The Gully Marine Protected Area (MPA)

Note:

Charts, diagrams and contact information on this website are provided for information purposes only and should not be used for fishing, navigation or other purposes. Please refer to the MPA Regulations or contact your regional Fisheries and Oceans Canada office for official coordinates.

At-A-Glance

At-A-Glance

The Gully MPA

Dataset for all MPAs available.

Video: The Gully MPA: A Diversity of Life and a Sanctuary for Whales

Location

East of Nova Scotia’s Sable Island; Scotian Shelf Bioregion.

Approximate size (km²) contribution to Marine Conservation Targets

2,363 km²

Approximate % coverage contribution to Marine Conservation Targets

0.04%

Date of Designation

May, 2004

Conservation Objectives

- Minimize harmful impacts from human activities on cetacean populations and their habitats;

- Minimize the disturbance of seafloor habitat and associated benthic communities caused by human activities;

- Maintain and monitor the quality of water and sediments of the Gully; and

- Manage human activities to minimize impacts on other commercial and non-commercial living resources.

Prohibitions

The Gully MPA Regulations prohibit any activities that disturb, damage, destroy or remove living marine organisms or any part of their habitat, unless the activity is listed as an exception in the Regulations or approved by the Minister.

Environmental Context

The Gully is located approximately 200 kilometres off Nova Scotia to the east of Sable Island on the edge of the Scotian Shelf. Over 65 kilometres long and 15 kilometres wide, the Gully is the largest underwater canyon in the western North Atlantic. The movement of glaciers and meltwater erosion formed the canyon approximately 150,000 to 450,000 years ago, when much of the continental shelf was above the current sea level.

The Gully ecosystem encompasses shallow sandy banks, a deep-water canyon environment, and portions of the continental slope and abyssal plain, providing habitat for a wide diversity of species. The Gully’s size, shape, and location have an effect on currents and local circulation patterns, concentrating nutrients and small organisms within the canyon.

The Gully is home to the endangered Scotian Shelf population of Northern bottlenose whales and is an important habitat for 15 other species of whales and dolphins. Tiny plankton, a variety of fish such as sharks, tunas and swordfish, and seabirds inhabit surface waters, while halibut, skates, white hake and lanternfish can be found as deep as one kilometre. The ocean floor supports crabs, sea pens, anemones, brittle stars, and approximately 30 species of cold-water corals.

Ecosystem

Ecosystem

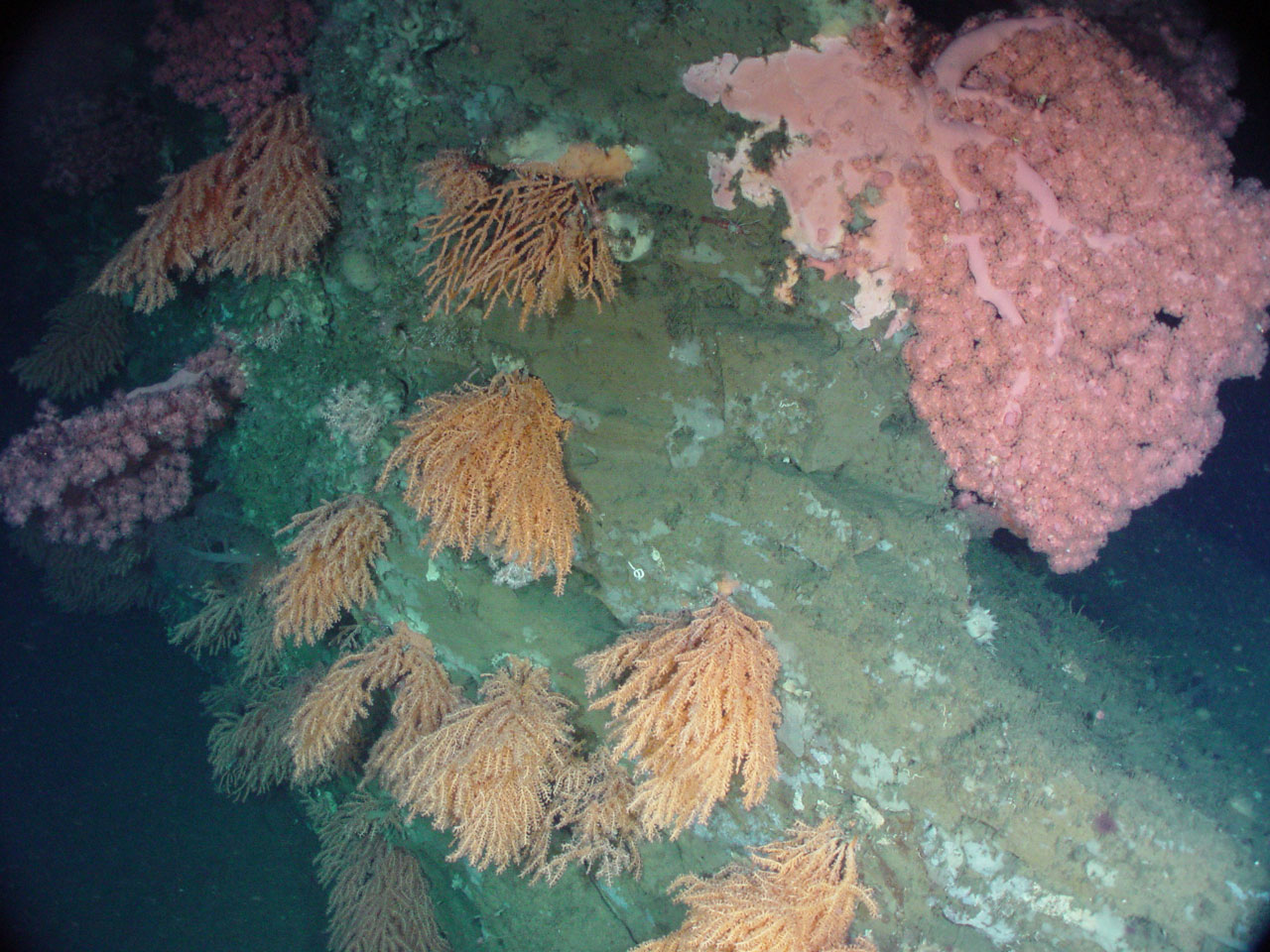

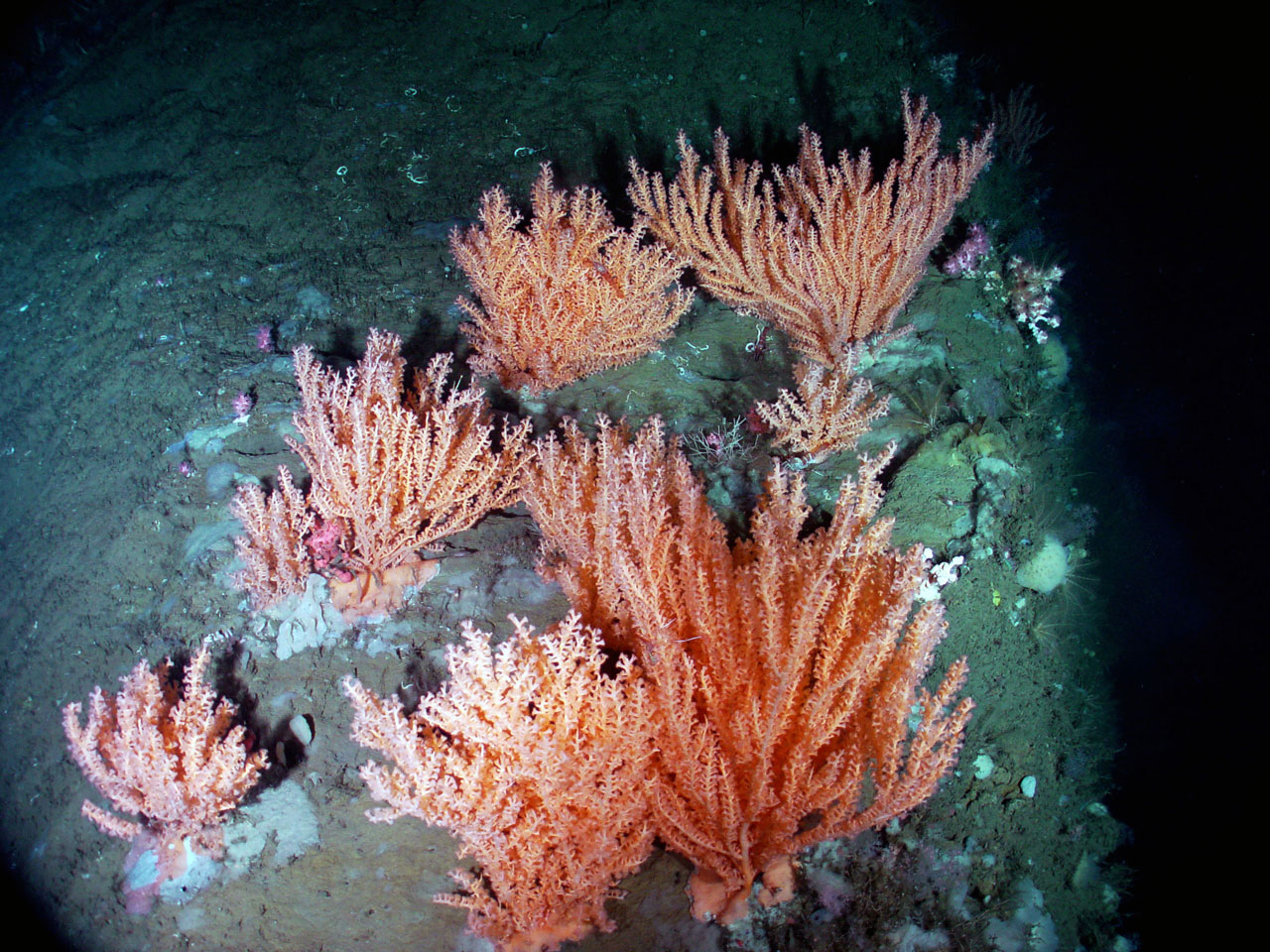

Deep-sea coral

The Gully is a deep submarine canyon formed by a combination of river flow, glacial ice and glacial meltwater erosion. This process occurred several hundred thousand years ago. Repeated glaciation events are thought to be the dominant processes that created this deep-water canyon.

The Gully ecosystem encompasses shallow sandy banks, a deep-water canyon environment, and portions of the continental slope and abyssal plain. This area, provides habitat for a wide diversity of species. Water circulation patterns and hydrography strongly influence the distribution of nutrients along the canyon and can fuel primary productivity, (a process where inorganic substances are synthesized by organisms to produce simple organic materials) in the Gully.

The region around the Gully also supports a number of commercial fisheries and was once of interest to the oil and gas industry.

This marine protected area is a hotspot for whales, dolphins and porpoises and an important habitat for both migratory and resident cetacean species, including the endangered Scotian Shelf population of northern bottlenose whale. Several northern bottlenose whale individuals are year-round residents of the Gully, while others move between the Gully and neighbouring canyons. These toothed whales are known to dive from the surface waters to deep parts of the canyon, sometimes staying underwater for over an hour in search of deep-water squid and other prey.

Surface waters and subsurface waters of the Gully are home to tiny plankton, a variety of fish such as sharks, tunas and swordfish, and as well as seabirds. Halibut, skates, white hake and lanternfish can be found as deep as 1 kilometre below the surface. The ocean floor supports crabs, sea pens, anemones, brittle stars, and the highest known variety of cold-water corals in Atlantic Canada, with approximately 30 species identified to date. Cold-water corals cling to boulders along the slopes of the canyon.

Even after decades of research in the Gully, many mysteries remain, making it a place of great interest for continued research, monitoring, and conservation efforts.

Underwater habitat of the Gully.

Management and Conservation

Management and Conservation

Managing the Gully

The Gully MPA Management Plan (2017) supports the MPA Regulations and provides guidance to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), marine users, the public and other regulators on protecting and managing the Gully’s ecosystem. Conservation priorities for the Gully include:

- Protecting whales and dolphins from the impacts of human activities

- Protecting seafloor communities and habitat from alterations caused by human activities

- Maintaining or restoring the quality of the water and sediments of the canyon

- Protecting aquatic species

What does DFO do to protect the Gully’s ecosystem?

- Ecosystem Monitoring: DFO monitors the Gully and collects and analyzes data.

- Monitoring of Human Activities: Shipping, fishing, research, tourism, and potential oil and gas activities occurring in and around the Gully MPA are regularly monitored and analyzed to ensure human use of the area remains compatible with the conservation objectives of the MPA.

- Compliance Promotion: Activities to promote compliance include development of best practice guidelines, recognition and adoption of industry codes of practice, and promotion and development of stewardship initiatives. For example, DFO has worked with the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board (CNSOPB) to develop protocols and policies to help guide the environmental assessment and operation of oil and gas activities that may have an impact on the Gully.

- Education and Outreach: ongoing efforts to promote the Gully MPA have included speaking engagements at schools, museums, national and international conferences, the development of a range of educational materials such as videos, displays at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, a brochure, and even a Gully colouring book!

- Gully MPA Activity Approvals: DFO permits research, monitoring and educational activities in the MPA provided they are consistent with the conservation objectives and do not cause unjustifiable disturbance, damage, destruction or removal of Gully ecosystem components. Learn more about applying for an activity plan to conduct an activity in the Gully MPA.

- Evaluation and Reporting: A review of Gully MPA management was conducted to measure DFO’s progress towards meeting the commitments laid out in the Gully MPA management plan and other Oceans Act MPA program guidance and policies. The findings were released in 2012 and were used to inform the review and revision of the Gully Management Plan.

Surveillance and Enforcement

DFO is the lead federal authority for the Gully. This means that DFO must ensure that regulations and conservation measures are respected and enforced. The department is responsible for enforcing the acts and regulations of the Oceans Act, the Fisheries Act, and the Species at Risk Act. There is also other legislation considered for fisheries conservation, environmental protection, habitat protection, and marine safety. For example, Transport Canada enforces the Canada Shipping Act. This Act governs the safety of marine transport and recreational boating, as well pollution prevention to protect the marine environment.

Conservation and Protection’s surveillance aircraft

Surveillance activities include aerial patrols as well as well as remote surveillance. Remote surveillance tools such as vessel monitoring systems (VMS) can be used to monitor fishing vessel activity. Fisheries information is also collected from other sources such as observer reports and fishing logbooks. Analysts then compile this information to produce intelligence on vessel activities. In addition, DFO collaborates with other federal government departments such as Transport Canada and the Department of National Defence to ensure proper surveillance and enforcement in the MPA.

Conservation Milestones

Conservation interest in the Gully has grown considerably over the last several decades. Government agencies, researchers, marine industries and conservationists have taken significant steps, as listed below, to recognize and protect this unique canyon.

- 1988

- The northern bottlenose whales of the Gully became the focus of research by Dalhousie University scientists.

- 1990

- Oil and gas proponents established a tanker exclusion zone around Sable Island and the Gully.

- 1992

- Parks Canada selected an area encompassing the Gully and Sable Island as a Natural Area of Canadian Significance.

- 1994

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) designated the Gully Whale Sanctuary to reduce ship collisions and limit noise disturbance.

- Canadian Wildlife Service workshop discussed the need for a conservation strategy for the Gully.

- 1996

- The population of northern bottlenose whales found in the Gully was assessed as "vulnerable" by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

- 1997

- The Environmental Impact Statement for the Sable Offshore Energy Project, west of the Gully, identified the canyon as a 'unique ecological site' and 'valued ecosystem component'.

- 1998

- The Sable Gully Conservation Strategy was released, including goals and recommendations for planning and management.

- The Gully was announced as an Area of Interest (AOI) for consideration as an Oceans Act MPA.

- 1998-99

- ExxonMobil Canada drafted The Gully Code of Practice as part of its Environmental Protection Plan for the Sable Offshore Energy Project.

- 1999

- The Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board adopted a Gully Policy stating that no new oil and gas activity would be permitted in the Gully AOI.

- 1999-2004

- Public consultation was conducted to get feedback on the MPA design and proposed regulations.

- 2002

- The population of northern bottlenose whales found in the Gully was reassessed as "endangered" by COSEWIC.

- 2003

- The Gully Advisory Committee was established.

- 2004

- The final Gully MPA Regulations were published and the Gully MPA was designated.

- 2006

- The population of northern bottlenose whales found in the Gully was listed as "endangered" under the Species at Risk Act.

- 2008

- The Gully MPA Management Plan was published.

- 2010

- A framework of indicators for monitoring the Gully ecosystem was drafted.

- The Recovery Strategy for the endangered population of northern bottlenose whales found in the Gully was posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry.

- 2012

- A workshop was held to review existing data, protocols, and procedures for Gully ecosystem monitoring.

- 2014

- Ten year anniversary of the designation of the Gully as a MPA. A Progress Report is available that provides the management and research highlights over the last decade.

- The Gully MPA: 10 years of progress

- 2017

- The second edition of the Gully MPA Management Plan was published.

- Mission to the Gully permanent exhibit opens at the Museum of Natural History in Halifax. The exhibit simulates being aboard a multi-disciplinary research vessel above the Gully canyon.

- 2021

-

A Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) workshop was held to review and update existing data, protocols, and procedures for Gully ecosystem monitoring.

- 2022

- A Science Advisory Report was published regarding the 2021 Review of Baseline Information, Monitoring Indicators, and Trends in the Gully MPA. This report was published following the CSAS workshop held in 2021.

New protection measures

Video camera surveys that took place over several years, revealed abundant deep-sea corals in Zone 2. This discovery triggered an adaptive management response. The original zoning for the MPA allowed groundfish fishing in these areas; an activity that can harm deep-sea corals. Therefore, in 2019, DFO introduced additional protection measures for the seafloor in order to protect corals in this area. The Comprehensive Protection Zone (Zone 1) was expanded under the Fisheries Act, as bottom fishing was restricted from two small areas in Zone 2. These new protection measures prohibit groundfish harvesting in these areas, in order to meet the conservation objective of protecting seafloor communities and habitat from impacts caused by human activities.

The closures to groundfish harvesting include:

Portion of 4VS:

The portion of Division 4VS enclosed by rhumb lines joining the following points in the order in which they are listed:

| POINT | LATITUDE | LONGITUDE |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 43°53'13”N | 58°51'52”W |

| 2. | 43°52'55”N | 58°48'00”W |

| 3. | 43°52'07”N | 58°50'45”W |

| 4. | 43°50'52”N | 58°51'51”W |

| 5. | 43°53'13”N | 58°51'52”W |

Portion of 4W:

The portion of Division 4W enclosed by rhumb lines joining the following points in the order in which they are listed:

| POINT | LATITUDE | LONGITUDE |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 43°59'36”N | 59°03'51”W |

| 2. | 43°58'56”N | 59°00'27”W |

| 3. | 43°58'56”N | 59°02'40”W |

| 4. | 43°57'53”N | 59°01'13”W |

| 5. | 43°58'34”N | 59°03'12”W |

| 6. | 43°59'25”N | 59°05'33”W |

| 7. | 43°59'36”N | 59°03'51”W |

Coordinates are expressed using the North American Datum 1983 (NAD83) geodetic reference system.

Research and Monitoring

Research and Monitoring

Decades of scientific activity in the Gully were foundational in its designation as an MPA. These activities continue in the MPA and they play a critical role in its management. Research increases our understanding of the physical, chemical and biological processes important for the Gully MPA. Research also contributes to our knowledge of the human history and socio-economic importance of the MPA. Monitoring is conducted to provide managers with accurate and timely information on the state of the ecosystem and related threats which can trigger management changes.

Research and monitoring efforts in the Gully MPA are collective and involve universities, government agencies, industry and non-government organizations. Researchers are encouraged to communicate the results of their MPA work to a broad audience including the Canadian public and the international community. Here we profile some of the research and monitoring efforts that have occurred in the Gully. To learn more about these and other scientific undertakings, see our list of publications.

Foundation Science

When the Gully was being assessed as an MPA candidate, DFO coordinated a compilation of existing knowledge. The resulting Science Review was published as a Research Document and summarized in a Habitat Status Report, both in 1998. Some information gaps were filled by research projects conducted at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography between 1999 and 2001. These and other ongoing studies confirmed the Gully’s significance as a diverse and highly productive ecosystem with a remarkable variety of habitats for fish, mammals, seabirds and bottom dwellers. The Gully Ecosystem report captured the state of knowledge in 2002 and made the case for special protection under Canada’s Oceans Act.

Seabed Mapping

The Canadian Hydrographic Service and the Geological Survey of Canada completed multibeam surveys in the Gully between 1996 and 2006. Recent surveys were completed in 2023. In total, depth measurements have been collected for about 90% of the MPA. Three map sheets were produced to reveal the true size as well as the shape of the canyon and are available for download. For additional information on Gully maps and their applications, see a brief habitat mapping profile.

Source: Improved Seafloor Maps and The Gully.

Oceanography

Scientists at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography have studied the properties of seawater in the Gully for decades. A lot has been learned about circulation patterns, chemistry, nutrients, microbes and plankton. Water properties are now sampled twice a year in the spring and fall at fixed stations in the MPA during the Atlantic Zone Monitoring Program. In addition to these ship-based measurements, water column data for temperature, salinity and current were collected by using a water sampling device. This baseline data could be used to show trends and changing conditions over time and may be useful when considering effects of climate change.

A Conductivity Temperature Depth (CTD) rosette (water sampling device) being deployed

Benthic Research

Marine scientists started documenting seabed organisms in the Gully as early as the 1880s when deep-water coral catches were common in the offshore fishery. Contemporary Benthic ecologists study seabed communities using underwater cameras, seabed sediment grabs, acoustic receivers, specimen sampling and water characteristics, including temperature and salinity. Research is carried out by various groups including DFO, universities, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and more. Access to sophisticated underwater vehicles like ROPOS (Remotely Operated Platform for Ocean Sciences) has extended optical surveys and specimen sampling to canyon depths reaching 2.5 kilometres. The MPA also features in Oasis of the Deep: Cold Water Corals of Atlantic Canada.

Okeanos Explorer ROV

In 2019, as part of a larger expedition to explore Atlantic canyons and seamounts, U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) vessel Okeanos Explorer conducted a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive in Zone 1 of the Gully MPA. Reaching a depth of 1,350 m, the ROV dive occurred on the eastern wall of the Gully canyon. It was the first time this area was surveyed by submersible.

A high abundance of bamboo corals (Keratoisis sp.) were observed. Several corals were observed, which were not previously described in the region. During the dive, video, photographs, oceanographic data (e.g., temperature, depth, conductivity, dissolved oxygen, turbidity, etc.) and 5 biological samples were collected. Video footage from the dive was live streamed and included scientists discussing what was being observed. See video highlights from the dive.

Animal Tracking

In September 2021, a line of acoustic receivers was deployed in Zone 2 of the Gully MPA. These sensor packages were configured by DFO scientists in collaboration with Ocean Tracking Network at Dalhousie University. Fish, invertebrates and mammals tagged with miniature acoustic transmitters will be detected as they pass the line of receivers.

DFO scientists are especially interested in monitoring Atlantic halibut. Receivers in the Gully will help assess whether halibut migrate from the juvenile hotspot to the north of the MPA to utilize habitats in the MPA. See more information about the Ocean Tracking Network.

Whale Studies

In 1988, researchers in the Biology Department at Dalhousie University began studying whales in the Gully. The resident population of endangered Scotian Shelf Northern bottlenose whales have been the focus of much of the research in the MPA, though data is collected on many cetacean species that regularly use the canyon. Academic and government scientists monitor the occurrence, habitat use, population trends, and behaviour of cetaceans using a variety of methods such as vessel-based surveys, photo-identification techniques and passive acoustic monitoring (PAM). Since 2012, DFO Maritimes has maintained a PAM site within the Gully, and datasets collected from this site represent the longest acoustic timeseries available for Atlantic Canada. Analysis of this acoustic data has revealed that several baleen and toothed whale species regularly occur in the Gully throughout the year. This includes at-risk whales such as blue, fin, northern bottlenose, Sowerby’s beaked whales, sei, humpback, sperm and Cuvier’s beaked whales. These studies demonstrate that the Gully is an important feeding area for northern bottlenose and Sowerby’s beaked whales.

Researchers collecting data on Northern Bottlenose whales in the Gully. © Northern Bottlenose Whale Project, Dalhousie University

Multispecies Bottom Trawl Surveys

Government research vessels have undertaken trawl surveys in the Gully for more than 50 years as part of a region-wide fish and invertebrate monitoring program. Everything caught in the trawl is identified, weighed and measured. Sex, age and condition are recorded and stomachs are routinely collected for prey analysis. Additional tissue samples support genetic and contaminant studies. This information contributes to the regional DFO fish stock assessments and is an essential monitoring tool for the health of the ecosystems. The industry-DFO halibut longline survey occurs yearly. It provides a primary index of exploitable biomass for the assessment of the Atlantic Halibut and is a platform for other halibut science. The survey also provides important information for MPA monitoring relative to abundance, size distribution and diversity of selected longline-valuable species in the Gully.

Multispecies Pelagic Trawl Surveys

Beginning in 2007, scientists made several trips to study the animals living in the water column of the Gully. Samples were taken from the surface to 2,380 metres deep using a midwater trawl with a 60 square-metre mouth opening. These were the first deep, mid-water surveys in over twenty years in this part of the Atlantic and some of the first globally to sample at such depths within a canyon. Catches were dominated by small non-commercial species such as lanternfish and krill. Juvenile and adult squid were also collected among the 500-plus species sampled.

Seabird Surveys

The Canadian Wildlife Service places biologists on research vessels to survey birds on the open ocean. Many scientific expeditions to the Gully have benefitted from having a seabird specialist aboard. Observers with the Eastern Canada Seabirds at Sea program keep watch in the wheelhouse and follow a monitoring protocol while at sea. Visual scans for birds are also conducted when vessels are stopped or station keeping. Since 2006, over 1500 kilometres have been surveyed in the MPA. The data shows that 24 bird species are present in the MPA. Observations confirm that the Gully is an important offshore feeding area in Atlantic Canada.

Monitoring Contaminants and Debris

Government, industry and academic sampling programs have targeted various components of the Gully ecosystem over the years. Water samples, sediment grabs and animal tissues have been examined for a variety of chemicals. The Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat hosted a series of workshops to examine the potential risks. That process resulted in a Research Document and a Science Advisory Report addressing the state of knowledge and monitoring needs. Surveys of floating debris in the MPA have been taking place since the 1990s. In 2023, a study on floating plastic pollution was published. Researchers investigated trends in the quantity and composition of plastics over time and compared them to the stomach contents of stranded northern bottlenose whales.

Ecosystem Monitoring

Monitoring a range of indicators and threats is necessary to ensure the MPA is meeting its stated conservation objectives. A recommended approach to ecosystem monitoring was published by the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat in 2010. A suite of indicators, strategies and protocols were examined. 29 indicators were recommended for monitoring the ecosystem and an additional 18 were advanced for pressure monitoring. In 2021, a review of these monitoring indicators were presented in a Research Document, along with an evaluation of baseline information and trends observed within the MPA. These indicators will be reviewed regularly to evaluate trends, including those connected to climate change.

Vessel Traffic Monitoring

Threats posed by shipping activities have been a longstanding concern for management of the MPA. The remote offshore location of the Gully has made monitoring a particular challenge. Monitoring and surveillance is conducted in partnership with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Coast Guard and Transport Canada through ship and aerial patrols. Due to the offshore location, it takes a great deal of time and resources to visit the site, therefore remote monitoring tools such as vessel monitoring systems(VMS) are used. Aerial patrols have been supplemented in recent years by mandatory ballast water exchange (the replacement of water in a ballast tank of the ship by dumping and replacing it with surrounding water), reporting and positional data collected from satellites. A report of vessel traffic in Atlantic Canada presents monthly maps and statistics for Gully transits. Additionally, the 2023 pressure monitoring report provides an overview of vessel traffic in the Gully MPA. The report includes the number, average speed and types of vessels that transit through this area.

Environmental DNA (eDNA)

Since 2018, scientists at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography have been using environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling as a non-invasive method to monitor biodiversity. This approach leverages the ability to capture, extract, and sequence free-floating DNA from water. The water sampling is also part of the Atlantic Zone Monitoring Program (AZMP). Pilot studies, in both the inshore and offshore environments, have underscored the effectiveness of eDNA in measuring biodiversity patterns and enhancing existing sampling methods. Regular eDNA sampling is currently underway in the Gully as part of a standardized biomonitoring program for MPAs in the bioregion. eDNA is helping us understand the ecosystem in the Gully, at different depths.

Okeanos Explorer

In 2019, U.S National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) vessel Okeanos Explorer conducted a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive in Zone 1 of the Gully MPA.

Reaching a depth of 1,350 m, the ROV dive occurred on the eastern wall of the Gully canyon, and was the first time this area was surveyed by a submersible. A high abundance of bamboo corals (Keratoisis sp.) were observed as well as several corals that were not previously known in this region. During the dive, video, photographs, oceanographic data, and biological samples were collected. Video footage from the dive was live streamed and included scientists discussing their observations.

Animal Tracking

In September 2021, a line of acoustic receivers was deployed in Zone 2 of the Gully. These receivers were configured by DFO scientists in collaboration with the Ocean Tracking Network (OTN) at Dalhousie University. Fish, invertebrates and mammals tagged with miniature acoustic transmitters will be detected as they pass the line of underwater receivers. DFO scientists are monitoring Atlantic halibut and the receivers in the Gully will help them assess migration patterns of this species.

Regulations

Regulations

In May 2004, regulations were enacted to formally designate the Gully MPA, and provide legal protection for the canyon ecosystem.

The Gully MPA Regulations establish the boundary and management zones. The MPA is 2,364 square kilometres, and is divided into three management zones.

- Zone 1 encompasses the deep canyon environment, which includes important habitat for cold-water corals, dolphins and whales. This zone is very sensitive to human impacts and has the highest level of protection.

- Zone 2 includes the canyon head and sides, feeder canyons and the continental slope. This area contains a high diversity of marine life, and has a high level of protection with a limited number of permitted activities.

- Zone 3 includes the sand banks adjacent to the canyon, which are prone to regular natural disturbance. The natural variability of the ecosystem in this zone provides management with some flexibility to permit more activities, provided they do not damage or destroy species assemblages or their habitats.

The Gully MPA Regulations make it an offence for any person to:

disturb, damage or destroy in the Gully MPA, or remove from it, any living marine organism or any part of its habitat [sec. 4(a)].

These general prohibitions apply to the entire water column and include the seabed to a depth of 15 metres. The Gully is connected with the broader Scotian Shelf ecosystem via currents and movements of marine organisms. As such, the Regulations also prohibit activities in the vicinity of the MPA that result in the disturbance, damage, destruction or removal of organisms or habitats within the Gully MPA. The Regulations identify certain activities that are permitted in the MPA provided they operate under relevant legal conditions. These are:

- Commercial hook-and-line fishing for halibut, tuna, shark and swordfish in Zones 2 and 3

- Vessel transit (in compliance with the Canada Shipping Act)

- Search and rescue, environmental emergency response and clean up

- Activities related to national security, sovereignty and public safety

Accidents

As per section 7 of the Gully MPA regulations, any person involved in an accident that is likely to result in any disturbance, damage, destruction or removal in the MPA of any living marine organism or any part of its habitat; must, within two hours after its occurrence, report the accident to the Canadian Coast Guard (1 (800) 565-1633). In addition, a description of all environmental emergencies and other incidents should be submitted to DFO using a standardized reporting template as soon as possible after the incident.

Violations

Violations of MPA Regulations can carry penalties of up to $100,000 for an offence punishable on summary conviction, and up to $500,000 for an indictable offence. A conviction may result in additional fines and imprisonment. Violations may also result in charges under the Fisheries Act and other applicable legislation, such as the Shipping Act and the Species at Risk Act. Convictions can result in fines and imprisonment under these Acts.

Critical Habitat

In 2010, Zone 1 of the Gully MPA was legally declared under the Species at Risk Act as Critical Habitat for the endangered Scotian Shelf population of Northern bottlenose whales.

Activity Application

Activity Application

Certain activities are allowed in the Gully MPA if a proponent submits an activity plan to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and it receives Ministerial approval.

Foreign researchers interested in conducting marine scientific research within waters under Canadian jurisdiction must request approval by writing directly to Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada. The request is then evaluated for approval under Canada’s Foreign Vessel Clearance Request process. DFO reviews research requests as they relate to the Department’s mandate for marine science, resource management and conservation. In cases where research requests involve the Gully MPA, DFO reviews the proposed activities against the conservation and management objectives of the site.

Publications

Publications

Monitoring human impacts

- Contaminant Monitoring in the Gully Marine Protected Area. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. Science Advisory Report 2009/002: 15 p.

- DFO. 2009. Proceedings of a Maritimes Science Advisory Process to Develop a Framework for Monitoring of Contaminants in the Gully Marine Protected Area: Part 1 - Data Inputs; 11 December 2007 Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Proceedings Series 2009/018: iv + 18 p.

- McConney, L., Wingfield, J., Rozalska, K., Schram, C., Pardy, G., Will, E., Feyrer, L., and Whitehead, H. 2023. The current state of pressure monitoring in the Gully Marine Protected Area. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 3563: xi + 113 p.

- McQuinn, I.H. and D. Carrier. 2005, Far-field Measurements of Seismic Airgun Array Pulses in the Nova Scotia Gully Marine Protected Area. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2615: v + 20 p.

- Ocean Bottom Acoustic Observations in the Scotian Shelf Gully During an Exploration Seismic Survey – A Detailed Study. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2747: viii + 73 p.

- Yeats, P., J. Hellou, T. King, and B. Law. 2009. Measurements of Chemical Contaminants and Toxicological Effects in the Gully. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Research Document 2008/066: iv + 21 p.

Marine geology

- Cameron, G.D.M. and E.L. King. 2008a. Seafloor-slope analysis, The Gully, Scotian Shelf, offshore Eastern Canada. Geological Survey of Canada, Map 2121A, scale 1:100000.

- Cameron, G.D.M. and E.L. King. 2008b. Sun-illuminated seafloor topography, The Gully, Scotian Shelf, offshore Eastern Canada. Geological Survey of Canada, Map 2122A, scale 1:100000.

- Cameron, G.D.M., E.L. King and D.C. Campbell. 2008. Surficial geology and sun-illuminated seafloor topography, The Gully, Scotian Shelf, offshore Eastern Canada. Geological Survey of Canada, Map 2123A, scale 1:100000. Cochrane, N. A. 2007.

- Fader, G. 2003. The Mineral Potential of The Gully Marine Protected Area, A Submarine Canyon of the Outer Scotian Shelf. With Contributions from Edward L. King. Geological Survey of Canada Open File 1634.

Fishes

- Breeze, H. 2002. Commercial fisheries of the Sable Gully and surrounding region: Historical and present activities. Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2612: vii + 83 p. DFO. 2009.

- Kenchington, T.J., Themelis, D.E., DeVaney, S.C., and Kenchington, E.L. 2020. The meso- and bathypelagic fishes in a large submarine canyon: Assemblage structure of the principal species in the Gully Marine Protected Area. Frontiers in Marine Science 7(181).

- Kenchington, T.J., Themelis, D.E., DeVaney, S.C., and Pietsch, T.W. 2020. Pelagic anglerfishes (Lophiiformes: Ceratioidei) of the Gully Marine Protected Area. Marine Biology Research 16(4): 265-279.

- Kenchington, T.J., M. Best, C. Bourbonnais-Boyce, P. Clement, A. Cogswell, B. MacDonald, W.J. MacEachern, K. MacIsaac, P. MacNab, L. Paon, J. Reid, S. Roach, L. Shea, D. Themelis and E.L.R. Kenchington. 2009. Methodology of the 2007 Survey of Meso- and Bathypelagic Micronekton of the Sable Gully: Cruise TEM768. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2853: vi + 91 p.

- Sameoto, D., N. Cochrane and M. Kennedy. 2002. Seasonal abundance, vertical and geographic distribution of mesozooplankton, macrozooplankton and micronekton in the Gully and the western Scotian Shelf (1999-2000). Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2427. v + 37 p.

Cetaceans

- DFO. 2022. Threat assessment for Northern Bottlenose Whales off eastern Canada. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2022/032.

- DFO. 2020. Action Plan for the Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus), Northwest Atlantic Population, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. iv + 23 pp.

- DFO. 2018. Identification of habitats important to the blue whale in the western North Atlantic. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2018/003.DFO. 2017. Management Plan for the Sowerby's Beaked Whale (Mesoplodon bidens) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. iv + 46 pp.

- DFO. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the Northern Bottlenose Whale, Scotian Shelf population, in Atlantic Canadian Waters. .Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada. vi + 61p.

- Feyrer, L. J., Stanistreet, J. E., Gomez, C., Adams, M., Lawson, J. S., Ferguson, S. H., Heaslip, S. G., Lefort, K. J., Davidson, E. A., Hussey, N. E., Whitehead, H., & Moors‐Murphy, H. (2024). Identifying important habitat for northern bottlenose and Sowerby's beaked whales in the western North Atlantic. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.4064

- Gosselin, J.F. and J. Lawson. 2004. Distribution and abundance indices of marine mammals in the Gully and two adjacent canyons of the Scotian Shelf before and during nearby hydrocarbon seismic exploration programmes in April and July 2003. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2004/133: ii + 24 p.

- Hooker, S.K., T.L. Metcalfe, C.D. Metcalfe, C.M. Angell, J.Y. Wilson, M.J. Moore and H. Whitehead. 2008. Changes in persistent contaminant concentration and CYP1A1 protein expression in biopsy samples from northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus, following the onset of nearby oil and gas development. Environmental Pollution 152: 205-216.

- Hooker, S.K., H. Whitehead and S. Gowan. 1999. Marine protected area design and the spatial and temporal distribution of cetaceans in a submarine canyon. Conservation Biology 13(3): 592-602.

- Kelly, N.E., Feyrer, L., Gavel, H., Trela, O., Ledwell, W., Breeze, H., Marotte, E.C., McConney, L., and Whitehead, H. 2023. Long term trends in floating plastic pollution within a marine protected area identifies threats for endangered northern bottlenose whales. Environ. Res.: 115686.

- Lee, K., H. Bain, and G.V. Hurley. (Editors). 2005. Acoustic Monitoring and Marine Mammal Surveys in The Gully and Outer Scotian Shelf before and during Active Seismic Programs. Environmental Studies Research Funds Report No. 151, xx + 154 p.

- LGL Ltd. Environmental Research Associates. 2000. Assessment of Noise Issues Relevant to Key Cetacean Species (Northern Bottlenose and Sperm Whales) in the Sable Gully Area of Interest. Prepared for: Oceans and Coastal Management Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

- Macnab, P.A., Murphy, S., and Normandeau, A. 2017. Assessing and mitigating the risk of multibeam echosounder use near endangered beaked whales in the Gully Marine Protected Area. Canadian Acoustics 45(2):11-2.

- Marotte, E. and Moors-Murphy, H. 2015. Seasonal occurrence of blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) vocalizations in the Gully Marine Protected Area. Canadian Acoustics 43(3).

- Moors, H.B. 2012. Acoustic monitoring of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus) in the Gully and adjacent areas. PhD thesis, Biology Department, Dalhousie University.

- O'Brien, K., and Whitehead, H. 2013. Population analysis of endangered northern bottlenose whales on the Scotian Shelf seven years after the establishment of a Marine Protected Area. Endangered Species Research 21:273-284.

- Stanistreet, J.E., Feyrer, L.J., and Moors-Murphy, H.B. 2021. Distribution, movements, and habitat use of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus) on the Scotian Shelf. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2021/074. vi + 34 p.

- Whitehead, H. 2013. Trends in cetacean abundance in the Gully submarine canyon,1988–2011, highlight a 21% per year increase in Sowerby's beaked whales (Mesoplodon bidens). Canadian Journal of Zoology. 91:141–148.

Ecosystem science

- Desharnais, F. and N.E.B. Collison. 2001. Background noise levels in the area of the Gully, Laurentian Channel and Sable Bank. Defence Research Establishment Atlantic. ECR 2001-028. x + 36 p.

- DFO. 2022. 2021 Review of Baseline Information, Monitoring Indicators, and Trends in the Gully Marine Protected Area. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2022/017.

- DFO. 2010. Gully Marine Protected Area Monitoring Indicators, Protocols and Strategies. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2010/066.

- Fenton, D. G., P. A. Macnab, and R. J. Rutherford. 2002. The Sable Gully Marine Protected Area Initiative: History and Current Efforts. In S. Bondrup-Nielsen, N.W.P. Munro, G.J.H. Nelson, M. Willison, T.B. Herman and P. Eagles (Editors). Managing Protected Areas in a Changing World. SAMPAA, Wolfville, Canada (2002). p. 1343-1355

- Gordon, D.C. and D.G Fenton (Editors). 2002. Advances in Understanding The Gully Ecosystem: A Summary of Research Projects Conducted at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography (1999-2001) Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2377: vi + 84p.

- Harrison, W.G. and D.G. Fenton (Editors). 1998. The Gully: A Scientific Review of its Environment and Ecosystem. Canadian Stock Assessment Secretariat Research Document 98/83: x + 282 p.

- Jeffery, N.W., Stanley, R.R.E., and Heaslip, S.G. 2021. Monitoring connectivity and climate change in the Gully Marine Protected Area. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 3453: vii + 52 p.

- Kenchington, T.J. 2010. Environmental Monitoring of the Gully Marine Protected Area: A Recommendation. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2010/075: vi + 59 p.

- Mortensen, P.B. and L. Buhl-Mortensen. 2005. Deep-water corals and their habitats in The Gully, a submarine canyon off Atlantic Canada. In A. Freiwald, J.M. Roberts (Editors) Cold-Water Corals and Ecosystems. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, p. 247–277.

- Rutherford, R.J. and H. Breeze. 2002. The Gully Ecosystem. Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2615: vi + 28 p.

- Yeung, C.W., K. Lee, L.G. Whyte and C.W. Greer. 2010. Microbial community characterization of the Gully: a marine protected area. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 56: 421-431.

Management

- DFO. 2017. The Gully Marine Protected Area Management Plan. Second Edition. Oceans and Coastal Management Division. 2017. 68p.

- DFO. 2008. The Gully Marine Protected Area Management Plan. Oceans and Habitat Branch, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2008. 76 p.

- DFO. 2004. Gully Marine Protected Area Regulations. SOR/2004-112.

- VanderZwaag, D.L. and P. Macnab. 2011. Marine protected areas: Legal framework for the Gully off the coast of Nova Scotia (Canada). In B. Lausche (Editor) Guidelines for Protected Areas Legislation. 2011. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. xxvi + 370 p.

- Westhead, M.C., D.G. Fenton, T.A. Koropatnick, P.A. Macnab and H.B. Moors. 2012. Filling the gaps one at a time: The Gully Marine Protected Area in Eastern Canada. A Response to Agardy, Notarbartolo di Sciara and Christie. Marine Policy 36: 713-715.

- Date modified: