Elver integrated fisheries management plan (evergreen)

Maritimes Region

Foreword

Anguilla rostrata

The purpose of this Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) is to identify the main objectives and requirements for the Elver fishery in Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Maritimes Region, as well as the management measures that will be used to achieve these objectives. This document also serves to communicate basic information on the fishery and its management to DFO staff, legislated co-management boards and other stakeholders. This IFMP provides a common understanding of the basic "rules" for the sustainable management of the fisheries resource.

Through IFMPs, DFO intends to implement an Ecosystem Approach to Management (EAM) across all marine fisheries. The approach considers impacts extending beyond those affecting the target species and, in this respect, is consistent with the Food and Agriculture Organization’s Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Implementation will take place in a step by step, evolutionary way, building on existing management processes. Advances will be made incrementally, beginning with the highest priorities and issues that offer the greatest scope for progress. A summary of the regional EAM framework is included as Appendix 1 to the IFMP.

This IFMP is not a legally binding instrument which can form the basis of a legal challenge. The IFMP can be modified at any time and does not fetter the Minister's discretionary powers set out in the Fisheries Act. The Minister can, for reasons of conservation or for any other valid reasons, modify any provision of the IFMP in accordance with the powers granted pursuant to the Fisheries Act.

Where DFO is responsible for implementing obligations under land claims agreements, the IFMP will be implemented in a manner consistent with these obligations. In the event that an IFMP is inconsistent with obligations under land claims agreements, the provisions of the land claims agreements will prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.

Signed: Regional Director, Fisheries Management, Maritimes Region

Table of Contents

1. Overview of the Fishery

- 1.1. History:

- 1.2. Type of Fishery:

- 1.3. Participants:

- 1.4. Location of the Fishery

- 1.5. Fishery Characteristics:

- 1.5.1. Gear Type

- 1.5.2. Quota Management

- 1.5.3. Input Controls

- 1.5.4. Dockside Monitoring and Reporting Requirements

- 1.5.5. Timeframe

- 1.6. Governance:

- 1.7. Approval Process:

3. Socio-economic Profile of the Elver Fishery in the Maritimes Region

- 3.1. Quota and Landed Weight:

- 3.2. Average Price:

- 3.3. Landed Value:

- 3.4. Average Landed Value per Licence Synopsis:

- 3.5. Global Supply Context:

- 3.6. Canadian Exports:

4. Management Issues

- 4.1. Managing Fishing Mortality – Quota Setting and Input Controls:

- 4.2. Ensuring Adequate Escapement Across Multiple Life History Stages:

- 4.3. Supporting Recovery of American Eels:

- 4.4. Potential for Spread of the Eel Swim Bladder Parasite, A. crassus:

- 4.5. Potential for Localized Overexploitation:

- 4.6. Depleted Species Concerns:

- 4.7. Gear Impact on Biodiversity and Habitat:

- 4.8. River Changes and Flexibility:

- 4.9. Quota Transferability:

- 4.10. Traceability:

- 4.11. Data Collection and Data Quality:

- 4.12. International Issues - Trade:

5. Objectives

6. Strategies and Tactics

- 6.1. Productivity

- 6.2. Biodiversity

- 6.3. Habitat

- 6.4. Culture and Sustenance

- 6.5. Prosperity

10. Monitoring and Evaluation:

- 10.1. Monitoring

- 10.2. Evaluation

12. Glossary:

13. References:

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Summary of Maritimes Region EAM Framework

- Appendix 2: Summary Table – DFO Maritimes Region EAM Framework Applied to the Elver Fishery

- Appendix 3: Elver Advisory Committee Terms of Reference (1998)

- Appendix 4: Dockside Monitoring and Reporting Requirements for the Elver Fishery in 2017

- Appendix 5: Policies and Procedures for Changing Elver Fishing Locations

- Appendix 6: Conservation & Protection Statistical Summary for 2011-2013

List of tables

List of figures

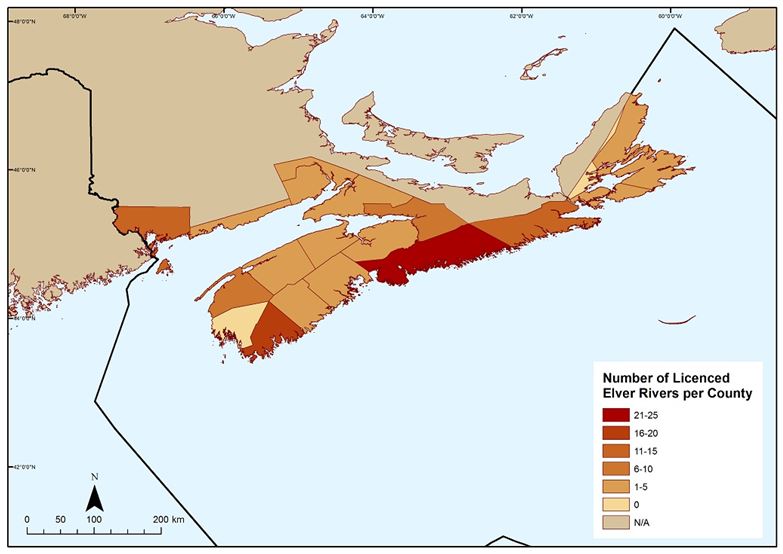

- Figure 1- Number of licensed elver rivers by county in the Maritimes Region, in 2014

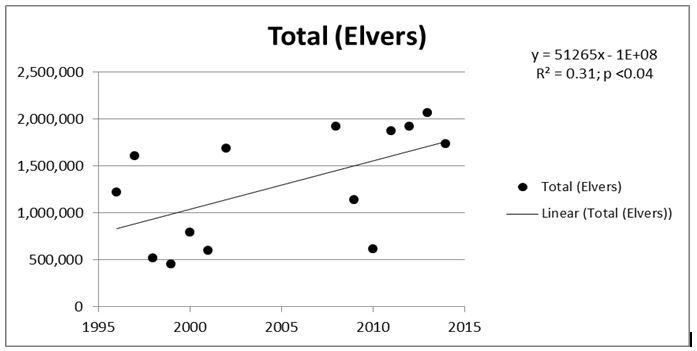

- Figure 2- Estimated annual number of elvers returning to the East River Chester

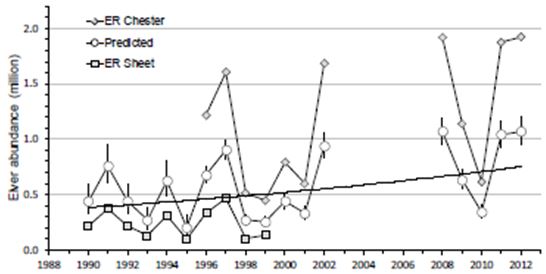

- Figure 3- Estimated annual elver run size to East River-Sheet Harbour (1990-1999) and East River-Chester (1996-2002 and 2008-2012)

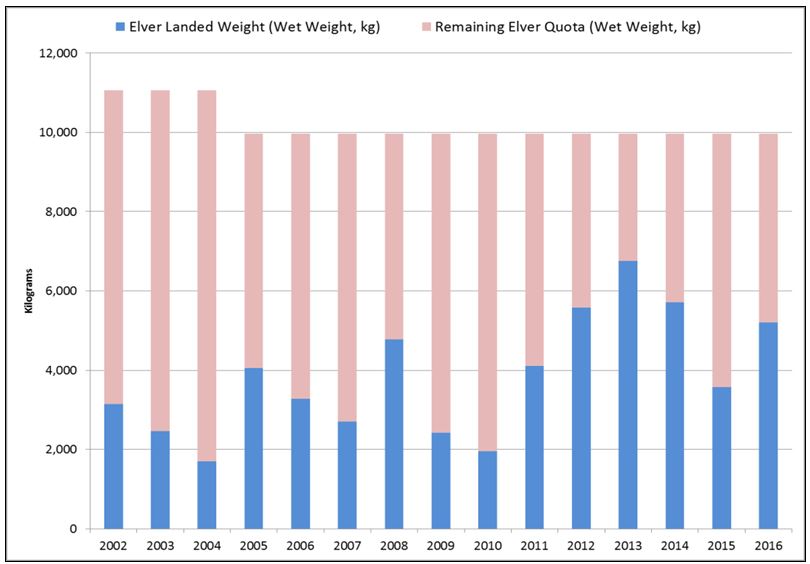

- Figure 4- Maritimes Region Elver Quota and Landed Weight (kg, wet weight), 2002-2016(p)

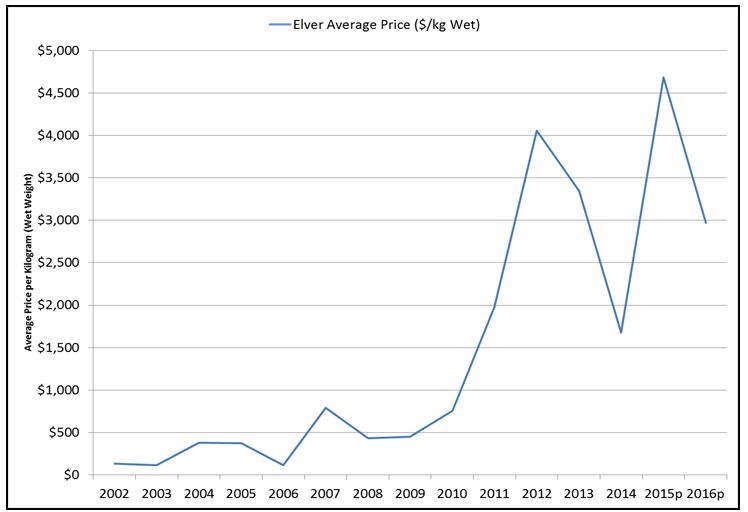

- Figure 5- Maritimes Region Elver Average Price ($/kg, wet weight), 2002-2016(p)

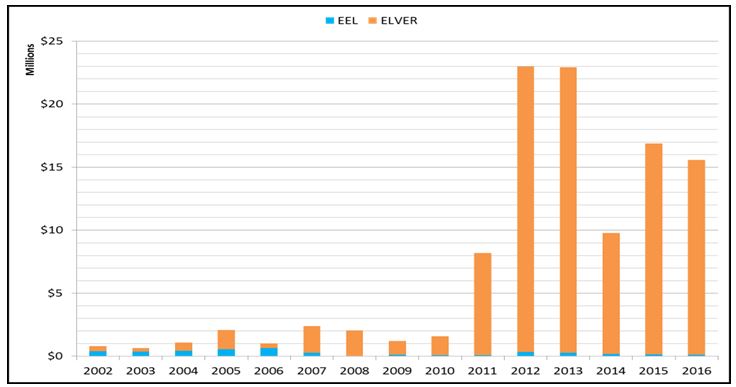

- Figure 6- Maritimes Region Elver and Eel Landed Value, 2002-2016(p)

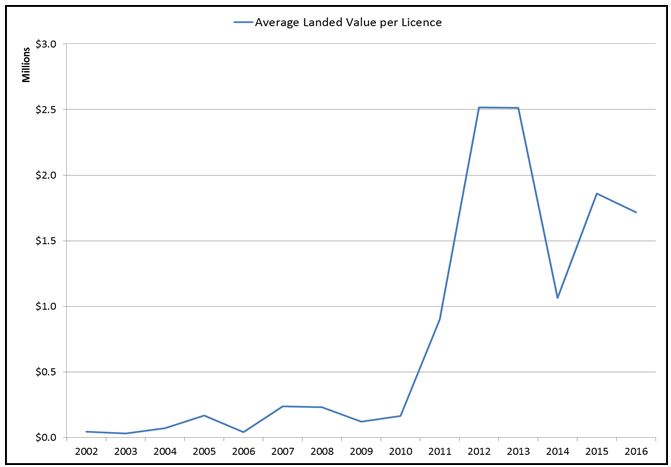

- Figure 7- Maritimes Region Elver Average Landed Value per Licence, 2002-2016(p)

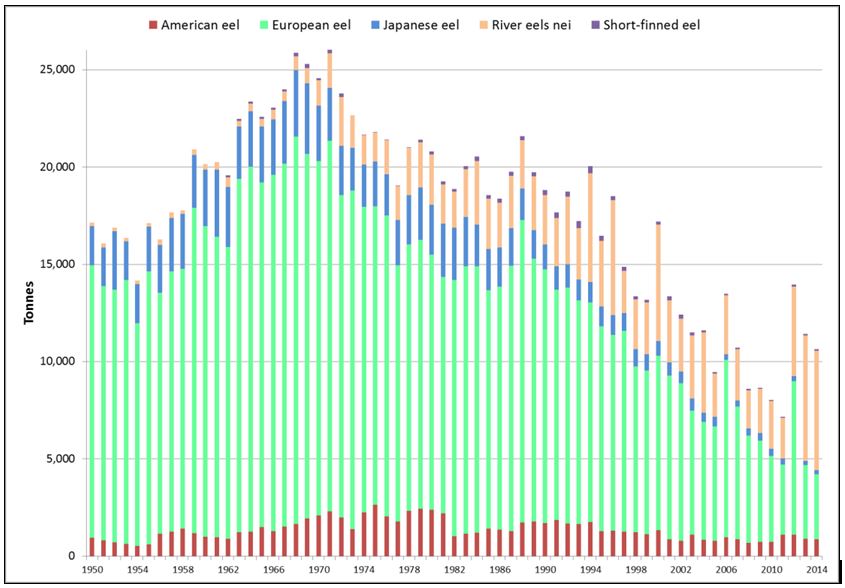

- Figure 8- Global Capture Production of Eels by Species, 1950-2014

- Figure 9- Value of Canadian Exports of Eel/Elver, 2000-2016

1. Overview of the fishery

1.1. History:

Early fishery development and licensing

The Elver fishery in the Maritimes Region dates back to the early 1980s, when a few experimental licences were issued to individuals who expressed an interest in trying to catch elvers, American Eels (Anguilla rostrata) under 10 cm. No elver landings were reported under these licences so they were not renewed in subsequent years. In 1989, two experimental licences were issued to fish elvers which resulted in landings of 26 kg for the year. The fishery developed slowly and total annual landings remained well below one tonne.

By 1994, there were a total of four experimental licences and, for the first time, landings surpassed one tonne and reached 1,574 kg. When landings reached 3,338 kg in 1995, there was a dramatic increase in the demand for licences which prompted Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to move to a public process for the issuance of new licences. Between 1996 and 1997, licences were temporarily capped in the Scotia-Fundy sector (now DFO Maritimes Region; Figure 1) at nine – six permitted direct sale and three permitted harvest for domestic aquaculture purposes. Four of these experimental licences were made permanent in 1997.

In 1998, one experimental licence for aquaculture purposes was not renewed, and approval was given for two new experimental elver licences. One experimental licence was issued to an association of commercial eel fishers in Shelburne County, who agreed to cease adult eel fishing. The other was issued in 1999 to a commercial eel fisher in Richmond County, for domestic aquaculture purposes. This licence was not renewed past 2002.

In 1999 and 2000, the participation requirement for experimental licences was waived due to market conditions, but fishing under these licences took place in all other years. Having established commercial viability, these five experimental licences were converted into permanent licences in July of 2006.

The Elver Advisory Committee was established in 1998, and the first Elver Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) was developed at that time.

Fishery context – American Eel conservation

There has been concern about the conservation status of eels in Canada, particularly in Quebec and Ontario, for many years. In 2003, the International Eel Symposium held in Quebec City resulted in the issuance of the Quebec Declaration of Concern, a call for immediate action to recognize and halt the decline of eel populations worldwide. One of the driving factors in making this Declaration was the sharp decline in recruitment of American Eel to Lake Ontario. In the longest-term Canadian dataset, the abundance of eels returning to the Moses-Saunders dam on the upper St. Lawrence River in the early 2000s was only 2% of the average returns in the 1980s (Casselman 2003). Other datasets from Quebec and Ontario similarly indicated large declines over this time period (Richkus and Whalen 2000).

In September 2004, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, in concert with the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario, called for a 50% reduction in eel mortalities resulting from fishing, habitat loss and hydro dams, and each DFO Region was asked to develop management approaches to address reductions in eel mortalities. In the Maritimes Region, management measures implemented included:

- Increase in the minimum size limit for adult eels to 35 cm (from 20 cm in Nova Scotia and from 30 cm in Southwest New Brunswick);

- Licence conditions were also modified to establish mandatory escape mechanisms, in either the eel fishing gear or live holding boxes, to permit the escape of small eels. More recently, DFO has allowed eel licence holders in Southwest and Eastern Nova Scotia management areas to exchange their adult eel licences for green crab licences.

- Individual quotas for the elver fishery were reduced by 10% in 2005, leading to a 10% reduction in the Total Allowable Catch (TAC). Additionally, a provision that had allowed licence holders to apply for a 30% quota increase once their initial quota was caught was removed. As some licence holders had been able to catch their quota plus the additional 30% in years with good elver runs, this amounted to a 40% reduction in their annual catch in those years.

- Since this time, the elver quotas and all effort measures, such as gear type and number, have been frozen in order to respect this directive regarding mortality of eels.

In 2006, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) recommended that the American Eel be listed as Special Concern under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) (COSEWIC 2006). Between 2006 and 2009, an American Eel Management Plan for Canada was drafted by DFO and the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario. While this national management plan was never formally adopted, some management actions recommended under the plan were implemented in different jurisdictions. DFO and provincial authorities have reported on progress towards the goals of the draft Plan, most importantly the short-term goal of a 50% reduction in mortality relative to the average mortality in 1997-2002 (DFO 2010; Mathers and Pratt 2011). The long-term management goal stated in the draft Plan was to rebuild overall abundance of American Eel in Canada to its level in the mid-1980s. Eels were also listed as endangered under the Ontario Endangered Species Act in 2007 and as vulnerable under the Newfoundland and Labrador Endangered Species Act in 2011.

COSEWIC reassessed the species in 2012 and recommended that American Eel be listed as Threatened under SARA (COSEWIC 2012). COSEWIC recognized that trends in status indicators are highly variable, with trends in the upper St. Lawrence estuary continuing to indicate very low recruitment, but indicators in Atlantic Canada mainly unchanged or showing some increase in abundance. A DFO Recovery Potential Assessment (RPA) was held in 2013 and concluded that trends in abundance indices supported COSEWIC’s conclusion that there has been a significant decline in American Eel abundance, with declines having been most severe in the St. Lawrence Basin and specifically Lake Ontario (DFO 2014).

In response to the 2012 COSEWIC assessment, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans is required to make a recommendation on whether or not to list the American Eel as Threatened under SARA. Public consultations on the expected social and economic consequences of listing began in November 2015 and concluded in 2016. A decision by the Government of Canada will be made based on the available scientific information, the outcomes of consultations, and an analysis of the socioeconomic impacts associated with listing and not listing the species. A decision on whether or not to list had not yet been made as of the writing of this IFMP.

Conservation Stocking

In 2005, provisions were put in place that allowed elver licence holders to catch up to an additional 10% of their quota if elvers caught went to restocking initiatives in Canadian waters. From 2006 to 2010, a total of four million elvers were sold by DFO Maritimes Region elver licence holders to Ontario and stocked into waters of the upper St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario (Mathers and Pratt 2011). Stocked eels were found to survive well and disperse in the watershed, but they were also found to mature at a smaller size and younger age than natural populations in the upper St. Lawrence River, with a lower proportion of stocked eels maturing as females. After 2010, the program was stopped due to concerns about transferring the swim bladder parasite Anguillicoloides crassus from the Maritimes Region to Ontario.

1.2. Type of Fishery:

The elver fishery in the DFO Maritimes Region is a limited entry fishery with commercial and communal commercial licences. As defined in the Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations (MPFRs), elvers are American Eels less than 10 cm in length, often known as “glass eels” in other jurisdictions. Harvesting is carried out from shore or in-river without the use of vessels in most cases. It is a single species fishery with a limited number of participants who are licensed for specific rivers.

To date, the elver fishery has been managed under an “enterprise allocation” modelFootnote 1, in which each licence holder has an individual quota. Under this management system, the fishery is also exempt from the owner-operator policy laid out in Commercial Fisheries Licensing Policy for Eastern Canada – 1996, and licences may be held in company names. The licences are also permitted to be fished by a limited number of employees, as long as those employees hold Personal Fishing Registrations with DFO, and are named in the conditions of licence.

1.3. Participants:

There are nine licences in the elver fishery: eight commercial licences and one communal commercial licence. Each licence holder can engage people to fish under their licence up to a maximum number, ranging from eight to twenty-eight fishers depending on the licence. In 2017, a total of 175 participants were authorized to fish under the nine licences. One elver licence is collectively owned by seventeen former large eel fishers but the rest are owned by an individual, company, or First Nation. Individual allocations are provided in Section 7.2.

1.4. Location of the Fishery:

Elver fishing takes place at or near the head of tide at the mouth of rivers. Fishing is typically permitted in tidal waters or up to 1000 m upstream of the tidal water boundary (as defined in the MPFRs), although fishing somewhat further inland may be approved on a case by case basis. The current elver fishery occurs in Southwest New Brunswick, the Upper Bay of Fundy, Southwest Nova Scotia, along the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia, and in portions of Cape Breton Island (Figure 1).

Each licence holder is limited to fishing within a set of specified waterbodies (rivers and streams), which are unique to that licence holder. Traditionally, each licence holder had a “territory”, a roughly contiguous area in which they had exclusive access, though not necessarily to all the rivers in that area. For example, a licence holder might have the only access to fish elvers in a given county. More recently, a few licence holders have broken their holdings over several parts of the Region, but most have held the same territories for many years. As it can take several years to learn how to fish a particular river system most effectively, the change in fishing locations over time is typically limited.

1.5. Fishery Characteristics:

1.5.1. Gear Type

All gears used are relatively small, fixed gears, set or operated by hand (Table 1). Traditionally, the majority of the catch was with dip nets, and a significant proportion of the elvers (>30%) have been caught that way in recent years. Pots and traps are required to be fitted with screens to exclude larger animals.

The bycatch in the fishery is generally low and mainly consists of small invertebrates (like amphipods), although there is some potential for other juvenile fish to enter the gear. All other species and any juvenile eels over 10cm are required to be returned to the water in the manner that causes the least harm. As the gear is designed and fished in order to keep the elvers alive, it is expected that any juvenile fish or other animals caught as bycatch can typically be released alive and unharmed.

| Gear Type | Total Number | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dip Nets | 176 (52 can be used with stationary wings) |

Length of stationary wings varies and is specified in licence conditions. |

| Elver Traps | 140 | Elver traps are considered “eel traps” under the MPFRs. Maximum size limits for elver traps vary and are specified in licence conditions. |

| Elver Pots | 80 | Elver pots are considered “eel pots” under the MPFRs. |

| Push Trawls | 3 | Size restriction is in licence conditions. Maximum size is 2.2m in width, and 1.3m in height. |

| Pipe Traps | 6 | Size restriction is in licence conditions. |

Required distances between fishing gears are set in the licence conditions, which generally require elver traps be set at least 30.5 m apart. On a case-by-case basis, DFO has authorized the placement of elver traps as close as 20 m apart on specific river systems, as long as the Fisheries Act requirements for fish passage are met. This is generally approved only to allow the use of two elver traps in a system that would otherwise only hold one.

1.5.2. Quota Management

Each licence specifies a non-transferable individual quota that can be harvested, and caps on the amount that can be taken from any individual river. Individual quotas of 1,000 kg dry weight per licence holder were initially set in 1989, based on scientific information that was available at the time (summarized in Jessop 1995, Jessop 1996). In 2005, individual quotas were reduced by 10% across the board, as a conservation measure. Additionally, as of the 2015 fishing season, the fishery transitioned to expressing quotas and landings in wet weights rather than dry weights (dry weight is established to be 75% of the wet weight of elvers). Currently individual quotas are 1,200 kg wet weight (900 kg dry weight) for most licence holders, and 360 kg wet weight (270 kg dry weight) for one licence holder, for a TAC of 9.96t wet weight (Table 4).

1.5.3. Input Controls

Limited information on American Eel abundance and dynamics in the Maritimes Region has made it difficult for DFO Science to provide specific advice about quotas, so input controls have been used to keep fishing mortality moderate. These input controls include the gear type, size, and number, the waterbodies in which fishing is permitted, fishing locations within waterbodies, the number of persons permitted to fish under a licence, and the fishing season, and are specified in licence conditions. As the fishery was developing, variation among licences was permitted in order to allow licence holders to develop gear configurations that were efficient in specific river systems, while limiting effort and exploitation.

1.5.4. Dockside Monitoring and Reporting Requirements

Dockside monitoring and reporting requirements for the elver fishery are detailed in Appendix 4. Requirements include daily hail-outs and hail-ins, and the use of daily logbooks which include the identification of catch, transport information, SARA species interactions, a running total of all elvers being held in designated holding facilities, and sales information. Each elver licence holder is required to have three (3) monitored offloads per year (e.g. a dockside monitor would be there to monitor the elvers as they are being brought into the holding facility from the rivers and weighed). Additionally, each time elvers are sold from the holding facility, the weight of elvers shipped must be monitored and verified by a dockside monitor.

1.5.5. Timeframe

Elvers typically arrive in Scotia-Fundy waters in late March and early April, with the peak run usually in May. They appear first in Southern areas of Nova Scotia and the Bay of Fundy and later along the Eastern Shore and in Cape Breton, where the fishery may extend well into June or even July.

1.6. Governance:

DFO oversees Canada’s scientific, ecological, social and economic interests in oceans and fresh waters. That responsibility is guided by the Fisheries Act, which confers responsibility to the Minister for the management of fisheries, habitat and aquaculture and the Oceans Act (1996), which charges the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada with leading oceans management. The Department is also one of three responsible authorities under the Species at Risk Act (2002). All three Acts contain provisions relevant to fisheries management and conservation. However, the Fisheries Act is the Act from which the principal set of regulations affecting the licensing and management of fisheries flow. For the Maritimes Region, these include the Fishery (General) Regulations (FGRs), the Atlantic Fishery Regulations 1985 (AFRs) and the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations (ACFLRs). Eel fishing in the Maritimes Region is also managed subject to the Maritime Provinces Fishery Regulations (MPFRs). The MPFRs establish close times, gear restrictions, and size limits for eel fisheries in the Maritime Provinces, including the elver fishery.

The management of commercial fisheries is governed by a suite of policies related to the granting of access, economic prosperity, resource conservation and traditional Aboriginal use. Information on these can be found on the DFO website at: /reports-rapports/regs/policies-politiques-eng.htm. Notable policies include the Commercial Fisheries Licensing Policy for Eastern Canada, the New and Emerging Fisheries Policy and the Sustainable Fisheries Framework.

This management plan has been developed according to a framework for an ecosystem approach to management (EAM), developed by DFO in the Maritimes Region (Appendix 1). The framework requires that fisheries management decisions reflect the impact of the fishery not only on the target species but also on non-target species, habitats and the ecosystems of which these species are a part. Additional information on the framework as it directly applies to the elver fishery is included in Appendix 2 of this plan.

The main advisory body is the Elver Advisory Committee, which was struck on February 20, 1998. The committee is chaired by the Senior Advisor responsible for the eel and elver fisheries in the Maritimes Region, and the Terms of Reference and the membership list for the Committee can be found in Appendix 3.

The Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS), through the Regional Advisory Process (RAP), provides science advice on the status of the stocks. Industry participates in the peer review meeting of the stock advice. The stock status advice in the form of a Stock Advisory Report (SAR) and /or a Research Document or a Science Response is a primary input for the consultations on management of the fishery at the advisory committee. Research Documents, SARs or Science Response documents are available from the DFO CSAS website: /csas-sccs/index-eng.htm.

1.7. Approval Process:

The Elver Advisory Committee is the main consultative body for the fishery, and recommendations and advice to DFO on the management of the elver fishery are provided through the Advisory Committee. While operational decisions are made within the Maritimes Region Fisheries Management Branch, decision-making on complex issues related to access and allocations, changes to licensing policy, or issues related to international agreements will be elevated to the Regional Director-General or the Minister.

Evergreen IFMPs are developed by DFO in consultation with the fishing industry, provincial and territorial governments, First Nations and Indigenous groups, advisory bodies and other interested stakeholders and partners. Generally, significant revisions to the IFMP should be provided in writing prior to advisory committee meetings so that Indigenous and industry representatives have a reasonable time to respond. Approval of the IFMP is at the level of Regional Director of Fisheries Management for the Maritimes Region.

2. Stock Assessment, Science and Traditional Knowledge

Jessop (1995) and Jessop (1996) summarize the information gathered about elvers in Nova Scotia and the elver fisheries up to 1996, and collectively formed the science advice on which the fishery was established. The general status of American Eels in the DFO Maritimes Region was updated to the year 2010 and the analysis and advice was published as Bradford (2013). COSEWIC assessed the status of the American Eel in Canada in 2012, and recommended that the status be changed to Threatened (COSEWIC 2012). As a result, an RPA for eels in Eastern Canada was held by DFO in June, 2013. The working papers and Science Advisory Report (DFO 2014) from the RPA are important and recent sources of information on the status of eels and elvers in the Maritimes Region.

2.1. Biological Synopsis:

The life history of the American Eel is summarized in Bradford (2013):

The American Eel is widely distributed within the western North Atlantic Ocean with records of occurrence extending from southwestern Greenland, along the coast of North America from southern Labrador to the Gulf of Mexico, Panama, and the West Indies (Scott and Scott 1988). Mature eels spawn in the area of the Sargasso Sea during late winter and spring (McCleave et al. 1987). Larval eels (leptocephali) drift and swim in the upper 300 m of ocean while currents, particularly the Gulf Stream, distribute them along the Atlantic coast of North America. Upon metamorphosis, glass eels move coastward. Glass eels begin to ascend streams of the Maritimes Provinces about late March or early April, becoming elvers and increasingly pigmented as the run progresses upstream. Young eels continue, for perhaps years, to distribute themselves throughout the available habitats. After a variable period of time, ranging perhaps from five to twenty or more years in Atlantic Canada, juvenile (yellow) eels begin sexual maturation, become silver eels, and migrate to sea during late summer and autumn. Maturation is completed at sea. Spawning occurs in the Sargasso Sea. Adults die after spawning.

American Eels of various life stages occupy a wide variety of habitats - the ocean, estuaries, streams, rivers, and lakes. Their extensive geographic range, ability to occupy a wide variety of habitats, and a panmictic (intermixing of eels from all geographic areas) breeding population (Avise et al. 1986) evidences and contributes to their adaptive plasticity. Growth rates of yellow eels are variable, depending upon the latitude (slower growth in northern areas) and nature (productivity) of the habitat. Within a given habitat, growth rates of individual eels vary greatly. The sex ratio of resident eel populations becomes more skewed towards females with increasing latitude. Females are older and larger at sexual maturity than males in northern areas (Helfman et al. 1984; Jessop 1987). The proportion of female eel is positively correlated with lacustrine habitat area within Maritimes Region rivers (Jessop 1987).

The migration of juvenile eels into freshwater is described in DFO 2014:

Glass eels initially enter freshwater beginning in late winter. At this point they begin feeding, become increasingly pigmented and are called elvers. In Canada, they enter rivers between late April and early AugustFootnote 2, with the majority of ingress occurring earlier in rivers closer to the spawning area. Environmental predictors of glass eel runs are variable, but increased temperature and reduced flow (corresponding to lower water velocity) in rivers early in the upstream migration season may trigger upstream movement. Eels are initially believed to be attracted to freshwater via chemosensory cues.

Eels begin moving upstream when stream water temperatures reach 10˚C and continue until temperatures exceed 20˚C, with peak migration occurring at temperatures between these extremes. Water temperatures lower than 10˚C can result in a pause in migratory behaviour until temperatures increase again. Other than stimulating migration into freshwater, temperature and water flow do not seem important to eel movement. Elvers that enter freshwater may spend much of this life stage migrating upstream. Eels swim upstream using burst-swimming through the hydraulic boundary layer and water column, in between periods of rest in the substrate. In current velocities exceeding 25-35 cm/s, elvers have difficulty swimming and maintaining their position and spend more time in protective substrates.

With respect to habitat availability in the DFO Maritimes Region, Pratt et al. (2014) point out that electrofishing surveys for salmonids on the Saint John River demonstrate that eels are widely distributed in the river basin below the Mactaquac Dam, but virtually absent from the 46% of the river basin upstream from the Dam. The Saint John River system is by far the largest river system in the Maritimes Region. Many other dams in the Maritimes Region are believed to block upstream passage of American Eels, though the extent of habitat loss has never been directly assessed for Eels. Elver licence holders have noted that many of the systems currently fished for elvers contain dams with no fish passage. Anecdotally, a high percentage of the elver catch in the fishery is taken just below dams and other barriers to fish passage.

2.2. Ecosystem Interactions:

The COSEWIC (2012) Assessment and Status Report notes “The American Eel is a major predatory fish in freshwaters and in marine systems and is probably an important prey species. Consequently, the American Eel likely plays an important ecological role in a variety of aquatic communities (e.g. Smith and Saunders, 1955; O’Connor and Power 1973).” Glass eels and elvers are known to be eaten by many other species, though very little published information on the role of this life history stage in estuarine and freshwater systems was found. While elvers are generally thought of as prey rather than predators, Dutil et al. (1989) found that elvers began feeding soon after they entered estuaries and streams, mainly on insect larvae.

Implications of known ecosystem changes for American Eels are summarized in Chaput et al. (2014a). In the DFO Maritimes Region, they particularly flag the threat posed by the introduction of Smallmouthed Bass and Chain Pickerel both as predators directly on eels and for their impacts on the prey communities eels rely on.

Climate Change

A consideration of the potential impacts of climate change on eels can also be found in Chaput et al. (2014a). The impact of climate factors on population dynamics of American Eels is complex, but the implications for the elver fishery will be felt through potential changes in elver abundance, distribution, or perhaps size. In that respect, understanding the driving factors behind these changes is less important to managing the fishery than having a monitoring and assessment framework in place that would allow DFO to detect and respond to changes to meet objectives for productivity and biodiversity. Section 11 (Plan Enhancement) describes priority items for improving our monitoring and assessment framework for the fishery.

2.3. Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge / Traditional Ecological Knowledge:

There are several recent resources that describe the significance of eels to the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Peskotomuhkatiq peoples of Atlantic Canada. The COSEWIC (2012) Assessment and Status Report provides a short list of references regarding the historical and contemporary significance of American Eels to Aboriginal peoples. Mi’kma’ki All Points Services (MAPS) released a report in 2011 summarizing results of interviews with elders and eel fishers, and including a more comprehensive bibliography of resources related to traditional Mi’kmaq knowledge about and uses of eels (MAP 2011). The Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources (UINR) also released a series of ten short videos on eels and their importance to the Mi’kmaq people in 2013 (www.uinr.ca), and a report entitled Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge: Bras d’Or Lakes Eels in 2012 (Denny et al. 2012).

The COSEWIC (2012) Assessment and Status Report integrates Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK) into many sections of the report, including information about eel behavior and morphology as well as stock status. With respect to stock status, ATK about eels suggests that eel populations have declined and that large eels are less available to fisheries than they were in the past (Davis et al. 2004, MAP 2011, Denny et al. 2012, COSEWIC 2012). Dams are commonly cited as a contributing factor to these declines (summarized in COSEWIC 2012). In interviews, elders of Paq’tnkek First Nation in Antigonish County, Nova Scotia, cited local overfishing in the 1990s and loss of access to eel fishing grounds as contributing to the decline in eel fishing in the Paq’tnkek area (Davis et al. 2004).

In Cape Breton, workshops with elders held in 2004 and 2006 also indicated that eel populations had declined in the Bras d’Or Lakes (CEPI 2004, 2006). Reasons cited included physical habitat changes resulting from bridges and the Canso Causeway, and the reduction in eelgrass beds (partially due to invasive green crabs and tunicates) (CEPI 2006). In 2004, workshop participants also expressed concern about the ability of eel populations in Bras d’Or Lakes to sustain commercial harvesting (CEPI 2004). The UINR report from 2012 echoes a number of these ideas, but elders, eel fishers, and other knowledge holders also expressed concern about the swim bladder parasite A. crassus (Denny et al. 2012). Biologists from UINR have worked with eel fishers in the Bras d’Or Lakes to study the prevalence of this parasite over time and in different parts of the Bras d’Or Lakes system. A range of habitat changes in the Bras d’Or Lakes are noted as threats to eels, including contamination from sewage and industrial sources and sedimentation. The study notes that there is currently no Food, Social and Ceremonial (FSC) fishing of the elver stage of eels (Denny et al. 2012).

Concerns were raised in Denny et al. (2012) and MAP (2011) about the potential effect of the elver fishery in the Region on eel populations, the availability of eels for FSC fishing, and the availability of elvers as prey for other species, including adult eels. Representatives of the Maritime Aboriginal Peoples Council have also expressed concerns to DFO in the past about the potential impact of elver fishing on eel populations (Roger Hunka, personal communication).

2.4. Stock Assessment and Stock Scenarios:

American Eel abundance, status, and trends in Canada

The RPA considered all available information on stock status, distribution, and trends for American Eels in Canada (DFO 2014). Research documents prepared to support the RPA process included: population dynamics models and assessment of population sensitivity to perturbation (Young and Koops 2014), identification of the functional habitat of American Eels in Canada (Pratt et al. 2014), description and evaluation of threats (Chaput et al. 2014a) and mitigation options to address principle threats (Chaput et al. 2014b). The Science Advisory Report (DFO 2014) concluded that: “Trends in indices support the conclusion from COSEWIC that there has been a decline in American Eel abundance over the past 32 years with declines having been most severe in the St. Lawrence Basin and specifically Lake Ontario. Some indicators show recent (16-year) upturns in abundance, which have yet to manifest themselves as improvements in standing stock indices.” The RPA also considered progress towards the short and medium-term targets laid out in the draft national American Eel Management Plan (CEWG 2009). The short term abundance target of arresting decline and showing increases in indices was found to have been achieved for the recruitment life stage (i.e. glass eels and elvers) but not for other life history stages (DFO 2014). The medium-term abundance target is to rebuild abundance in all regions and overall in Canada to the levels of the mid-1980’s, as measured by the key available abundance indices. Overall for Canada, the medium term recovery targets for have not been attained for any life stages (DFO 2014).

In the RPA, the elver and large eel fisheries in the Maritimes Region were considered a “medium” threat, as were loss of habitat, fragmentation of habitat, turbine mortality, silt and sediment, the swim bladder parasite A. crassus, changes in prey communities, changes in predator communities, and non-native species invasions (DFO 2014).

American Eel Stock Assessment in DFO Maritimes Region

Bradford (2013) summarizes the fishery-dependent and independent data available for assessing American Eel abundance and trends in the DFO Maritimes Region. Reported landings of large eels are not considered to provide a complete picture of either fishing activities or general status of eels in the Region.

Since the 1950s, reported annual catches of American Eels in the commercial fishery have varied between 11 t and 230 t. Reported catches of American Eels in 2012 and 2013 were 46 t and 55 t, respectively. The amount of gear licensed to fishers reporting landings explained approximately 90% of the interannual variability in reported landings between 1993 and 2004 (Bradford 2013), suggesting that catch rates generally reflected effort rather than abundance. Estimates of potential effort (number of gear units) for individual fishers reporting catches were not considered to be sufficiently accurate to allow for use of catch per unit effort as an index of abundance. No reporting is required from the recreational eel fishery, and consequently no information on effort or landings is available.

Fishery independent data sources on yellow and silver eels include electrofishing surveys on index rivers (the Nashwaak and Big Salmon Rivers in New Brunswick and the LaHave and St. Mary’s Rivers in Nova Scotia). These electrofishing surveys are generally designed for salmonids, but have been used in stock assessment and in the recent COSEWIC and RPA processes. The composite electrofishing data for yellow and silver eels in the St. Mary’s, Big Salmon, and Nashwaak Rivers was found to show a statistically significant decline of 3% annually (Bayesian C.I. -3.2% to -2.9%) from 1985-2012, or -39% overall since 1996 (DFO 2014).

Elver Stock Assessment – data sources

In the elver fishery, detailed daily reporting of location, effort (hours fished and number of gear) and catch by gear-type has been a condition of licence since the inception of the fishery. Reporting of the data is currently restricted to aggregate summaries of catch and effort, owing to prohibitions under the Privacy Act.

Elver run sizes to Nova Scotia rivers have been estimated at two locations, East River-Sheet Harbour during the years 1989-1999, and East River-Chester during the years 1996-2002 and 2008-present (Bradford 2013). At East River-Chester, four Irish-style elver traps are operated at the mouth of the river, downstream of a physical barrier to upstream passage, and at or just upstream of the head of tide. The traps are operated from late April to mid-July in most years and are thought to intercept the great majority of elvers that escape the commercial fishery, which occurs several tens of meters downstream in most years. Elvers may continue to move through the sites into late September but at low numbers after late August.

Elver catches in the traps are counted at least daily for each trap until late June when elver run size declines and counts are every second day. Individual elvers are counted when numbers are low (less than about 150 elvers) and volumetric estimation with graduated cylinders is used when catches are high. Estimates using the graduated cylinder are calibrated three times per week to account for the known decline in elver size during the run. Procedures for estimating the daily and seasonal total elver catch at 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the seasonal total catch from 1996-2000 were described in Jessop (2000). Elvers not sampled for biological data are returned alive to the wild above the barrier.

Total run size for the East River-Chester is calculated as the sum of the commercial catch, which is converted from kilograms to number of elvers, plus the estimated escapement (i.e. the catch in the elver traps).

Elver Stock Assessment – results

Considering the results of elver monitoring at East River-Chester from 1996 to 2010, estimates of total run size ranged from approximately 450,000 elvers in 1999 to approximately 1.9 million elvers in 2008, and were found to vary interannually without trend (Figure 2). The average run size for 1996-2010 was 1,054,606 ±538,398 elvers (Bradford 2013).

An increasing trend in annual run size has been observed in recent years, with run sizes for 2011 to 2014 representing four of the five largest runs since monitoring began in 1996 (Figure 2). A composite elver index including all data from East River-Sheet Harbour and East River-Chester (1990-2012) was included in the RPA and was found to show no significant trend over the entire time series or the last 16 years (DFO 2014; Figure 3). Addition of the East River Chester data up to 2014 does show a statistically significant, increasing trend.

“Predicted” values are the composite elver recruitment index for the Maritimes Region from the 2014 RPA (DFO 2014).

Considering the data from 1996 to 2007, the total catch was found to have varied between 478 kg in 1999 and 4,000 kg in 1997, with no discernible trend (Bradford 2013). Commercial catch exhibited a positive correlation with effort expressed as either Total Number of River visits or Total Hours Fished.

Reduced catches during 1999 and 2000 corresponded to years of low prices for elvers, but there was no significant correlation between total annual catch and elver price. Total effort was weakly correlated with elver price. Since the analysis by Bradford, elver landings have continued to vary considerably, with catches exceeding 4,000 kg in 2012 and 5,000 kg in 2013 (Figure 4), corresponding with an unprecedented peak in elver prices (Figure 5).

As part of the RPA, Young and Koops (2014) modeled population dynamics of eels in Eastern Canada, to assess population sensitivity to perturbation, and to compare possible dynamics of American Eel under various hypotheses regarding the distribution of eel larvae. While assessing the population sensitivity, they modeled the impacts of fisheries and turbine mortality on silver eel abundance. They concluded that “Elver fisheries in [Maritimes Region] (at the instantaneous mortality rate of 0.05) had very little effect on the population overall (comparing scenarios A and B: < 1% change in overall abundance, < 0.1% change in λ), and only slightly more on the individual zone (< 2% change in SF abundance), regardless of larval distribution [assumptions].” That is, they found that the elver fishery, as modelled, led to less than a 2% reduction in the abundance of silver eels in the Maritimes Region, over 50 years.

The modeling indicated that “Silver and yellow eel fisheries occurring in the four RPA zones had the largest effects on modeled growth rates in abundance whereas elver fisheries in the DFO Maritimes Region, as modelled, had very little effect on the changes in abundance overall (DFO 2014).” It should be noted that these conclusions are under the assumption of an instantaneous mortality rate of 0.05 from elver fishing (i.e. F=0.05), which was considered an “approximation of current levels” but is not based on any quantitative assessment of fishing mortality in the elver fishery in the Maritimes Region (Young and Koops 2014).

2.5. Precautionary Approach (PA):

As described in Section 11, the development of Precautionary Approach reference points for this fishery and for American Eel fisheries at all life history stages is a Regional goal.

2.6. Research:

The continuation of the East River-Chester elver index described above is the highest-priority research activity related to eels and elvers in the DFO Maritimes Region. In 2009, a survey of yellow and silver eels in Oakland Lake, Lunenburg County, N.S. was initiated as a partnership between the Bluenose Coastal Action Foundation, DFO, and elver licence holders (currently represented by the Canadian Committee for a Sustainable Eel Fishery). This project has been studying the abundance, growth rates, and habitat preferences of yellow eels since 2009 and the run size and size at maturity of silver eels since 2012. It is hoped that the project will be ongoing, and will be augmented by a survey of silver eels leaving East River-Chester, which began in late summer 2014.

In 2013, an industry-led survey of yellow eels was initiated on the Musquodoboit River, in response to a need identified by DFO Science for better understanding of yellow eel abundance and dynamics. An elver monitoring component on Eel Pond, a tributary of the Musquodoboit River, was added in 2014. As this initiative is in the early stages, the methodology is still being developed and no preliminary data are available.

Bradford (2013) summarizes key areas of uncertainty for eel stock assessment:

Rational catch quotas for the stock of eels in any river are difficult to set in light of panmixia and uncertainty in knowledge of important life history parameters. Uncertainties include the dynamics of reproduction (e.g. required sex ratio), the causes and rates of larval/elver marine mortality, and the factors affecting offshore and inshore coastal distribution and movement. Investigations into other aspects of eel biology indicate that variability among habitats and biogeographic regions can be anticipated including elver recruitment to rivers, yellow eel mortality rates, size- and age-at maturity, fecundity and silver eel escapement, and the contributions of geographic regions to the total spawning stock (COSEWIC 2006).

An area of particular interest related to developing elver quotas is the role of density-dependence in the early freshwater stages of eel life-history. Some studies show evidence of higher survival rates and increased growth rates of juvenile eels at lower densities. As stated in DFO (2014), “Our understanding of the threat of elver fisheries and the effectiveness of mitigation measures is limited by the uncertainties associated with the degree of density-dependent survival that occurs between the elver and the silver eel stage.”

3. Socio-economic Profile of the Elver Fishery in the Maritimes Region

3.1. Quota and Landed Weight:

The annual Total Allowable Catch (TAC) for elver (i.e. glass eel) in Maritimes Region was 11,067 kilograms (wet weight) during the 2002 to 2004 period, decreasing to 9,960 kilograms (wet weight) annually from 2005 through 2016.

Total annual landings of elver by the nine licence holders in Maritimes Region averaged approximately 2,900 kilograms (wet weight) during the 2002 to 2010 period. Landings increased to approximately 6,800 kilograms (wet weight) in 2013, before declining to approximately 4,800 kilograms (wet weight) in 2016. Note that the 2015-2016 data is preliminary (p).

Source: DFO Maritimes Region

3.2. Average Price:

During the 2002 to 2010 period, the average annual price of elver in the Maritimes Region ranged from $112 to $787 per kilogram (wet weight), with an average of $393 per kilogram (wet weight) for the period.

In 2011, the average price increased dramatically to almost $2,000 per kilogram (wet weight), and then doubled to just over $4,000 per kilogram (wet weight) in 2012. Prices have fluctuated in recent years, peaking at $4,685 per kilogram (wet weight) in 2015 before declining to just under $3,000 per kilogram (wet weight) in 2016 (preliminary).

Source: DFO Maritimes Region

3.3. Landed Value:

Dramatic price increases have driven substantial increases in elver landed value in recent years, growing from a maximum of approximately $2.4 million during the 2002 to 2010 period, to $8.2 million in 2011. Subsequently, elver landed value nearly tripled in one year, increasing to $23.0 million in 2012 and $22.9 million in 2013. Landed value dropped to $9.8 million in 2014 before rising to $16.9 million in 2015 and $15.6 million in 2016 (data is preliminary).

Source: DFO Maritimes Region

3.4. Average Landed Value per Licence Synopsis:

The average landed value per elver licence in Maritimes Region has increased dramatically in recent years, rising from an annual average of $123,000 for the 2002-2010 period, to up to $2.5 million in both 2012 and 2013, declining to just over $1.7 million in 2016.

Source: DFO Maritimes Region

3.5. Global Supply Context:

While older eels are sold for their meat, elvers (also known as glass eels) are sold to aquaculture facilities, particularly in Asia, for the purpose of growing them to adult size for later consumption. As the main species of eel are morphologically similar and assumed to be substitutes in the market, significant declines in the global capture production of eels (and elvers) in recent years appear to have helped improve market conditions for elvers harvested in Atlantic Canada and the northeastern US.

The total capture of eels peaked in 1971 at just over 26,000 tonnes according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Total catch declined to 7,165 tonnes in 2011, increased to just over 14,000 tonnes in 2012, and then declined to 10,653 tonnes in 2014. Figure 8 shows the capture of eel by species globally from 1950 to 2014.

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Note: “nei” stands for “not elsewhere included”

European eel has been the dominant species over time, with harvests reaching nearly 20,000 tonnes in 1968 when it accounted for approximately 70 percent of global capture. Although catches of European eel have decreased, it has remained the major species of eel harvested globally.

On March 13, 2009, the 174 member countries of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) announced the regulation of the international trade of European eels. By the late 2000s, around half of the eels caught in Europe were exported to China, Japan and South Korea, amounting to over 200 million eels per year. Overfishing in combination with habitat loss, pollution, the damming of rivers, and changing ocean currents were all thought to have contributed to the sharp decline in European eel populations in the years leading up to that point. The stock of European elvers was estimated to have declined by 95 to 99 percent since 1980 (CITES 2009).

The capture of Japanese eels declined from a peak of 3,619 tonnes in 1969 after which they fluctuated between a harvest of 2,000 and 3,000 tonnes annually; capture levels have been in decline steadily since 1981 and reached 199 tonnes in 2014. The quantity of Japanese glass eels caught in Asia has fallen considerably over the last four decades (FAO 2014). For example, the catches of Japanese glass eels in estuaries in Japan decreased from a peak of 174 tonnes in 1969 to 14 tonnes in 2001. During the same period, catches of Japanese yellow and silver eels in Japanese freshwater habitats decreased from 3,194 tonnes to approximately 677 tonnes. Other recent evidence, such as genetic analysis, suggested that the population size of Japanese eels had declined (Tsukamoto et al. 2009).

The capture of American eels has remained relatively stable, particularly in recent decades, although the 2014 harvest figure of 885 tonnes is below the 20 year average of 1,001 tonnes. With respect to elvers or glass eel, the supply in many parts of North America has been restricted due to the damming of rivers and other habitat blockage or alteration; many jurisdictions have closed their fisheries.

As of 2016, only Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Maine and South Carolina have elver fisheries. As discussed previously, the elver landings in Maritimes Region averaged approximately 2,900 kilograms (wet weight) per year from 2002 to 2010 and increased to approximately 6,800 kilograms (wet weight) in 2013. From 2002 to 2013, the landed value increased from $2.5 million to $22.6 million before declining to $15.4 million in 2016. The elver fishery in Maine increased from 3,153 kilograms in 2008 to 21,611 kilograms in 2012 before declining to 5,259 kilograms in 2015. From 2008 to 2012, the total landed value increased from US$ 1.5 million to US$ 38.8 million, declining to $11.4 million in 2015 (Maine Department of Marine Resources 2016). Data on the landings of elver in South Carolina was not readily available.

Catches of eel shown in the FAO data as “river eels, nei (not elsewhere included)” has grown since the early 1970s. In 2014, catches of eels in this category totaled 6,147 tonnes (or 58 percent of global eel capture); about 90 percent of ‘river eels’ captured were in Asia with the remainder in Oceania.

3.6. Canadian Exports:

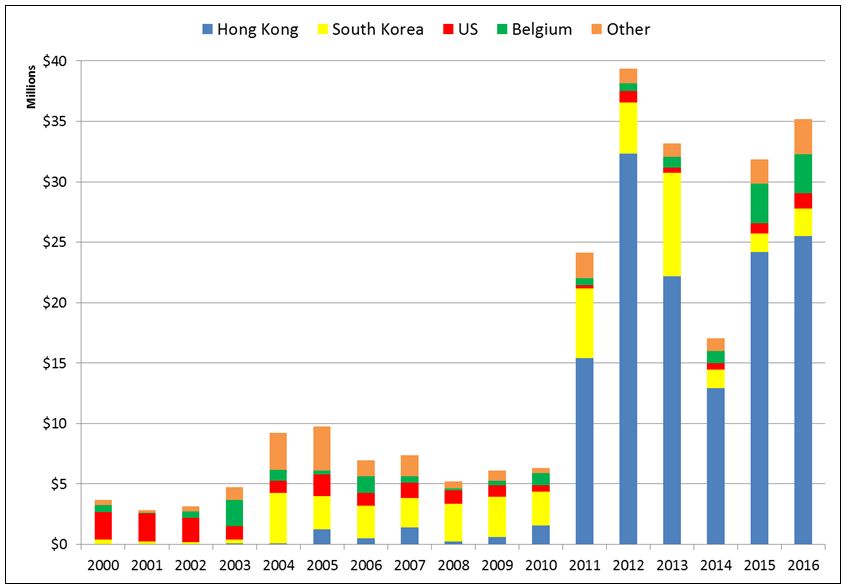

As Canada’s export data for eel does not specify elver, the export value for elver is included in the Canadian total export value for eel/elver. Eel landed value in the Maritimes Region is relatively small, compared to that for elver (as shown in Figure 6). The value of Canadian exports of eel/elver totaled $35.2 million in 2016, second all-time after $39.4 million in 2012. This represented a five-fold increase over the average export value during the 2000 to 2010 period.

The vast majority of this export value was generated by shipments to Asia, with that market accounting for 93 percent of 2012 eel/elver exports, declining to 79 percent in 2016. Of these Asia market shipments, exports to Hong Kong accounted for $25.5 million in 2016, a large portion of which presumably entered China. The South Korean market accounted for $2.3 million in export value. Exports to Belgium increased significantly for 2015 and 2016, reaching just over $3.2 million in each year. The remainder of Canadian eel/elver exports was shipped to the US and to other European countries.

Source: DFO Economics and Statistics

4. Management Issues

4.1. Managing Fishing Mortality – Quota Setting and Input Controls:

One of the objectives of the fishery is to ensure that it is not impeding the ability of eels to play their role in the functioning of the ecosystem, at all spatial scales. Exploitation of elvers is managed through a mix of individual quotas, river catch limits, and effort controls. Quotas were set based on science advice provided by Jessop (1995, 1996) and, in the absence of total population size or recruitment estimates for eels in the Region, were intended to be used in combination with effort controls. Annual river catch limits of 400 kg wet weight per river were set based on run size estimates from the East River-Chester, NS, and catch rates in exploratory fishing (Jessop 1995). Since that time, DFO has begun implementing a new approach of scaling river catch limits based on total watershed size, and so many river catch limits have been reduced. Quotas and river catch limits should be reviewed during the next American Eel stock assessment in the Region, to ensure that they are biologically appropriate and in line with national and regional goals and objectives.

Estimates of elver abundance in the Region have come from the East River-Sheet Harbour (1990-1999) and the East River-Chester (1996-2002 and 2008-2013; Figure 2). When quotas and river catch limits were being set, these time series were very short, and there was and is high uncertainty about the size and variability of elver runs and how run size estimates from these rivers could be extrapolated across the Region. Effort controls, including the number of rivers authorized for fishing, the gear types and amounts, and the number of employees authorized to fish under a given elver licence, were imposed in order to ensure that fishing mortality remained moderate in all river systems.

Individual quotas are 1,200 kg wet weightFootnote 3 for most licence holders, and 360 kg wet weight for one licence holder, for a TAC of 9,960 kg wet weight annually (2005-2017). Quotas were typically reported in dry weight3 from the inception of the fishery until 2015, such that the quota was reported as 7,470 kg dry weight from 2005-2014.

While some licence holders have caught their quota in some years, the total catch has never exceeded 70% of the TAC, and has generally been much lower. The relative roles of quotas, river catch limits, effort controls, economic incentives, and the availability of elvers in limiting elver catches in the Region have not been analyzed. In some cases, catches are limited by the licence holder’s individual quota, while in other cases, the amount or type of gear available, or the amount of elvers available in the licensed rivers, may be the limiting factor. In this context, management decisions have been conservative and the effort controls have typically been static, particularly since 2005. That is, licence holders have not been permitted to increase the amount of gear or number of persons authorized to fish under their licence, or the number of rivers licensed for fishing.

In recent years, especially given the relatively high prices for elvers, many licence holders have requested changes to input controls such as gear type, number, and size, in order to increase their chances of reaching their individual quota. Over time, a shift to more quota-based management rather than input controls may provide the best means to manage mortality while allowing licence holders to fish their allocations efficiently.

4.2. Ensuring Adequate Escapement Across Multiple Life History Stages:

To ensure that a sufficient number of eels escape exploitation over their lifetime and contribute to the spawning stock, DFO must consider fisheries on large eels when making management decisions in the elver fishery. There is a policy in place for the elver fishery to avoid overlap with large eel fishing. However, because large eel fishers can begin fishing a river after elver fishing has been licensed in that river, there are several rivers in the Region where eels are fished at the elver and yellow eel and/or silver eel stages. An assessment of the spatial extent of both fisheries and their spatial overlap has been made a priority for future scientific assessment of the fishery.

Because of the very high natural mortality at the elver stage, large eel fisheries, particularly those targeting silver eels, may have more impact on the number of eels surviving to reproduce than elver fisheries (Jessop 1995). For this reason, DFO has supported proposals by elver licence holders to buy and relinquish to the Crown active large eel licences in some river systems, and permitted elver fisheries in those river systems. Whether this results in a higher or lower exploitation of eels in any particular river system, or across the Region, would depend on the intensity of both fisheries and the recruit to spawner (elver to large eel) relationship. The effectiveness of this tactic in reaching eel mortality goals in Atlantic Canada should be evaluated.

4.3. Supporting Recovery of American Eels:

As described in Section 1.1, in 2005 a number of management changes were made in the elver fishery in response to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans’ directive to reduce overall anthropogenic mortality of American Eels by 50% (relative to the 1997 to 2002 average). This is still one of the key management goals for eel and elver fisheries in Canada. Management decisions must not lead to an overall increase in fishing mortality for eels in the Region until conservation goals have been achieved. In addition to maintaining standing stock biomass of eels in rivers in the Maritimes Region, ensuring adequate escapement of spawning stock, particularly large female eels, is an important contribution to the persistence and recovery of the species.

The provision of elvers to Ontario Hydro for conservation stocking purposes also supports the persistence and recovery of the species, as well as the standing stock biomass in Ontario. While this project is currently on hiatus due to the discovery of the eel swim bladder parasite in the DFO Maritimes Region and due to unexpected growth patterns and early maturation of the stocked eels in Ontario waters, contributions to stocking in other regions of Canada may be considered by the Elver Advisory Committee in future.

4.4. Potential for Spread of the Eel Swim Bladder Parasite, A. crassus:

The swim bladder parasite, A. crassus, is a native parasite of Japanese Eels that has spread into American Eel populations. The parasite was first detected in Nova Scotia in 2007 (Rockwell et al., 2009; Campbell et al., 2010). Campbell et al. (2010) conducted the first systematic survey of the presence of A. crassus in the Maritime Provinces. Necropsies of 1,966 eels collected from 175 sites distributed within 63 drainages in the Maritimes found the parasite in six drainages. Overall prevalence and intensity of infection within the six drainages were considered low.

The effects of this parasite on viability of American Eel are not well understood, but Palstra et al. (2007) have linked the collapse of the European Eel to A. crassus and suggested that migrating silver eels with severely infected or damaged swim bladders are unable to reach the spawning grounds. In anguillid eels other than Japanese Eels, infection of the swim bladder by A. crassus may affect eel survival by directly causing bladder dysfunctions and by decreasing the host’s energy level (Rockwell et al., 2009).

Dispersal of A. crassus within aquatic systems is generally through the natural movements of infected hosts (COSEWIC 2012). Spread between distant localities is generally through human transport of infected eels (Machut and Limburg, 2008). There is a risk that elver fishers could spread the parasite by moving gear and boots among river systems, though there is a requirement in licence conditions to treat gear and boots prior to moving between watersheds in order to mitigate this risk.

4.5. Potential for Localized Overexploitation:

River catch limits of 400 kg wet weight per river were established for most rivers and streams in 1998. There is a risk that elvers could be overexploited at this amount, particularly at a local level, resulting in a substantial decrease in the standing stock of adult eels in some river systems. This catch limit likely represents a large proportion or even the full run size to some river systems in some years. For example, estimates of the total run size at East River Chester indicate that the current 400 kg river catch limit represents 158% of the run in an average year, and exceeds the total run size in most of the last 13 years. It should be noted that the actual exploitation rates were well below the total run size in all years (maximum exploitation of 59%), and that it is expected that licence holders would typically find it more economical to spread their effort among their licensed rivers than to exploit a very high proportion of a single run. The potential for eels to redistribute themselves among watersheds and to enter watersheds at later life history stages is not fully understood, and may mitigate the impacts of exploitation at the glass eel stage to some extent. However, river catch limits that are proportional to the expected run size in the river and ensure that elvers are not being locally overexploited are needed. With this in mind, DFO has begun implementing a new approach of scaling river catch limits based on total watershed size, and so many river catch limits have been reduced in recent years. As additional science advice becomes available to support the setting of appropriate river catch limits, additional revisions may be required.

4.6. Depleted Species Concerns:

A number of Canada’s freshwater wildlife species are considered to be at risk. Ensuring protection and promoting recovery of at-risk species is a national priority. To this end, Canada developed the Species at Risk Act (SARA) and a number of complementary programs to promote recovery and protection of species considered to be extirpated, endangered, threatened or of special concern under SARA or identified as such by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

The American eel has been assessed by COSEWIC as threatened and a determination on its SARA status is pending. However, once assessed by COSEWIC, if a decision is made not to list a species under SARA, DFO is required to develop an “alternative approach” to species conservation using other legislative or non-legislative tools. If the “alternative approach” includes incremental actions, a 5-year workplan must be developed as per the Species at Risk Act Listing Policy and Directive for Do Not List Advice.

To support the recovery of species at risk, SARA includes prohibitions that protect endangered, threatened, and extirpated species (Section 32), their residences (Section 33), and their critical habitat (Section 58). Provided specific criteria can be met, SARA allows activities that would otherwise be prohibited to proceed through the issuance of permits or agreements under Section 73 and 74, or through exemptions under Section 83(4). The recovery of species at risk involves the development and implementation of recovery strategies, action plans or management plans, and the protection of any critical habitat that has been identified as necessary for the survival or recovery of the species. For species listed as special concern, critical habitat is not identified and the section 32 prohibitions do not apply.

Further information on SARA can be obtained online:

http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=en&n=24F7211B-1

The elver fishery has not been identified as a threat to any species listed under the Species at Risk Act in Canada. Screening devices required under licence conditions eliminate bycatch of any SARA listed species.

| Species | Population/Range | SARA Status |

|---|---|---|

| Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) | Inner Bay of Fundy | Endangered |

| Atlantic Whitefish (Coregonus huntsman) |

Nova Scotia | Endangered |

| Shortnose Sturgeon Acipenser brevirostrum) |

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia |

Special Concern |

Should additional species be listed under SARA, this IFMP recognizes there will be a need to address potential impacts to these new species. Industry will be consulted as required to develop any necessary strategies to mitigate these impacts.

4.7. Gear Impact on Biodiversity and Habitat:

Bycatch is not generally thought to be a problem in the elver fishery. A review of logbooks for 2012 and 2013 indicated that only larger eels were reported as bycatch in the fishery. Due to the gear types used, any incidental catch is generally immediately apparent and can be released alive. Licence conditions require screening devices in elver traps and elver pots to prevent other species from entering the gear.

Elver fishing gear is generally considered to be minimally disruptive to fish habitat. No permanent structures are built, and at least one-third of the watercourse (or two-thirds of a tidal stream at low tide) must be unobstructed at all times, as required under the Fisheries Act.

4.8. River Changes and Flexibility:

Licence holders have requested flexibility to change fishing locations. DFO has allowed licence holders to exchange a currently licensed river for a new river, provided that there is no active fishery for large eels in the river system being requested, and subject to other considerations described in Appendix 5. In the early years of the fishery, considerable flexibility around gear types and fishing locations was provided, in order to let the fishery develop. Since 2005, no increases to the amount of gear, the number of people permitted to fish, or to the total number of rivers licensed for elver fishing have been permitted, and changes to gear type have been permitted only in exceptional circumstances. However, some flexibility has been permitted to exchange fishing locations as per the policy described in Appendix 5.

The 1998 elver IFMP stated that “Each licence holder is authorized to fish specific rivers within a defined geographic area… Except in the area set aside for harvesting for aquaculture purposes, there will be no overlapping fishing areas.” These non-overlapping fisheries areas have been known as “territories” and have been informal. Over the last few years, a few licence holders have requested and been granted access to new rivers such that they now have multiple fishing areas, across different parts of the Region. The management issue related to territories is whether or not a licence holder should have exclusive access to a given area, such as a county, even if all the rivers in that county are not on their licence. Discussions at the advisory committee have indicated that licence holders are not in agreement, with some licence holders wanting to maintain exclusive access to a territory and other licence holders wanting access to new areas. Some licence holders felt that access to a river in someone else’s territory should only be permitted if the person seeking access purchased and relinquished active large eel licences in the river in question. The policy for river exchanges described in Appendix 5 will require further discussion and revision to address this and other related issues. This matter should be addressed through the Advisory Committee, for clarity and to allow licence holders to plan accordingly. If territories are maintained in some form as part of the management of the fishery, their role and spatial extent needs to be made explicit.

4.9. Quota Transferability:

No quota transfers have been permitted in the elver fishery. Recently, there have been requests from some licence holders to transfer their quota on a temporary basis to other licence holders who have caught their quota. The requests have been denied because management goals have necessitated being very conservative when making management decisions, and quota transfers into licensed rivers would increase mortality of elvers in those systems. However, there may be some potential to allow limited quota transferability in future, subject to a review of quotas and river catch limits and to a reduction in large eel fishing capacity, as a way to constrain overall anthropogenic mortality in the Region.

4.10. Traceability:

A dramatic recent increase in the price paid for elvers has increased concerns about the potential for illegal elver fishing in the Maritimes. In addition to the work being led by DFO Conservation and Protection Branch, detailed in Section 9, licence holders and DFO have been working together to increase the traceability of elvers caught in the Region. Under licence conditions, a paper trail must be maintained from the river until the point of sale. Logbooks are used to document catches at the river, and track transport of elvers from the river to the holding facility. The logbooks also record a running totals of elvers kept at holding facilities, as well as information on sales. Dockside Monitoring Companies independently maintain hail-out and hail-in records, monitor some instances of elvers arriving from the rivers to the holding facility to be weighed, and monitor all elver sales. A summary of reporting and monitoring procedures for the elver fishery in 2017 are in Appendix 4.

The Canadian Committee for a Sustainable Eel Fishery has been working with DFO, the Provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and CFIA to develop stricter traceability protocols from the point of sale onwards. Sales made in Canada should be reported to the Provinces through regular Buyer Reports. Improving and streamlining reporting procedures from the river to the ultimate destination in Eel farms will be an ongoing priority for the Elver Advisory Committee.

4.11. Data Collection and Data Quality:

In general, fisheries and sales data for the elver fishery are quite detailed and compliance with reporting requirements is good. Some areas for improvement have been identified, including ensuring that all licence holders are providing logbook information in a correct and consistent manner, and that Dockside Monitoring Companies are also inputting this data into DFO’s database in a correct and consistent manner, to ensure a high level of data quality. A new Elver Fishery Monitoring Document (logbook) was developed and implemented in the fishery starting in 2015. This new logbook allows for more comprehensive data collection that is specific to this fishery, and should improve the information available on the elver fishery going forward. However, implementation of a new logbook and new reporting requirements entailed a learning curve for all users to adjust to the new requirements and format. Work continues with the goal of ensuring that instructions are clear and communicated, and that data quality for this fishery is sufficiently high to support science and management needs.

4.12. International Issues - Trade:

The US is developing new import rules to address illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, seafood fraud (which includes traceability requirements), and marine mammal protection. Traceability requirements will initially be applied to imports of listed at-risk species, but this list is to be expanded.

American Eel has been discussed for possible listing on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The 17th meeting of the CITES Conference of the Parties (“CoP17”), held in September – October 2016, made recommendations to enable a better understanding of the effects of international trade on the conservation of eel species, including trade in their various life stages, and possible measures to ensure sustainable trade in such species. Should American Eel be listed under CITES, restrictions or prohibitions could be introduced on the import or export of American Eel.

5. Objectives

There are five overarching objectives that guide fisheries management planning in the DFO Maritimes Region. They are guided by the principle that the fishery is a common property resource to be managed for the benefit of all Canadians, consistent with conservation objectives, the constitutional protection afforded Aboriginal and treaty rights, and the relative contributions that various uses of the resource make to Canadian society, including socio-economic benefits to communities.

Conservation objectives

- Productivity: Do not cause unacceptable reduction in productivity so that components can play their role in the functioning of the ecosystem.

- Biodiversity: Do not cause unacceptable reduction in biodiversity in order to preserve the structure and natural resilience of the ecosystem.

- Habitat: Do not cause unacceptable modification to habitat in order to safeguard both physical and chemical properties of the ecosystem.

Social, cultural and economic objectives

- Culture and Sustenance: Respect Aboriginal and treaty rights to fish.

- Prosperity: Create the circumstances for economically prosperous fisheries.

The conservation objectives are those from the DFO Maritimes Region’s framework for an ecosystem approach to management (EAM framework). They require consideration of the impact of the fishery not only on the target species but also on non target species and habitat. (See Appendix 1 for a summary of the regional EAM framework.)

The social, cultural and economic objectives reflect the Aboriginal right to fish for food, social and ceremonial purposes. They also recognize the economic contribution that the fishing industry makes to Canadian businesses and many coastal communities. Ultimately, the economic viability of fisheries depends on the industry itself. However, the Department is committed to managing the fisheries in a manner that helps its members be economically successful while using the ocean’s resources in an environmentally sustainable manner.

The overarching social, cultural and economic objective is thus to help create the circumstances for economically prosperous fisheries wherein fishing enterprises are more self-reliant, self-adjusting and internationally competitive.

For the purposes of sustainability certification, these five objectives are considered by DFO to be the long term objectives for the fishery.

6. Strategies and Tactics

This section of the IFMP presents the strategies and tactics being used in this fishery to achieve the objectives listed in Section 5. For a general description of strategies and tactics in the context of the regional EAM framework, please see Appendix 1.

| Strategies | Tactics |

|---|---|

| Productivity | |

Keep fishing mortality of American Eels moderate (reference: overall anthropogenic mortality at 50% of 1997-2002 levels) |

|

| Allow sufficient escapement from exploitation for spawning |

|

| Control introduction and proliferation of disease/pathogens, particularly A. crassus |

|

| Biodiversity | |

| Distribute population component mortality in relation to component biomass, such that the standing stocks of American Eel in all suitable rivers are maintained |

|

| Control unintended mortality for all species |

|

| Minimize unintended introduction and transmission of invasive species |

|

| Habitat | |

| Manage area disturbed of habitat |

|

| Culture and Sustenance | |

| Provide access for food, social and ceremonial purposes |

|

| Prosperity | |

| Limit inflexibility in policy and licensing among individual enterprises/licence holders |

|

| Minimize instability in access to resources and allocations |

|

6.1. Productivity

Strategy: Keep fishing mortality of American Eels moderate

A number of management measures have been put in place to moderate the fishing mortality of elvers, including individual quotas. Any quota overruns that might occur are to be deducted from a licence holder’s quota the following year. The fishing season varies with latitude, but generally begins in late March and runs until July 31st. The maximum size limit is 10 cm.