First-generation Marine Spatial Plan: Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy

Note

The development of this plan has been led by DFO Maritimes Region based on collaboration, input and the priorities identified by key participants to date. The plan reflects the interests gathered through initial engagement within DFO and with other federal departments, the Provincial Governments of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and Indigenous communities. DFO Maritimes Region recognizes that the priorities and interests of these groups may change over time as we continue to engage. Reaching a degree of shared understanding and interest from these organizations, given their legislative authorities and rights, was considered a necessity to assess their interest to proceed with MSP. While engagement of these groups has been a priority, DFO acknowledges some of the challenges of their participation, including varying capacity and time availability, as well as the workplace disruptions caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic, and will continue to work with them to include their input. Across the groups that were engaged to develop the first-generation plan, there was general interest in continuing to advance MSP. The MSP process will continue to evolve as engagement continues.

Work has also begun to better understand and reflect the priorities of other important users of the marine environment including the fishing sector, municipal governments and coastal communities, offshore energy developers, ENGOs and others. This work is ongoing and will continue to be reflected in the shared priorities and work plans of the MSP Program over time.

On this page

Summary

Marine Spatial Planning is in its early stages in Canada as a tool for oceans management. It will build on past oceans management initiatives. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) helps to advance this planning under Canada's Oceans Act. Marine spatial planning considers a variety of social, cultural, economic and ecological interests.

Some of the benefits of MSP include:

- supporting economic opportunities

- reducing conflicts

- improving understanding of ocean issues

- valuing and including different points of view and knowledge systems

- planning at local to regional scales

This plan outlines how DFO advances marine spatial planning in the Maritimes Region. Our planning area includes the:

- Bay of Fundy

- Atlantic coast

- offshore Scotian Shelf

This plan is a starting point. It will guide existing planning and management efforts. It is strategic in nature and not a regulatory tool.

Engagement on the plan is ongoing and has included:

- First Nations and Indigenous organizations

- other government departments

- stakeholders

The plan reflects:

- international guidance on marine spatial planning

- knowledge of oceans management in the region

- input from regional engagement

The plan also includes information on:

- planning goals, interests and priorities

- DFO Maritimes Region

- governance arrangements

- connections to other initiatives

- feedback from initial engagement

- decision-support tools (including the Canada Marine Planning Atlas)

DFO will create a workplan to report on outcomes. We will also revisit this plan every 3 years and revise as needed.

Introduction

Purpose

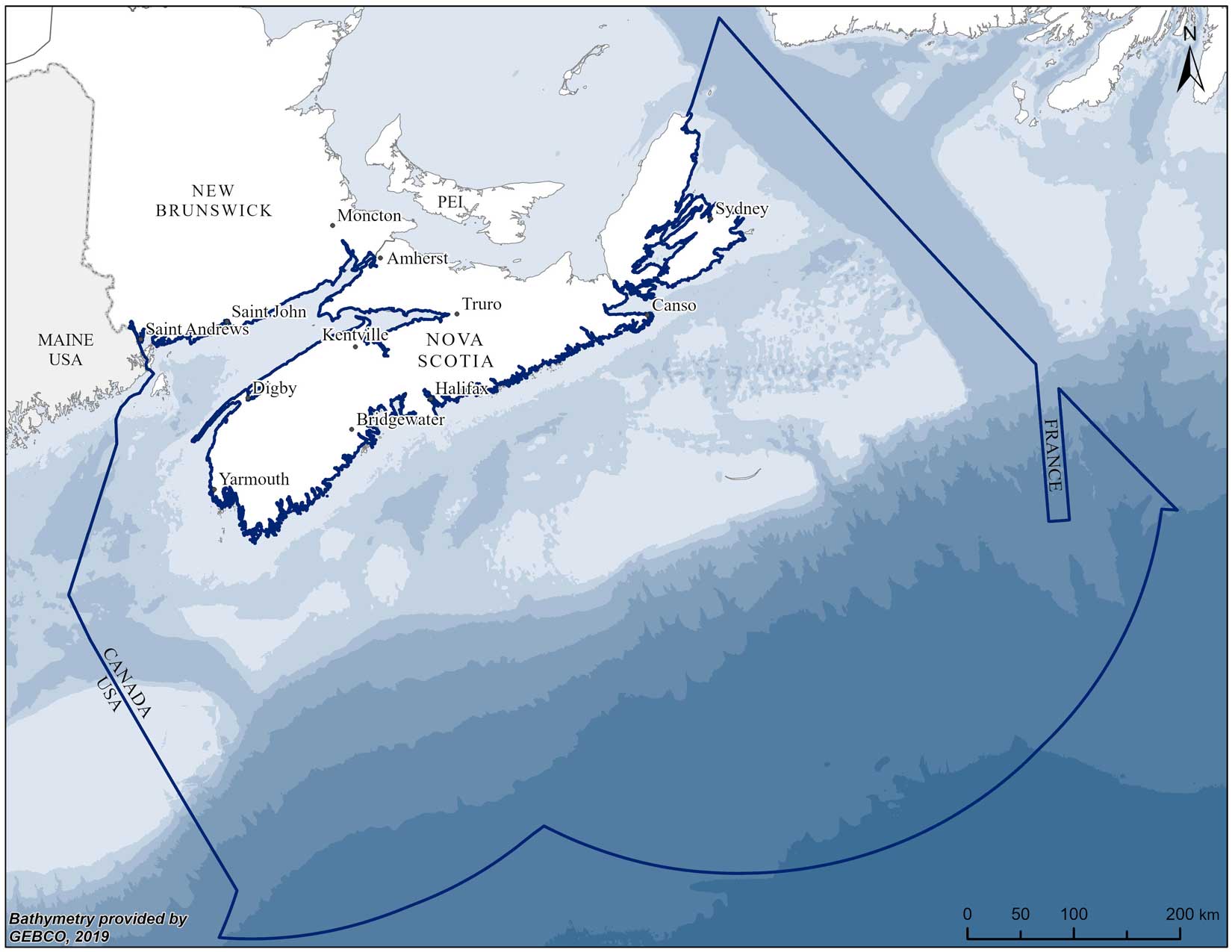

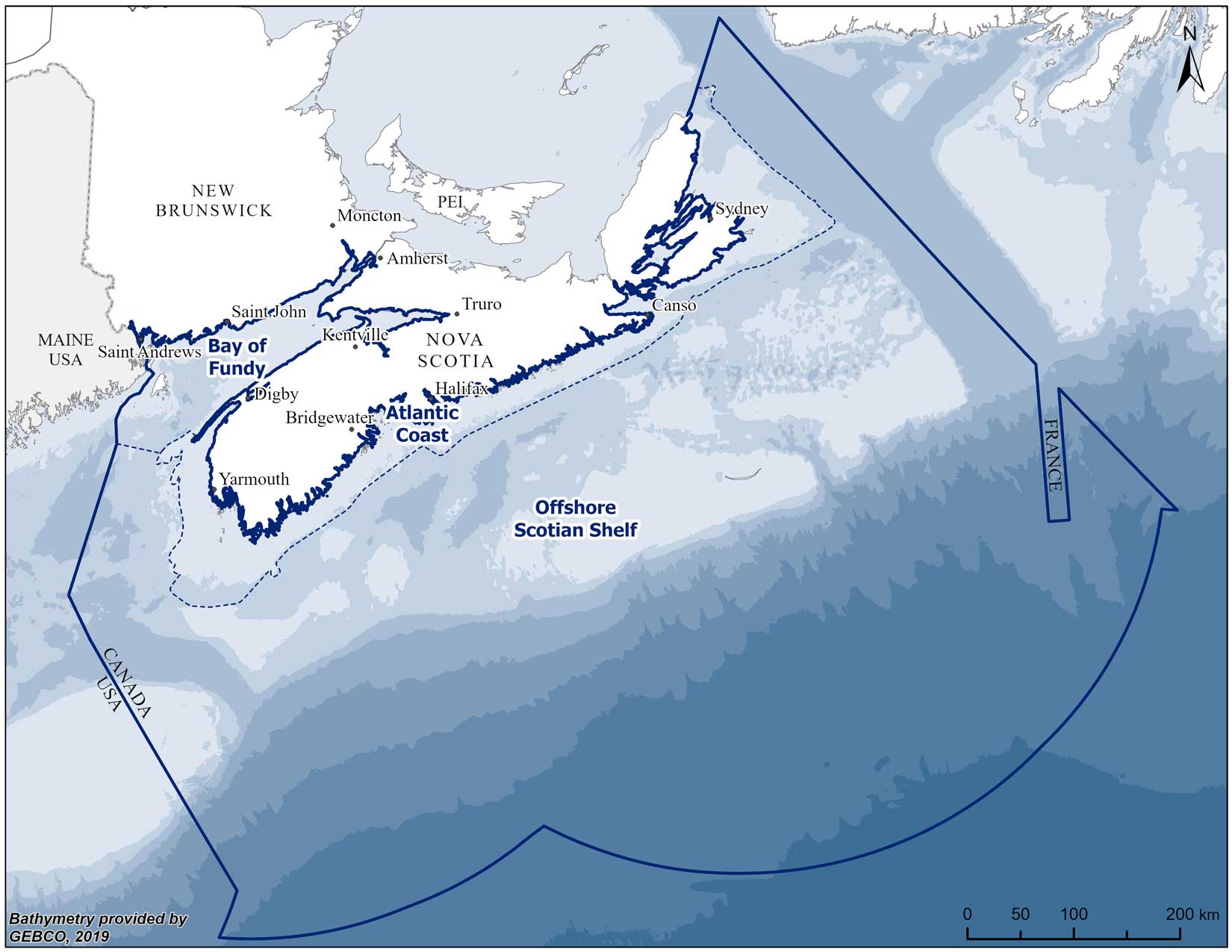

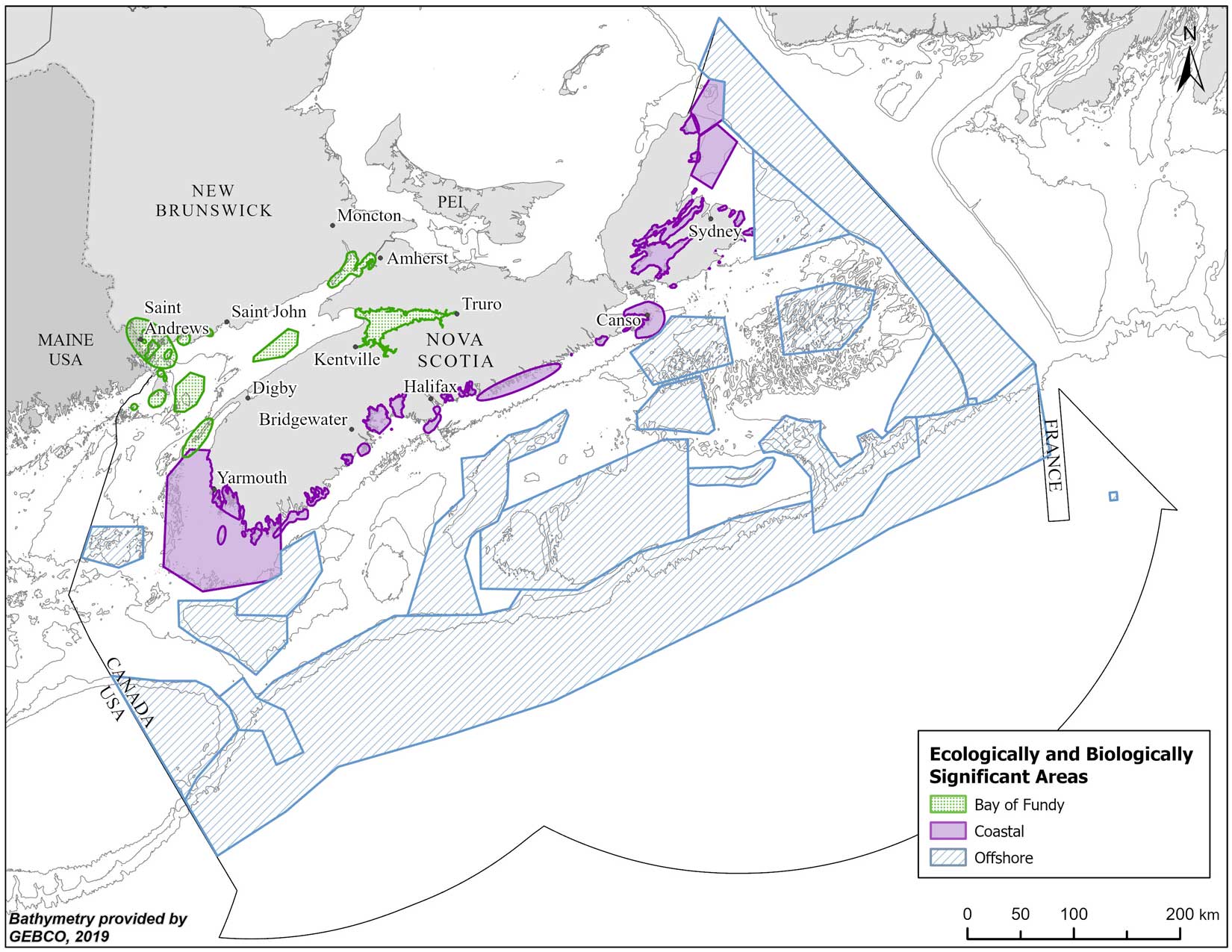

The purpose of this document is to describe the approach that is being taken to help advance marine spatial planning (MSP) in the Maritimes Region of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), which is also known as the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area. This area is shown in Figure 1 and includes:

- the Bay of Fundy

- the Atlantic Coast

- the offshore Scotian Shelf

DFO has been given the authority under Canada's Oceans Act to advance marine planning in Canada on behalf of the federal government.

As prepared by DFO, this document reflects international guidance for advancing MSP programs and the initial interests and involvement of a range of Indigenous organizations, government departments, and stakeholders. The approach taken for advancing MSP in this document reflects the lessons learned and the evolution of the ocean and coastal management work within the Maritimes Region over the past 20 years. It is acknowledged that the planning area for this work corresponds to the ancestral and unceded territories of the Mi'kmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati peoples.

In Canada, marine spatial planning is still in its early stages as a tool to implement integrated oceans and coastal management. While this is largely a DFO document now, it is hoped that others will see their interests reflected in it and the benefits of the approach being taken. It is further hoped that shared ownership will develop over time. Ongoing participation and input from the diverse range of marine stakeholders and rights holders will strengthen this work going forward and ensure that a range of social, cultural, economic, and ecological interests can be supported.

This plan is meant to guide, and not replace, the current sector-by-sector planning and management that takes place within the marine environment by a wide variety of government departments. There are no regulatory powers associated with this plan. Instead, the plan is more strategic in nature and aims to add value to existing planning and decision-making processes through:

- the provision of timely and accessible information

- spatial analysis

- decision-support tools

- governance arrangements

- collaboration

- communications

- capacity support

A concerted effort has been made to focus on the practical benefits of MSP which can include:

- supporting economic opportunities

- reducing conflicts with siting new activities

- improving awareness and understanding of ocean issues

- valuing and including different perspectives and knowledge systems

- planning at local to regional scales

This document includes background information on the key goals, objectives, and priorities this work will advance. Information on the ecological, social and economic context of the Maritimes Region, governance arrangements, linkages with other key marine initiatives and early feedback is included. Initial tools for improving planning and decision-making are described, including Canada's new online Marine Planning Atlas. Tangible outcomes will be outlined and reported in future efforts to help address the priorities identified.

This document is considered a first-generation marine spatial plan for the region and a starting point. As such it will evolve over time as efforts continue. This work will be revisited and revised as needed based on input from our partners.

Vision

Healthy marine and coastal ecosystems and sustainable communities are supported through effective participation, management and decision-making processes.

Definition of MSP

Marine spatial planning has been defined in different ways across the globe, often reflecting the elements which support or constrain its adoption. For this current plan, MSP is defined as a process for supporting the management of ocean spaces that considers a range of ecological, economic, cultural, and social objectives.

The MSP process strives to build on previous work and bring together government regulators, Indigenous groups, stakeholders, and communities. Marine spatial plans are tailored to each unique planning area to help manage human activities and their impacts on Canada's oceans. Internationally, MSP is recognized as an effective tool for transparent, inclusive, and sustainable ocean planning and management with many countries using this approach to manage their ocean space. Various sectors can be involved in the MSP process, including but not limited to:

- recreation and tourism

- transportation and shipping

- conservation

- socio-cultural uses

- fishing and aquaculture

- energy

Drivers

Our ocean and coastal waters are increasingly crowded places where activities such as the following share space:

- fishing

- shipping

- oil and gas development

- cultural and spiritual activities

- recreation and tourism

- submarine cables

- aquaculture

- nature conservation

- renewable energy developments

These activities have the potential to conflict with each other in space and time and to impact the marine environment. Marine spatial planning is an attempt to better understand and consider these activities together to minimize conflicts and meet common goals.

Under the Oceans Act (1996), DFO has the authority to lead the development of integrated management plans in collaboration with other government departments and agencies, provincial and territorial governments, Indigenous authorities, and other stakeholders for all activities or measures in or affecting Canada's estuarine, coastal, and marine waters. MSP is an approach to fulfill this role. MSP also advances commitments made under the Convention for Biological Diversity and the recent Global Biodiversity Framework Target 1 that calls for areas to be under inclusive spatial planning.

MSP is also a tool for DFO to meet commitments for marine conservation. The 2021 Mandate Letter calls for the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard to ensure Canada meets its goals to conserve 25 percent of its oceans by 2025 and 30 percent by 2030 (see Annex A for more information on conservation).

Shouldn't MSP include a zoning plan?

The current first-generation marine spatial plan is not a multi-use zoning plan for the Maritimes region which allocates all marine uses to specific areas and times. As described in the Legislative context section, while DFO is the lead for advancing MSP under the Oceans Act, it does not currently have the legislative authority to develop a plan that regulates all users in such a manner. Other legislation as administered by a wide range of government departments continues to apply to managing these marine uses including if, where, when and how they take place. In addition, even if the legislative authority were in place to pursue this form of MSP, considerable time, collaboration and willingness by all parties would be required to reach agreement on such an overall allocation of space within the Maritimes region. As a result, DFO has not pursued a multi-use zoning scheme as part of this first-generation plan.

The first-generation plan focuses on the development of other foundational improvements possible in marine management under MSP. These include enhanced decision-making based on accessible and timely information, mapping and other decision-support tools, effective governance arrangements and capacity enhancement for partners that will together improve how the oceans are managed at both local and regional scales. A multi-use zoning scheme could be pursued in the future if the legislative requirements are in place and if deemed desirable by those sharing the marine space in the Maritimes region.

Principles

The marine spatial plan will support applying the following principles and concepts to the work being undertaken. Several important Mi'kmaw principles and definitions are described, and other Indigenous principles will be sought through ongoing engagement.

Reconciliation: Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples is a commitment of the Government of Canada based on the recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership. Opportunities to advance reconciliation through the MSP Program will be pursued, including strengthening relationships with Indigenous organizations, and incorporating their interests. The planning area for this work corresponds to the ancestral and unceded territories of the Mi'kmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati peoples.

Sustainable development: Sustainable development is the economic development of resources that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs.

Adaptability: Adaptive management recognizes that conditions are continually changing, and management practices must be flexible to respond to these changes.

Ecosystem–based: Ensures that ecosystem sustainability and function is of primary importance in MSP processes and that human activities and environmental stewardship are considered in a multi-use context.

Area-based: Area-based (or spatial) management is an approach that applies management measures (i.e., regulatory tools) to a specific geographic area to achieve a desired policy outcome or planning objective.

Evidence-based: Ensures that processes are informed by the best available information from diverse scientific disciplines and knowledge bases, including that from partners and stakeholders as appropriate.

Participatory: A participatory approach is used to engage and involve Indigenous communities and organizations, federal, provincial, and municipal levels of government, marine and coastal sectors, and the broader public in the marine spatial planning process.

Key Mi'kmaw principles and definitions

Text prepared by the Kwilmu'kw Maw-Klusuaqn for the St. Anns Bank MPA Management Plan (DFO 2023a)

- Netukulimk

- is the use of the natural bounty provided by the Creator for the self-support and well-being of the individual and the community. Netukulimk is achieving standards of community nutrition and economic well-being without jeopardizing the integrity, diversity, or productivity of our environment.

- Etuaptmumk

- or Two-Eyed seeing is a balanced respect, appreciation, and consideration for Indigenous and Western knowledge. It is learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledge and ways of knowing and learning to use both eyes together for the benefit of all. In practicality, Two-Eyed Seeing is about co-learning, co-production of knowledge, and implies collaboration between different knowledge systems. The language spoken throughout Mi'kma'ki has the phrase Msit no'kmaq; translated, it means ‘all my relations'. It describes the Mi'kmaw relationship with the natural world, the living and non-living, in the temporal scales of past, present, and future.

- Sespite'tmnej

- To ‘look after something in a meaningful way'

- Toq'maliaptmu'k

- “We will look after it together”

- Msit no'kmaq

- “All my relations” – all things are inter-related, and we must honour and respect all life as our kin.

Reconciliation

In 2016, Canada fully endorsed and committed to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). On June 21, 2021, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act came into force, providing a roadmap for the Government of Canada and First Nations, Inuit, and Metis peoples to work together to implement UNDRIP based on reconciliation, healing, and cooperative relations. The Act affirms UNDRIP as an international human rights instrument that can help interpret and apply Canadian law. This commitment, by the Government's own admission, requires transformative change in the Government's relationship with Indigenous Peoples.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) defines reconciliation as “establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country where there is an awareness of the past, an acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behavior,” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). The Government of Canada's approach to reconciliation is guided by UNDRIP, the TRC's Calls to Action, constitutional values, and collaboration with Indigenous peoples. Reconciliation is a fundamental purpose of Section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982), which recognizes and affirms the Aboriginal and treaty rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation continues the work started by the TRC through providing stewardship of records and by promoting continued research and learning.

In the 2021 Mandate Letter, the Prime Minister directed the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard to build upon the progress that has been made with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, including supporting self-determination and advancing reconciliation. The Minister is also directed to use good scientific evidence, local perspectives, and Indigenous Knowledge while working towards ambitious conservation targets. Direction was also received to work with Indigenous partners to integrate traditional knowledge into planning and policy decisions.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP)

“Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures [technologies such as tools / artefacts], including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.”

- UNDRIP Article 31

In accordance with the Government of Canada's mandate, staff from DFO and the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) are responsible for prioritizing and advancing reconciliation through various ocean programs and initiatives. Footnote 1 How DFO employees will work towards reconciliation is outlined in a DFO-Coast Guard Reconciliation Strategy (Government of Canada 2019b). The Strategy is a whole-of-Department long-term guidance document which includes a commitment to recognizing and implementing Aboriginal and treaty rights related to fisheries, oceans, aquatic habitat, and marine waterways through action areas, guiding principles, and Departmental indicators. The long-term objectives of the Strategy are: a strengthened Indigenous-Crown relationship, recognized self-determination and reduced socio-economic gaps.

Using the DFO-CCG Reconciliation Strategy and internal guidance provided through a Regional Reconciliation Action Plan, MSP managers in the Maritimes Region will work to advance reconciliation, while recognizing that reconciliation is an ongoing process that occurs in the context of changing Indigenous-Crown relationships. Indigenous Knowledge and perspectives can be used to inform all aspects of the plan. Indigenous Knowledge will also be sought within the MSP process on a project-specific basis and will be used with the expressed permission of the groups providing it. Collaborative arrangements (e.g., Grants and Contribution Agreements) have and will continue to be created with Indigenous organizations to enhance their capacity to engage with their own community members and DFO. These agreements will allow for staffing, time, and resources to be directed towards effective participation. Lastly, collaborative agreements will strengthen the relationship between DFO and Indigenous organizations through ongoing dialogue and the identification of priorities so that the MSP Program can better support these areas.

Timelines and revisions

This first-generation Maritimes Region Marine Spatial Plan describes the current status of MSP in the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area. Feedback to shape this plan has been gathered from various organizations through a formal engagement process over the latter half of 2023, as well as from previous engagements, meetings, discussions, and the MSP Contribution Agreements in place. A summary of the feedback provided is described in the What we heard section. This approach will be revisited every 3 years and will be revised as needed.

Planning context

Figure 2. Boundary of the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area including the Bay of Fundy, Atlantic Coast and offshore Scotian Shelf.

Planning area overview

The Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area corresponds to DFO Maritimes Region's administrative boundaries and is approximately 476,000 km2. The planning area encompasses the offshore Scotian Shelf and portions of the Gulf of Maine, the Atlantic Coast of Nova Scotia, and the Bay of Fundy (Figure 2). The planning area is also called the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy bioregion in the marine conservation network planning process.

The planning area is a productive and diverse ecosystem, providing food and shelter for a variety of species ranging from microscopic plankton to the largest whales. Physical habitats are similarly diverse, with various coastal habitats, offshore banks and basins, steep slopes and underwater canyons, and the largely unknown abyssal plain.

The Atlantic Coast

The Atlantic Coast portion of the planning area includes the area from the high-water mark to the 12-nautical mile limit of the Territorial Sea extending from Cape North, Cape Breton, into the Bay of Fundy (Figure 2). The Atlantic Coast has a variety of shoreline habitats, such as:

- rocky shores and headlands

- large bays and inlets

- estuaries

- salt marshes

- sandy and rocky beaches

Information on the Atlantic Coast is patchy, with some areas studied extensively and others not at all. Several recent DFO studies have focused on identifying areas of ecological significance. Threats to coastal ecosystems are often linked to land-based sources of pollution, including effluent from wastewater treatment and runoff from coastal development, forestry and agriculture but may also include threats from climate change including sea-level rise. Another threat is the loss of habitat from residential, industrial, and commercial development. It is estimated that 70 percent of the population in Nova Scotia lives within a coastal community.

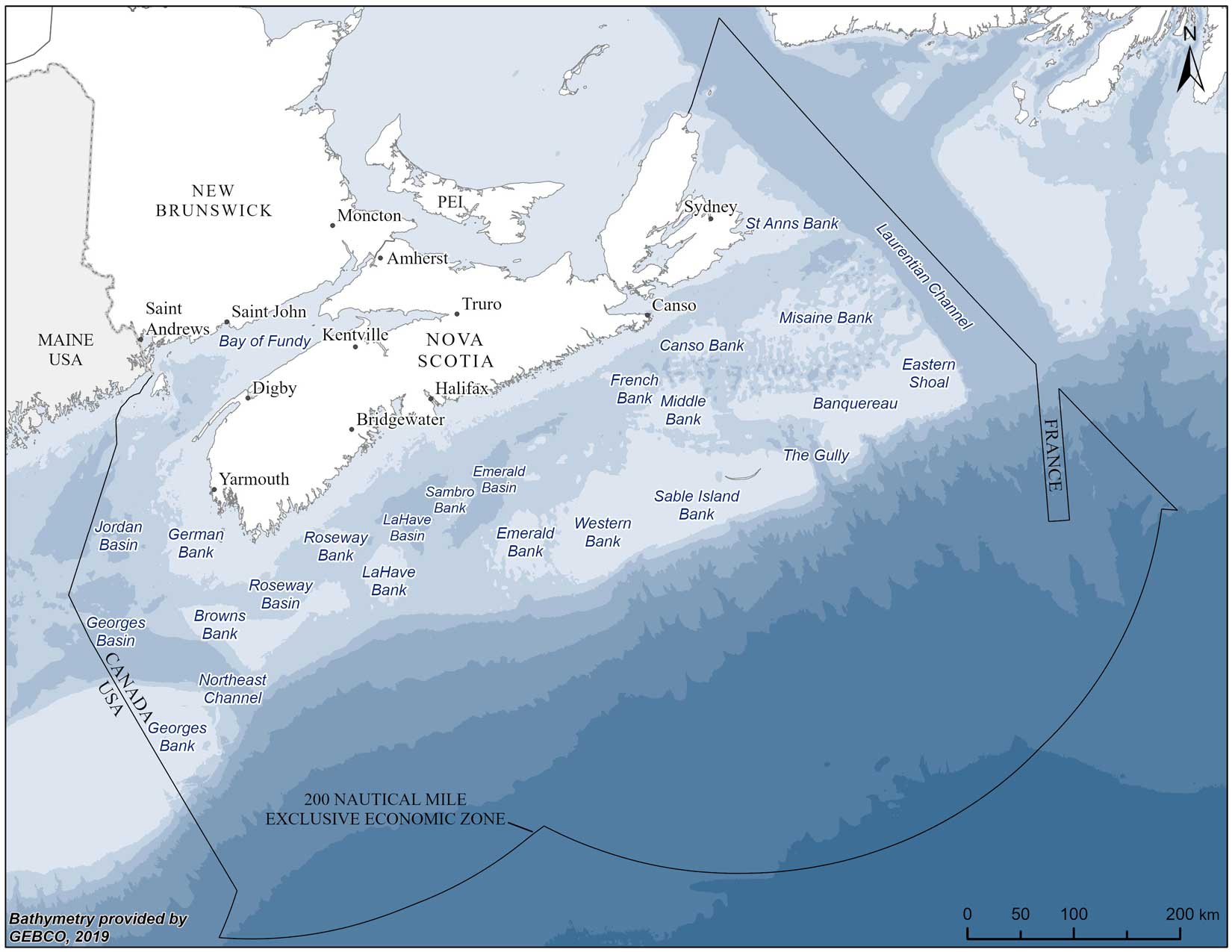

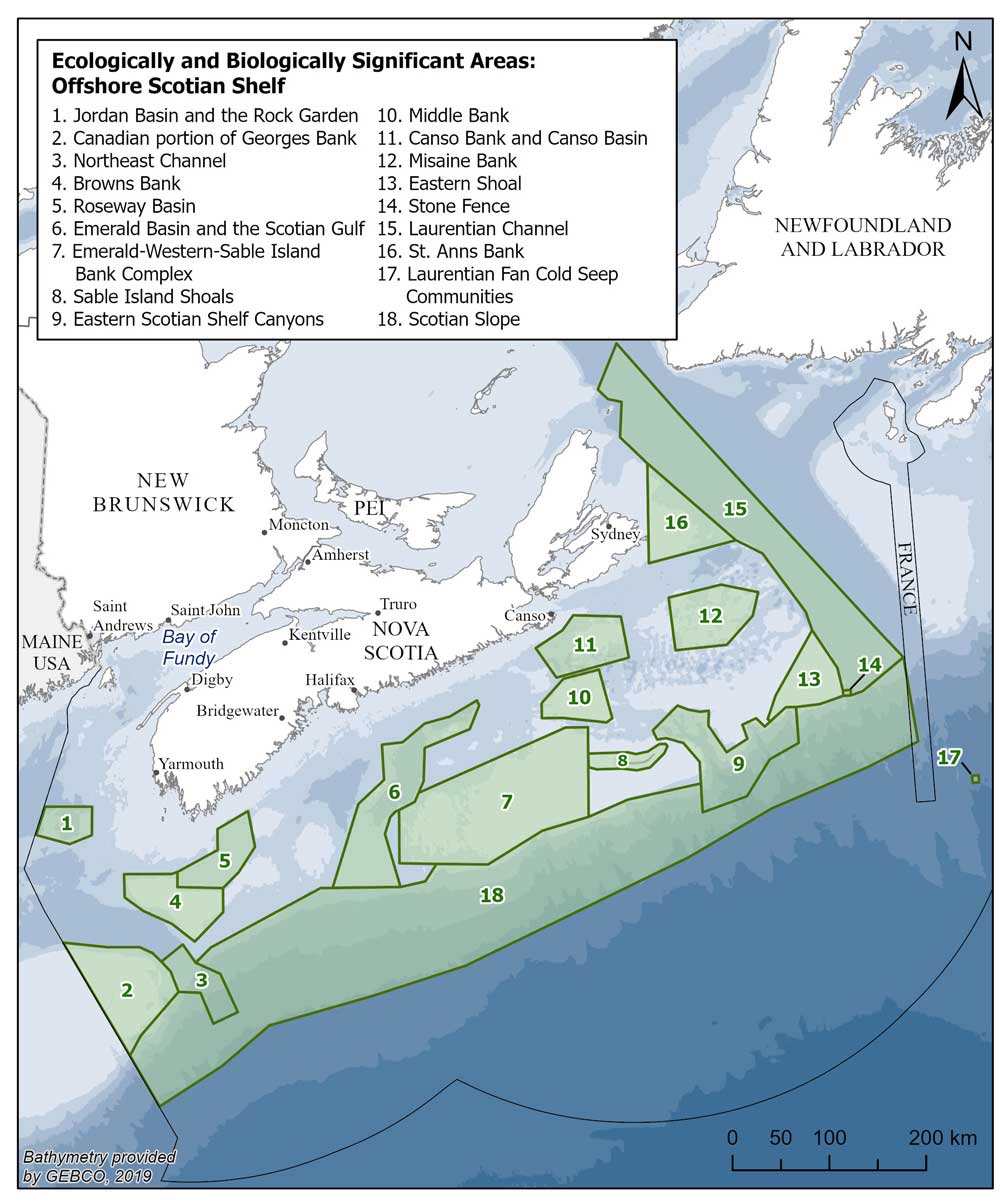

The Offshore Scotian Shelf

Moving seaward from the coast, the Offshore Scotian Shelf is defined as the waters from the 12-nautical mile limit of the Territorial Sea to the 200-mile limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone. It includes Georges Bank and offshore portions of the Gulf of Maine (see Figure 3 for location of undersea features). The Scotian Shelf is considered an underwater extension of Nova Scotia's coast. It is separated from Georges Bank in the southwest by the Northeast Channel and from the Newfoundland Shelf in the northeast by the Laurentian Channel. The edge of the Scotian Shelf and Georges Bank are indented by deep submarine canyons. The shelf edge, where the seafloor begins to fall steeply away, lies at about 200 m depth. The Scotian Shelf slope and rise (the area from the edge of the continental shelf seaward to the abyssal plain) and the portions of the abyssal plain within Canada's Exclusive Economic Zone also form part of the offshore Scotian Shelf portion of the planning area. This area is highly productive and has supported commercial fisheries for hundreds of years. Whales and seabirds feed in offshore waters, and countless invertebrates add to the area's biodiversity.

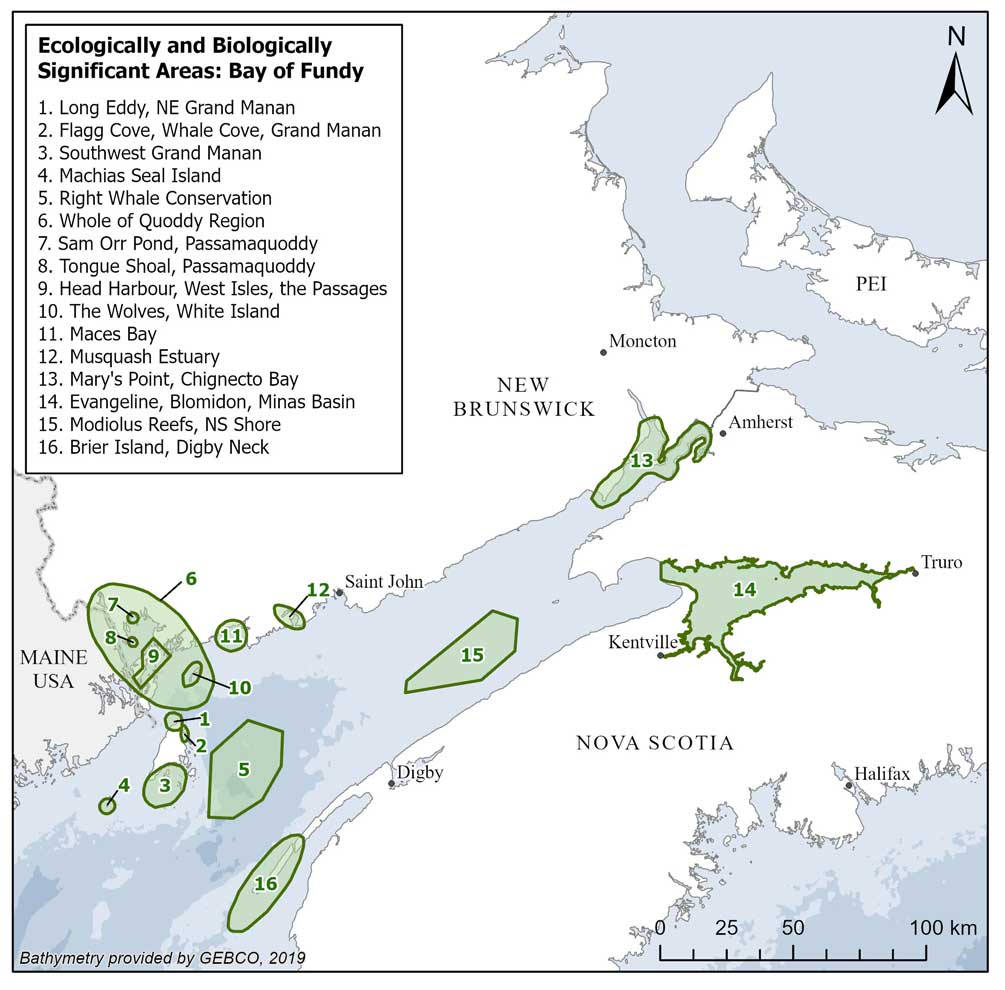

The Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy is a narrow, funnel-shaped body of water, over 270 km long and 60 km wide at its widest point. It is known for its extreme tidal ranges. The inner bay and outer bay have distinct characteristics, with the inner bay having the most extreme tidal ranges and extensive mudflats at low tide. Productivity in the area is exceptionally high and greatest at the mouth of the bay due to tidal mixing. Many different species take advantage of this productivity, including numerous marine mammals, birds, and fish. The endangered North Atlantic right whales feed on abundant copepods in the area during the summer and fall. An area in the Bay of Fundy near Grand Manan Island has been identified as critical habitat for this species (DFO 2014a). The Bay of Fundy is a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network site that provides habitat for 70 percent of the eastern biogeographic population of Semipalmated Sandpipers during migration. It was also Canada's most popular nomination for the New Seven Wonders of the Natural World competition.

Sub-regional highlight: the Minas Basin

The Minas Basin has been identified as an Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSA) by DFO (see Annex B for more information about EBSAs). The Minas Basin is a shallow macro-tidal inland sea in the Bay of Fundy, separated from the rest of the bay by a narrow strait known as the Minas Passage. It is home to a large complex ecosystem with a diversity of habitats, in part due to its high tides, which are amongst the highest in the world. The tides and resulting water movements, through constraining geological features such as the Minas Passage, result in high currents and unique physical conditions.

This area continues to be a focus for:

- in-stream tidal power development

- fish species of conservation concern, such as

- Striped Bass

- Atlantic Salmon

- Atlantic Sturgeon

- American Eel

- the Mud-Piddock, a threatened intertidal mollusk species

- species distributions of fish, shorebirds and seabirds

- studying geological oceanographic processes such as the erosion, deposition and transport of sediments that affect bottom habitat

Changes in the Atlantic Ocean ecosystem

The Atlantic Ocean is made up of different marine ecosystems interlinked by biological components and physical and chemical processes. As climate change affects the world's oceans, many of the interconnected relationships that underpin Atlantic Ocean ecosystems are being altered, causing measurable changes from coastal regions to the offshore. Species movements, habitats, and diets are shifting at different rates and scales. Certain species are moving further north or away from the coast (Pinsky et al. 2013, USGCRP 2021), aquatic invasive species are moving into newly suitable habitats (Chan et al. 2019), and some species like the North Atlantic Right Whale are changing their distribution (Meyer-Gutbrod et al. 2021). Overall declines have been observed for some species such as leatherback sea turtles (DFO 2022, Holland et al. 2023). For others, there is evidence of population increases, such as some species of sharks (Curtis et al. 2014). Certain commercially important species may decline in abundance, with others becoming more commercially important. American lobster, a highly commercially valuable species in the Northwest Atlantic, has been increasing in recent decades, although climate change could influence the long-term sustainability of this fishery (Greenan et al. 2019).

These biological shifts are occurring alongside physical and chemical changes in the marine environment such as rising sea-surface temperatures, sea ice loss, ocean acidification, and pockets of low dissolved oxygen (hypoxia) (Altieri et al 2015, Alexander et al. 2018, Doney et al. 2009, Jeffries et al. 2013). Such changes can in turn have effects on marine species such as thermal stress, habitat loss, and the creation of “dead zones” that are unable to sustain normal levels of fish and other marine species.

Future marine management actions will need to be adaptable and dynamic to be effective in addressing the effects of climate change on species, marine ecosystems, and coastal communities.

Legislative context

Sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act (1867) set out the division of powers between the federal and provincial governments. Under Section 91, the federal government has legislative authority over marine areas and fisheries within Canadian borders. Coastal and ocean management at the federal level is shared among several departments including DFO, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan),Transport Canada (TC), and Parks Canada.

Under the authority of the Oceans Act, marine spatial planning serves as a collaborative process through which integrated oceans management (IOM) may be achieved. Canada's legislative foundation for IOM lies in Part II, Section 31 of the Oceans Act which authorizes the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard to lead and facilitate the development and implementation of integrated management plans in collaboration with provincial, territorial, and Indigenous governments, other federal departments and agencies, and stakeholders.

The authority granted to the Minister to lead the development and implementation of these plans does not override other departments with roles in managing the marine environment. The endorsement and approval of a marine spatial plan by government decision-making authorities can demonstrate a commitment to implement the plan in accordance with their departmental mandates, priorities, and capacities. As marine spatial plans are not currently legally binding, there is no expectation that participating federal, provincial/ territorial, municipal departments or Indigenous governments are required to formally adopt or approve the plan.

Legislation related to Indigenous Peoples is relevant context for MSP in Canada. Section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982) recognizes and affirms existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Indigenous Peoples of Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada has indicated that the purpose of Section 35 is the reconciliation of the Crown's sovereignty and the pre-existence of Indigenous societies, Aboriginal and treaty rights, and Indigenous interests. Federal policies and programs must strive to operationalize these concepts with Indigenous Peoples through dialogue and practical approaches.

DFO's Marine Planning and Conservation Program

Implementation of the Oceans Act is led by the Marine Planning and Conservation (MPC) Program of DFO. Work is undertaken in 3 related areas:

- Marine Planning

- Marine Environmental Quality

- Marine Conservation

Marine planning

The Marine Planning section of the MPC Program is responsible for advancing marine spatial planning within the Maritimes Region. MSP is being used by DFO to meet its obligations for oceans and coastal management under the Oceans Act. This includes the development and implementation of the region's first-generation marine spatial plan and the Canada Marine Planning Atlas. It is anticipated that these efforts will continue, since much of the focus of this first-generation plan is on providing:

- timely and accessible information

- analysis

- capacity support

- engagement

- governance arrangements and communications.

Marine environmental quality

With the passing of the Oceans Act in 1996, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard was given the ability to establish guidelines, objectives and criteria, as well as standards and requirements, related to marine environmental quality (MEQ) in estuarial, coastal, and marine waters. DFO's MEQ program was revitalized in 2018 through new funding under the Oceans Protection Plan (OPP) as a component of a broader Oceans Management Program that includes marine conservation and MSP. The MEQ program aims to understand the most pressing stressors on the marine environment and develop evidence-based advice and management measures in collaboration with partners that help to fill gaps in management where additional management or mitigation of these stressors is needed. In the Maritimes Region, MEQ efforts are focused on 3 priority stressors: ocean noise, marine debris and microplastics, and marine contaminants.

MEQ project highlights

- The MEQ Coastal Acoustic Monitoring Project was launched in 2018 to better understand the presence of cetaceans and to characterize the soundscape at coastal sites across Nova Scotia. The success of the Coastal Acoustic Monitoring Project has been the result of the participation from local fishing organizations and other users of the ocean who provided invaluable knowledge and assistance to DFO during the project's planning and implementation

- The MEQ group provides funding to various marine debris cleanup initiatives, organizes and/or participates in working groups relating to marine debris and microplastics, and is developing Pathways of Effects diagrams to better understand the potential impacts of marine debris on Atlantic Canadian ecosystems and species

- MEQ also plays a supporting role in the organization and distribution of the Gulfwatch Contaminants Monitoring Program mussel sample archive and is exploring the potential for a small-scale contaminant monitoring project in Nova Scotia

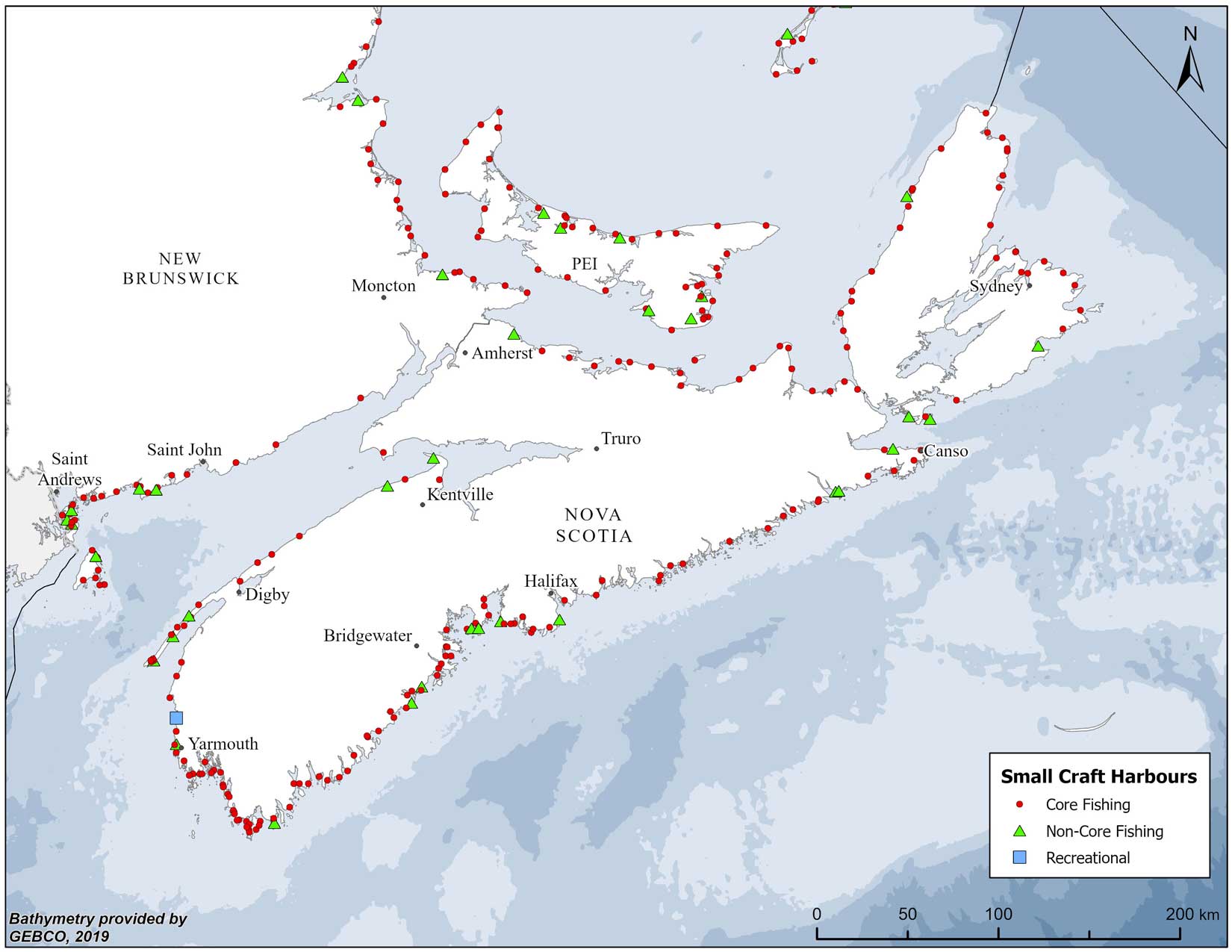

Marine Conservation

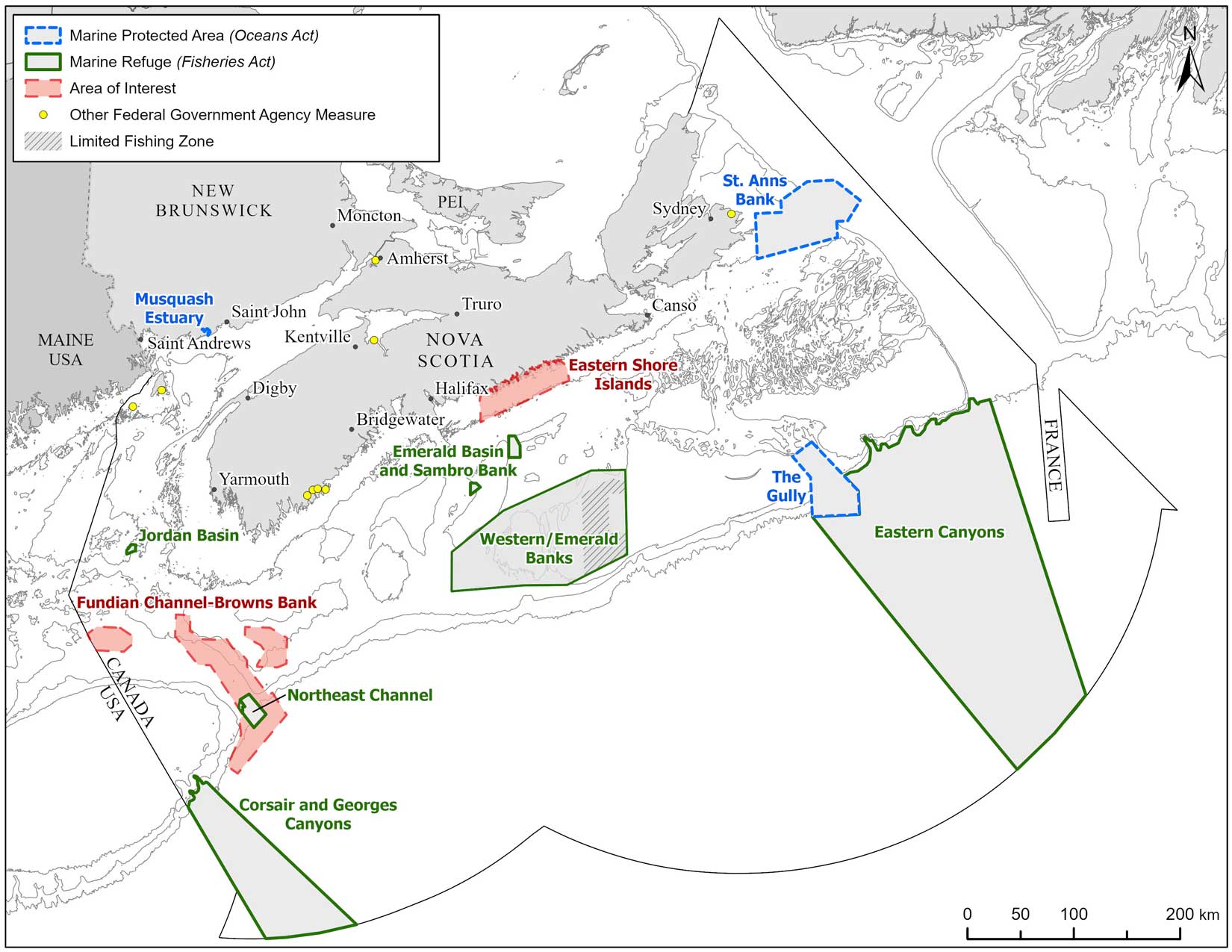

The Marine Conservation section is responsible for advancing spatial marine conservation, including work to achieve marine conservation targets of conserving 25 per cent of Canada's oceans by 2025 and 30 per cent by 2030. This work includes the establishment of Oceans Act Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and marine Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs), effective management of existing protected and conserved areas, and conservation network planning. Current Oceans Act MPAs within the Maritimes Region include the Gully, Musquash Estuary and St. Anns Bank (Figure 4). Multiple marine OECMs also exist within the bioregion including Eastern Canyons Marine Refuge, which was recently established in 2022.

Site-specific establishment and consultation processes have been initiated by DFO Maritimes for the 2 Areas of Interest (AOIs) announced in 2018 for Oceans Act MPA designation: the Eastern Shore Islands AOI and Fundian Channel-Browns Bank AOI.

Marine conservation network planning

Figure 4. Current conservation areas with marine components including Oceans Act Marine Protected Areas, Fisheries Act Marine Refuges, and other federal measures. Areas of Interest for future protection are also shown.

Under the Oceans Act, the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard is responsible for leading the development of a national network of marine protected areas on behalf of the Government of Canada.

MPA networks, which are now referred to as marine conservation networks in Canada, are a collection of MPAs and other conservation areas that operate cooperatively to safeguard important ecological components of the ocean and its biodiversity. Marine conservation networks are an important component of Canada's strategy for achieving its national and international marine conservation commitments, such as protecting 25 percent of Canada's oceans by 2025, and 30 percent by 2030.Footnote 8

Marine conservation networks are composed of both MPAs and marine OECMs. An MPA is a clearly defined geographical space that is legally protected and managed with the aim of achieving long-term conservation goals.Footnote 9 Federal protected areas are established through legislated authorities, including Marine Protected Areas under the Oceans Act (DFO), marine National Wildlife Areas under the Canada Wildlife Act (Canadian Wildlife Service), and National Marine Conservation Areas (NMCAs) under the Canada National Marine Conservation Areas Act (Parks Canada), and marine portions of National Wildlife Areas, Migratory Bird Sanctuaries, and National Parks.

Federal MPAs allow some current and future activities depending on their impacts to the ecological features being protected. In most cases, lower impact activities, such as fixed gear fisheries, recreational activities, and eco-tourism continue within conservation areas. For new federal MPAs established after April 25, 2019, the Government of Canada plans to prohibit the following activities, with limited exceptions, based on Canada's MPA Protection Standard:

- oil and gas exploration, development and production

- mineral exploration and exploitation

- disposal of waste and other matter, dumping of fill and deposit of deleterious drugs and pesticides fishing via bottom-trawl gear

Proposed additional limitations or prohibitions include the intent to enhance restrictions on certain discharges while vessels are within MPAs. The final parameters of these restrictions will be developed by Transport Canada in consultation with stakeholders and will take technical and operational limitations into consideration.

Marine OECMs, such as marine refuges (fisheries-area closures established under the Fisheries Act that meet the criteria in the Government of Canada's 2022 Marine OECM Guidance) provide long-term biodiversity conservation benefits. Footnote 1 The marine OECM Protection Standard takes a flexible, risk-based approach, where existing or foreseeable activities in federal marine OECMs continue to be assessed on a case-by-case basis to ensure that the risks to the site's biodiversity conservation objectives have been avoided or mitigated, where possible.

Marine conservation planning and site establishment have been advanced in the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy bioregion over the last 2 decades, with a number of Oceans Act MPAs and Fisheries Act marine refuges now in place and 2 Areas of Interest being advanced for establishment (Figure 4). DFO and its federal partners in Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) and Parks Canada are advancing a marine conservation network plan for the coastal and offshore waters of the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy bioregion. Undertaken through a systematic science based process, the conservation network will conserve:

- ocean ecosystems and support sustainable fisheries

- coastal communities

- other ocean activities

The conservation network will include individual sites of various shapes, sizes, and protection levels, each with its own conservation objectives. The final conservation network plan will provide long-term direction for spatial marine conservation and will be updated regularly to incorporate new information, knowledge and changing conditions to inform the selection of future marine conservation areas.

The targeted engagement phase for the marine conservation network plan was completed on March 31st, 2022. During this phase, DFO sought feedback on the 2017 plan from other federal agencies, the Provinces of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, First Nations and Indigenous organizations, and key stakeholder groups including fishing and aquaculture, as well as ENGOs and academia.

Timeline for developing the marine conservation network conservation plan for the Scotian Shelf of Bay of Fundy bioregion:

- Mid-2000s to 2017

- developing the marine conservation network plan

- July 2021 to March 2022

- targeted engagement and consultation

- April 2022 to September 2023

- revising the marine conservation network plan

- April 2024 to July 2024

- engagement and consultation

- August 2024 to November 2024

- revising the marine conservation network plan

- December 2024

- finalizing the marine conservation network plan

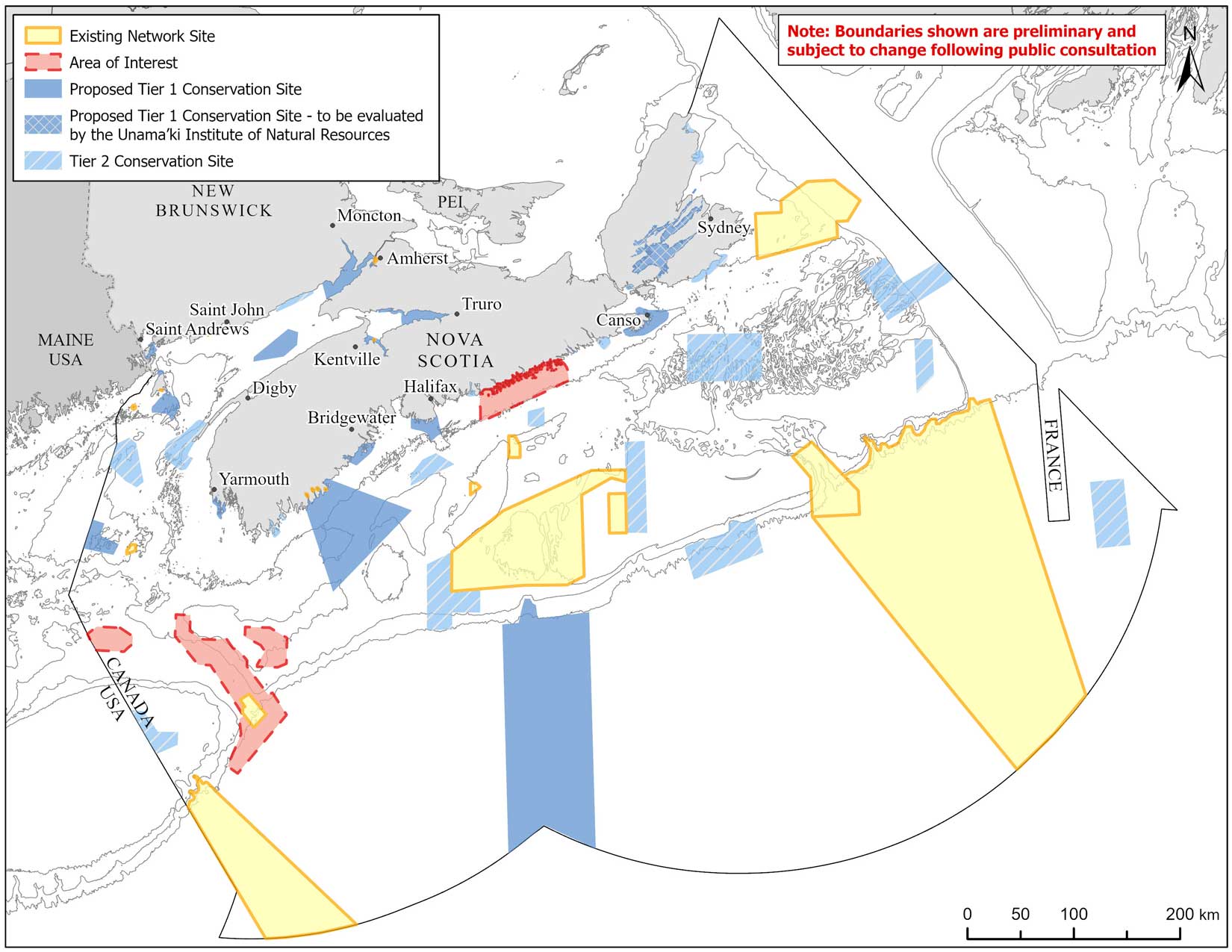

Following this phase, the department worked to review the feedback and, where necessary, scheduled follow-up meetings with those involved in the targeted engagement phase to better understand their comments and concerns. Revisions to the network plan, such as boundary revisions of a proposed site and additional DFO Science analyses, were considered. The revised marine conservation network plan was completed in Fall 2023 (Figure 5).

An engagement and awareness process, with the goal of gathering further feedback from coastal communities, partners, stakeholders, and the Canadian public, is ongoing. This feedback will be considered and incorporated as appropriate into the marine conservation network plan for the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy bioregion, which is expected to be completed by the end of 2024. Further information on the Region's network planning process can be found on the Marine conservation network development web page.

Figure 5. Revised marine conservation network for the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy bioregion as of spring 2024.

Linkage to MSP

The conservation network plan is a systematic science-based process that has included ecological, socio-economic and cultural information. MSP will support network implementation by providing updated data, enhanced governance and decision-support tools. An MSP approach will be used to deliver the federal marine conservation mandate and through this approach, partners and stakeholders are engaged to meet conservation objectives while supporting sustainable human activities. The conservation network plan is an important component of the first-generation marine spatial plan for the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area.

Indigenous communities and organizations

The waters within the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area have provided natural resources and bountiful harvests for Mi'kmaq, Peskotomuhkati and Wolastoqey peoples who have longstanding traditional and cultural connections to the marine environment and species. Providing for Indigenous peoples since time immemorial, these waters remain an economically and culturally important resource, including as an important source of food. The Mi'kmaq are the founding people of Nova Scotia and remain the predominant Indigenous group within the Province. The Mi'kmaw Nation has existed in what is now Nova Scotia for thousands of years, and is made up of thirteen First Nations, each of which is governed by a Chief and Council. All thirteen Chiefs in Nova Scotia regularly come together as the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi'kmaw Chiefs. The Assembly plays a significant role in the collective decision-making for the Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia, particularly on issues pertaining to Mi'kmaq rights and governance. In New Brunswick, the Fort Folly First Nation is the main Mi'gmag community within the planning area for DFO Maritimes and there are also 4 Wolastoqey communities and one Peskotomuhkati community at Skutik. The Indigenous communities are included in the list below.

In addition, Indigenous people reside in other communities throughout the planning area. These individuals are represented by the Maritime Aboriginal Peoples Council with individual Councils in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. This plan and its approach for engagement are meant to reflect the Department's goal of advancing reconciliation with the Indigenous communities within the planning area.

Indigenous communities within the Maritimes Region in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

Nova Scotia

- Mi'kmaq of Nova Scotia:

- Annapolis Valley First Nation

- Bear River First Nation

- Eskasoni First Nation

- Glooscap First Nation

- Membertou First Nation

- Millbrook First Nation

- Paqtnkek First Nation

- Pictou Landing First Nation

- Potlotek First Nation

- Sipekne‘katik First Nation

- Wagmatcook First Nation

- Wasoqopa'q First Nation

- We‘koqma'q L'nue'kati

New Brunswick

- Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik

- Mi'gmag of New Brunswick

- Fort Folly First Nation

- Wolastoqey Nation

- Kingsclear First Nation

- Oromocto First Nation

- Saint Mary's First Nation

- Woodstock First Nation

Aboriginal eco-centric worldview

We have lived here since the world began.

Over many generations, a sophisticated and wide body of Aboriginal knowledge, innovations, and practices have been developed throughout the traditional ancestral homelands of the Aboriginal Peoples of Canada, which enables the continuum of Aboriginal Peoples to present day. So ingrained is the knowledge, innovations, and practices of Aboriginal Peoples, which naturally includes the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the fair and equitable sharing of its benefits, that Aboriginal cultures and languages have captured these practical ideals as a matter of course and have evolved to reveal themselves within Aboriginal Peoples' “eco-centric worldview.” A tenet of the eco-centric worldview is that humankind is an integral part of the natural world, interconnected and interdependent on all other creation. The ecology of a place is paramount, with humankind as part of that, no greater and no lesser than any other part of creation.

In a recent turn of events brought about by multiple global crises, including a biodiversity and a climate crises, many now look to the potential that Aboriginal Peoples, possessing Aboriginal knowledge, practices, and innovations, can share, teach, and guide others to understand Aboriginal Peoples' concepts of conservation and sustainability, realized through the practices of “ecosystem-based management” and a “precautionary approach” which are already found in the psyche and everyday life pattern of the Aboriginal person living the traditional life-style. Though willing to teach, share, and take a step forward with those who are unfamiliar with the Aboriginal eco-centric worldview, many Aboriginal persons remain hesitant, that what is shared may be misinterpreted, misused, or may become yet another form of exploitation of Aboriginal Peoples. Aboriginal Peoples foremost require good faith and assurances that they will not be exploited and that the path will lead to reconciliation, starting with recognizing Aboriginal Peoples' rights and addressing the socio-economic development needs of Aboriginal Peoples.

The Mi'kmaq use natural resources within the context of Netukulimk, which is a Mi'kmawey concept that expresses the Aboriginal eco-centric worldview, that includes the use of the natural bounty provided by the Creator for the self-support and well-being of the individual and the community at large. The Mi'kmaq find it essential to share the principle and practice of Netukulimk with others so that they may come to understand and adopt a similar view that each component of the natural world can be preserved, protected, sustainably used, and shared in a balanced way which respects the past, provides for the present, and meets the needs for the future.

Excerpt from: Introductory Marine Planning Initiative Project. Maritime Aboriginal Peoples Council. Oceans Management Contribution Program. 2021 to 2022 Report.

Numerous First Nation-run organizations serve the diverse needs of Indigenous people in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Efforts have begun and will be ongoing to work with many of these organizations seeking their input and involvement in the marine spatial planning process. Key Indigenous organizations are included in the list below.

Key Indigenous organizations within the Maritimes Region in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

Nova Scotia

- Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi'kmaw Chiefs

- Kwilmu'kw Maw-klusuaqn Negotiation Office

- Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq

- The Union of Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq

- Unama'ki Institute of Natural Resources

- Native Council of Nova Scotia

New Brunswick

- New Brunswick Assembly of First Nations

- Wolastoqey Nation of New Brunswick

- Maliseet Nation Conservation Council

- New Brunswick Aboriginal Peoples Council

- Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik

- Migmawe'l Tplu'taqnn Incorporated

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

- Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs

- Maritime Aboriginal Peoples Council

Indigenous fisheries

Food, Social and Ceremonial (FSC): As recognized by the Constitution of Canada and clarified by the Supreme Court of Canada through the 1990 Sparrow decision, Indigenous Peoples have the right to fish for food, social and ceremonial purposes. This right can only be limited or infringed if justified in specific circumstances, such as for conservation purposes. To authorize and support the exercise of this right within an integrated fisheries management and regulatory framework, DFO issues FSC licences to Indigenous communities across Canada for a variety of species. The right to fish for FSC purposes is communal, and the FSC fishing license is issued to the Indigenous Nation. The Nation may then designate harvesters to catch what is needed for themselves and/ or their community under the licence for FSC purposes. Licences specify the species and various conditions in place to manage the fishery (geographic area, level of effort, conservation measures) under which Indigenous communities can exercise this right.

Communal Commercial: Following Supreme Court decisions affirming Aboriginal and treaty rights to fish for commercial purposes, DFO began issuing communal commercial licences, which are an integral part of many Indigenous communities. Communal commercial fishing licences, which are distinct from commercial fishing licences (issued to individuals or companies), provide fisheries access and generate employment and income for communities. Unlike catch harvested under FSC licences, the catch from communal commercial licences may be sold.

Moderate Livelihood: First Nations in the Atlantic and Gaspé region have a treaty right to fish in pursuit of a moderate livelihood. The Government of Canada recognizes this right and DFO continues to work with First Nations and communities to implement the Marshall decisions. DFO is working with these communities on the ongoing implementation of their treaty right to fish in pursuit of a moderate livelihood while maintaining a sustainable fishery for all harvesters. There are different approaches to further implement treaty rights, depending on Treaty Nations' preferences: medium-to-long-term Rights Reconciliation Agreements (RRA); and short-term understandings based on community-developed moderate livelihood fishing plans for a fishing season. DFO has been working with Indigenous communities to further their right to fish in pursuit of a moderate livelihood by reaching understandings that authorize community members to fish under community-developed moderate livelihood fishing plans. Under Moderate Livelihood Understandings, communities identify community members who wish to fish in pursuit of a moderate livelihood under their community-developed plan and they are designated as authorized harvesters under a licence issued by DFO. Since 2021, the Department has reached interim understandings that have seen multiple First Nations fishing lobster under Moderate Livelihood Understandings, and selling their catch during the DFO established seasons, without increasing overall fishing effort. Multiple Rights Reconciliation Agreements have been reached with First Nations in the Atlantic provinces and in Quebec. The Department's priority continues to be the further implementation of treaty rights in a way that supports an orderly fishery and includes measures for conservation.

Lessons from previous ocean management initiatives

The MPC Program in the Maritimes Region has taken a “learn by doing” approach in meeting the oceans management commitments outlined in Canada's Oceans Act. When the IOM Program began in Canada over 20 years ago, there was little previous experience to draw from. Many lessons have been learned over this time, from the early work on the Region's Large Ocean Management Area on the Eastern Scotian Shelf, coastal management areas in the Bras d'Or Lake and Southwest New Brunswick, through the selection, designation and on-going management of the Gully, Musquash, and St. Anns Bank marine protected areas as well as other conservation areas, and the analysis and development of a regional conservation network. Considerable capacity has been developed over the years in several key areas that continue to support the Oceans Act mandate and help advance a marine spatial planning program. Additional past integrated oceans management initiatives are described in the Regional Oceans Plan (DFO 2014).

The MPC Program is the lead for marine spatial planning and has developed strong multidisciplinary capacity in the areas of:

- oceans and coastal management

- conservation planning

- engagement and collaboration

- decision support

- the analysis and use of spatial data and information including geographic information systems (GIS) and Marxan analysis

The development of knowledge, skills, and experience in policy, planning, and management has been instrumental given the multidisciplinary nature of the work. This has been supported by the need to facilitate work among the diverse interests involved in the marine and coastal environments, including:

- Indigenous communities and organizations

- other levels and departments of government

- industry

- academics

- conservation organizations

- coastal communities

This experience, and the structures and relationships created to support this engagement, remain invaluable.

Key lessons from these experiences are reflected in the current approach being advanced for the MPC Program. Included is the focus on working collaboratively, supporting the capacity of others to participate in manageable processes, increasing communication and transparency, and focusing on tangible outcomes including those related to supporting better planning and decision-making by the Government of Canada and others through the provision of timely and accessible information and tools.

Engagement approach

Effective engagement with partners and stakeholders is a key component of any MSP process to ensure an exchange of information and perspectives. This section describes the engagement approach taken by the Maritimes Region for the first-generation marine spatial plan, including the key organizations involved (see the list below). As the MSP Program in Canada is still developing, a key focus will be on future efforts. The goals of regional engagement on MSP in the short term include:

- communicate our regional approach to MSP (i.e., support for sector-based planning and management)

- demonstrate how to use the Canada Marine Planning Atlas and discuss data and information for MSP

- receive input on regional MSP priorities and scope to be reflected in the plan

- discuss what MSP processes and governance could look like in the future

Key participants to be involved in the MSP process in Maritimes Region

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Aquatic Ecosystems (led by the Marine Planning and Conservation Program)

- Science

- Policy and Economics

- Resource Management

- Communications

- Other DFO regions and National Headquarters (NHQ)

Federal departments

- Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)*

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC)*

- Transport Canada (TC)*

- Parks Canada Agency (PCA)

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency (ACOA)

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (IAAC)

*Federal departments that have received funding to support MSP.

First Nations

- Nova Scotia Mi'kmaw First Nations

- New Brunswick Mi'gmaq First Nations

- Wolastoqey Nation

- Peskotomuhkati Nation

Indigenous Organizations

- The Confederacy of Mainland Mi'kmaq -Mi'kmaw Conservation Group (MCG)

- Kwilmu'kw Maw-klusuaqn (KMKNO)

- Maritimes Aboriginal Peoples Council (MAPC)

- Unama'ki Institute of Natural Resources (UINR)

- Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick

- Migmawe'l Tplu'taqnn Incorporated (MTI)

Municipalities

- Various municipalities throughout Nova Scotia and New Brunswick

Stakeholders

- Marine industry sectors (various)

- Non-governmental organizations

- Academics

- Communities

Early engagement efforts have focused on federal, provincial, and municipal levels of government and Indigenous organizations. In 2023, focused internal engagement with regional DFO sectors was initiated. Throughout 2023 DFO continued to identify interests and priorities for MSP through external engagement with First Nations and Indigenous organizations, industry (i.e., fishing, aquaculture, energy), and environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs).

External engagement included sector-specific workshops with a range of topics, such as MSP products (the Canada Marine Planning Atlas and decision-support tools), MSP and conflict avoidance, and MSP in the future. Throughout the engagement process, Atlas tutorials to demonstrate how the tool can be used were offered. Communication products were distributed to provide a plain language explanation of MSP. More information on communications products can be found in the Improve communications section. As this work advances in the planning area, additional collaborative governance structures may be developed where necessary. Engagement will be an ongoing aspect of this process.

Indigenous engagement

DFO has worked to engage with First Nation and Indigenous organizations early in the MSP process so that their input could help shape the ideas, needs, and priorities of this first-generation plan. Engagement is focused on building upon previous experiences and existing relationships to support the advancement of MSP. DFO works through the Kwilmu'kw Maw-klusuaqn Negotiation Office (KMKNO) to engage with Nova Scotia First Nations. Engagement with New Brunswick First Nations occurs through the Mi'gmawe'l Tplu'taqnn Incorporated (MTI) and the Wolastoqey Nation of New Brunswick (WNB), and directly with the Peskotomuhkati. Contribution Agreements also support engagement efforts by providing First Nations and Indigenous organizations with an enhanced capacity to engage their own community members and DFO to undertake projects on relevant topics, including MSP and marine conservation. Contribution Agreements also strengthen the relationships between DFO staff and these communities through regular meetings and dialogue. These arrangements help to create a clearer understanding of each other's perspectives and roles.

DFO has also engaged with the Maritimes Aboriginal Peoples Council (MAPC) to share information on MSP and discuss their organizations' priorities and interests. DFO Maritimes typically engages with the Native Council of Nova Scotia (NCNS) and New Brunswick Aboriginal Peoples Council (NBAPC) by coordinating through MAPC. The Mi'kmaw Conservation Group (MCG) and Unama'ki Institute of Natural Resources (UINR) are involved in MSP in part through their participation in the KMKNO-DFO Aquatic Ecosystems Working Group.

Federal engagement

The focus of federal engagement for MSP is on:

- program development

- information sharing

- work planning

- priority development

- alignment of messaging and approaches.

Engagement with other federal departments on MSP occurs at the Atlantic Coordination Table (ACT).

Provincial engagement

Engagement on MSP with the Government of Nova Scotia is occurring through Provincial-DFO Aquatic Ecosystems bilateral tables, including both DFO Maritimes and Gulf Regions. DFO Maritimes Region leads coordination and agenda-setting with the Province through the Nova Scotia Department of Intergovernmental Affairs. Engagement with the Government of New Brunswick is coordinated through the New Brunswick Department of Intergovernmental Affairs and led by DFO's Gulf Region.

Municipal engagement

Municipal government engagement included workshops and discussions on MSP across the planning area where many municipal governments are located. These sessions served to introduce the concept of MSP and to get a preliminary sense of their capacity, interests, and priorities. Additional engagement was sought through workshops in the later part of 2023.

Industry and stakeholder engagement

DFO Maritimes Region engages with the industry and stakeholders through the groups listed below. Multi-sector information sessions were held as part of engagement sessions to ensure the involvement of additional groups.

Industry and stakeholder groups include:

- Southwest Fundy Progressive Protection Council

- Scotia-Fundy Fishing Sector Roundtable

- Commercial Species Advisory Committees

- Nova Scotia Fisheries Alliance for Energy Engagement

- Atlantic Groundfish Council

- DFO ENGO Forum

- Bay of Fundy Ecosystem Partnership

- Gulf of Maine Council

Governance

Meaningful and effective governance arrangements are required to ensure all parties can participate in, contribute to, and benefit from the MSP process. Within the Maritimes Region, several governance and institutional arrangements are in place to assist with this work. Additional arrangements will be considered as this work evolves and as deemed beneficial. Some of the current arrangements within DFO, with other federal departments, the provinces and Indigenous organizations are outlined in the list below.

- DFO Internal

- Senior Management and Directors

- Regional Operations Committee (Maritimes Regions, all DFO Sectors)

- Directors and Managers

- Regional Integration Committee (Maritimes Regions, all DFO Sectors)

- Managers and Project Leads

- MSP Working Group (Maritimes Regions, all DFO Sectors)

- Senior Management and Directors

- Federal

- Managers and Project Leads

- Atlantic Coordination Table for MSP (DFO-led: Mar, NL, NHQ, Gulf, TC, ECCC, PCA, IAAC)

- Managers and Project Leads

- Federal-Provincial

- Senior Management and Directors

- Bilateral Table with NS (DM, RDG level)

- Directors, Managers, and Project Leads

- NS-Canada Coordination Table (Federal: DFO-led, PCA, ECCC, NRCan; NS: IGA-led, include: DFA, EBCC, NR&R)

- Fed/Prov Ad-hoc Coordination Table

- Federal: DFO (Gulf-led, Maritimes)

- NB: IGA-led (NB agency participation as required)

- Senior Management and Directors

- Federal-Indigenous

- Senior Management and Directors

- Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn (KMK)-DFO Consultation Table

- Directors, Managers, and Project Leads

- Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn (KMK)

- DFO Aquatic Ecosystems Working Group

- Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn (KMK)

- Senior Management and Directors

Other governance arrangements have developed within the DFO Maritimes Region planning area to support more sub-regional or site-specific work. One example includes the work of the Bras d'Or Lake Collaborative Environmental Planning Initiative which has been a partnership of the Indigenous, federal, provincial and municipal governments, local NGOs, academics, industry, and community members. Another such arrangement is the Minas Basin Working Group which is helping coordinate research in this important ecological area.

Sub-regional highlight: The Bras d'Or Lake

The Bras d'Or Lake in Nova Scotia is a unique estuary at the heart of Cape Breton Island. The estuary, coastal waters, and numerous freshwater rivers and streams have sustained generations of people, beginning with the Mi'kmaq, whose growing communities continue to rely on its natural resources and culturally important areas. In recent years however, the health of the Bras d'Or has diminished from anthropogenic pressures such as overfishing, the introduction of invasive species, the impacts from forestry, sewage inputs, and unsuitable land development practices. To help address these concerns, the Bras d'Or Collaborative Planning Initiative (CEPI) has been in place as a partnership between Indigenous, federal, provincial, municipal governments, NGOs, industry, academics, and community members. Numerous studies and projects have been undertaken through this partnership within the Bras d'Or to better understand its conditions and address these concerns. Work is ongoing and led by the Unama'ki Institute of Natural Resources (UINR) that represents the First Nations in Cape Breton and who play the secretariate and convenor role for this group of interested collaborators.

Further information can be found on the Bras d'Or CEPI website.

Goals

The current marine spatial planning approach aims to add value to the existing ocean and coastal management regime within the planning area. In doing so, 2 specific goals are being pursued – improved planning and improved decision-making

These goals are supported by specific objectives within the MSP process as illustrated in the list below.

Improved planning

Marine spatial planning processes are about the future. The following questions and many others must be addressed through a process to plan a desirable future:

- what activities, locations, levels of use, and environmental conditions are desirable

- are different groups and organizations able to have a say in this future

- what trends are observed

- what tradeoffs or compromises are needed

- do we have the right information

- if commitments are made in planning, how will they be enforced

- how will climate change affect our planning

These questions and many others must be addressed through a process to plan a desirable future. While the plans developed under MSP are not regulatory in nature or enforceable under the Oceans Act, they should help influence the efforts and decisions of each partner that contributed to it.

Improved decision-making

Figure 6. The marine spatial planning process.

Long description

The image is a diagram of the process of marine spatial planning (MSP). MSP is a complex process that involves planning and managing the use of marine areas to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives. The diagram outlines the steps involved in the MSP process, which are broken down into 4 sections: participants, process, plans and decisions, and outcomes.

Participants in MSP include:

- Government:

- Indigenous

- Federal

- Provincial

- Municipal

- Marine users:

- fishing

- shipping

- energy

- cables

- tourism

- recreation

- aquaculture

- coastal development

- conservation and others

Process: The process section outlines the steps taken to develop an MSP plan. The diagram shows that the marine spatial planning process provides information and tools, analysis, coordination, governance, participation, and communication

Plans and decisions: Plans and decisions relate to approvals, assessments, funding, research, investment, development, siting, and other topics

Outcomes: The outcomes are the products of the MSP process. Outcomes include environmental, economic, social/ cultural, and institutional

The second goal for the MSP process is improved decision-making. Improved decision-making is being pursued to help realize the vision and priorities outlined through the planning process and fulfill the legislative mandates of many different organizations. The first-generation Plan is not a zoning scheme as is often associated with MSP. Instead, the Plan aims to add value to the numerous decisions that are associated with the management of the marine environment by a diverse range of users and regulators. These decisions may be improved by better or more accessible information, broader perspectives, or decision-support tools for specific issues.

Goals and objectives of the MSP program in Maritimes Region

Objectives for improved planning:

- develop a clear framework for MSP

- balance social, cultural, economic and environmental considerations

- set priorities (seek tradeoffs)

- be adaptable (to address issues such as climate change)

Objectives for improved decision-making:

- develop knowledge products and decision-support tools

- coordinate and streamline decision-making

- seek policy and legislative improvements

- understand and consider cumulative impacts

Common objectives for both:

- share data and knowledge products

- ensure effective participation

- improve communication

Both government and marine users participate in marine spatial planning processes through various mechanisms where information, tools, coordination, and communication products help support and improve existing plans and decision-making processes. These plans and decisions result in specific outcomes which may in turn influence the government, partners and marine users in a manner as shown in Figure 6. Marine users and government can use MSP to help improve their planning and decision-making processes, whose outcomes in-turn influence these marine users and governments.

Objectives

The objectives outlined in this section will help achieve the goals of this first-generation marine spatial plan. Efforts to meet each of these objectives will form part of future MSP implementation activities. Practical benefits associated with MSP and linkages to the objectives of this plan are outlined in the Table below.

| Key benefits of MSP | MSP objectives |

|---|---|

| Supporting economic opportunities |

|

| Reducing conflicts with siting new activities |

|

| Improving awareness and understanding of ocean issues |

|

| Valuing and including multiple perspectives and knowledge systems |

|

| Planning at local to regional scales |

|

Develop a framework for marine spatial planning

Figure 7. DFO's adaptive approach to marine spatial planning.

Long description

The image is a diagram showing the 6 phases of the marine spatial planning process (MSP) created by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). The text at the top of the diagram clarifies that the phases are not necessarily linear and can be adapted depending on the specific circumstances.

The 6 phases are listed from top to bottom as follows:

- Getting Ready: This involves building on past ocean initiatives, identifying who should be involved in MSP, and identifying strategies to advance MSP.

- Gathering Information: This phase focuses on integrating information from various sources and creating insights on the planning area, including how it’s used and managed.

- Building Partnerships: This phase involves working collaboratively to identify the roles of those involved in MSP and defining a shared vision for MSP, its priorities, and desired outcomes.

- Envisioning Scenarios: This phase involves building scenarios for the future of the planning area, and reaching consensus on the preferred scenario.

- Making a Plan: This phase involves developing a shared marine spatial plan.

- Implementing a Plan: This phase involves working collaboratively to implement measures.

The bottom of the diagram emphasizes that the MSP is a cyclical and evolving process that should be monitored, evaluated, and adapted over time. This adaptive process allows for learning and making changes as stakeholders work together towards sustainable use of the shared ocean environment.

For DFO to support the advancement of MSP, a framework is required to explain the scope and approach being taken, and the possible outcomes for those involved. This first-generation marine spatial plan is the framework for the Scotian Shelf and Bay of Fundy planning area.

DFO's National Guidance for Marine Spatial Planning (DFO 2024a) has helped provide the support for these plans in Canada. It has been based on international guidance developed by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission under the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and broadly reflects the vision of Canada's Oceans Strategy. MSP practitioners and managers are given a basic outline to support discussions with partners about the marine spatial planning process and what should constitute the plan's key elements. The National Guidance document outlines the general components for the first-generation marine spatial plans in Canada including the general activities illustrated in Figure 7.

The DFO National Guidance provides an outline for these MSP frameworks in Canada. It should be noted that this current first-generation plan only reflects the initial stages of this MSP process. Future efforts may pursue additional stages while supporting ongoing work from the first stages.

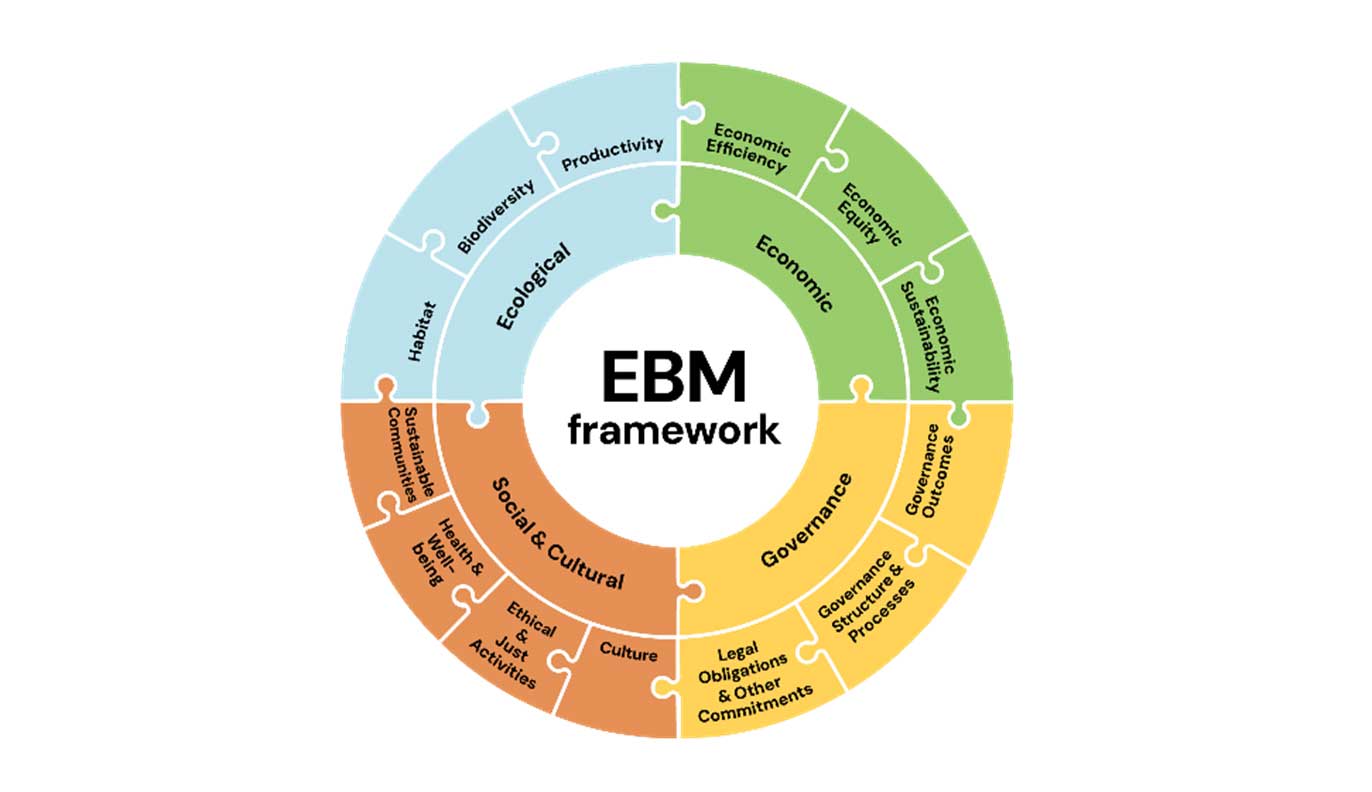

Balance social, cultural, economic and environmental considerations

As outlined in the introduction, MSP is an approach to management that aims to support a range of social, cultural, economic, and environmental considerations for a specific area. Ocean governance and management approaches that focus on a single sector, species, or activity do not account for the cumulative impacts of multiple uses. As an integrative approach to management, MSP attempts to consider the entire ecosystem, including human uses that are for economic, social, and cultural purposes. MSP can be used to assess conflicts between human uses, and between human uses and environmental components, and be a venue to discuss and analyze tradeoffs while aiming to maximize benefits for all involved.

To achieve a balance between social, cultural, economic, and ecological considerations within the planning area, engagement with ocean users is required to ensure that different perspectives, interests, and priorities are reflected in the marine spatial plan. As well, social, cultural, economic, and environmental data and information from the planning area is being sought for the MSP decision-support tools and mapping products, such as the Canada Marine Planning Atlas, the Maritimes Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) Framework, and the Strategic Ecosystem/Activity Compatibility Assessment Tool. These, as well as any tools developed in the future, provide analysis of human use and ecosystem components in the planning area with the intent of improving decision-making and planning. For example, this approach to planning will be able to identify areas in need of conservation and protection (i.e., the marine conservation network plan), along with areas suitable for development and other human uses. The ability to balance social, cultural, economic, and environmental objectives throughout the MSP process depends on the degree of involvement from many regulators, rights holders, user groups and citizens.

Socio-economic considerations in MSP

Robust information is needed to consider social, cultural, economic, and ecological objectives related to MSP. Environmental and economic information is typically included in MSP processes. While social and cultural considerations are primarily received through consultation and engagement activities, broader socio-cultural factors (e.g., well-being, equity, social connections to nature) are generally not analyzed due to a lack of data and internal social science research capacity. In 2021, a research report was developed for DFO that outlines best practices for including this information in MSP processes, focusing on the current planning area (Amos 2021).

The report describes opportunities for incorporating social, cultural, and economic information in the MSP process. Key points include:

- Socio-economic factors should be considered in assessing the need for MSP

- Socio-economic components should be considered throughout the MSP process, from budget to establishing an MSP team, developing the workplan, data collection, analysis and decision-making

- Stakeholder engagement is key to meaningfully incorporating social and cultural information into spatial planning

- Data collection approaches should be tailored to the MSP approach and the context. Common approaches include compiling third-party data and/or observational data, consulting experts, conducting public consultations, focus groups and/or workshops and facilitating participatory approaches

- Data analysis tools can be categorized as economic valuation tools, spatial analysis tools and social impact assessments. The type of analysis used depends upon the previous steps in the MSP process

The author used 4 case studies to illustrate different approaches to including socio-economic information in MSP: Moray Firth in Scotland, England South Inshore and South Offshore Marine Spatial Plan, Raja Ampat MPA Network, and Haida Gwaii Marine Plan

Set priorities

MSP can provide the benefit of a consistent approach for a planning area based on common priorities. In the early stages of this process, partners will be engaged to clarify and share their priorities. Future goals, objectives, and targets can then be developed which support this vision. Participants will be engaged to understand whether this vision reflects their respective priorities; this engagement will be repeated regularly to ensure the process is relevant to changing interests and needs.

Through the identification of common priorities, a shared approach can be developed that reflects a range of interests. From this, work plans can be developed collaboratively to achieve these outcomes.

Be adaptable

The MSP process must be adaptable to the realities of a changing world. Change will come in several different forms, ranging from changes in the knowledge of the natural environment to changes in the economic priorities of different activities, to changes in social and cultural importance placed on distinct aspects of our coastal and marine areas. Climate change is bringing about overarching shifts that affect all aspects of the planning area. Being adaptive to refocusing priorities, having governance mechanisms to continually engage and discuss views, updating environmental, social, and economic data, products, and maps, and revisiting the plan regularly, will allow it to reflect the latest knowledge and perspectives required to adapt to climate change.

Climate change

Building a better understanding of the effects of climate change, the impacts of human activities, and the natural processes that drive our oceans will be essential for evidence-based decision-making and effective planning. Ongoing research of the marine environment will help improve management and conservation measures and assess how Canada is meeting its goals under the Global Biodiversity Framework Target 8 as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity.

Target 8: Minimize the Impacts of Climate Change on Biodiversity and Build Resilience

“Minimize the impact of climate change and ocean acidification on biodiversity and increase its resilience through mitigation, adaptation, and disaster risk reduction actions, including through nature-based solution and/or ecosystem-based approaches, while minimizing negative and fostering positive impacts of climate action on biodiversity.”

- Convention on Biological Diversity

Develop knowledge products and decision-support tools