What we heard report: Advancing an ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM)

On this page

Executive summary

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is committed to employing an ecosystem approach to fisheries management (EAFM), which is intended to enhance the understanding of fish stock abundance and dynamics through the consideration of environmental information to support fisheries management decisions. To date, this approach has been implemented opportunistically and incrementally in some fisheries, but not yet comprehensively or systematically across all the stocks and fisheries that DFO manages.

DFO's working definition for EAFM is a single-stock approach to fisheries management that incorporates ecosystem variables into stock assessments, science advice, management recommendations, integrated fishery management plans or other harvest strategies (i.e., the science-management cycle) to better inform stock and individual fishery-focused decisions. EAFM enhances single-stock management, and represents a step towards explicitly considering various trade-offs inherent in the management of fisheries resources, e.g., stock and ecosystem conservation, social, economic and cultural factors, among others, over varying time and spatial scales. It is anticipated that incremental advances in EAFM could lead to more holistic ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) in the longer term, which adopts a multi-stock assessment and management perspective within a particular ecosystem and further balances social and ecological needs. In this context, EAFM will become increasingly important as a management approach that helps to incorporate environmental information into science advice and fisheries decision-making, to enable sustainable and prosperous fisheries.

In the fall of 2023, DFO developed its “Advancing an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management: A Discussion Document” (referred to as “the Discussion Document”) to advance on a strategic plan and a more systematic implementation of an ecosystem approach for managing fisheries. DFO held virtual engagement sessions across all regions in September and October, dedicated to the discussion of EAFM, and sought input, feedback and views of Indigenous peoples, co-management partners, fish harvesters, industry, governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and others. Additionally, DFO participated in various other stakeholder meetings and engagements throughout October and early November to discuss EAFM and the Discussion Document, at the request of Indigenous peoples and stakeholders. In total, more than 500 Indigenous peoples and stakeholders were invited to participate in the engagement sessions.

In addition to the extensive comments provided by participants during the virtual engagements, DFO received a total of 24 formal written responses from Indigenous peoples and stakeholders who attended the sessions. Overall, the department received a broad range of comments and views on how to proceed with EAFM and its implementation, and a general expression of interest in advancing these efforts while recognizing the challenges of undertaking such an initiative. The majority of feedback focused on the scope of EAFM application (e.g. single-stock versus multi-stock assessments and management approaches) and scale (e.g. types of stocks, such as marine, freshwater, commercial, non-commercial), as well as the challenges that EAFM may create with respect to current policies and departmental objectives. Other feedback related to funding, resources, and capacity of the department to implement EAFM while continuing to work towards achieving other science and management obligations, and opportunities for greater inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge in informing EAFM-related advice and recommendations.

As previously noted, Indigenous peoples and stakeholder views obtained during outreach and engagement on the Discussion Document were intended to help inform the future departmental strategic plan for EAFM.

Overview

DFO sought written feedback and views on the Discussion Document with the intent to help advance a strategic plan for the department and lead to a more systematic implementation of EAFM. The Discussion Document provided a high-level perspective on EAFM and the department's current thinking about its wider adoption. The department's objectives for EAFM are to support the overarching goals of (i) securing economic prosperity in the fishing sector while (ii) fostering productive and sustainable marine ecosystems to support that prosperity over the long term, a future expected to be disrupted by climate change and other ecosystem variability.

The intent of the virtual engagements was to solicit feedback from Indigenous peoples and stakeholders about the broad adoption of an EAFM for federally managed fish stocks and fisheries in Canada. To help initiate and facilitate discussion and generate feedback, the Discussion Document included several questions (not intended to be exhaustive or represent the full range of points that could be raised) to better understand:

- Changes they have noticed or experienced regarding fish stocks;

- The level of concern about the future of their respective fishery/fisheries;

- Stocks affected by ecosystem factors that should be prioritized;

- What are potential positives and/or negatives of EAFM;

- Their role in the development/implementation of EAFM;

- Other forums that could be helpful to advance EAFM; and

- How they would like to be engaged on EAFM in the future

The department received a total of 24 written responses from Indigenous peoples, co-management partners, fish harvesters, industry, governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and others across Canada, representing interests across all regions. Indigenous peoples and Indigenous organizations, fishing associations and industry, as well as NGOs each accounted for 29% of the written responses received, while provinces/territories accounted for the remaining 13%.

Process

From September through November 2023, DFO held dedicated virtual engagement sessions on advancing EAFM in the Pacific, Arctic, Quebec, Gulf, and Newfoundland and Labrador Regions. DFO utilized the Scotia-Fundy Roundtable as an engagement opportunity in the Maritimes Region, given the diverse and extensive representation in that forum. In addition, the department engaged virtually on EAFM at various advisory and joint committee meetings and other relevant meetings, at the request of Indigenous peoples and stakeholders across the country. Indigenous peoples, Indigenous organizations, fish harvesters, industry, governments, NGOs, and others participated in the virtual engagement meetings. The Discussion Document was circulated in advance of the sessions and meetings, and engagements allowed time for participants to ask questions and provide oral comments. Participants were encouraged to provide further comments in written form, via email.

Emergent themes

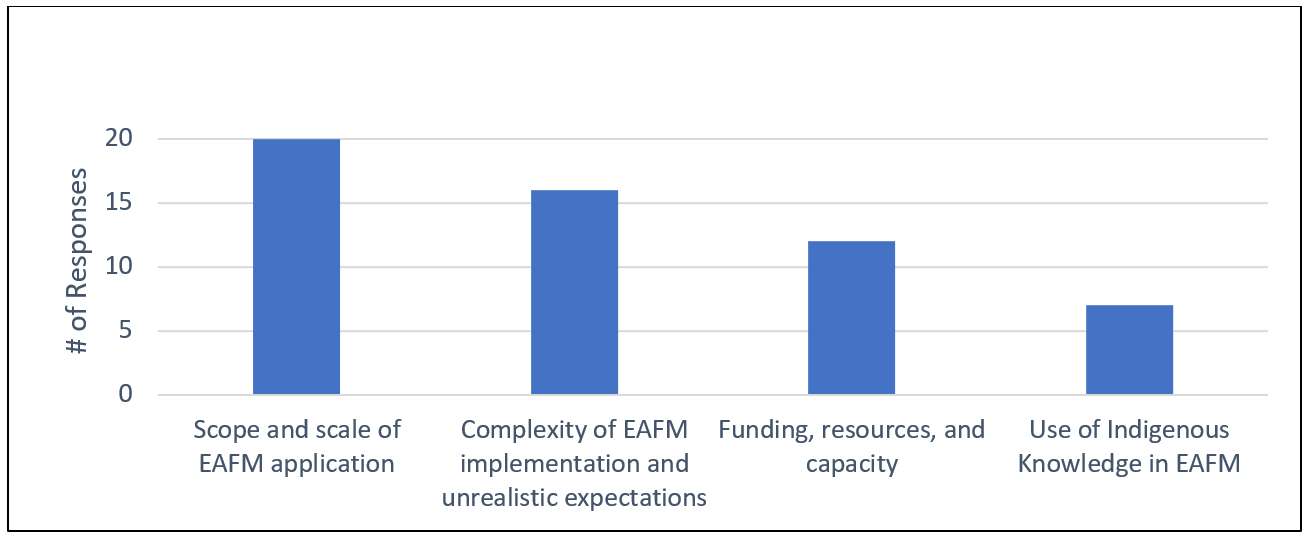

Most comments heard during the virtual engagements and throughout the written responses fell under four overarching, key emergent themes (Figure 1):

- scope and scale of EAFM application

- complexity of EAFM implementation and unrealistic expectations

- funding, resources, and capacity

- the use of Indigenous Knowledge.

Other comments focused on the need to consider economic impacts, and the need for departmental transparency and consistency with fisheries management decisions. While the department provided some targeted questions to initiate and facilitate discussion, as noted earlier, few respondents answered these questions directly.

Figure 1: Number of written responses received for key emergent themes

Long description

Bar chart showing the number of written responses for each of the four key themes. The Y axis of the chart represents the number of responses, increasing in increments of five, and the X axis lists the four key themes.

Going from left to right, the chart shows that key theme with the highest number of responses (20) is "scope and scale of EAFM application". The next theme is "complexity of EAFM implementation and unrealistic expectations", with 16 responses. The "funding, resources, and capacity" theme is next, with 13 responses. Finally, the "use of Indigenous Knowledge in EAFM" theme is the furthest along the X axis, with 7 responses.

Theme 1: Scope and scale of EAFM application

Eighty-three percent (83%) of the written responses related to the scope and/or scale of EAFM application. The scope of EAFM refers to the management approach of the fish stocks (i.e. single stock vs. multi-stock). Indigenous peoples and NGOs were most likely to suggest that DFO aim for EBFM or Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM), which manage fisheries at the multi-stock level and account for more factors that can impact stocks. Rationale included a general perception that EAFM will not go far enough to account for other important factors, like human impacts. The department heard that it should aim to be consistent with the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization and the Convention on Biological Diversity roadmaps on EBFM and EBM, and should consider human impacts in fisheries management (e.g. aquaculture, logging, agriculture, mining, tires, ocean dumping). The fishing industry tended to acknowledge EAFM was an appropriate step forward for advancing consideration of environmental variables, but cautioned against EBFM and EBM application at this time, citing the complexities associated with these levels of management and the scarcity of their implementation internationally. Multiple fishing associations said they would want additional consultations if the department were to move forward with EBFM or EBM as this would be a significant shift from the way fish stocks are currently managed in Canada.

The scale of EAFM refers to the types of fisheries or fish stocks to which EAFM would be applied (e.g. marine, freshwater, commercial, non-commercial) and the method through which it would be applied (e.g. broad or national application vs. case by case or fishery-specific application). Several Indigenous respondents and NGOs felt the Discussion Document focused primarily on marine commercial fisheries, and argued that other fisheries should be considered as well, such as anadromous species which rely on freshwater habitats for juvenile development (e.g. Pacific salmon and Atlantic salmon), non-commercial stocks, and fisheries of Food, Social and Ceremonial (FSC) importance to Indigenous peoples. Other respondents suggested the department should focus on lower trophic levels and should consider the role of forage fish in the ecosystem, while some suggested implementation should be broad enough to apply to any federally-managed fish stock in Canada. As well, some respondents suggested the department should carry out a public survey to assess which fish stocks should be prioritized for EAFM implementation in the future.

While some respondents suggested EAFM application should be applied broadly and consistently across Canada, others expressed the need for DFO to consider regional differences, particularly in the North, as data availability and fisheries-related priorities can vary. Other comments included using a phased approach to EAFM implementation, with one respondent suggesting the Newfoundland and Labrador Region should be used as a pilot for EAFM given the recent development of comprehensive ecosystem assessments, including oceanographic and multi-species considerations, and progress made in advancing an ecosystem approach to the development of reference points for Northern cod.

Theme 2: Complexity of EAFM implementation and unrealistic expectations

Two thirds of the respondents (67%) identified challenges related to the perceived complexity of implementing EAFM and felt the expectations of EAFM may be unrealistic. This included views that including environmental variables in stock assessments would further increase the complexity of science advice (e.g., with respect to Limit Reference Points and the Precautionary Approach) and could thereby cause additional challenges to the current management of fisheries. Others shared concerns that poor data or coarse proxies for environmental variables could be used by the department as the best available information and could lead to increased uncertainty in science advice and inconsistent or unreliable fishery management decisions, which would be further exacerbated by the lack of long-term funding for EAFM. Additional feedback related to the potential complexity of EAFM included a perceived risk that the use of environmental variables in stock assessments would restrict or otherwise negatively impact decisions (e.g., decreases in Total Allowable Catch). Some respondents suggested that environmental variables be incorporated into advice and decisions only when they are shown to be robust and demonstrate a benefit to management decisions. One such comment was that some environmental variables, such as predator-prey interactions, could negatively impact how one species could be perceived if it is found to have negative impacts on another species, even if they are both considered targeted species (e.g., commercial stocks).

Other views expressed some confusion regarding how EAFM would fit into existing DFO regulations, policies and management tools, particularly the Sustainable Fisheries Framework and Integrated Fisheries Management Plans, and whether new policies would have to be created. Some questioned how the implementation of EAFM would be different than previous efforts to include ecosystem approaches, such as with the 2009 Precautionary Approach Policy or in the new Fish Stocks Provisions of the modernized Fisheries Act for Canada. Additionally, feedback suggested that the department needs to fully apply the suite of tools associated with the Precautionary Approach Policy in order to achieve successful EAFM implementation. There are expectations that a DFO EAFM strategic plan will provide greater clarity for resource users by explaining, for example, how EAFM will address existing policy gaps or which policies will be updated. Overall, respondents expressed the need for fishery managers and stakeholders alike to have a clear policy to follow when implementing EAFM. A few respondents also noted a need for the department to fully implement the Fishery Monitoring Policy more quickly, and that new monitoring programs need to be implemented first in order for EAFM to be achieved in Canadian fisheries.

Given the perceived complexity of implementation, some comments cautioned that the rate at which the department is engaging on and aiming to establish EAFM is too quick, and more time and additional engagements are required for uptake and success at the fishery level. However, others suggested that departmental implementation should be accelerated given the general positive state of understanding and acceptance of ecosystem approaches to management, both domestically and internationally, and the current level of urgency that drives the need for adaptation by the department in the face of biodiversity loss and climate change-induced effects on aquatic ecosystems.

Lastly, some views and comments suggested that DFO has too many siloes across its programs, and there is a need for a framework to better increase collaboration across the department and with other federal departments, and for work to reduce or remove existing barriers to collaboration.

Theme 3: Funding, resources, and capacity

Half of the respondents (50%) shared views and concerns regarding potential challenges associated with limited funding, adequate resources, and sufficient capacity for DFO to effectively implement EAFM. Many respondents felt the department currently struggles to complete core fisheries science to support existing management practices, and that current DFO resources and capacity are not adequate to support additional work related to advancing EAFM implementation. These respondents noted a general concern that without significant additional funding dedicated to EAFM, there is a risk that existing resources may potentially be diverted from core fisheries science. The department also heard that new funds would be necessary to collect more data, and more reliable data, on new and existing environmental variables, and that analytical expertise would be required for modelling. Indigenous groups, NGOs, and fishing industry expressed an interest in contributing to EAFM implementation through, for example, data collection and sharing their knowledge of ecosystems.

Theme 4: Use of Indigenous Knowledge in EAFM

Over one quarter (29%) of respondents, including Indigenous peoples, Indigenous organizations, NGOs, and provinces and territories, said EAFM should include Indigenous Knowledge. Some felt the Discussion Document was focused on Western science and that fisheries co-management, or Indigenous-led fisheries management, would allow for increased use of traditional knowledge and contribute to an improved implementation approach. In general, respondents expressed the desire for Indigenous peoples to be included in EAFM from the early stages of policy development through implementation, including the development and update of fishery management plans. Respondents noted that Indigenous peoples have been using a broad ecosystem-based approach for centuries based on traditional ecological knowledge, and a departmental EAFM strategic plan should include language that will allow for the use of Indigenous Knowledge in contributing to science advice and fishery management.

Feedback also noted the Government of Canada's obligations under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and that this should be reflected in EAFM development and implementation.

Other comments: Socio-economic considerations and consistency in fishery management decisions

Other feedback noted the importance of socio-economic considerations in EAFM. While some comments suggested economic prosperity should not be a priority of EAFM, others indicated a need for DFO to ensure there is a strong socio-economic component to EAFM, including the potential for EAFM to consider the positive benefit that ecosystems provide to Canadians (e.g., food production, carbon storage, nutrient cycling, tourism, culture).

The department also heard the request for transparency and consistency in fishery management decisions made in accordance with EAFM. Respondents expressed that it would be important for EAFM to articulate how the impacts of environmental variables will be considered for various decisions and in different circumstances, and whether the inclusion of environmental variables in stock assessments could result in different management outcomes. One suggestion was that the department create an interim approach via an “ecosystem unit” which could examine stock assessments, fishery management decisions, and enhancement and restoration plans to ensure there is consistency and that these are reflective of a standardized ecosystem approach.

Conclusion and next steps

Overall, the department received a broad range of comments and views on how to proceed with EAFM and its implementation, and a general expression an interest in advancing these efforts while recognizing the challenges of undertaking such an initiative. The department is grateful for the extensive and comprehensive feedback received through the engagements and will take these views and comments into consideration when drafting an EAFM strategic plan, which will provide the department the necessary foundational guidance to inform the implementation of EAFM at the fishery level.

- Date modified: