Violet Tunicate

Botrylloides violaceus

Report it

If you think you have found an aquatic invasive species:

- do not return the species to the water

- take photos

- note:

- the exact location (GPS coordinates)

- the observation date

- identifying features

- contact us to report it

On this page

- Origin and distribution

- Identifying features

- Ecological and economic impacts

- Mode of arrival

- Mode of dissemination

- Government action

- Violet Tunicate in Newfoundland

- For further information

- References

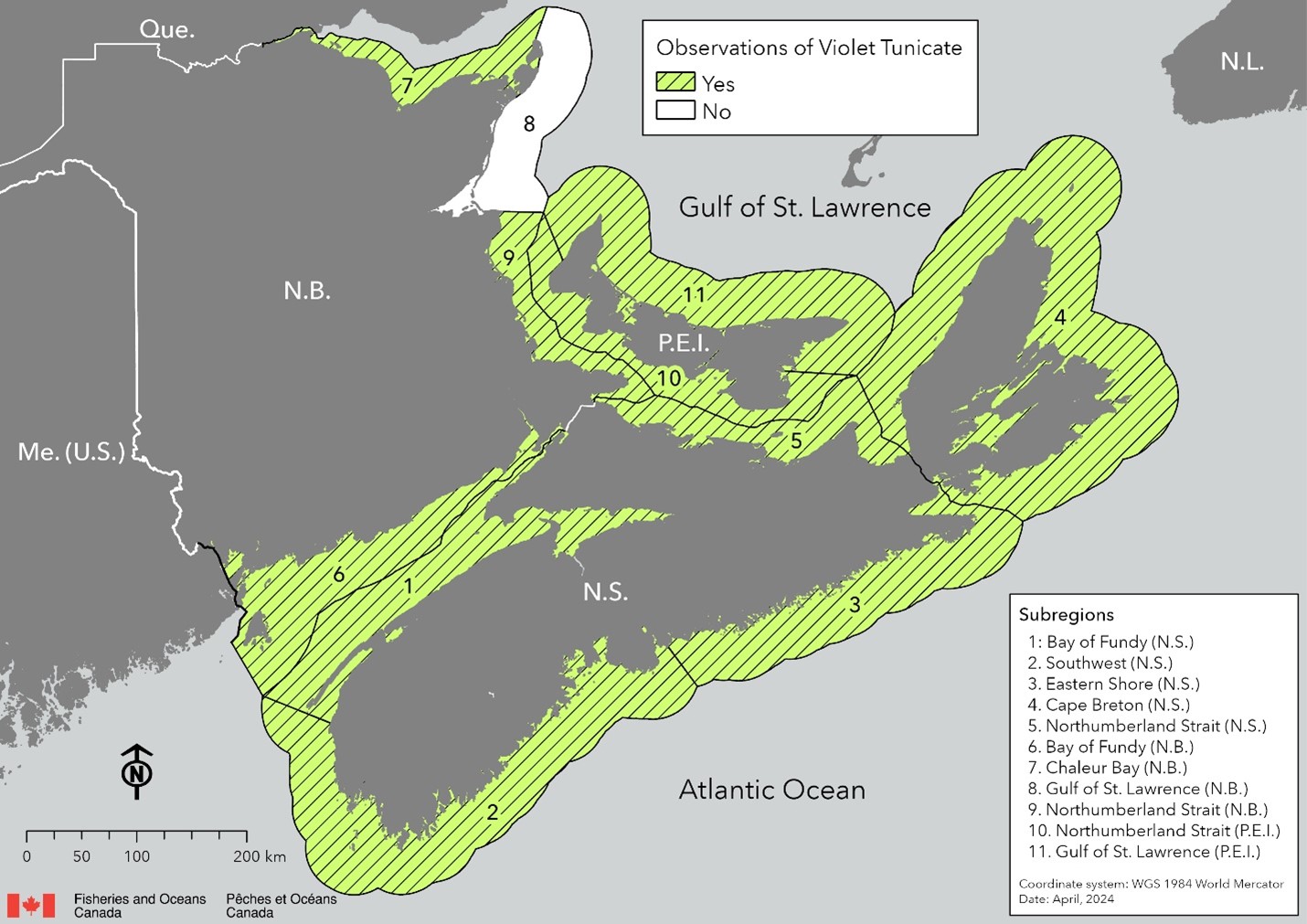

Origin and distribution

Violet Tunicate is an invasive colonial tunicate native to the northwestern Pacific ocean (east Asia). The Violet Tunicate was first observed in eastern Canada on the:

- Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia in 2001

- Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2002

- south coast of Newfoundland in 2007

- New Brunswick coast of the Bay of Fundy in 2009

It is now widely distributed in:

- Prince Edward Island

- Nova Scotia

- along the south coast of New Brunswick

- in some areas of eastern New Brunswick

In British Columbia, this colonial species is widely distributed, with reports from:

- Strait of Georgia

- West Coast of Vancouver Island

- North Coast

- Haida Gwaii

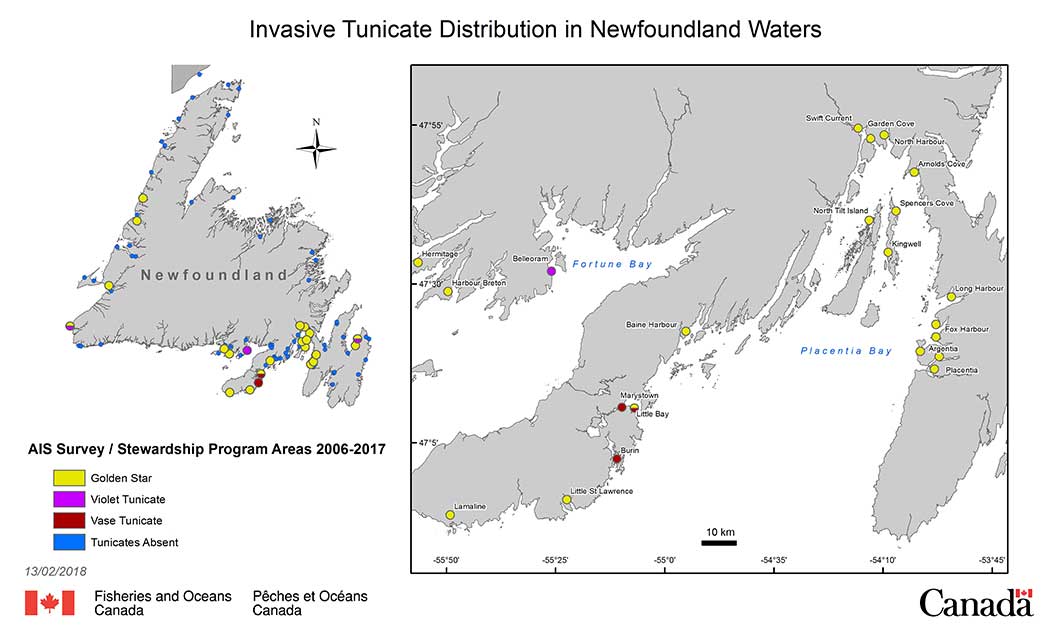

Observed distribution of Violet Tunicate in subregions of Canada’s Maritime provinces.

Note: Observation within a subregion does not mean the species is found throughout it. Lack of observation within a subregion does not mean the species is absent from that subregion. It means that it has not been observed there.

Identifying features

- Dense colonies of many small (2 to 4 millimetres) individuals

- Individuals within the colony may be distributed randomly or in a network of curving tracks

- Colour variable: whitish, yellow, orange, reddish-brown, violet

- Colony size often reaches 10 centimetres

Similar species (native)

Violet Tunicate can be mistaken for sponges, but sponges have a soft porous texture rather than a gelatinous one.

Violet Tunicate can be distinguished from other colonial tunicate species by the apparently random arrangement of individuals. They have distinct ridge or track-like patterns on the surface of their fleshy coat. Violet Tunicate has fewer colour patterns than Golden Star Tunicate and is typically evenly coloured in shades of:

- whitish

- yellow

- orange

- reddish-brown

- violet

Ecological and economic impacts

Violet Tunicate is a filter feeder, getting nutrients from phytoplankton (algae), bacteria and other small organic things that float in the sea. In large numbers, the tunicate competes for food with other filter feeders, such as mussels and scallops.

Violet Tunicate is mostly composed of water. It grows rapidly compared to other marine organisms. It may cover surrounding plants and animals and deprive them of sunlight or food. Violet Tunicate may even suffocate smaller organisms, such as juvenile mollusks. It releases a chemical that can make it hard for other organisms to attach properly to surfaces. These organisms then become vulnerable to being removed by water currents. This chemical can also repel and inhibit growth in predators. All of this makes the Violet Tunicate harmful to:

- shellfish harvesters

- aquaculture farmers

- aquatic organisms that live on the bottom of the ocean

Mode of arrival

Violet Tunicate was most likely introduced to North America through hull fouling and/or fragments in ballast water.

Mode of dissemination

The lifecycle of Violet Tunicate is not fully understood, but we know that they can reproduce in 2 ways:

- when fragments of a colony break off and bud elsewhere

- by the production of eggs which hatch into free-swimming larvae

Colony fragments may travel over great distances and the fragments are able to reproduce for up to 40 days. Larvae released into the water column settle within 48 hours, and only travel small distances.

Government action

Scientific research

Fisheries and Oceans Canada is monitoring the distribution of invasive biofouling species (that is, aquatic species that live attached to hard surfaces) on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts to detect new invasions and track the spread of Violet Tunicate.

Controlling abundance

Tunicates can spread through the movement of:

- fishing gear

- shellfish

- recreational and commercial vessels

To prevent the spread of Violet Tunicate, boats and other gear should be visually inspected and properly cleaned, drained and allowed to dry for 7 days. Also, because Violet Tunicate can rapidly colonize and establish large, self-sustaining populations, it should be removed from wharves and surrounding structures.

Violet Tunicate in Newfoundland

Discovery and survey findings

During a survey in September 2007, Violet Tunicate was discovered in Belleoram, Fortune Bay in Newfoundland. This is a concern to the aquaculture industry in Newfoundland. However, this species has not yet been found in local mussel farms. Fortunately, its distribution appears to be restricted to Belleoram where it is being found on:

- wharf structures

- ship hulls

- plastic surfaces

- rocks

- wild mussels

This species still poses a potential risk to bottom dwelling aquatic animals in other parts of Newfoundland and Labrador so it is important to continue to monitor other areas. This will help in the long-term management and prevention of the spread of Violet Tunicate.

In 2008-2009, Fisheries and Oceans Canada worked with Memorial University of Newfoundland to test various mitigation methods in Belleoram. This included wrapping wharf pilings and covering affected rocks and structures with plastic. While this killed many Violet Tunicates, they eventually came back and resettled in large numbers on and around the treated surfaces. As of 2010, other methods of prevention and control are being tested, including the introduction by Fisheries and Oceans Canada of sea urchins to the Belleoram wharf. Sea urchin eat Violate Tunicate and the department is studying whether the sea urchins will control the population through predation.

Continuing survey and monitoring work will improve our understanding of the Violet Tunicate. Understanding an organism's lifecycle in its newly invaded environment helps us to establish where and when to target prevention and control efforts. It is especially important that we understand how Violet Tunicate over-winter and when they sexually reproduce. When combined with surveys, using genetic tools to find eggs and larvae of Violet Tunicate will help us target our efforts.

For further information

- Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Publications

- Invasive Tunicate - Fact Sheet

- Biological Synopsis of the colonial tunicates, Botryllus schlosseri and Botrylloides violaceus (PDF, 1,162 KB) Fisheries and Oceans Canada – 2006

- Aquatic Invasive Species: Violet Tunicate in Newfoundland and Labrador Waters Fisheries and Oceans Canada - 2011

- Science advice from a risk assessment of five sessile tunicate species (CSAS SAR - 2012/049)

References

Berrill, N.J. 1950. The Tunicata, with an account of the British species. Ray Society, London. Publication 133: iii + 354 p.

Callahan, A.G., Deibel, D., McKenzie, C.H., Hall, J.R., et Rise, M.L. 2010. Survey of harbours in Newfoundland for indigenous and non-indigenous ascidians and an analysis of their cytochrome c oxidase I gene sequences. Aquat Inv 5: DOI 10.339/ai2010.5.1.

Lambert, C.C. et G. Lambert. 2003. Persistence and differential distribution of nonindigenous ascidians in harbors of the Southern California Bight. Mar Ecol Prog Ser, 259:145-161. Oka, A. 1927. Zur kenntnis der japanischen Botryllidae (vorlaufige Mitteilung). Proc Imp Acad, 3: 607-609.

Van Name, W.G. 1945. The North and South American ascidians. Bull Am Nat Hist, 84 p.

- Date modified: