Northern shrimp – Areas 8, 9, 10 and 12 (Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence)

Foreword

Northern shrimp

(Pandalus borealis)

The purpose of this integrated fisheries management plan (IFMP) is to identify the main objectives and requirements of the northern shrimp fishery in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence, in the Esquiman (8), Anticosti (9), Sept-Îles (10) and Estuary (12) areas and the management measures that will be used to achieve these objectives. This document also provides background information and information related to management of this fishery to staff of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), co-management boards established by law under the regulations on territorial claims (if applicable) and other stakeholders. This IFMP provides a common interpretation of the fundamental "rules" that govern sustainable management of fisheries resources.

This IFMP is not a legally binding instrument which can form the basis of a legal challenge. The IFMP can be modified at any time and does not fetter the Minister's discretionary powers set out in the Fisheries Act. The Minister can, for reasons of conservation or for any other valid reasons, modify any provision of the IFMP in accordance with the powers granted pursuant to the Fisheries Act.

Where DFO is responsible for the implementing obligation under land claim agreements or from Supreme Court judgments in relation to aboriginal rights, the IFMP will be implemented in a manner consistent with these obligations. In the event that an IFMP is inconsistent with obligations under land claim agreements, the provisions of the land claim agreements will prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.

Maryse Lemire

Regional Director, Fisheries Management

Quebec Region

Table of contents

- Foreword

- List of figures

- Acronymes

- 1. Overview of the fishery

- 2. Distribution, scientific and traditional knowledge and stock assessment.

- 3. Economic significance of the fishery

- 4. Management issues

- 5. Management objectives

- 6. Access and allocation

- 7. Management measures

- 8. Shared Stewardship management

- 9. Compliance Plan

- 10. Performance review

- 11. Glossary

- Appendix 1: Monitoring progress toward attaining the management objectives based on performance indicators

- Appendix 2 : Mandate of the Estuary and Gulf Shrimp Advisory Committee

- Appendix 3: Bycatch protocol

- Appendix 4: Strategic research plan

- Appendix 5 : Partial strategy

- Appendix 6: Compliance monitoring

- Appendix 7: Contact persons

- Appendix 8: Safety of fishing vessels at sea

- Appendix 9: Reference

List of figures

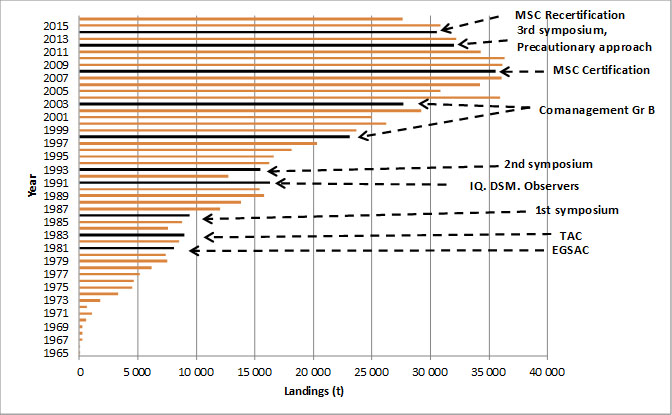

- Figure 1: Historical landings of the shrimp fishery in the estuary and the north of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and highlights of management measures in the fishery between 1965 and 2016p

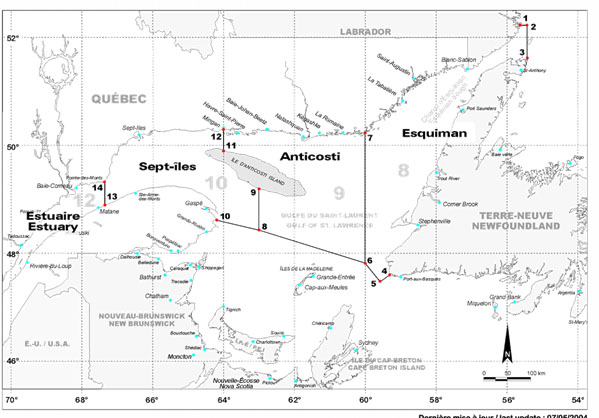

- Figure 2: Shrimp fishing areas for the Gulf

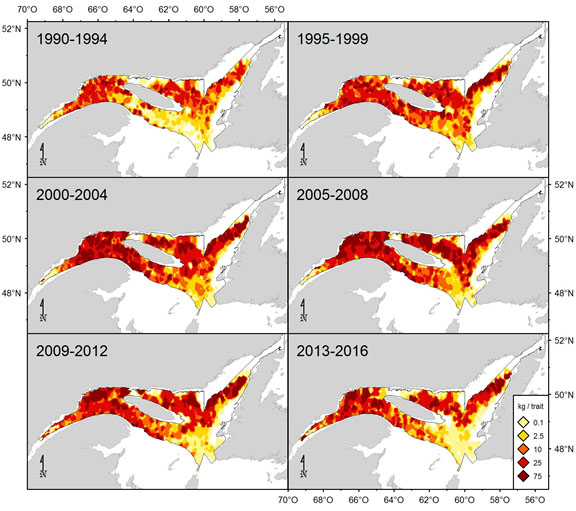

- Figure 3 : Northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) distribution as determined by research surveys from 1990 to 2016

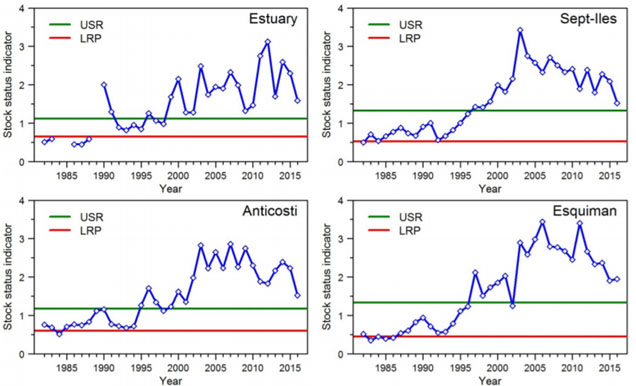

- Figure 4 : Main stock status indicator by year and limit (LRP) and upper (USR) stock reference points for each fishing area in 2016

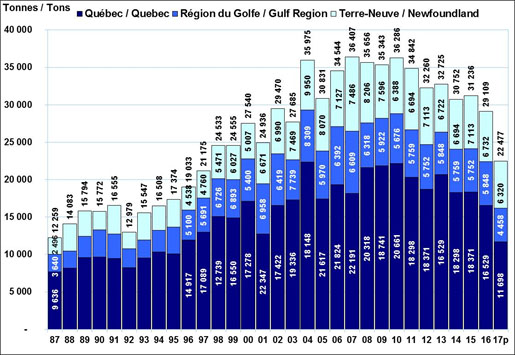

- Figure 5: Northern shrimp landed volume (tonnes), by region, 1987–2017p

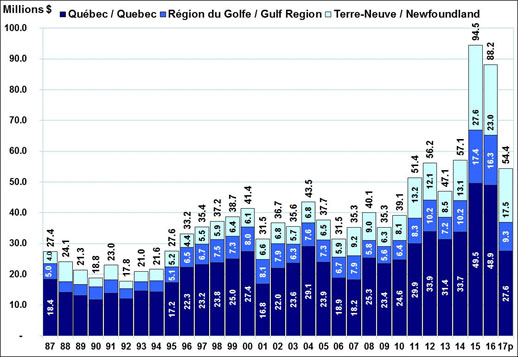

- Figure 6: Northern shrimp landed value (Millions $), by region, 1987–2017p

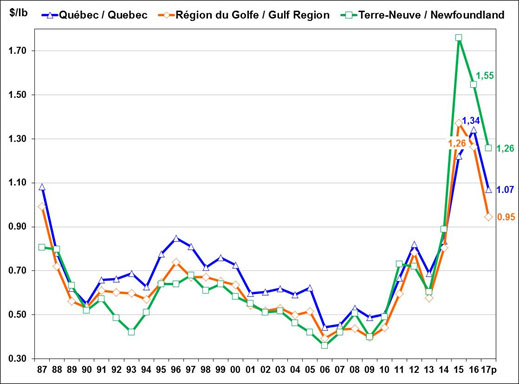

- Figure 7: Average landed price of Northern shrimp ($/lb), by region, 1987–2017p

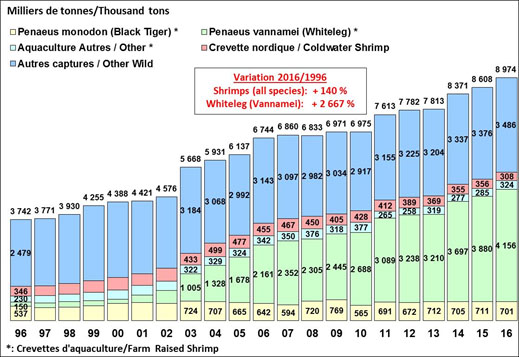

- Figure 8: Worldwide shrimp production (wild and farmed), 1996–2016

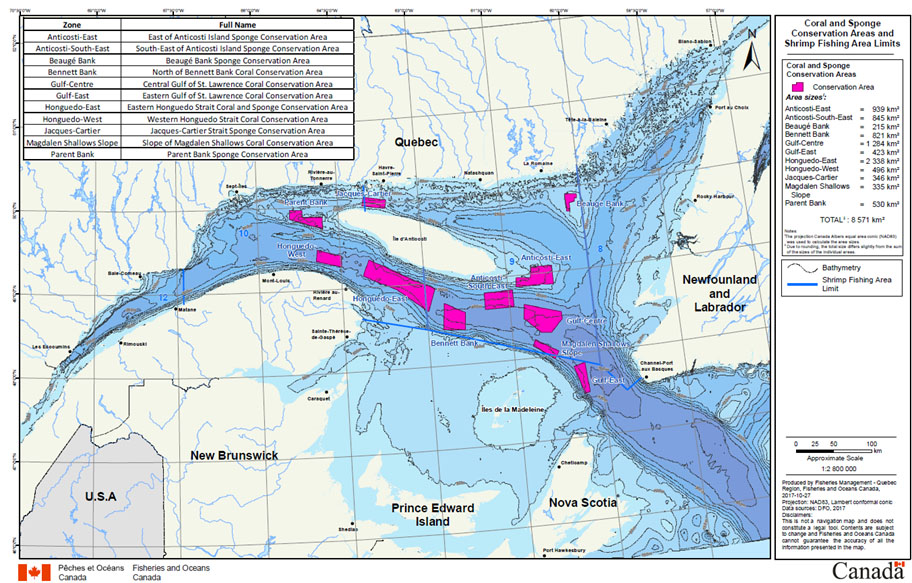

- Figure 9 : Coral and sponge conservation areas and the boundary lines of the Gulf shrimp fishing areas in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence

Acronymes

- ACAG

- Association des crevettiers Acadiens du Golfe

- ACPG

- Association des capitaines propriétaires de la Gaspésie

- AFS

- Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy

- CCG

- Canadian Coast Guard

- CL

- Carapace length

- C&P

- Conservation and protection branch

- CSAS

- Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat

- CSSP

- Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program

- CSST

- Commission de la santé et de la sécurité au travail

- DFO

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- ENGO

- Environmental Non-Governmental Organisation

- FAO

- Food and Alimentation Organisation of the United Nations

- FFAW

- Fish, Food and Allied Workers

- EGSAC

- Estuary and Gulf Shrimp Advisory Committee

- IFMP

- Integrated Fishery Management Plan

- IQ

- Individual Quota

- ITQ

- Individual Transferable Quota

- LRP

- Lower Reference Point

- OEABCM

- Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures

- MSC

- Marine Stewardship Council

- PA

- Precautionary approach

- SARA

- Species at Risk Act

- SFA

- Shrimp Fishing Area

- SRP

- Superior Reference Point

- SS

- Strategic Services branch

- TAC

- Total Allowable Catch

- TC

- Transport Canada

- TRP

- Target Reference Point

- UNFA

- United Nations Agreement on Straddling and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks

- VMS

- Vessel Monitoring System

Overview of the fishery

History

Beginning of the commercial fishery

The 1960s and 1970s correspond to the start of the northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) fishing industry throughout Atlantic Canada. During the 1960s, intensive programs of exploratory fishing identified interesting concentrations of shrimp in the Bay of Fundy and on the Scotian Shelf as well as in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Saguenay Fjord. The small fisheries of the Bay of Fundy and the Saguenay Fjord did not persist. Some fishermen continued the exploration and new sites were exploited during the 1970s in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence as well as on the Labrador Coast.

The northern Shrimp fishery began in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1965 when the first commercial catches were made in the western Gulf (Figure 1 ). The shrimp fishery was essentially developed by mid-shore groundfish harvesters who chose to diversify their fishing operations. Fishing targeting shrimp intensified and the use of higher performance fishing vessels and gear contributed to the rapid increase of landings. Indeed, the collapse of cod and redfish stocks in the mid-1970s and the low prices paid for these species led to increased demand for fishing licences for northern shrimp. The number of northern shrimp fishing licences increased until 1980 to a limit of 111 licences. The number had to be limited so as to not further increase fishing capacity on groundfish species since all the northern shrimp fishing licence holders were also holders of groundfish fishing licence.

Management measures history

The Gulf Shrimp Advisory Committee was created in 1980 and measures for better control of catches were put forward, such as implementing a Total Allowable Catch (TAC) in 1982.

A symposium of all stakeholders in the Gulf shrimp fishery took place in March 1985 to discuss the suitability of issuing new fishing licences, distributing quotas between harvesters and new measures to reduce incidental catches of groundfish. Following this symposium, the number of licences authorized for shrimp increased by over 20% between 1985 and 1990, reaching 134.

During this period, shrimp fishing was done by two groups of fish harvesters, which were defined in the mid-80s. Group A consists of harvesters from Western Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec, while Group B consists of fish harvesters from Quebec and New Brunswick. An individual quota program was established for Group B in 1991 and for Group A in 1996.

In the winter of 1993, fisheries managers held a second symposium on the Gulf shrimp in order to take stock of the fishery and plan for medium term management. The symposium brought together many industry stakeholders who were able to discuss in a more open setting than that of the Gulf Shrimp Advisory Committee. A three year management plan (1993-1995) was adopted following this conference and several management measures were changed or strengthened. In addition to conservation objectives, the management strategy was also aimed at socio-economic objectives such as maximizing harvesters' profits, avoiding over-capitalization and ensuring equitable sharing of the resource.

The northern shrimp industry was able to expand while continuing its efforts in rationalization and long-term planning while harvesters other than shrimp harvesters were also able to benefit from increases in quotas from 1997 in all areas. After that, temporary shrimp allocations (« new access ») were allocated to harvesters who do not hold a regular shrimp fishing licence, mainly groundfish fishers of Quebec and New Brunswick.

In 1998, a temporary allocation was authorized to benefit core groundfish harvesters of Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. Temporary allocation quotas were dependent on the TAC and, therefore, varied based on shrimp stock abundance in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In 2009, DFO stabilized access for the various fleets involved in the shrimp fishery.

Between 1998 and 2008, two co-management agreements (1998-2002 and 2003-2007) were in effect between the DFO and the traditional shrimp harvesters of Group B. These co-management agreements established basic principles for the management of northern shrimp for a period of 5 years. The basic principles were the conservation of the resource, the viability of the traditional shrimp fleet and no permanent increase in fishing capacity. These agreements put in place a resource-sharing formula between shrimpers and other fishers, and allowed the identification of additional activities financed by the industry (for example, Section 2.4).

Figure 1 : Historical landings of the shrimp fishery in the estuary and the north of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and highlights of management measures in the fishery between 1965 and 2016p

Source: DFO, Quebec Science Region

Description

Figure 1 shows historical landings of the shrimp fishery in the estuary and the north of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and highlights of management measures in the fishery between 1965 and 2016p*

| Year | Total (tonnes) | Highlights of management measures in the fishery |

|---|---|---|

| 1965 | 11 | |

| 1966 | 95 | |

| 1967 | 278 | |

| 1968 | 271 | |

| 1969 | 273 | |

| 1970 | 572 | |

| 1971 | 1 084 | |

| 1972 | 665 | |

| 1973 | 1 793 | |

| 1974 | 3 317 | |

| 1975 | 4 528 | |

| 1976 | 4 645 | |

| 1977 | 5 180 | |

| 1978 | 6 152 | |

| 1979 | 7 541 | |

| 1980 | 7 412 | |

| 1981 | 8 106 | Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence advisory committee (EGSAC) |

| 1982 | 8 501 | |

| 1983 | 8 972 | Total allowable catch (TAC) |

| 1984 | 7 545 | |

| 1985 | 8 770 | |

| 1986 | 9 410 | 1st symposium |

| 1987 | 12 041 | |

| 1988 | 13 777 | |

| 1989 | 15 750 | |

| 1990 | 15 372 | |

| 1991 | 16 279 | Individual Quota (IQ). Dockside Monitoring Program (DSM). Observers |

| 1992 | 12 757 | |

| 1993 | 15 455 | 2nd symposium |

| 1994 | 16 210 | |

| 1995 | 16 634 | |

| 1996 | 18 111 | |

| 1997 | 20 301 | |

| 1998 | 23 101 | Comanagement Group B |

| 1999 | 23 639 | |

| 2000 | 26 236 | |

| 2001 | 25 011 | |

| 2002 | 29 180 | |

| 2003 | 27 668 | Comanagement Group B |

| 2004 | 35 924 | |

| 2005 | 30 882 | |

| 2006 | 34 259 | |

| 2007 | 36 069 | |

| 2008 | 35 564 | MSC Certification |

| 2009 | 36 124 | |

| 2010 | 36 299 | |

| 2011 | 34 263 | |

| 2012 | 31 983 | 3rd symposium, Precautionary approach |

| 2013 | 32 165 | |

| 2014 | 30 546 | MSC Recertification |

| 2015 | 30 882 | |

| 2016p | 27 610 |

* Preliminary

First Nations

DFO's development of the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy took off in the wake of the Sparrow decision in the early 1990s, when subsection 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, which recognizes and affirms the ancestral and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, including the right to fish, was studied in greater detail. An initial Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) was implemented in 1992, and its objectives included governing the Aboriginal food, social and ceremonial fishery and providing Aboriginal peoples with the opportunity to participate in fisheries management. In 1994 this strategy was improved following the implementation of the allocation transfer program, which facilitated First Nations' entry into the commercial fishery without increasing pressure on stocks. Commercial fishers could voluntarily sell their allocations to DFO, which would redistribute them to First Nations groups through communal licences.

On September 17, 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada handed down the Marshall decision, which affirmed, to Mi’kmaq and Meliseet First Nations, the aboriginal right to hunt, fish and gather in pursuit of a “moderate livelihood,” stemming from Peace and Friendship Treaties of 1760 and 1761. This decision affected the 34 Mi’kmaq and Maliseet First Nations in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Quebec (Gaspé). The Supreme Court made a clarification on November 17, 1999, stating that this right had its limits and that this fishery could be regulated.

In response, in January 2000, Fisheries and Oceans Canada launched the Marshall Response Initiative to negotiate interim fisheries agreements, giving First Nations increased and immediate access to the commercial fishery. This initiative was largely inspired by the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS). The Marshall Response Initiative was in effect until 2007.

The Marshall Response Initiative's long-term objectives were the following:

- to provide Mi’kmaq and Maliseet communities in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Quebec (Gaspé) with access to commercial fisheries;

- to assist First Nations in building and managing their fishing activities; and

- to maintain a peaceful and orderly commercial fishery.

In 2000, after buying back 6 Quebec licences, First Nations from Gesgapegiag, Gespeg, Listuguj and Viger Maliseet gained access to the shrimp fishery. In New Brunswick, First Nations from Eel River Bar and Red Bank gained access in 2004, after buying back two licences of this region. Finally, the Innu Takuaikan Uashat Mak Mani-Utenam community obtained a first licence in 2003 and a second in 2008. In 2011, DFO bought back allocations that were given to Gespeg First Nation and to Viger Meliseet, who already had a fishing licence.

Five First Nations from Quebec and two from New Brunswick have since participated in the Gulf of St. Lawrence shrimp fishery with fishing licences issued under the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations. Through their participation in the commercial fishery and the training programs in place, participating First Nations have the opportunity to increase employment and economic benefits for their community.

Ecocertification

The shrimp industry was the first in eastern Canada to take steps toward certification, helping shrimpers to distinguish their product in the marketplace as higher quality than that of their Asian competitors. The northern shrimp fishery of the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence has been certified sustainable and well managed according to the criteria of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) for the wild capture fishery. Shrimp fishing in fishing areas 9, 10 and 12 (stocks of the Estuary, Sept-Îles, Anticosti Island) obtained certification on September 23, 2008, while that for area 8 (Esquiman stock) was certified on March 30, 2009. Certification was awarded to Quebec, New Brunswick, Newfoundland processing companies.

The shrimp fishery of the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence has been certified for a five year period and the clients have started the certification renewal process in the fall of 2012. The MSC certification has been renewed for another five year in 2014.

A third symposium on the northern shrimp took place on December 10th and 11th, 2012 under the theme, " The northern shrimp of the Gulf of St. Lawrence: The challenges of a responsible fishery". This symposium gathered all the players of the shrimp fishery in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. The symposium aimed at making aware the industry and the general public on the issues and the challenges of this fishery. Furthermore, the issues and the objectives of this fishery for the next years were identified, among others those in connection with the MSC certification.

Mechanical bycatch separator

At the third symposium on northern shrimp in 2012, the recommendation to improve the product's quality was identified and the industry had agreed to work on ways to implement this recommendation. In this context, a prototype for a mechanical bycatch separator was tried by a New Brunswick shrimper whose objective was to assess the possibility of using this type of equipment in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence shrimp fishery. The preliminary results of this test showed that use of this technology had a potential for improving the quality of landed shrimp, although there were still concerns about bycatches and shrimp discards.

Between 2014 and 2016, DFO carried out a pilot project involving six shrimpers from Quebec and New Brunswick chosen by fishers' organizations that used a separator to assess the bycatch separator's effectiveness and to minimize the ergonomic issues of personnel on board. The pilot project results showed that use of a mechanical separator on a larger scale could be considered if monitoring conditions specific to these vessels were implemented.

Processing on board

A shrimper from Quebec started using a new vessel that had on-board processing equipment similar to that which shrimpers in the northern shrimp distant-water fleet (SFAs 0 to 7) use—only smaller—to cook and freeze whole northern shrimp. Until now, no northern shrimp in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence fishing enterprises processed shrimp on board (sorting by size, cooking, and freezing shrimp caught).

After studies and consultations on the project, DFO implemented, for the 2017 season, an adapted approach that takes into account the data management tools in place in the shrimp fishery. These management measures are detailed in the Conservation Harvesting Plan of the northern shrimp. In 2017, only one vessel with processing on board was in service.

1.2 Types of fishing

The only type of northern shrimp fishing authorized in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence is commercial fishing practised with a trawl.

1.3 Participants

The shrimp fishery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence is a limited entry fishery. There are no new licences available. In 2017, 111 fishing licences, including First Nations peoples, were issued for this fishery in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. The table 1 shows the distribution of licence holders on a provincial basis.

| Province | Number of licences | Number of licences First Nations |

|---|---|---|

| Quebec | 39 | 8Footnote 1 |

| New Brunswick | 19 | 2 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 40 | - |

| Prince Edward Island | 2 | - |

| Nova Scotia | 1 | - |

| TOTAL | 111 | |

Source: DFO, Fisheries Management

In 2008, traditional New Brunswick based shrimp harvesters of the Association des crevettiers acadiens du golfe (ACAG) began working on a restructuring plan with intentions of improving the viability of their fishing enterprises. The ACAG identified shrimp fishing enterprises to be bought out and thereafter, working in collaboration with the Province of New Brunswick and DFO representatives, proceeded with the acquisition of these enterprises and with the implementation phase of their plan. By March 2011, this initiative had resulted in 4 Gulf based fishing enterprises having been purchased by 10 traditional Gulf based shrimp harvesters from the ACAG. A new company was created (Corporation 649676 NB Inc.) to manage the allocations acquired with the purchases of licences. This Corporation is owned by 10 traditional shrimp harvesters that are members of ACAG. The goal of the restructuration is to reach the self-sufficiency of the traditional shrimp harvesters of New Brunswick.

As well, in 2008 Fisheries and Oceans Canada implemented enterprise mergers in the Newfoundland and Labrador Region; a voluntary fleet self-rationalization policy which allows most fish harvesters to acquire individual quota (IQ) from an existing enterprise. With the introduction of enterprise mergers the total number of licences are now described as licence shares since the number of licences issued will decrease over time, but the number of licence shares will remain constant.

1.4 Location of the fishery

Five fishing areas were established in the 1970s from known and exploited areas by fishermen. However, the expansion of the fishery in the 1980s challenged some of these boundaries and following a review of data from commercial and scientific activities, a modification of areas was adopted after the 1993 conference in order to better reflect the activities of fish harvesters and the spatial organization of shrimp (Figure 2 ). Four fishing areas were identified from the distribution of all stages of development of the species, including the juveniles and breeding females. Although genetic analyses have not been able to formally identify distinct populations, the four harvest areas that were adopted provide a better link between the shrimp production areas and exploited areas.

The spatial fishing pattern is marked by the exploitation of the bottom located on both sides of the Laurentian Channel and also in the Anticosti and Esquiman channels (Figure 2 ) in depths between 200 and 300 m. This fishing pattern means that shrimp fishery can take place near the coast, for example at approximately 2 nautical miles off the Gaspe coast. The shrimp distribution pattern varies between years. Figure 3 in Section 2.1 presents the Gulf shrimp distribution pattern since the 1990s, according to research surveys.

Figure 2 : Shrimp fishing areas for the Gulf

Source: DFO, Fisheries Management, Quebec Region Fishery Characteristics

Description

This figure shows the 4 shrimp fishing areas in 2017: Estuary (area 12), Sept-Îles (area 10), Anticosti (area 9) and Esquiman (area 8).

1.5 Fishery characteristics

The shrimp fishery usually starts on the first of April and ends in fall. The fishery is carried out using trawlers varying from 16.7 m (55 feet) to 27.4 m (90 feet) in length. A minimum mesh size of 40 mm has been in force since 1986 to minimize the catches of small shrimp and to target the size of shrimp that meets market specifications. Moreover, automatic sorters are not permitted on board the fishing vessels to prevent discards of small shrimp, which would not be counted in catch statistics. In 1993, it was mandated that all fishers use the Nordmore grate to significantly reduce the incidental catches of groundfish.

The implementation of management measures regarding the processing on board that year allowed fishers to use processing equipment aboard their vessels to cook and freeze northern shrimp. This approach being recent, it will be assessed after the fishing season to determine whether any adjustments are needed.

Experimental trap fishing for shrimp was done in the past in the Gulf of St. Lawrence (Gaspésie, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador). The exploratory harvests had disappointing results with low yields.

1.6 Governance

First of all, the fishing activities are subject to the Fisheries Act and its regulations, more specifically the Atlantic Fishery Regulations, 1985 and the Fishery (General) Regulations. Since 2002, the Species at Risk Act has stated rules for endangered and threatened species.

The Management Plan for shrimp in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, including the TAC for each fishing area, is approved by the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard. The Minister takes into account various recommendations including those of the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence Shrimp Advisory Committee (EGSAC). The coordination of EGSAC consultation and management is the responsibility of the Fisheries and Aquaculture Management Branch for the Quebec Region, in collaboration with the two other DFO administrative regions involved in the fishery, the Newfoundland and Labrador Region and the Gulf Region, which includes Prince Edward Island, Eastern New Brunswick and part of Nova Scotia.

The EGSAC is the main mechanism for consultation for the shrimp fishery in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. The committee consists of representatives of shrimp harvesters associations, First Nations, processors, provincial governments and resource managers from DFO. The Department also offers to the Committee the support of resource personnel (an economist, a DFO biologist and an adviser from Conservation and Protection Program).

The EGSAC advises the Minister on issues affecting exploitation of shrimp, including distribution of the resource, methods of exploitation, needs in respect of scientific research and regulatory application, licensing policy and economic analysis of harvesting enterprises.

Beyond the EGSAC, working groups may be formed with specific duties, as needed. Currently, a working group is responsible for monitoring and development of administrative rules related to the Individual Transferable Quota Program for Group B in place since 1993.

Following the 2012 advisory committee, the governance and the structure of the advisory committee have been reviewed and a multi-year management cycle has been implemented. In 2014, new terms of reference of the GSAC have been adopted and are still in effect (Appendix 2)

1.7 Approval process

Development of the IFMP is coordinated by the Resource and Aquaculture Management and Aboriginal Affairs (RAMAA) Direction in Québec. The document drafting and consultation processes involve the Resources Management and Aquaculture division, Strategic Services and Science branch from the Quebec region; the Newfoundland and Labrador and Gulf regions; fishers' organizations; First Nations; the processing industry; and the Atlantic provinces and Quebec. The final draft of the IFMP is approved by the Fisheries Management Regional Director (FMRD), Quebec Region, with the consent of the other regions. The approved IFMP is sent to the fishery stakeholders and to the public.

2. Distribution, scientific and traditional knowledge and stock assessment

2.1 Distribution

There are 25 shrimp species listed in the Estuary and the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence, and the northern shrimp is the most abundant of these by far. The data from the research survey that DFO has conducted in the Estuary and the northern Gulf since 1990 indicate that the northern shrimp is widely distributed in the Estuary and the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence at depths of 150 to 350 m, with over 80% of the cumulative northern shrimp biomass found between 192 and 331 m at bottom temperatures of 3.6 to 5.7 °C (Figure 3 ). The median depth for northern shrimp distribution is 260 m, and the median temperature is 5.2 °C. The survey is deemed to effectively cover the entire distribution range of northern shrimp in the Estuary and the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence. Generally, the northern shrimp is associated with deep water mass and found mainly in channels at depths of 200 to 300 m, where sediment is fine and consolidated. The species occurs only rarely in the southern Gulf.

Figure 3 : Northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) distribution as determined by research surveys from 1990 to 2016

Source: DFO, Sciences, Quebec Region

Description

Figure 3 presents northern shrimp distribution from research surveys from 1990 to 2016 by 5-year period. Dark red hues indicate a high abundance of northern shrimp (in kg / ha) while regions in hues of yellow indicate lower abundance of Greenland halibut (in kg / ha) for the period mentioned in the top left corner.

2.2 Life cycle

The northern shrimp, Pandalus borealis, is a hermaphroditic proterandrous species, which means that individuals first attain male sexual maturity then change sex and become females. This life cycle characteristic is very important for developing harvest strategies and management since the large individuals that are targeted by the fishery are almost exclusively female.

In the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence, shrimp larvae hatch in the spring, in April or May, and remain pelagic for several months. At the end of the summer, the larvae increasingly resemble adults and adopt supra-benthic (associated with the bottom) behaviour. These are then post-larvae or juveniles that are too small to be retained by the trawl nets used in commercial fishing. The juveniles attain male sexual maturity during their second year. Reproduction occurs in the fall and the males can reproduce for two or three years before changing sex. The change of sex occurs in winter at the age of 4 or 5 years at a size of about 21 mm (length of the carapace). The newly transformed females are easily recognizable in the spring and summer commercial catches since they have retained certain male sexual characteristics. These females are called primiparous females and reproduce in the fall (in September or October) after the change of sex. The females carry their fertilized eggs beneath the abdomen during the incubation period which lasts about 8 months. The larvae hatch the following spring. The breeding females that survive reproduction are recognizable from those that have never reproduced and are called multiparous females. Primiparous and multiparous females can in fact be distinguished by morphological characteristics (sternal spines) which disappear when the females perform the prenuptial moult just before mating. The females may reproduce at least twice and the lifespan of shrimp in the Estuary and the Gulf is estimated at about seven years.

2.3 Behavior

Shrimp begin to be caught by commercial trawlers when they are male and have reached a size of about 15 mm carapace length (CL). The likelihood of capture by a trawl increases with size and individuals are fully recruited into the fishery at about 22 mm (CL). The catches of commercial fish harvesters are therefore made up of male and female individuals in proportions that vary depending on the period and place of capture. Migratory movements of shrimp are well known to fish harvesters who have adapted their fishing pattern to take advantage of it. In general, fish harvesters are trying to maintain high catch rates and to maximize the proportion of large shrimp in the catch while minimizing incidental catches of other species.

Shrimp make annual migrations that are related to reproduction. In late fall and early winter the egg-bearing females undertake a migration to shallower areas within their range. In spring, they are gathered on favourable sites for release of the larvae while the males remain spread out throughout the territory. Fish harvesters know how to take advantage of these aggregations of egg-bearing females in spring to obtain high yields. The females moult after the larvae hatch and redistribute into the deeper areas (200-300 m) of the territory. The distribution of shrimp also differs according to the age of the individuals. In general, young shrimp are found in shallower areas, often at the head of the channels, while the older individuals, the females, are found in deeper waters. Concentrations of young shrimp in shallower waters are also greater than those of large shrimp found in deep water. The composition of commercial catches in spring is often a good reflection of this distribution pattern. Since they are taken from shallower water, spring catches often consist of two groups of individuals, egg-bearing females and very small males.

Shrimp also make vertical migrations. They leave the bottom at night to rise in the water column and feed on plankton, then return to the bottom during the day. The extent of vertical migration varies and depends on the stage of development of the individual and local conditions. For example, small shrimp leave the bottom earlier than the females and rise higher in the water column. Fishing yields may be lower at night but the average size of catches should be higher because the proportion of males in the catches is lower. In addition, it can also be advantageous to fish at night to avoid incidental capture of capelin, which also leaves the bottom at night.

The size of females varies along an east-west gradient, the smallest being observed in the Esquiman Channel and the largest in the Estuary. It is interesting to note that since an individual's fertility increases with size, egg production for the same number of females will theoretically be lower towards the east. The number of individuals for a given unit of volume also varies between areas. The number of shrimp per kg depends on the fishing pattern which influences the proportion of males in the catches as well as the average size of females. The number of shrimp per kg increases significantly from west to east since the proportion of males in the commercial catch increases while the size of females decreases.

2.4 Recruitment and growth

Research programs carried out in the field and in the laboratory (in ponds), funded jointly by Group B shrimp fish harvesters and the DFO, have studied the growth of juveniles and adults, while programs for monitoring shrimp populations and the environment have studied the recruitment process.

Females carry the eggs beneath their abdomens for the duration of incubation and the larvae are released in early spring. Laboratory experiments on egg-bearing females have shown that the optimal temperature to ensure good physiological condition of egg-baring females was not the same as for other stages of development (e.g., juveniles, males). A cold temperature seems optimal for maturation and reproduction while a warmer temperature seems to favour survival and growth of larvae and juveniles. In general, an increase in temperature accelerates development of eggs but decreases their survival. Estimates of fertility were obtained from samples from commercial fishing. The fertility of a female of average size was about 2,000 eggs. Mortality of eggs during incubation can be significant and vary from 0 to 86% (14% on average).

Temperatures and the seabed where the females are found determine the duration of incubation and emergence of the larvae can be earlier or later in spring depending on the year or the population. Studies on the processes of recruitment have shown that the length of spring bloom has a positive influence on larval survival. The feeding success of the first larval stages is critical for survival of a cohort. Synchronisation of emergence of larvae with the spring bloom therefore seems to be critical for successful recruitment. In addition, temperature conditions adequate for development and growth of larvae and the zooplankton community (their prey) also appear to be necessary to ensure successful recruitment.

Growth of juveniles, males and females was measured using laboratory experiments at different temperatures. The frequency of moults increases with temperature but decreases with age (or size) of shrimp. Increase in the moult is more significant in young shrimp. The juvenile stage is the stage which is the most sensitive to temperature variations, suggesting that the growth of a cohort is largely influenced by the environmental conditions to which the juveniles are subject. Research programs in the field indicate that growth in winter can be significant and that the change in sex usually occurs between the ages of 4 and 5 years. Experiments in ponds have shown however that the change of sex of a cohort could occur over three years.

2.5 Ecosystem interactions

Variations observed in the physical and biological environment of shrimp have a major effect on population dynamics. Environmental conditions in which the egg-bearing females develop have a direct impact on egg survival and incubation period and most likely on their date of hatching in the spring. Spring conditions at the time of emergence of the larvae have an influence on larval survival and growth. Oceanographic conditions and ecosystem productivity also significantly affect the growth of juveniles. The growth trajectory and strength of cohorts can be maintained during subsequent years until the change of sex and recruitment into the fishery due to the ontogenetic migration of individuals from shallower waters at the lower limit of the intermediate cold layer to deeper waters where the temperature is warmer and more stable.

Deep-water temperatures in the Gulf have been rising for a few years. These waters, which come from outside the Gulf, are a mix of the cold Labrador current and the warm Gulf Stream waters. The ratio of these two water masses is currently richer in warm Gulf Stream water. Waters entering through the Cabot Strait move upstream, mixing little with shallower waters. Overall, the average temperature in the Gulf at depths of 150 m to 300 m reached a record high in 2015, surpassing 6 °C at 250 m and 300 m for the first time since 1915. The area of seafloor with temperatures warmer than 6 °C increased in the Anticosti and Esquiman channels and in the centre of the Gulf, to the detriment of seafloor habitat in the 5 to 6 °C temperature range. In 2015, male and female shrimp were found at bottom temperatures that were 1 °C warmer compared to the 1990 to 2014 average. In Sept-Îles, in the last five years, it has been observed that females mature later in the season and lay their eggs later. However, larval extrusion in the spring does not seem to be affected by this phenomenon, with larval release remaining near late April from year to year.

The ecosystem dominated by groundfish in the early 1990s has progressed to an ecosystem dominated by forage species. Shrimp abundance increased at the same time that abundance of other large-sized groundfish species declined. For a few years now, an increase in the abundance of redfish and cod has been observed in the northern Gulf. Trophic changes may be observed in future years because shrimp are a major dietary component for numerous species.

These changes in environmental and ecosystem conditions observed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence may have an impact on shrimp population dynamics through their effects on such factors as spatial distribution, growth, reproduction and trophic relationships.

In line with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, the DFO promotes responsible fishing aimed at reducing bycatch and mitigating impacts on habitat wherever biologically justifiable and cost effective.

Shrimp fishing is done using small mesh trawls so it is common for the catch to include other species than shrimp. The DFO Policy on Managing Bycatch aims to ensure that Canadian fisheries are managed in a manner that supports the sustainable harvesting of aquatic species by:

- minimizing the risk of fisheries causing serious or irreversible harm to bycatch and discard species,

- accounting for total catch, including bycatch and discards.

Incidental catch in the shrimp fishery were examined from databases of observers at sea. Use of the separating grate since 1993 has significantly reduced incidental catch of certain species of fish. For example, the average incidental catches (between 1999 and 2009) by weight of Greenland halibut were reduced to 13% of what they were in 1991, those of redfish to 2% and those of cod to 0.3%. Now the incidental fish catch are mostly in the range of 1 kg or less per species and per haul sampled. The presence of an observer does not seem to influence the general pattern of fishing since the catch rates of shrimp with and without an observer are similar. In general, the incidental catch for a given species vary between shrimp fishing areas and years. Incidental catch of Greenland halibut, redfish and cod consist of young individuals measuring less than 30 cm for cod and Greenland halibut and less than 20 cm for redfish.

Since 2013, bycatches in the shrimp fishery have risen well above the average, reaching a historic peak of over 1100 tonnes in 2014; they represented 2.6%, 3.6% and 3.3% (in weight) of the northern shrimp catch. This increase is mainly due to a significant rise in small redfish catches.

Bycatch of the most common groundfish species were compared with the results of the research survey in the Estuary and the northern Gulf of St. Lawrence for the same size ranges and years. Bycatch represent less than 1% in number and weight of the survey's abundance and biomass estimates. Catches of pelagic fish and invertebrates cannot be compared to the survey results. For the species that are harvested, there are much fewer bycatches than commercial landings. Bycatches of species that are not harvested can total several tonnes over 17 years. Bycatches of vulnerable species (found in less than 0.25% of the fishing tows) and species at risk (found in 0.4% of the tows) are considered marginal compared to northern Gulf populations because they range from a few specimens to a few hundred kilograms per year. Three taxa are considered vulnerable in accordance with the FAO guidelines in response to UN Resolution 61/105. These are sponges, sea pens and gorgonian corals. Although bycatches in the shrimp fishery are frequent and diversified, they remain low and should not have had an impact on Estuary and northern Gulf populations. Bycatches contribute to an increase in mortality, but this increase is marginal in relation to the normal mortality rates for these populations.

The shrimp trawl used to date in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence is designed to maintain contact with the seafloor throughout a tow. Dragging the foot gear and trawl doors along the seafloor disrupts the substrate, affecting benthic communities and habitats. Canada is also committed, under UN Resolution 61/105, to providing enhanced protection to marine habitats that are particularly sensitive. In compliance with DFO's Policy for Managing the Impact of Fishing on Sensitive Benthic Areas, the likelihood of serious or irreversible damage to benthic areas of biological or ecological importance in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence caused by northern shrimp fishing activities must be assessed based on the information available.

The footprint of shrimp trawling was analyzed by examining the distribution of the cumulative fishing effort since 1982 and from the vessel monitoring system (VMS) since 2012. Shrimp fishing generally takes place at water depths of 200 to 300 m in the Esquiman and Anticosti channels as well as along the two slopes of the Laurentian Channel as far as the Estuary. The traditional fishing grounds are located in areas where surface sediment is fine and consolidated and where natural disturbances have minimal impact. As marine ecosystems, coral beds and sponge grounds are sensitive to bottom trawling due to the sessile nature and low growth rate of these organisms. In the Gulf of St. Lawrence, significant concentrations of sea pens (soft corals) are observed in deep waters in the Laurentian Channel, while sponges are distributed in aggregations throughout the area in question. Benthic communities may also constitute fragile ecosystems in that bottom trawling can reduce their diversity and modify their structure. The great majority of habitats suitable for the establishment of highly diverse benthic communities are found in coastal areas. The cumulative impact of shrimp trawling is likely minimal on sea pen fields and highly diverse benthic communities since the depths targeted for fishing (200–300 m) are not optimal depths for the establishment of sea pen fields (>300 m) or highly diverse benthic communities (<200 m). Since sponge aggregations are found in a wide range of depths, normal fishing activities could alter their distribution. Moreover, significant concentrations of sponges are observed in areas that were intensively fished in the 1980s but where little fishing activity has since been documented. Therefore, sponges appear to have some recovery potential after a period of intensive trawling. With the aim to conserving these ecosystems, fishing closures have been put in place in 2017. See section 7.2 Closing Areas for more detail.

2.6 Stock assessment

Monitoring programs were put in place in the 1980s and 1990s to allow for annual assessment of the fishery and the condition of northern shrimp populations for the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. Data management protocols have also been adopted to ensure that information collected in monitoring programs is adequately captured, validated and archived. Information obtained from the fishery and research surveys are used to make an assessment of the abundance of shrimp as well as to examine various biological characteristics that correspond with the success of the fishery, abundance of stocks or productivity of the resource.

Data from the commercial fishing catch and effort have been collected since 1982 from shrimp harvesters' logbooks, plant purchase receipts and from the dockside landing verification program. Fish harvesters are required to complete a logbook in which the date, place of fishing and number of hours trawled are logged before arriving at dockside. In addition, all landings must be the subject of dockside verification.

Samples of the commercial catch have been taken since 1982. The samples are reported to the laboratory where the species, stage of maturity and size of individuals are recorded.

Collection of information on fishing activities at sea is provided by the program of observers at sea. Detailed information on the target species and on the incidental catch are recorded by observers.

A DFO trawl survey has been conducted each year since 1990 in the Estuary and northern Gulf of St. Lawrence and is designed to assess the abundance of several species including shrimp. A sample of shrimp is taken at each station to determine the species, stage of maturity and size of individuals.

The information on the stock status of the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence is examined during the peer review process and conclusions are presented at the meeting of the Estuary and Gulf Shrimp Advisory Committee. The state of the resource is determined by examining various indicators from the commercial fishery and the research survey. Commercial fishery statistics (shrimp harvesters' catch and effort) are used to estimate fishing effort and to calculate catch rates by weight or number. Samples from the commercial catch enable the number of shrimp harvested to be estimated by size category and by stage of sexual maturity. Biomass indices are calculated using a geostatistical method from data from the annual trawl. Samples from the survey enable the abundance of shrimp to be estimated by size category and by stage of sexual maturity. An index of exploitation rate is obtained by dividing the commercial catch in number by the abundance estimated by the research survey.

In general, catch rates of the commercial fishery and the biomass index from the research survey are consistent and are considered to be good indicators of the shrimp abundance. Abundance indices for males and females are good indicators of the quantity of females that will be available to the fishery and for reproduction in the following year and are, in combination, the main indicator of the condition of stocks. The main indicator for males and females is calculated from summer fishing data (number of units of effort for June, July and August) and data from the survey (abundance). The abundance of primiparous females that will be recruited into the reproductive stock in a given year may in fact be predicted from the abundance of males in the previous year. Similarly, the abundance of reproducing females that release larvae in spring may be predicted from the abundance of females in the previous year.

The assessment of northern shrimp stocks in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence, which is done every two years, is available in the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) section on DFO website.

2.7 Precautionary approach

As a signatory of the United Nations Agreement on Straddling and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (UNFA), Canada has committed to using the Precautionary Approach in managing its stocks. In 2009, the DFO released a policy statement entitled "A fishery decision-making framework incorporating the Precautionary Approach", which details how the Approach could be applied. To be consistent with the Precautionary Approach, fisheries management plans must include resource use strategies that include, on the stock status axis, a Limit Reference Point (LRP) at the Critical: Cautious zone boundary, an Upper Stock Reference Point (USR) at the Cautious: Healthy zone boundary, and a Removal Reference, which defines the maximum catch level in the Healthy zone. The reference points were established by following DFO guidelines from the document entitled: A Fishery Decision Making Framework Incorporating the Precautionary Approach (DFO 2009). Stock status classification zones require determining a limit reference point (LRP) that delimits the critical/cautious zone boundary and an upper stock reference point (USR) that delimits the cautious/healthy zone boundary. The LRP represents the stock status below which serious harm is occurring to the stock. The USR is the stock level threshold below which removals must be progressively reduced in order to avoid reaching the LRP. A third reference point, the target reference point (TRP), can be determined according to broader objectives related to resource productivity or socio-economic factors.

At a peer review process on November 2, 2011, the reference points were determined on the basis of the main stock status indicator. These reference points were used to define a precautionary approach to managing shrimp stocks in the Gulf. Stock status indicators for northern shrimp in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence are updated every year according to the precautionary approach implemented for this fishery.

Reference points were determined using the best information available based on the main stock status indicator. Since northern shrimp change sex, it is important to consider both males (recruitment to the female component) and females (spawning stock) in determining the stock status indicator. The LRP is the minimum level of abundance at which stocks were able to increase even in the presence of predators. However, stock behaviour in the critical zone (abundance lower than the LRP) is uncertain because this level of abundance has not been observed during the period used to determine the reference points. It was proposed to position the USR at a level that determines a sufficiently large cautious zone to allow stocks to respond to management measures that may be implemented. However, the USR value corresponds to stock abundances observed in the absence of predators. If the biomasses of the large groundfish species return to the high values historically observed, it may be necessary to review the USR since it is not certain whether the shrimp stocks could reach abundance levels as high under maximum predation conditions. Finally, it was suggested to establish a TRP at a level higher than the USR because that could allow the implementation of management measures before stocks reach the cautious zone. This target reference point (TRP) could also be adopted based on socioeconomic objectives.

The Figure 4 shows main stock status indicator for each fishing area in 2016

Figure 4 : Main stock status indicator by year and limit (LRP) and upper (USR) stock reference points for each fishing area in 2016

Source: Science, DFO, Quebec Region

Description

Figure 4 shows the evolution of the indicator of the northern shrimp stock status by fishing area between 1982 and 2016. The green line represents the upper reference point, above which the stock is considered in the healthy zone, and the red line represents the limit reference point below which the stock is in the critical zone. When the indicator is found between the green line and the red line, the stock is considered in the caution zone.

2.8 Perspectives

Stock status trends show three periods of increase since 1982. The first two periods of increase likely occurred during periods of low predation mortality. These two periods were characterized by very abundant age classes, which allowed the stocks to increase and remain at relatively high levels. Currently, stock status has been declining for a few years; it approached the upper stock reference and the precautionary area in 2016. The four northern shrimp stocks in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence had remained in the healthy zone since the early 2000s and stock status indicators show a stationary interannual variability since they have been in the healthy zone. The northern shrimp is a species subject to abundance variations related to variable recruitment and changes in environmental and ecosystem conditions. Given its short lifespan and the short period of availability for fishing, frequent adjustments to catch shares are necessary to monitor this stock's dynamics. TAC-based management according to the precautionary approach limits fishing to protect the reproductive potential of the population to help maintain the healthy zone.

3. Economic significance of the fishery

Since the collapse of the groundfish fisheries in the mid-1990s, the crustacean fisheries have constituted a large part of the Quebec and Atlantic Provinces’ maritime fishery (mainly Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick). In these regions, the shrimp fishery is the livelihood of a multitude of workers, both in the primary industry (catch) and in the secondary industry (processing). The northern shrimp primary sector and the processing industry employ a lot of workers in each region. In all, the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence shrimp fishing industry generates close to 2,000 direct jobs.

The shrimp fishery is distinguished from other fisheries by significantly higher operating costs. Shrimp fishing is mainly done using trawlers ranging in length from 55 to 90 feet. Shrimp harvester use mobile gear (bottom trawl) which translates into higher operation, maintenance and boat repair costs. In addition, since this is a fishery that extends over several months, it requires a great deal of fuel. Also, maintaining helper jobs and cost related to boat (docking and insurance) for a long period is another issue.

Shrimp fishing requires on average 3 to 4 crew members (including the captain). The number of crew members on board depends on three main factors: the amount of work, operational safety and product quality. In the fish harvesters’ opinion, it is difficult to reduce labour needs without jeopardizing work safety on board, unless the mechanical bycatch separator is used. In addition, to maintain product quality, the shrimp must be frozen quickly. The amount of work to be done within a short time is significant, especially when catches are abundant. Therefore, shrimp harvesters' labour costs can represent over 25% of operating costs.

3.1 Landings and landed value

Historically, annual northern shrimp landings have almost constantly increased since the mid-1980s. Only in rare years did they decrease. Between 1987 and 2007, landed volume almost tripled, from 12,259 tonnes to 36,407 tonnes—a 197% increase. Since 2010, landings have declined almost constantly, from 36,286 tonnes to 22,477 tonnes in 2017—a 38% decrease, following the example of annual quota decreases that outnumbered increases during that period (Figure 5).

On average, the Quebec Region accounts for about 60% of the shrimp landings in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence. Newfoundland and Labrador and the Gulf and Atlantic regions each account for about 20% of northern shrimp landings.

Although landed volume tripled between 1987 and 2010, the landed value of shrimp barely doubled (Figure 6). Also noted is that landed value varied greatly during that period because of the huge variability in the average landed price (Figure 7), so much so that between 1996 and 2014, landed value ranged between $31M and $57M. In 2015, this landed value increased sharply—by 66%—to $94.5M, a historic record. In 2016, despite a slight decrease, landed value still totalled $88.2M, another historic record slightly below that of 2015. This marked increase in landed value is a direct consequence of the increase in the average landed price in 2015 and 2016 (Figure 7). In 2017, the total value of landings totaled $ 54.4 million, a 38% decrease from 2016, due to a 23% decline in landings combined with a 20% decline in the average landed price.

The five First Nations fleets (six licences) participating in the commercial shrimp fishery have recorded the highest shrimp landings in quantity and value every year. In 2016, they totalled 4292 tonnes for a value of $12.3M or 15% of northern shrimp landed volume and 14% of total northern shrimp landed value. The greatest source of income for First Nations comes from the commercial fishery, followed by the snow crab and lobster fisheries.

Figure 5 : Northern shrimp landed volume (tonnes), by region, 1987–2017p

Source: DFO Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Gulf regions. Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region

Description

Figure 5 presents northern shrimp landings (tonnes) in Quebec, Gulf Region, Newfoundland and the total of these landings between 1987 and 2017p*.

| Quebec (tonnes) |

Gulf Region (tonnes) |

Newfoundland (tonnes) |

Total (tonnes) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 7 714 | 2 295 | 2 295 | 12 304 |

| 1988 | 8 174 | 2 254 | 2 254 | 12 682 |

| 1989 | 9 586 | 2 857 | 2 857 | 15 300 |

| 1990 | 9 636 | 3 640 | 3 640 | 16 916 |

| 1991 | 9 488 | 3 273 | 3 273 | 16 034 |

| 1992 | 8 211 | 2 564 | 2 564 | 13 339 |

| 1993 | 9 562 | 2 371 | 2 371 | 14 304 |

| 1994 | 10 357 | 2 855 | 2 855 | 16 067 |

| 1995 | 10 070 | 3 606 | 3 606 | 17 282 |

| 1996 | 11 929 | 3 982 | 3 982 | 19 893 |

| 1997 | 12 974 | 4 540 | 4 540 | 22 054 |

| 1998 | 15 104 | 5 045 | 5 045 | 25 194 |

| 1999 | 14 917 | 5 100 | 5 100 | 25 117 |

| 2000 | 17 089 | 5 691 | 5 691 | 28 471 |

| 2001 | 12 739 | 6 726 | 6 726 | 26 191 |

| 2002 | 16 550 | 6 893 | 6 893 | 30 336 |

| 2003 | 17 278 | 5 400 | 5 400 | 28 078 |

| 2004 | 22 347 | 6 958 | 6 958 | 36 262 |

| 2005 | 17 422 | 6 419 | 6 419 | 30 259 |

| 2006 | 19 336 | 7 739 | 7 739 | 34 814 |

| 2007 | 18 148 | 8 309 | 8 309 | 34 766 |

| 2008 | 21 617 | 5 970 | 5 970 | 33 556 |

| 2009 | 21 824 | 6 392 | 6 392 | 34 608 |

| 2010 | 22 191 | 6 609 | 6 609 | 35 409 |

| 2011 | 20 318 | 6 318 | 6 318 | 32 953 |

| 2012 | 18 741 | 5 922 | 5 922 | 30 586 |

| 2013 | 20 661 | 5 676 | 5 676 | 32 013 |

| 2014 | 18 298 | 5 759 | 5 759 | 29 816 |

| 2015 | 18 371 | 5 752 | 5 752 | 29 875 |

| 2016 | 16 529 | 5 848 | 5 848 | 28 225 |

| 2017p | 11 698 | 4 458 | 4 458 | 20 614 |

* Preliminary

Figure 6 : Northern shrimp landed value (Millions $), by region, 1987–2017p

Source: DFO Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Gulf regions. Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region

Description

Figure 6 presents northern shrimp landings value (Millions $) in Quebec, Gulf Region, Newfoundland and the total value of these landings between 1987 and 2017p*.

| Quebec (Millions $) |

Gulf Region (Millions $) |

Newfoundland (Millions $) |

Total (Millions $) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 18.4 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 27.4 |

| 1988 | 14.1 | 3.6 | 6.4 | 24.1 |

| 1989 | 13.1 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 21.3 |

| 1990 | 11.6 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 18.8 |

| 1991 | 13.8 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 23.0 |

| 1992 | 12.0 | 3.4 | 2.4 | 17.8 |

| 1993 | 14.5 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 21.0 |

| 1994 | 14.3 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 21.6 |

| 1995 | 17.2 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 27.6 |

| 1996 | 22.3 | 6.5 | 4.4 | 33.2 |

| 1997 | 23.2 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 35.4 |

| 1998 | 23.8 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 37.2 |

| 1999 | 25.0 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 38.7 |

| 2000 | 27.4 | 8.0 | 6.1 | 41.4 |

| 2001 | 16.8 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 31.5 |

| 2002 | 22.0 | 7.9 | 6.8 | 36.7 |

| 2003 | 23.6 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 35.6 |

| 2004 | 29.1 | 7.6 | 6.8 | 43.5 |

| 2005 | 23.9 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 37.7 |

| 2006 | 18.9 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 31.5 |

| 2007 | 18.2 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 35.3 |

| 2008 | 25.3 | 5.8 | 9.0 | 40.1 |

| 2009 | 23.4 | 5.6 | 6.3 | 35.3 |

| 2010 | 24.6 | 6.4 | 8.1 | 39.1 |

| 2011 | 29.9 | 8.3 | 13.2 | 51.4 |

| 2012 | 33.9 | 10.2 | 12.1 | 56.2 |

| 2013 | 31.4 | 7.2 | 8.5 | 47.1 |

| 2014 | 33.7 | 10.2 | 13.1 | 57.1 |

| 2015 | 49.5 | 17.4 | 27.6 | 94.5 |

| 2016 | 48.9 | 16.3 | 23.0 | 88.2 |

| 2017p | 27.6 | 9.3 | 17.5 | 54.4 |

* Preliminary

Figure 7 : Average landed price of Northern shrimp ($/lb), by region, 1987–2017p

Source: DFO Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Gulf regions. Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region

Description

Figure 7 presents the average landed price ($/lb) of northern shrimp in Quebec, Gulf Region and Newfoundland between 1987 and 2017p*.

| Quebec ($/lb) |

Gulf Region ($/lb) |

Newfoundland ($/lb) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 1.08 | 0.99 | 0.79 |

| 1988 | 0.78 | 0.72 | 1.29 |

| 1989 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.74 |

| 1990 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.36 |

| 1991 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.66 |

| 1992 | 0.66 | 0.60 | 0.42 |

| 1993 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.64 |

| 1994 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| 1995 | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.66 |

| 1996 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.50 |

| 1997 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.55 |

| 1998 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.53 |

| 1999 | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.57 |

| 2000 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.49 |

| 2001 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.45 |

| 2002 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| 2003 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.48 |

| 2004 | 0.59 | 0.50 | 0.44 |

| 2005 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.46 |

| 2006 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.35 |

| 2007 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| 2008 | 0.53 | 0.44 | 0.68 |

| 2009 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.45 |

| 2010 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.56 |

| 2011 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.95 |

| 2012 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.92 |

| 2013 | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.68 |

| 2014 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 1.03 |

| 2015 | 1.22 | 1.37 | 2.18 |

| 2016 | 1.34 | 1.26 | 1.78 |

| 2017p | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.78 |

* Preliminary

What explains the sharp increase in the average landed price of shrimp between 2014 and 2016? Answering that question requires turning to the American market because the increase in landed price is a reflection of the sharp increase in the wholesale price of Canadian northern shrimp on the American market. From mid-2014 to 2016, a major upward pressure on Gulf shrimp wholesale prices occurs, itself the result of the combined effect of two factors: lower North American supply of northern shrimp and the weakness of the Canadian dollar against the American dollar.

The decline in the northern shrimp supply in the United States immediately attracts our attention. The status of the northern shrimp biomass in the Gulf of Maine is quite precarious, to the extent that total allowable catches have fallen in recent years. Northern shrimp abundance has reached its lowest level in 30 years. Biologists report that the resource's various recruitment class indices between 2010 and 2012 were widely below the historical average. Consequently, biomass of a size acceptable to the fishery is at its lowest historical level. Between 2009 and 2012, shrimp landings in New England totalled 3300 tonnes per year on average. In 2013, landings totalled a meagre 300 tonnes; since 2014, fisheries have been under a moratorium.

Cooked, peeled northern shrimp from Canada has Europe (Denmark, the United Kingdom) and the United States as its main markets. Northern shrimp prices on the North American market are a good assessment of the species' price trends on world markets.

Canadian landings are not much better because shrimp quotas in the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence and in Newfoundland were on the decline in 2016; northern shrimp quotas in an important area in eastern Newfoundland and Labrador decreased by 40%.

On top of that, northern shrimp supply in Europe was also on the decline in 2015. For the third consecutive year, the total quota for European Union member states fell from 13,396 tonnes in 2014 to 10,900 tonnes in 2015, a 19% decrease. In Greenland (Denmark), the second largest shrimp producer after Canada, the quota decreased by 3% in 2015. In short, this decline in the European northern shrimp supply also contributed to higher northern shrimp prices on the American market.

Lastly, the weakness of the Canadian dollar against the American dollar since 2013 has resulted in an increase in incomes on the American market and, on top of that, an increase on the average landed price paid to shrimpers in Canada.

Shrimp prices are influenced by 1) interaction of world supply of and demand for northern shrimp, and 2) shrimp supply (all species of cold water and warm water shrimp). Shrimp prices on the world market are determined by factors that are beyond the control of Canadian fishers and processors: availability of the resource or global shrimp supply (all species), consumer demand, and exchange rates.

Northern shrimp fishing enterprises' liquid assets fell sharply in the late 2000s. This situation is explained by the marked decrease in average landed price during this period and by the volatility of fuel costs. This fuel cost increase resulted in a major increase in shrimpers' operating costs.3.2 Global shrimp industry

Worldwide production of shrimp (wild and farmed, all species, cold water and warm water) totalled 9 MT in 2016, a 140% increase compared to 1996. This growth is essentially due to the very strong growth of whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) (Figure 8).

Figure 8 : Worldwide shrimp production (wild and farmed), 1996–2016

Source: FAO, FishStat Compilation: Strategic Services, DFO, Quebec Region

Description

Figure 8 presents the worldwide shrimp production (wild and aquaculture) in thousands of tonnes between 1996 and 2016.

| Penaeus monodon (Black Tiger) * (‘000 t) |

Penaeus vannamei (Whiteleg) * (‘000 t) |

Aquaculture Other * (‘000 t) |

Coldwater Shrimp (‘000 t) |

Other Wild (‘000 t) |

Total (‘000 t) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 537 | 150 | 230 | 346 | 2 479 | 3 742 |

| 1997 | 480 | 182 | 265 | 355 | 2 490 | 3 771 |

| 1998 | 503 | 201 | 282 | 382 | 2 562 | 3 930 |

| 1999 | 548 | 194 | 309 | 421 | 2 784 | 4 255 |

| 2000 | 631 | 155 | 352 | 458 | 2 793 | 4 388 |

| 2001 | 673 | 280 | 358 | 428 | 2 682 | 4 421 |

| 2002 | 631 | 488 | 348 | 464 | 2 644 | 4 576 |

| 2003 | 724 | 1 005 | 322 | 433 | 3 184 | 5 668 |

| 2004 | 707 | 1 328 | 329 | 499 | 3 068 | 5 931 |

| 2005 | 665 | 1 678 | 324 | 477 | 2 992 | 6 137 |

| 2006 | 642 | 2 161 | 342 | 455 | 3 143 | 6 744 |

| 2007 | 594 | 2 352 | 350 | 467 | 3 097 | 6 860 |

| 2008 | 720 | 2 305 | 376 | 450 | 2 982 | 6 833 |

| 2009 | 769 | 2 445 | 318 | 405 | 3 034 | 6 971 |

| 2010 | 565 | 2 688 | 377 | 428 | 2 917 | 6 975 |

| 2011 | 691 | 3 089 | 265 | 412 | 3 155 | 7 613 |

| 2012 | 672 | 3 238 | 258 | 389 | 3 225 | 7 782 |

| 2013 | 712 | 3 210 | 319 | 369 | 3 204 | 7 813 |

| 2014 | 705 | 3 697 | 277 | 355 | 3 337 | 8 371 |

| 2015 | 711 | 3 880 | 285 | 356 | 3 376 | 8 608 |

| 2016 | 701 | 4 156 | 324 | 308 | 3 486 | 8 974 |

| Variation 16/96 | 31% | 2667% | 41% | -11% | 41% | 140% |

* Farm Raised Shrimp

Between 1996 and 2016, there was a 2667% increase in farmed whiteleg shrimp. By way of comparison, worldwide catches of wild shrimp increased by 34% during the same period. Canada is the largest northern shrimp producer (cold water wild shrimp), with a 32% market share. Northern shrimp accounts for 16% of shrimp landings in Canada.

The market share of farmed whiteleg shrimp worldwide has not ceased to increase in the past decade. In 1996, it accounted for 4% of worldwide shrimp production. In 2016, 20 years later, it accounted for 46% of worldwide shrimp production. Farmed whiteleg shrimp represented 80% of worldwide aquacultural shrimp production in 2016 whereas Black Tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) accounted for 14% of worldwide aquacultural shrimp production.

In summary, aquacultural shrimp grown in massive quantities in Asia and in South America has an increasingly large share on the world market. Consequently, it directly competes with northern shrimp on its traditional markets (Europe and the United States). In recent years, the worldwide supply of shrimp from southeast Asia has nevertheless declined because of the high mortality of shrimp in the larval or juvenile stages caused by epizootie or early mortality syndrome (EMS). In Thailand, whiteleg shrimp production decreased by 56% between 2011 and 2014. Since 2014, Thai production of whiteleg shrimp has picked up slowly but surely with a total production of 250,000 tonnes in 2014, 300,000 tonnes in 2015 and 300,000 tonnes in 2016. Thai production is expected to increase to 450,000 tonnes over the next two to three years.

4. Management issues

The management issues section provides an overview of the major management issues and issues specific to the Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence shrimp fishery. Management issues for this fishery have been developed according to the fisheries policies and frameworks in place related to the conservation and sustainability of Aboriginal and commercial fisheries. These include the Sustainable Fisheries Framework (SFF), which brings together several frameworks and policies promoting the conservation and the sustainable use of resources, as well as the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy to promote the integration of Firsts Nations communities into fisheries management.

The main issues were identified using three sources of information: the fishery's sustainability profile, the EGSAC's meeting minutes and final reports of MSC's certification.

The Estuary and Gulf of St. Lawrence shrimp fishery was certified by the MSC in 2008 (SFAs 9, 10 and 12) and 2009 (SFA 8). However, at the time, the evaluator determined that the shrimp fishery did not achieve satisfactory results for some of the performance indicators. The fishery obtained a certification renewal in March 2014. Significant progress has been made since the first certification. A framework for the application of a precautionary approach with reference points and TAC adjustment rules has been implemented and has been used since the 2012 fishing season. It has been shown that bycatch are very low and that their impact does not threaten populations of species non-targeted by the fishery or the recovery of at-risk species. In addition, there is a management strategy that minimizes bycatch. The deep waters exploited during fishing correspond to a small proportion of potential habitats. However, the evaluation team has indicated that there was no management strategy in place to ensure that fishing does not cause of damage to benthic communities and habitats.

The performance of fisheries managed by the DFO is evaluated using the Sustainable Survey for Fisheries (SSF). This survey reports on the status of each fish stock, as well as the progress made by the DFO in implementing the SFF which constitutes a series of national policies implemented in order to guide the sustainable management Canadian fisheries. The Sustainability Survey for the northern shrimp fishery identifies habitat and ecosystem issues as well as management weaknesses. These elements explain the need to implement management measures to protect habitats and communities that can be affected by fishery activities. Generally, the Sustainability Survey for the northern shrimp fishery corroborates the results obtained by the MSC certifying team.

Over the years, EGSAC members have identified the management issues requiring concerted action by all stakeholders in the shrimp industry. Tools for monitoring fishing activities are often a topic of discussion. In addition, the changes in terms of quota sharing raise questions about the make-up and governance of the EGSAC.

The following issues are a pooling of all these sources and evaluations. These issues are the challenges to be faced by the fishery's management; they will be used to define the objectives of the integrated fisheries management plan found in Section 5.

4.1 Sustainable exploitation of the shrimp

The northern shrimp fishery is a species which is subject to abundance variations related to recruitment, changes in environmental and ecosystem conditions and natural predation. Management measures are in place in this fishery including a total allowable catch (TAC) to limit the exploitation and protect the spawning potential of the population. The limits on the catch insure that a certain proportion of shrimp, particularly the females, will not be fished and will remain available for the reproduction. However, changes in the physical and biological environment of shrimp have significant effects on population dynamics (see section 4.2). To effectively manage the fisheries, an in-depth understanding of the productivity of the population and community being fished is required. Changes in productivity can have serious consequences on the dynamics of all ecosystems and on the sustainability of fisheries.

4.2 Impacts of the fishery on the ecosystem

In compliance with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, the Fisheries and Oceans Canada promotes responsible fishing aimed at reducing bycatch and mitigating impacts on habitat wherever biologically justifiable and cost effective. The Government of Canada is committed to protecting 5% of Canada’s marine and coastal areas by 2017 and 10% by 2020. The 2020 target is both a domestic target (Canada’s Biodiversity Target 1) and an international target as reflected in the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Aichi Target 11 and the United Nations General Assembly’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development under Goal 14. The 2017 and 2020 targets are collectively referred to as Canada’s marine conservation targets. More information on the background and drivers for Canada’s marine conservation targets is available online.

The DFO is establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and “other effective area-based conservation measures” (OEABCM) in consultation with industry, non-governmental organizations, and other interested parties that help meet these targets. An overview of these tools, including a description of the role of fisheries management measures that qualify as OEABCM, is available online.

Specific measures for the conservation and protection of cold water corals and sponges that affect the northern shrimp fishery qualify as OEABCM and therefore contribute to Canada’s marine conservation targets. More information on these management measures and their conservation objectives is provided in Section 7 (Management measures) of this IFMP.

New policies implemented by the Sustainable Fisheries Framework, including the Policy for Managing the Impact of Fishing on Sensitive Benthic Areas and the Policy on Managing Bycatch, call for consideration of the fishery's impact on the ecosystem. In addition, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) requires protective efforts to ensure recovery of species protected by the Act.Therefore, it is necessary to identify and minimize the negative impact that fishing activities can have on the ecosystem.

4.3 Fishery governance

Over the years, and particularly in recent years, the nature and the number of participants in northern shrimp fishing activities have evolved and changed. The Government of Canada is committed to reconciliation with Aboriginal peoples through renewed Nation-to-Nation, government-to-government and Crown-Inuit relationships, focused on the recognition of rights, respect, cooperation and partnership as the foundation of transformative change. Aboriginal peoples have a special constitutional relationship with the Crown. This relationship, including ancestral and treaty rights, is recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. Section 35 contains a wide range of rights and promises that Aboriginal nations will become partners in Confederation on the basis of a fair and equitable reconciliation between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown. The government recognizes that Aboriginal perspectives and rights must be integrated into all aspects of this relationship.

These changes should be reflected in the governance structure that frames the discussions and recommendations in fishery management. Moreover, pressures and demands from stakeholders who were not traditionally involved in the fishery, such as environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), as well as the industry's hope to maintain the sustainable fishery certification, creates new needs for cooperation within the industry. Finally, the implementation of multi-year management plans is another change for this fishery. In this context, it is essential that governance and the administrative process of the northern shrimp fishery be reviewed.

Variations in the biomass of the various Gulf fisheries resources (Greenland halibut, shrimp, snow crab, lobster and other species) sometimes result in spatio-temporal changes in fleet fishing patterns. This phenomenon sometimes leads to fishing area use conflicts as was the case in the 1990s or more recently since 2010. Therefore, it becomes necessary to implement a collaborative structure in order to document and identify solutions to fishing ground use conflicts.

4.4 Economic prosperity of the fishery