKW and NARW (e.g., contaminants of concerns, prey availability, acoustic disturbance, effects of development and other potential and actual causes of mortality).

- Investigated innovative solutions for fishing gear, whale detection and monitoring and underwater noise reduction.

Management/mitigation measures

Objective: Implement targeted management measures to mitigate impacts and prevent threats to whales and their food sources.

Activities:

- Implemented measures, such as: area-based fisheries closures, slowdown zones, interim sanctuary zones, vessel approach distances, voluntary fishing avoidance zones, and gear marking requirements.

- Explored feasibility of using new fishing technologies (e.g., ropeless gear, weak points) and implemented mandatory reporting for lost gear and interactions between vessels or fishing gear and marine mammals.

- Conducted marine mammal response activities (e.g., disentanglement).

External partnerships, outreach, and education

Objective: Establish partnerships to facilitate the development and implementation of whale protection and recovery measures and carry out outreach and education to raise awareness and promote behaviour changes.

Activities:

- Worked with Indigenous communities and groups.

- Built partnerships with a range of different groups including: other government departments, other levels of government, and the private sector.

- Coordinated and partnered with research institutes, non-governmental organizations, and International organizations

- Conducted public awareness and education activities to promote the importance of recovery measures.

Compliance and enforcement

Objective: Carry out compliance and enforcement to ensure management measures are being respected.

Activities:

- Verified compliance with management measures and conducted enforcement activities.

- Conducted patrols and surveillance (i.e., aerial, on water)

- Issued warnings/notifications/penalties in cases of non-compliance; prosecuted cases, as needed.

- Conducted intelligence assessments to support and enhance enforcement activities.

Implementation status

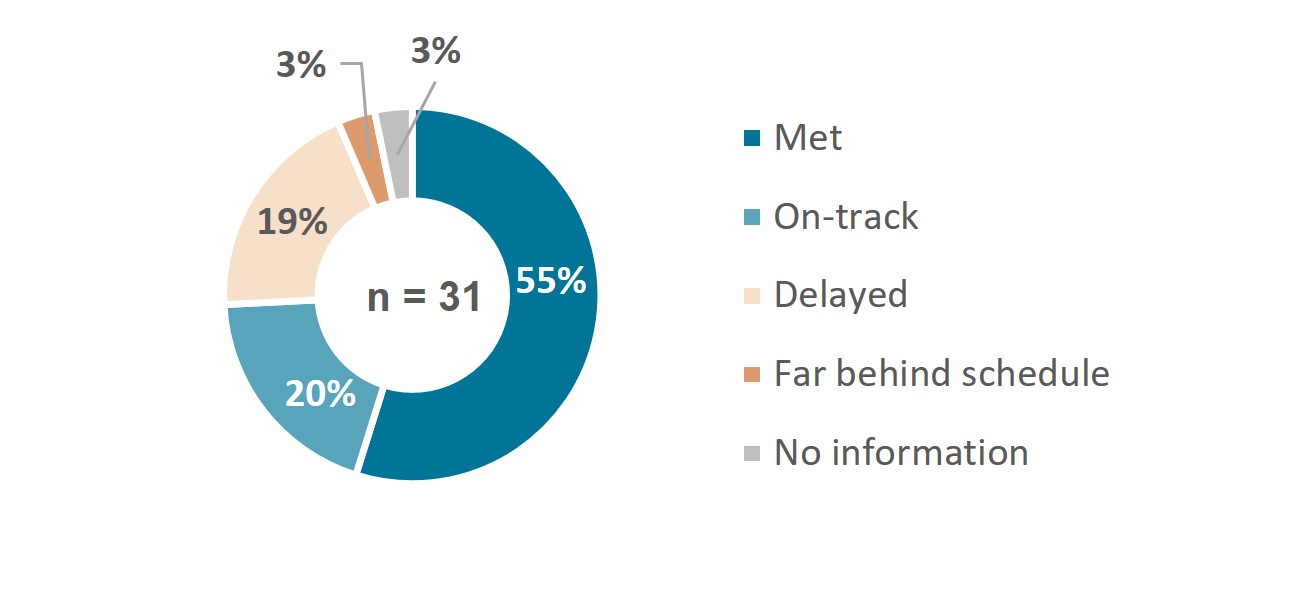

Program dashboard data on key implementation milestones for the whales and SRKW initiativesFootnote 12 showed that funded activities were largely implemented within timelines and within dedicated resources (Figure 2). Out of 31 milestones:

- 75% (n=23) of all milestones were either completed or are on track for completion.

- 22% (n=7) of the milestones were delayed, with many of the delays attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Long description

This figure depicts a donut shaped infographic that indicates 55% of key implementation milestones were met, 20% were on track, 19% were delayed, 3% were far behind schedule and the status of another 3% were unknown due to a lack of information.

Of the milestones that were delayed, the most notable was the purchase and refurbishment of an airplane for whale monitoring, which was planned for 2020 but was delayed to March 2023 largely due to contracting difficulties and supply chain issues. Underwater noise management plans were also delayed due to the need for additional tests to determine the most appropriate metrics for noise reduction targets to inform further the development of the plans. In addition, the initial timelines for co-development activities with Indigenous communities and groups were also found to have been unrealistically short, in addition to being impacted by the pandemic.

Long description

A visual depicts three whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 53 internal respondents, 49% believed that activities were implemented within timelines to a great extent, 49% to some extent, and 2% to no extent. Furthermore, of 52 internal respondents, 52% believed that activities were implemented within budget to a great extent, 37% to some extent, and 11% to no extent. Lastly, of 51 internal respondents, 47% believed that activities were implemented according to the original design/scope to a great extent, 45% to some extent, and 8% to no extent.

Variations from initial plans

When the whale-related initiatives were launched, it was not known exactly what activities and measures would be needed. Thus, significant flexibility was built into the funding to allow for adjustments based on sound advice, solid science, surveillance, and feedback from stakeholders and partners. Nevertheless, the evaluation did not find significant variations from planned activities and timelines.

- Many activities were implemented earlier than planned (e.g., slow-down areas and related engagement for NARW, contracts to support partners of the marine mammal response program, creation of technical working groups for SRKW).

- There was more significant progress regarding knowledge generation for NARW. Initially, there was less initial science data available for that species and thus the need to generate data was greater. In comparison, SRKW and SLEB had previous activities funded through other sources.

- Implementation of some management measures occurred dynamically as well, in response to active monitoring through aerial surveillance, hydrophones/gliders, AIS data on ship movements, and other sources.

3.1.5 Challenges related to implementation

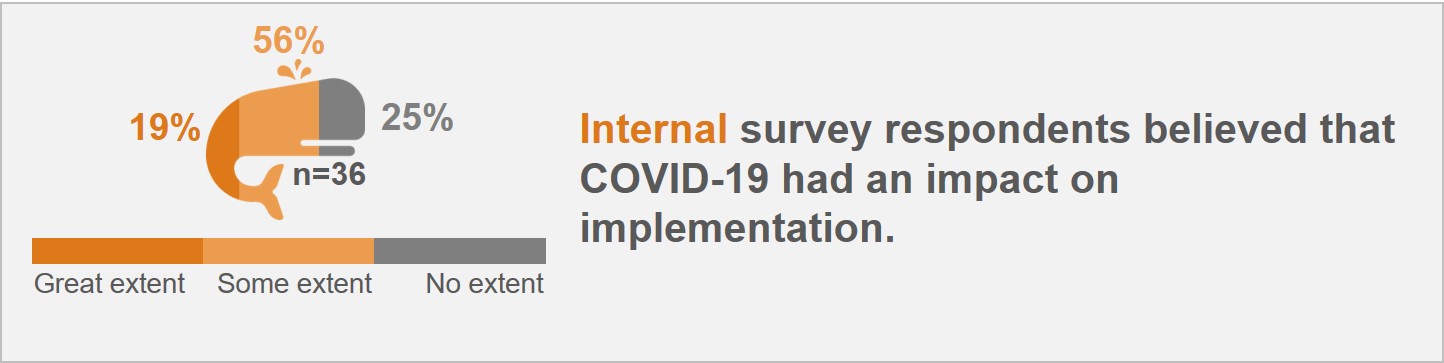

PDAs faced some challenges during implementation, particularly with respect to COVID-19 and capacity, which affected the implementation of some planned activities.

Challenges related to implementation of activities

PDAs faced some challenges that affected their ability to carry out certain activities. In some cases they were able to adapt to and mitigate these challenges, but others were outside of their control and had an impact on the completion of some activities.

COVID-19-related impacts

- Some of the PDA’s planned fieldwork/data collection was delayed due to the inability to travel; and the use of labs to support COVID-19 testing limited lab space for whale-related analysis.

- Some of the new real-time NARW detection technologies could not be tested as planned. To mitigate this, equipment was tested in areas with no NARW, using manufactured sounds as a proxy for whale calls, which was not as ideal.

- The in-person interpretation in national parks was limited, which impacted the delivery of SRKW educational programs, including the gathering for engagement and learning. Furthermore, extended timelines were required to incorporate First Nations content in interpretive signs.

The pandemic impacted the staffing of the refurbishment workshop, thus further delaying the refurbishment of some equipment, such as the TC Dash 8 aircraft.

Long description

A visual depicts a whale shaped infographic that indicates that, of 36 internal respondents, 19% believed that COVID-19 had an impact on implementation to a great extent, 56% to some extent, and 25% to no extent.

See Appendix C for specific challenges and factors that had an impact on the four activities examined in-depth.

Capacity-related impacts

The significant investments for endangered whales provided additional capacity to PDAs to implement activities related to the protection and recovery of whales. However, there was evidence that resourcing and staffing challenges remained.

Long description

A visual depicts two whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 48 internal respondents, 38% believed that a lack of program staff had an impact on implementation to a great extent, 50% to some extent, and 12% to no extent. Likewise, of 50 internal respondents, 20% believed that insufficient funding had an impact on implementation to a great extent, 66% to some extent, and 14% to no extent.

There were numerous impacts related to these challenges.

- Many program areas (e.g., fisheries management, enforcement, outreach and education, communications, policy, science) had to use funding from other program areas (e.g., OPP) and/or risk manage funding.

- Where additional funding could not be redirected to whale-related activities, work was kept to a minimum or limited to the highest priorities.

- Building internal expertise was a challenge, which was partially addressed by the expertise of the technical working groups.

- Resources were not allocated for administration and secretarial functions, thus, causing coordination and reporting challenges. This also had an impact on other activities (e.g., subject matter experts were taken away from their work to fulfill this role).

Limitations with CCG vessel availability also led to delays and postponements for some planned DFO fieldwork for NARW and reduced the scope of work for shipping noise impact assessments.

3.1.6 Indigenous involvement in whale-related programming

The three targeted whale species are significant to Indigenous Peoples’ cultures, communities, and the ecosystems on which they rely. PDAs put processes in place to engage Indigenous communities and groups in whale-related programming; however, their degree of involvement in these processes varied. Several areas for improvement to the engagement and consultation processes were identified by Indigenous communities and groups.

Significance of whales to Indigenous Peoples

First Nations on the Pacific coast and representatives of Indigenous groups from the Atlantic coast explained the significance of the whales to their cultures, communities, and the overall marine ecosystem.

On the Pacific coast, some First Nations explained the spiritual connections they have with the SRKW and said that they regard them as relatives. Others shared that the whales feature prominently in their songs, oral traditions, art, and ceremonies. Representatives spoke with great concern for the health and recovery of the SRKW and agreed the species’ protection was a priority given the integral role it plays in their cultural identity and the health of the ecosystem.

“Historically they are known as Blackfish. They are the health of the waters made manifest. They are powerful beings whose spirits count for more than any development, any amount of imaginary wealth, any illusion of power and dominion over nature... Of all marine species they have some of the closest ties to [us].”

– Representative from Pacific region First Nation

Representatives from Quebec and Atlantic Canada prefaced their perspectives with the fact that they were not Indigenous themselves, rather working for Indigenous groups. Nevertheless, they spoke of the targeted whale species being a barometer of health for the entire ecosystem and were concerned about their long-term survival.

Those located along the St. Lawrence Estuary spoke of the importance of the beluga harvest to the diet and trade of the First Peoples of the region, while being loved and revered by present-day communities.

“The beluga is a strong species…[and] it is a species of importance for the community. People love to observe marine mammals and the beluga is particularly important.”

– Representative from Quebec region Indigenous group

Representatives in Atlantic Canada shared that the NARW held cultural importance to the Indigenous communities and groups in the region, playing key roles in their legends.

“The People and the North Atlantic right whale have a strong connection. North Atlantic right whales were seen as masters of life in the sea, and they are a part of First Nation legends and stories. The People won’t put a hierarchy on living creatures, but NARW do have a cultural significance to the People in the area.”

– Representative from Atlantic region Indigenous group

Expectations for engagement and consultation

At the outset of whale-related initiatives, Indigenous communities and groups recommended that the government clearly define the engagement and consultation processes and allow for substantial opportunity for two-way dialogue and broad representation of perspectives.

Indigenous communities and groups also requested timely and transparent sharing of information to support joint decision-making and to ensure measures put in place were justifiable. In addition, they wanted to be engaged early in the process to ensure time for their input to be integrated into final decision-making. Finally, they requested their participation be supported by dedicated and non-competitive funding to ensure ongoing and meaningful involvement in whale protection and recovery efforts.

Engagement approaches

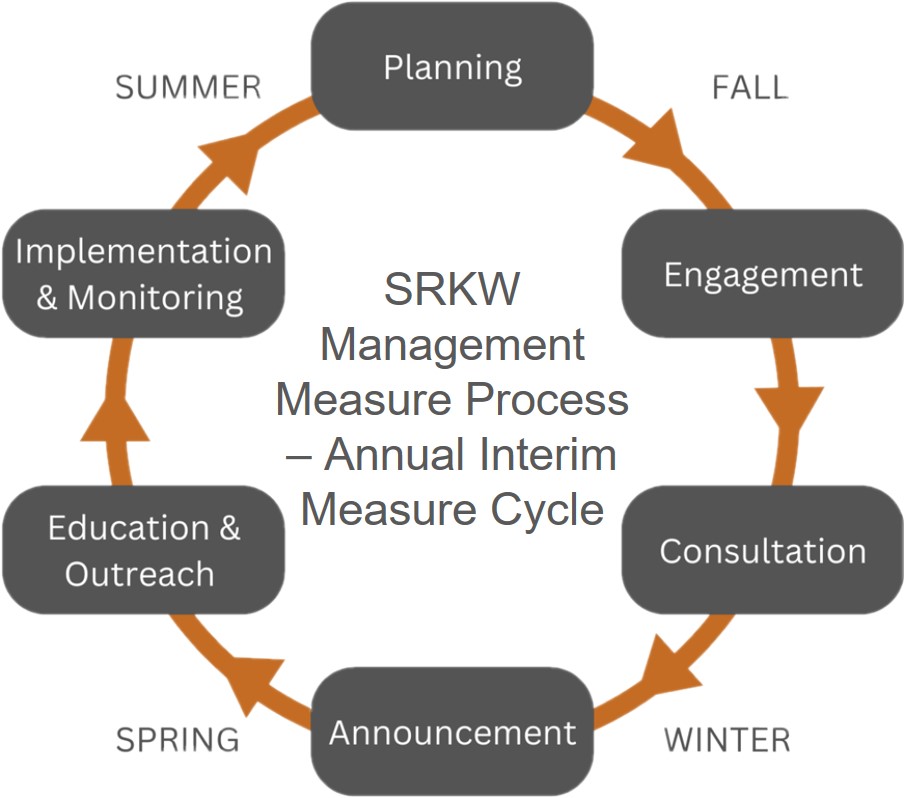

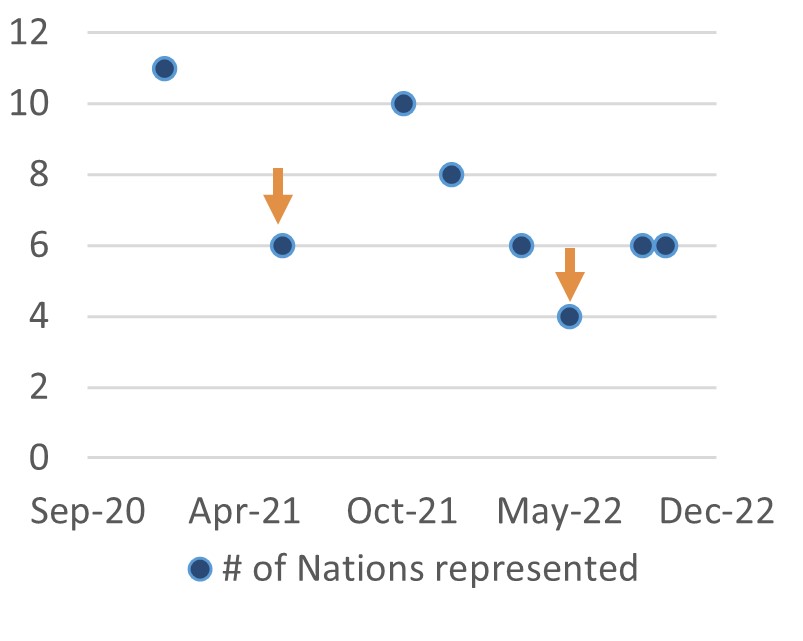

The government’s engagement and consultation processes with Indigenous communities and groups varied by region. On the Pacific coast, all 37 First Nations who had the potential to be impacted by the SRKW annual interim measures were approached to discuss the development and implementation of annual measures (see Appendix B for the full case study on Indigenous involvement in the SRKW Initiative).

Methods of engagement and consultation with the Nations varied by year with evidence suggesting improvements were made based on feedback. For example, in the Pacific region, a multi-Nation Tier I and II process (see box 3 below) was established in response to feedback from Nations and to complement the official consultation process. The extent of engagement in the processes depended on several factors specific to each Nation, such as:

- the spiritual and cultural significance of the SRKW to their people;

- the extent to which their marine territory overlapped with the geographical scope of the management measures;

- their community priorities; and

- their capacity to participate in engagement activities.

Box 3: SRKW Tier I and II multi-Nation process

In late 2020, a Tier I and II multi-Nation process was developed, with the first meeting taking place in spring 2021. The meetings were facilitated by an Indigenous consultant and were guided by a co-developed framework for cooperation and collaboration for SRKW management measures. The Tier I meetings were reserved for First Nations only, while representatives from the PDAs joined the Tier II table. The purpose of the process was to support nation-to-nation and Government of Canada-to-nation dialogue to inform the development and implementation of the SRKW management measures prior to engagement with stakeholders. The process also supported information sharing and facilitated connection to other Government of Canada processes relevant to SRKW recovery.

Engagement and consultation in Quebec and Atlantic Canada was more limited and ad hoc than the approach used in the Pacific region. Some examples of engagement activities were provided (e.g., participation in discussions on NARW-related measures and activities, involvement in the development and dissemination of educational materials).

It was noted by representatives on the Atlantic Coast that Indigenous communities and groups seemed to initiate engagement rather than being invited to existing tables by PDAs (e.g., requesting seats on working groups). Representatives also indicated an ongoing need for Indigenous fishers to be included in discussions on ghost gear and entanglement prevention.

PDAs did note that engagement on whales did not initially seem to be of significant interest, as when they did attempt to consult Indigenous communities and groups in Quebec and Atlantic Canada, their efforts were not always successful. For example, when zones became restricted to all vessels, TC attempted to engage and discuss with Indigenous fishers, however none responded. PDAs did note that more recently there seems to be a growing interest.

Satisfaction with engagement and consultation processes and opportunities for improvement

The level of satisfaction with the engagement and consultation processes varied by Indigenous community and group, with evidence suggesting that PDAs attempted to respond to feedback and concerns raised by First Nations on the Pacific coast.

Each year, Indigenous communities and groups called on the PDAs to effectively consult and meaningfully involve them in whale-related programming. As previously indicated in Box 3, the multi-Nation Tier I and II process was established in the Pacific region to enhance engagement and complement the official consultation process. While the Tier I table was deemed of value to some First Nations as a forum for frank and effective discussion between Nations, participation in the Tier II table varied by season and decreased year over year. Reasons noted for this low attendance included:

- inadequate notice of meetings and insufficient time for in-depth and meaningful discussion;

- a lack of transparency on how previous input had been included in decision-making;

- a lack of financial support for Nations to participate in the process; and

- the fact that the multi-Nation process did not meet the Government’s duty to consult. As a result, some prioritized bilateral discussions over other engagement opportunities.

Furthermore, several First Nations disagreed with the consultation approach adopted by the PDAs and many Nations felt engagement processes prioritized views of industry and occurred too late in the annual review process, only after key decisions had been made. First Nations called on the PDAs to address these concerns to establish a more cooperative approach, improve attendance, and ensure more broad representation at meetings.

On the Atlantic coast, some representatives noted satisfaction with the approach to engagement (e.g., invitations to participate were timely; opportunities to meet as Indigenous communities and groups separate from others, were appreciated). However, there was a desire to have more frequent opportunities to meet with other partners to discuss whales programming. The evaluation team noted evidence of very few forums involving Indigenous communities and groups in discussions around NARW and SLEB protection and recovery. Some representatives interviewed offered suggestions to improve the engagement sessions, including moving away from highly technical briefings to explore more appealing and digestible ways to engage Indigenous communities and groups and facilitate rich and fruitful discussions.

3.2 Progress addressing threats

3.2.1 Measuring progress in addressing threats

How progress was measured

The evaluation aimed to assess the extent to which progress was made in addressing threats to the targeted species. Many whale-related activities funded since 2018 largely focused on:

- monitoring and data collection to establish baseline information on the current characteristics of the whales’ habitats or level of impact threats are having;

- scientific activities to increase the knowledge base on whale-related risks and on potential interventions to address those risks; and

- testing hypotheses and new technologies to support decision-making.

Multiple cycles of data collection, analysis, and testing are required before sound scientific advice will be available for decision-making on measures. Consequently, while these activities did not directly reduce the impacts of threats, they were undertaken to gather the information and data needed to inform and support the implementation of management measures, which are intended to mitigate the threats to whales.

Long description

This figure depicts the results cycle for whales related activities. At the beginning of the cycle, there is the collection of new data. Next, there is the research and analysis of this new data, followed by the implementation of measures. The cycle ends with the mitigation of threats before beginning again with the collection of new data.

Limitations with measurement

There are a number of challenges and limitations to determining the extent to which progress was made toward protection and recovery of the whales, including:

- lack of baseline data against which to measure progress (in fact, many funded activities were intended to establish these baselines);

- challenges in defining performance measures that would accurately assess threat mitigation, as well as considerable progress (e.g., there are no established thresholds of the severity of threats, long-term health and life outcomes for whales cannot be measured by population size as there are many other factors affecting the population); and

- it could take many years to gather enough data to determine and observe progress.

Box 4: Other factors to consider when assessing progress in addressing threats

- Evolving environmental factors (such as climate and ocean conditions) could influence whale habitat and behaviour in a way that is hard to predict accurately when measures are implemented and this could affect expected effectiveness.

- The long-term nature of most interventions and the long life cycle of target species in terms of recovery.

- Disturbances and other threats that originate from outside Canadian waters.

- Threats that cannot be fully eliminated but only reduced to a tolerable level (e.g., pollution, vessels noise).

- Socio-economic and cultural contexts (i.e., measures should not be assessed in isolation from their impacts to the Canadian economy or to the coastal communities).

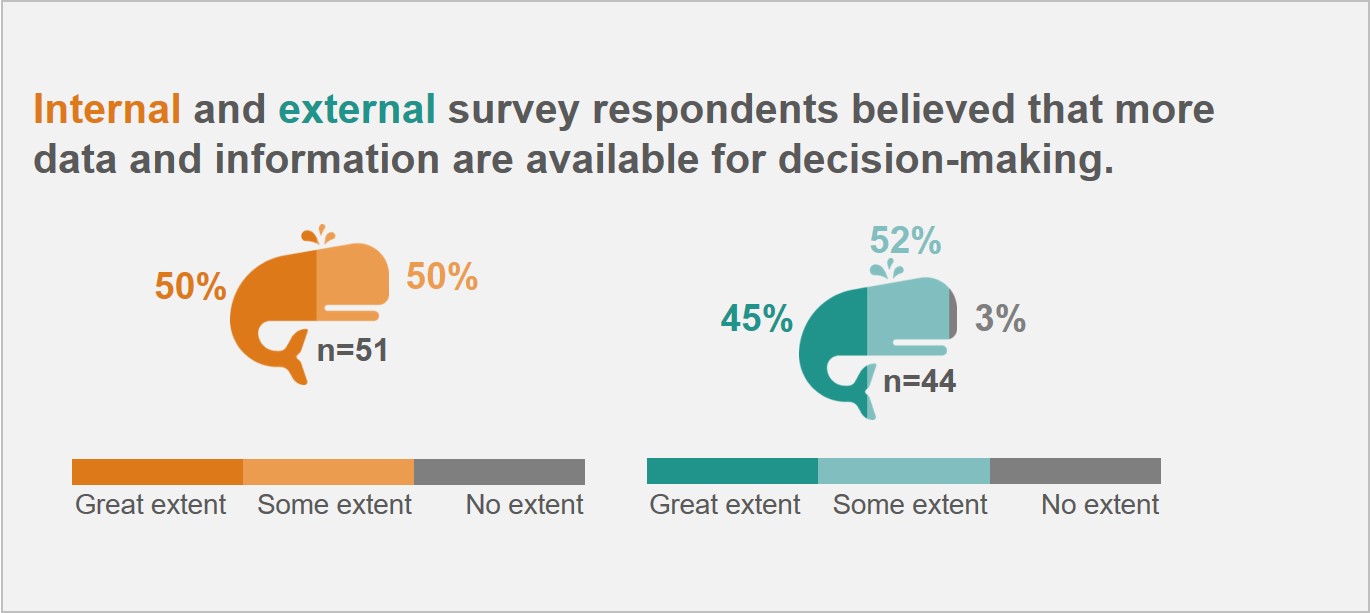

3.2.2 Availability of new data and information

The knowledge base to support decision-making related to whale protection and recovery has increased significantly as a result of new data collection, monitoring, Indigenous Knowledge and Science, and scientific research activities.

Collection of new data

Overall, there is strong evidence that new data and information is available to support decision-making as a result of the investments, which has resulted in an increase in the knowledge base related to whale protection and recovery.

Long description

A visual depicts two whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 51 internal survey respondents, half believed that more data and information was available to a great extent and the other half believed to some extent. Of 44 external respondents, 45% believed that more data and information was available to a great extent, 52% to some extent, and 3% to no extent.

Specifically, there is now more information available on whale detection. Funding was provided for whale-specific aerial surveillance, which is conducted by several different partners, including: DFO Science, DFO Conservation and Protection (C&P) Fisheries Aerial Surveillance and Enforcement (FASE) program, TC’s National Aerial Surveillance Program (NASP), and TC’s Remote Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS). Together, between 2018-19 and 2021-22 partners reported 10,682 hours of whale-specificFootnote 14 aerial surveillance. The breakdown of these hours by partner and program included: 5,446 hours through DFO Science; 3,557 hours through the DFO Conservation and Protection FASE program; 1,509 hours through the TC NASP; and 170 hours through the TC RPAS program.

Acoustic monitoring also increased the availability of information, including on whale detection and noise levels from vessels. Acoustic monitoring has been done through the deployment of acoustic monitoring stations, gliders, and Viking buoys. There were four acoustic monitoring stations, including an underwater listening station in Boundary Pass, and there were seven Viking buoys. There were also four glider deployment missions in three general locations for a total of 376 days in 2019, 2020 and 2021.

In addition to the detection and noise data, other new information available includes: whale behavioral data, vessel transit data, contaminant-sampling data, toxicological reports, photogrammetry datasets, and data tracking and visualization tools.

On the Pacific coast, near-real time monitoring and whale detection verification capacity was not funded under the Whales or SRKW Initiatives, so other programs were leveraged and funding risk-managed to meet these needs.

Research and analysis of new data

Review of performance data showed that most targets for science products have been met or exceeded, with the exception of a few that were on track but required more time to be completed.

Between 2018-19 and 2021-22, a number of new Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS)Footnote 15 advisory reports and scientific publications on whales were made available. These reports and publications included: 14 CSAS products and advisory reports; nine Peer-reviewed publications on stressors and impacts of shipping on marine life and their habitat; 41 peer-reviewed publications on SRKW, NARW, and SLEB; and 12 Monitoring data reports on contaminants of concern in whale habitats.

These reports focused on several areas, including:

- developing scientific advice on marine ecosystems applicable to SRKW, NARW, SLEB, and their prey;

- testing new technologies for acoustic or aerial monitoring and detection, such as static hydrophones, near real-time systems, gliders and the RPAS;

- assessing the effects of vessel noise reduction technologies and vessel noise/vessel strike mitigation; and

- monitoring the presence and assessing effects of contaminants in whales’ habitats.

Input from surveys and interviews confirmed that, as a result of research and monitoring activities, in general, the Government of Canada is in a better position to take protective actions, based on knowledge and scientific evidence. CSAS advisory reports and studies were specifically acknowledged as being instrumental for decision-making; however, some studies required more time and are still in progress.

Box 5: Examples of scientific areas with significant knowledge increase

- Better understanding (in terms of precision and accuracy) of the SRKW habitat (e.g., identification of important transit and foraging zones, migration patterns) and forage fish habitats and prey availability for SRKW.

- Information on NARW distribution and ability to model NARW distribution in critical areas along vessel routes, as a result of aerial surveys, acoustic monitoring, and analysis of AIS data.

- Modelling the effects of management measures for noise reduction and further research on new noise reduction technologies.

- Geospatial inventories of contaminated sites in areas of interest; and of potential sources of pollutants and estimated releases in areas of interest.

For examples of Indigenous Knowledge being woven into the whale-related programming, see Appendix B.

3.2.3 Accessibility of data and information

Note: Accessibility refers to the ease with which users are able to identify, obtain and use data and information, which correspond to their needs.Footnote 16

While there has been a significant increase in the availability of information for decision-making, there is room for improvement in terms of the accessibility, integration, and sharing of data to facilitate its use. In addition, the research and monitoring work undertaken over the past five years does not address all existing and emerging information needs. Data and information gaps will always remain, and the process of addressing them is ongoing.

Much of the information and science products that are now available as a result of whale-related monitoring and research activities are accessible on the websites of the PDAs.

- CSAS advisory reports are posted on CSAS’s publications site.Footnote 17

- Other scientific studies and reports are published in peer-reviewed journals.

- Known locations of whales (mostly on the Atlantic coast) are displayed on two interactive mapping tools: Whale MapFootnote 18 developed in 2018; and DFO’s Whale InsightFootnote 19, launched in May 2022. Acoustic and visual detections from whale-related monitoring and surveillance activities, as well as from other trusted sources (such as NOAA) are the sources for these maps.

- ECCC has developed the online PAWPIT toolFootnote 20 as an interactive inventory and map of pollutants and their sources in the habitat of endangered whales and their prey. It covers only the SRKW habitat areas and a version for SLEB is in development.

Challenges related to data and information accessibility

While these tools were described as useful, many interviewees and survey respondents expressed concerns that finding, extracting, and using specific data for their work was challenging (e.g., different types of data were disseminated in different formats, and through different platforms and web applications).

Some other limitations with regards to availability of data and information were identified, such as the time needed for official peer-reviewed publication of scientific reports and related data before they become available, which delays their use. There was also perception of missed potential opportunities to increase the use of data and information produced by non-federal scientists, which could speed up the implementation of some measures.

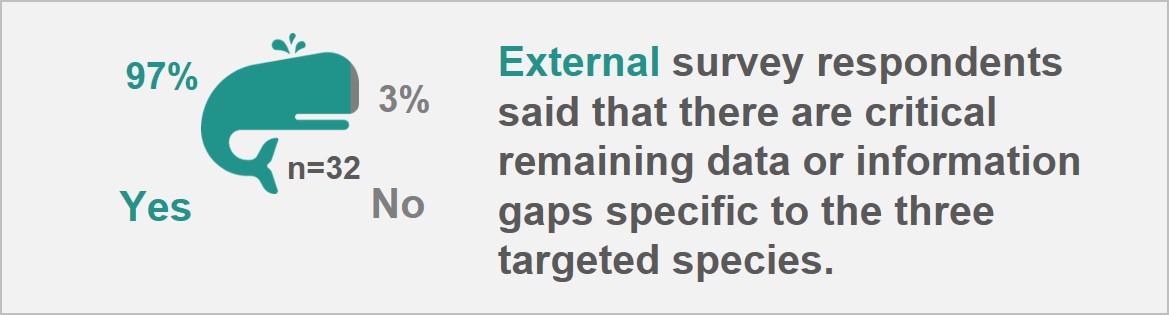

3.2.4 Remaining data and information gaps

Despite the success of the research and monitoring work and increased data and information, there will always be some existing and emerging data and information needs, because current knowledge has to be continuously updated to reflect newer scientific studies and information, as well as the evolving factors of environment. Almost all experts who responded to the external survey agreed that critical data and information gaps remain. Looking forward, the evaluation identified broader areas for additional data and research, as well as whale-specific data gaps (these are summarized below).

Long description

A visual depicts a whale shaped infographic that indicates that, of 32 external survey respondents, 97% said that there are critical remaining data or information gaps.

Broader areas for additional data and research

Continuous update and improvement of the knowledge base for decisions on management measures

- For proper coverage and detection across two oceans, more monitoring and surveillance locations are needed; in addition to covering the same locations over time.

- Interdependencies between different threats and the cumulative effects of interventions to one or several threats need to be better studied and understood.

Assessing effectiveness of measures

- Data and analysis on enforcement and non-compliance, and ongoing monitoring and assessment of how the measures work, to inform their fine-tuning and improvement.

- The actual recovery feasibility (e.g., likelihood of recovery) is an important gap which affects priority setting and the assessment of measures’ feasibility.

- Data and information on whale presence and threats exposure outside Canadian-monitored waters is another important gap that affects implementation of measures that are most appropriate.

Changing factors of whale habitats

- Ongoing changing environmental conditions require continuous data gathering, monitoring and research to support the adaptation of management measures to the changes in the threats and risks to whale habitats (e.g., the effects of a warming, a more acidic ocean).

- There are new emerging needs with regards to studying contaminants for whale protection (e.g., geographic areas of contaminants in whale habitats not studied before).

Whale-specific data gaps

SRKW

- Foraging studies and enhanced understanding of prey availability in finer scale resolution in space and time are needed in more geographic areas.

- Advancing real-time monitoring and studies of effects of physical disturbance, acoustic noise and vessel noise thresholds are needed.

- Need for more monitoring of contaminants in SRKW prey habitats, including those discharged through landfill leachate and wastewater treatment systems.

- Increasing the value of data and information by weaving Indigenous Knowledge and western science (e.g., on salmon and vessel traffic locations).

NARW

- Better understanding of threats related to NARW prey availability.

- Integrating cryptic mortality (i.e., the unrecovered whale carcasses) in the threat analysis for NARW, to improve accuracy of assessments on the severity of risks.

SLEB

- Data and information on SLEB seem to be the least available. Research done to date has increased data available on diet and seasonal changes in distribution before and after summer; however, it is only the first step in identifying critical SLEB habitats.

- More field work and modelling efforts are needed to determine measures that are appropriate and effective for SLEB.

- There is a need for more pollution monitoring in the Saguenay River and freshwater monitoring for contaminants to SLEB, including those being discharged through landfill leachate and wastewater treatment systems.

3.2.5 Appropriateness of funded activities

While it is early to assess the full effectiveness of some measures, the activities funded to support whale protection and recovery were viewed as appropriate to achieve results.

Appropriateness of activities to achieve results

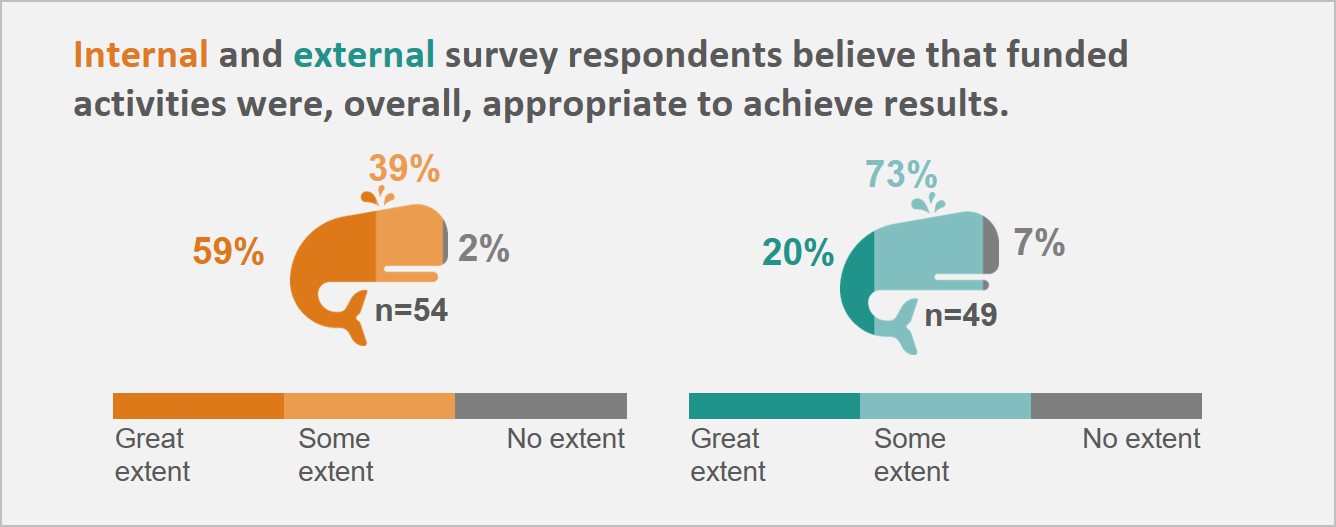

Overall, the evaluation found that funded activities were viewed as appropriate to achieve desired results related to whale protection and recovery. External survey respondents believed it to a slightly lesser extent than internal survey respondents.

Long description

A visual depicts two whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 54 internal respondents, 59% believed that funded activities were appropriate to a great extent, 39% to some extent, and 2% to no extent. In addition, of 49 external respondents, 20% believe that funded activities were appropriate to a great extent, 73% to some extent, and 7% to no extent.

Stakeholders noted that assessing effectiveness is challenging because more research and more time is needed to fully understand how well measures are working. In addition, there are challenges in measuring recovery of the whale populations.

Furthermore, both internal and external stakeholders were in agreement that enforcement is an appropriate and important activity, however, they also noted that the ability to conduct adequate enforcement to support the measures was hampered by both capacity issues and enforceability challenges in the measures themselves.

In terms of additional activities or measures that could be implemented to support whale protection and recovery, it was noted by a few stakeholders, mainly external, that regulations are needed with respect to whale watching.

Some external stakeholders expressed concerns with regards to some of the funded activities/measures not being the optimal way to address whale protection and recovery. These are summarized below.

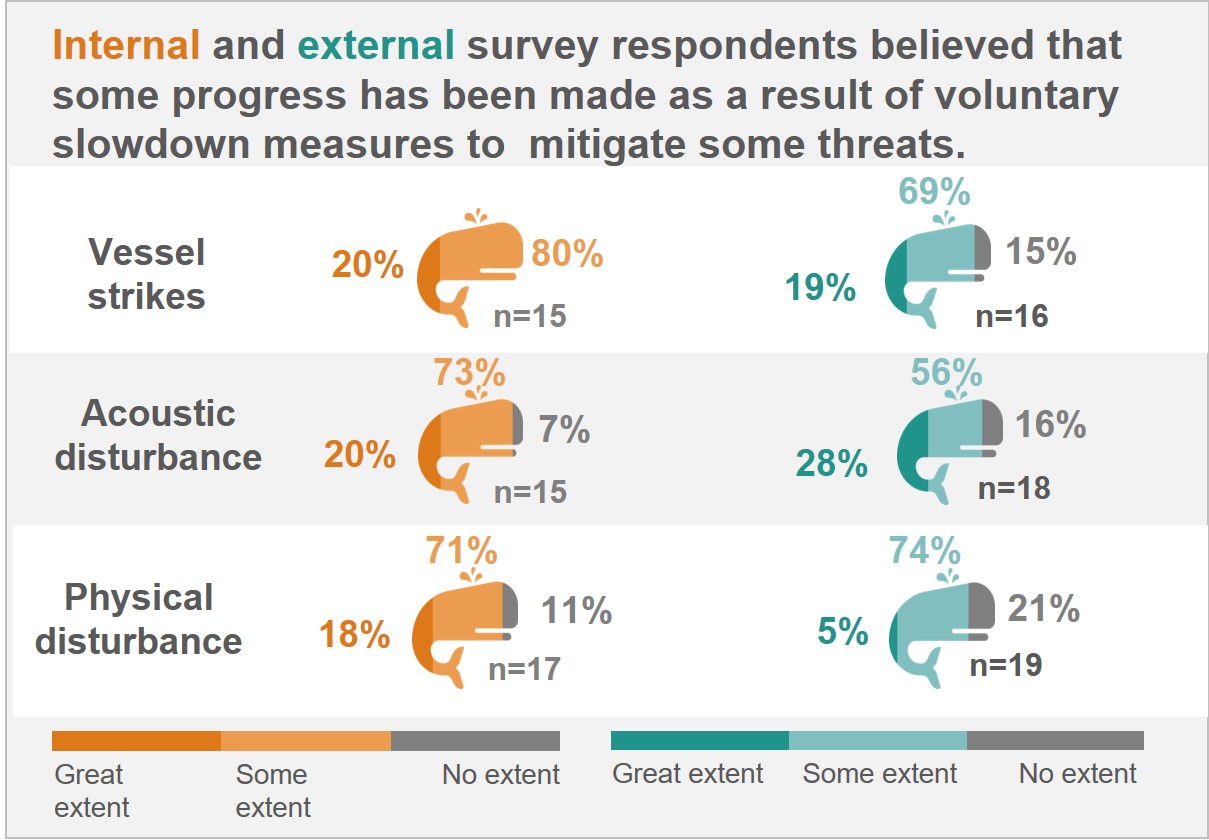

- Voluntary slowdown measures, in general, are less effective than mandatory measures; there is insufficient scientific evidence on the optimal slowdown speeds (see Appendix C for more details).

- Fisheries closures are not viewed as effective if triggered after whales are detected, they have limited effectiveness on populations that are very mobile such as the SRKW, and have not been effective in increasing prey availability. Some fisheries closure dynamic areas were also questioned by some industry members as being outdated, inaccurate, or poorly delineated.

- Interim sanctuary zones have limited effect because they have not covered essential foraging zones. Additionally, implementing new ones is challenging in terms of social acceptance.

- Whale approach distances currently in place are based on scientific evidence that is viewed as inconclusive.

A few stakeholders also suggested that, while some of the activities were appropriate, their scope was too limited. It was suggested that some activities (e.g., noise monitoring and whale detection), should be expanded (e.g., additional geographic areas, more species).

The following sections provide additional detail on the evaluation findings related to the observed changes and progress on addressing threats. Appendix C includes specific detail on progress made by the four activities examined in-depth.

3.2.6 Evidence of progress made

Progress has been made on mitigating risks to whales. There has been more significant progress in reducing entanglements and vessel strikes compared to progress addressing other threats (e.g., prey availability, acoustic disturbance, and contaminants), which typically require more time. However, there is more work to be done in areas such as compliance and enforcement, scope of activities, partnerships and engagement, and threat mitigation performance measurement.

Evidence of progress made

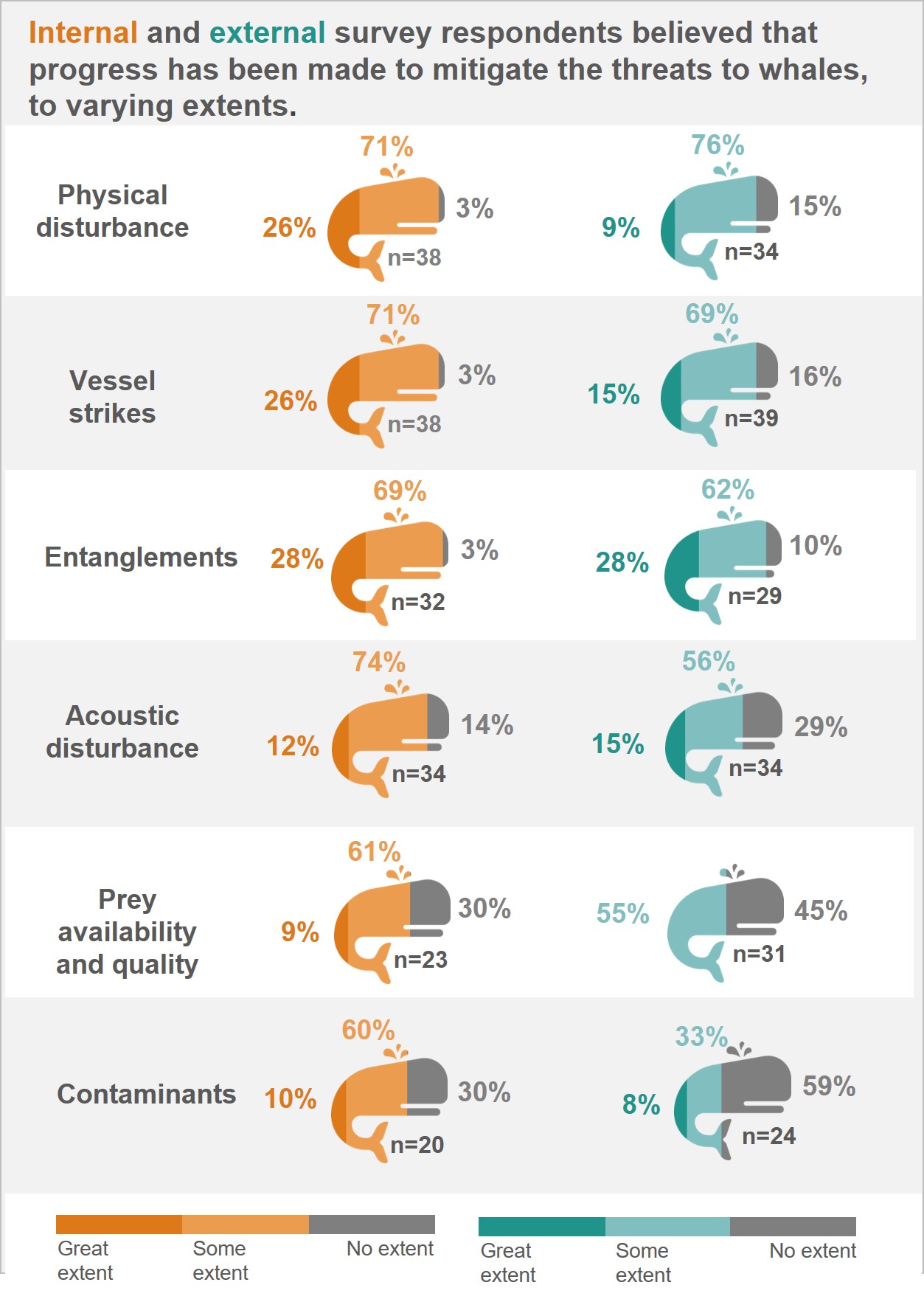

Various documents and data reviewed, and survey responses, provided evidence of some progress made on mitigating risks to whales as a result of measures, although opinions varied by threat. Overall, internal respondents had more positive views than external respondents.

Long description

A visual depicts twelve whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 38 internal respondents, 26% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of physical disturbance to a great extent, 71% to some extent, and 3% to no extent. By comparison, of 34 external respondents, 9% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of physical disturbance to a great extent, 76% to some extent, and 15% to no extent.

For the threat of vessel strikes, of 38 internal respondents, 26% believed that progress has been made to mitigate this threat to a great extent, 71% to some extent, and 3% to no extent. By comparison, of 39 external respondents, 15% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of vessel strikes to a great extent, 69% to some extent, and 16% to no extent.

Of 32 internal respondents, 28% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of entanglement to a great extent, 69% to some extent, and 3% to no extent. Similarly, of 29 external respondents, 28% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of entanglements to a great extent, 62% to some extent, and 10% to no extent.

For the threat of acoustic disturbances, of 34 internal respondents, 12% believed that progress has been made to mitigate this threat to a great extent, 74% to some extent, and 14% to no extent. By contrast, of 34 external respondents, 15% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of acoustic disturbances to a great extent, 56% to some extent, and 29% to no extent.

Of 23 internal respondents, 9% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of prey availability and quality to a great extent, 61% to some extent, and 30% to no extent. In comparison, of 31 external respondents, 55% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of prey availability and quality to a great extent and 45% to some extent.

Lastly, for the threat of contaminants, of 20 internal respondents, 10% believed that progress has been made to mitigate this threat to a great extent, 60% to some extent, and 30% to no extent. By contrast, of 24 external respondents, 8% believed that progress has been made to mitigate the threat of contaminants to a great extent, 33% to some extent, and 59% to no extent.

Physical disturbance, vessel strikes, and entanglements were viewed as the threats that have been addressed to the greatest extent and some examples were provided (see Appendix C for more examples and data).

- Increased outreach and education regarding vessel management measures (e.g., approach distance limits, seasonal slowdowns, interim sanctuary zones) helped reduce vessel strikes and physical disturbance for both SRKW and NARW.

- Fisheries management measures (e.g., opening the fishing season earlier, closures protocols when NARW in area, whalesafe fishing gear, gear marking, lost gear reporting requirements) contributed to entanglement prevention.

- The whale-related capacity within the marine mammal response program has increased, both in the regions and nationally. As a result, progress was made to improve incident response protocols and procedures and to increase training.

Prey availability, acoustic disturbance, and contaminants were viewed as threats that are more challenging to address and require more time to see results. Examples of areas where some progress was made were provided.

- Understanding of the types and presence of pollutants affecting whales and their prey has increased; but implementation of mitigation measures is slow and not enough time has passed to see long-term results.

- Implementing voluntary vessel slowdown measures as part of the ECHO program (see box 6 below) has been promisingNote de bas de page 21. On the Pacific coast, the measures were successful over the past three years (with >80% compliance). They were effective in shared U.S./Canada waters, where Canada has no authority for mandatory measures, because the voluntary regime could cover greater area. However, their efficacy is dependent on voluntary compliance (which is impacted by economic factors), and no enforcement measures can be taken in case of non-compliance because no statutory requirements to comply exist.

- In 2021, the SRKW Accountability FrameworkNote de bas de page 22 was developed to assess how the management measures were contributing to SRKW recovery over time.

Box 6: Example from the ECHO Program

The ECHO ProgramNote de bas de page 23 is a collaborative regional initiative led by the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority. It was launched in 2014 and is guided by the input and advice of government agencies, the marine transportation industry, Indigenous advisors, and environmental organizations.

On May 10, 2019, a 5-year conservation agreement to support the recovery of the SRKW was signed by nine partners, including DFO, CCG, and TC, which formalized the participation of all parties in the ECHO Program, towards the shared goal of reducing acoustic and physical disturbance resulting from large commercial vessels operating in SRKW critical habitat in the Pacific Canadian waters.

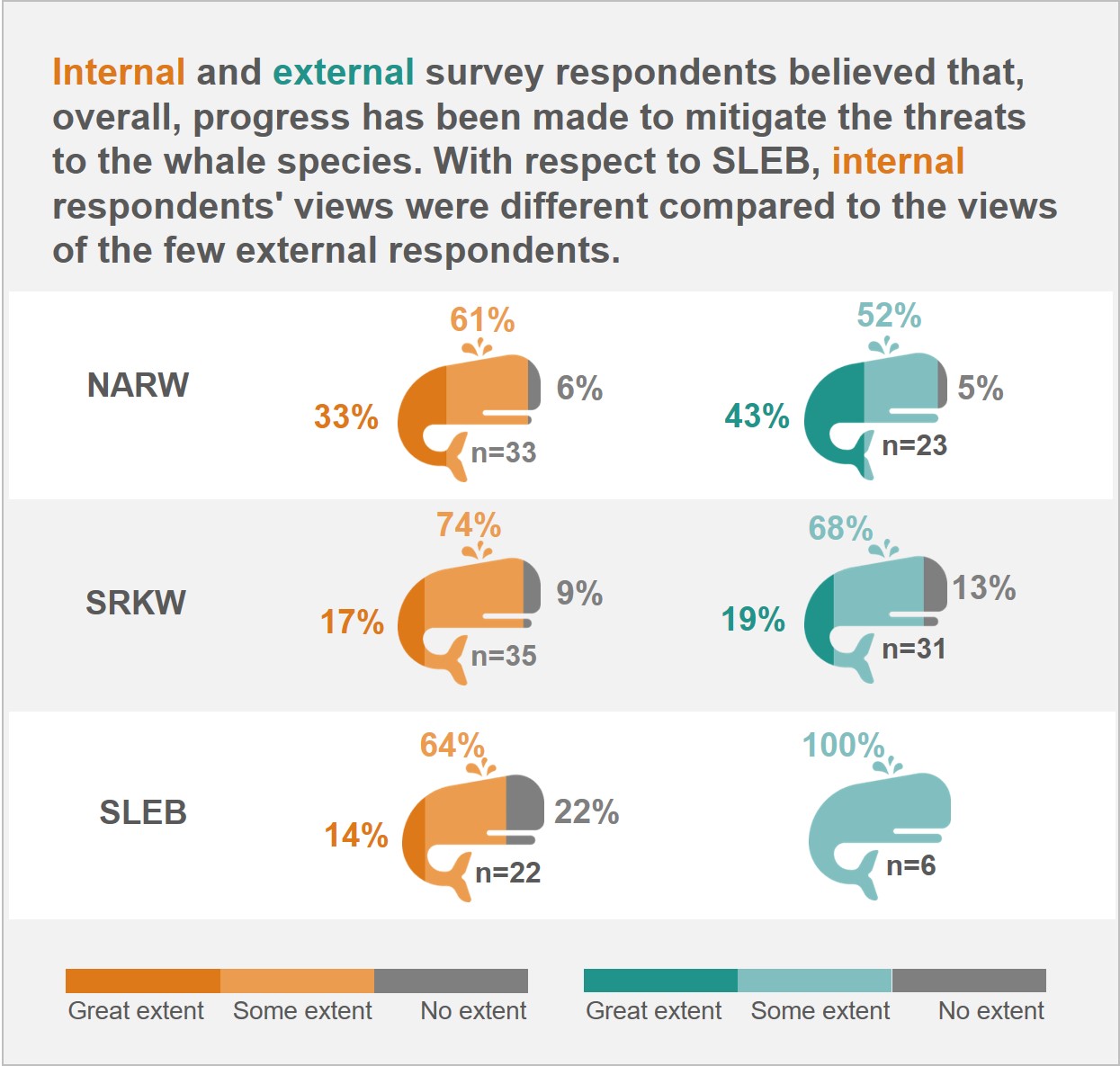

Internal survey respondents believed that less progress has been made with respect to SLEB. This is consistent with other evidence that indicated that funded activities to support SRKW and NARW were prioritized over those for SLEB due to capacity-related issues. External survey respondents provided higher ranking on the progress made with respect SLEB. Likely, this reflects the cumulative efforts from other organizations outside the federal government.

Long description

A visual depicts six whale shaped infographics that indicate that, of 33 internal respondents, 33% believed that overall progress had been made to mitigate the threats to NARW to a great extent, 61% to some extent, and 6% to no extent. Similarly, of 35 internal respondents, 17% believed that overall progress had been made to mitigate the threats to SRKW to a great extent, 74% to some extent, and 9% to no extent. Lastly, of 22 internal respondents, 14% believed that overall progress had been made to mitigate the threats to SLEB to a great extent, 64% to some extent, and 22% to no extent. Of 23 external respondents, 43% believed that overall progress had been made to mitigate the threats to NARW to a great extent, 52% to some extent, and 5% to no extent. Similarly, of 31 external respondents, 19% believed that overall progress had been made to mitigate the threats to SRKW to a great extent, 68% to some extent, and 13% to no extent. Lastly, of 6 external respondents, 100% believed that overall progress had been made to mitigate the threats to SLEB to a great extent.

Other observed progress/benefits

In addition to progress on mitigating threats, several other areas of observed positive changes and progress were identified by internal and external stakeholders.

Ability to make more targeted and flexible mitigation management decisions

- Measures such as area-based closures, fisheries closures, vessel slowdowns, and gear modifications were more specific and targeted as a result of the active and extensive monitoring activities.

- Better knowledge of the whales’ distribution and preferred habitats allowed for site-specific management measures, both for fisheries closures and vessel slowdown measures.

- More and better whale detection monitoring (including the near real-time monitoring) and data informed and supported dynamic protective measures, even in areas that were not within historically known whale habitats.

- Adaptive approaches to management and risk mitigation measures provided the opportunity to increase their effectiveness each year.

Increased public awareness and access to data and information

- On the Atlantic coast, vessel owners/operators can subscribe to receive alerts when whales are detected. The number of accounts increased from 21 in 2019-20 to 450 in 2021-22 and the number of whale alerts also increased—from 2,700 in 2019-20 to 10,972 in 2021-22.

- The disturbance of SRKW as a result of whale-watching activities and recreational boaters’ behaviour has decreased in some areas compared to several years ago, which may be a result of increased public awareness of the importance of recovery measures.

Enhancing and advancing research networks and capacity on whales in Canada

- There are more scientists and academics doing research on whales, which means more data and expertise to advance science in Canada, which directly addresses stated objectives of the funded initiatives.

- There are more partnerships and connections with other organizations, such as provincial governments, academics and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which leads to new knowledge and new information.

- There are more partnerships with Indigenous communities and groups to support co-development of management measures and implementation of Indigenous-led marine stewardship and conservation programs.

3.2.7 Areas of further focus for whale protection efforts

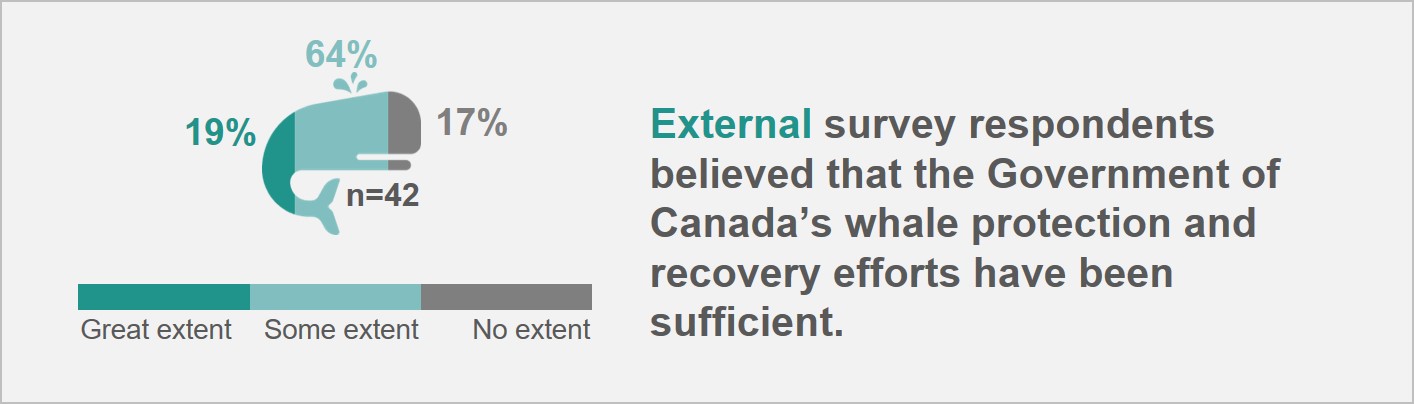

There are clear areas of progress on whale protection and recovery and external experts generally viewed the Government of Canada’s efforts as sufficient. External survey respondents believed that the Government of Canada’s whale protection and recovery efforts have been sufficient.

Long description

A visual depicts a whale shaped infographic that indicates that, of 42 external survey respondents, 19% believed that whale protection and recovery measures have been sufficient to a great extent, 64% to some extent, and 17% to no extent.

Nevertheless, interviewees and survey respondents noted that there is more work to be done. Areas that require more attention in the future are compliance and enforcement, expanding the scope of current activities, and additional partnerships and engagement. Some detail on these areas are provided below.

More authority and capacity for stronger enforcement and control