The baitfish primer

A guide to identifying and protecting Ontario's baitfishes

by Becky Cudmore and Nicolas E. Mandrak

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Summary of legislation and regulations related to baitfishes

- Potential impacts of harvest and use of baitfishes

- Baitfish habitat

- Anatomical key

- Pictorial key of Ontario fish families

- Species accounts

- What you can do to minimize impacts to aquatic ecosystems

- Further reading

- Contacts

Introduction

Recreational angling is a popular pastime in Ontario - well over one million residents and visitors enjoy angling every year. Angling supports many aspects of the Ontario economy, including the baitfish industry. Many anglers use live bait, including baitfishes. Few anglers probably realize that there are over 40 species of legal baitfishes in Ontario. Too many, all small fishes look alike; however, upon closer inspection, most baitfish species can be distinguished from one another with relative ease. If you can tell a House Sparrow apart from a Black-Capped Chickadee, then (with practice) you will soon be able to distinguish a Creek Chub from a Longnose Dace!

The ability to distinguish among small fish species is important, as the use of many species for bait is illegal. It is discouraged, and often illegal, to use sport fishes, introduced (non-native) fishes, or fish species that are so rare that their use may lead to further declines and possible extinction. Even within fish families generally considered legal baitfishes, there are individual fish species that cannot be used.

Individual fish species may become illegal for baitfish use for various reasons:

- they are listed as Extirpated, Endangered, Threatened, or Special Concern under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) or the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)

- they are listed as invasive under federal or provincial legislation and regulations; and/or

- they are not included on the allowed baitfish species list in the Ontario Fishery Regulations, 2017 (OFRs)

Additionally, there are species that require caution for use as baitfishes, as they are species that, although legal, can be easily confused with illegal species.

Baitfishes may be collected by individuals possessing a resident fishing licence, or by licensed commercial baitfish harvesters. Areas supporting extirpated, endangered or threatened species at risk fishes listed on schedule 1 of SARA or identified on national aquatic species at risk maps should be avoided. If any species at risk are encountered during baitfish collection they should immediately be released alive in the location they were found. The commercial baitfish industry in Ontario is comprised of over 1,100 licensed harvesters and dealers. The bait resource and industry is managed by the province through licensing, legal species lists, log books, annual reporting and best management practices. In addition, harvesting takes place in prescribed geographic areas and is based on principles intended to protect baitfishes and their habitat into the future.

It is imperative that all commercial and recreational baitfish harvesters are aware of, and adhere to, all federal and provincial laws and regulations pertaining to this activity. In addition, all baitfish users should understand the potential impacts of the careless collection, use, and disposal of baitfishes to minimize or eliminate such impacts.

By the end of this Primer, you will:

- understand the federal and Ontario legislation and regulations pertinent to the use of baitfishes

- be able to identify small fish species

- be able to distinguish between legal and illegal baitfishes

- recognize the importance of baitfish habitat

- understand the potential impacts of improper baitfish use; and,

- understand how to minimize negative impacts to our aquatic ecosystems

Acknowledgements

The help and direction provided by Harold Harvey (University of Toronto) was invaluable in the production of this Primer. The authors would also like to thank the following for their input and assistance: Karen Gray, Debbie Ming, Jason Barnucz, Andries Blouw, Andrew Drake, Theresa Nichols, Todd Morris, Shawn Staton, Heather Surette, Hilary Prince, and Timothy Gingera (Fisheries and Oceans Canada); E.J. Crossman and Erling Holm (Royal Ontario Museum); Debbie Bowen and Doug Jensen (Minnesota Sea Grant Program); Chris Brousseau, Alan Dextrase, Beth Brownson, Scott Gibson, Mark Robbins, Derrick Humber, David Copplestone, and Brenda Koenig (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry); Madolyn Mandrak (University of Guelph); and Dustin Boczek.

Illustration credits:

- University of Minnesota Sea Grant Program: Rusty Crayfish

- Bonna Rouse, Allset Inc.: Front cover and general non-species specific illustrations

- Joseph R. Tomelleri: Black Redhorse, Blackstripe Topminnow, Bluntnose Minnow, Eastern Sand Darter, Fantail Darter, Ghost Shiner, Gizzard Shad, Gravel Chub, Greenside Darter, Johnny Darter, Lake Chubsucker, Least Darter, Mottled Sculpin, Ninespine Stickleback, Pugnose Minnow, River Darter, River Redhorse, River Shiner, Round Goby, Ruffe, Silver Chub, Silver Shiner, and Spotted Sucker

- Carlyn Iverson, Absolute Science Studios: Black Carp, Tench, and Tubenose Goby

- Emily S. Damstra: Bighead Carp, Grass Carp, and Silver Carp

- New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC), Bureau of Fisheries, Albany, NY: All other fish illustrations found in The Baitfish Primer

Summary of legislation and regulations related to baitfishes

Ontario Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act

Capture of baitfishes

Anglers: Residents with a valid recreational fishing license issued under the Ontario Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act (FWCA) may capture their own baitfishes for personal use using traps and dipnets following all conditions in Ontario's Recreational Fishing Regulations Summary. The Ontario Fishery Regulations, 2007 (OFRs) allows them to set a legal minnow trap (no more than 51 cm × 31 cm; labelled with name and address of owner) or capture fishes with a dipnet (no more than 183 cm in diameter or along each side, and during daylight hours only). The capture and use of bait is not allowed in some waters; the latest version of the Ontario Recreational Fishing Regulations Summary should be consulted for Zone regulations and exceptions. Baitfishes may be caught for personal use only and anglers must have no more than 120 baitfishes in their possession at any time, which includes both caught and purchased baitfish. Any live holding box or trap must be clearly marked with the name and address of the user, and must be visible without raising it from the water.

Commercial Bait Harvesters: The taking, transporting, buying and selling of baitfishes is authorized for the holder of a commercial bait licence issued by the province under the FWCA and in keeping with the requirements under the OFRs and FWCA. The means of taking baitfishes may be specified on the individual commercial bait licence. Licensed harvesters or dealers are required to record harvest and/or maintain receipt of baitfishes in log books and submit annual reports.

Use of baitfishes

Anglers can find a complete up-to-date listing of which fish species can be used as live baitfish in the OFRs.

Species listed as invasive fishes under the OFRs cannot be possessed alive. The use of bait is prohibited in some waters. No crayfishes, salamanders, live fishes or live leeches can be brought into Ontario for use as bait. It is illegal to release any live bait, or dump the contents of a bait container (including the water) into any waters or within 30 m of any waters.

In addition, fishes listed as Extirpated, Endangered, Threatened or Special Concern under either the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) or the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007 cannot be used as baitfishes. Species considered sportfishes cannot be used as live bait.

The legal status of baitfish species may change over time. Be sure to check the latest version of the Ontario Recreational Fishing Regulations Summary for up-to-date information. Go to Fishing with live bait.

Federal Fisheries Act

In Canada, this Act makes it unlawful to carry out any work, undertaking or activity that results in serious harm to fish that are part of, or support, a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery, unless authorized by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Serious harm to fish is defined in this Act as the death of fish or any permanent alteration to, or destruction of, fish habitat.

Website: Fisheries Act.

Federal Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations

In May 2015, Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations were added to the federal Fisheries Act to prevent the importation and spread of aquatic invasive species. Under the regulations, the importation, possession, transport, and release of listed species is prohibited unless they are dead and, in some cases, eviscerated (gutted).

Website: Aquatic Invasive Species Regulations

Federal Species at Risk Act

The federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) came into force in June 2004, and aims to protect native wildlife at risk, including fishes, from becoming lost from the wild, to provide for their recovery and to manage species of special concern. Under Section 32 of SARA, general prohibitions apply to fishes designated as extirpated, endangered or threatened. Fishes designated as such cannot be killed, harmed, harassed, captured, taken, possessed, collected, bought, sold or traded and the habitat that has been deemed vital to their survival or recovery is also protected. Areas supporting extirpated, endangered or threatened species at risk fishes listed on schedule 1 of SARA or identified on national aquatic species at risk maps (dfo-mpo.gc.ca/species-especes/sara-lep/map-carte/index-eng.html) should be avoided. If any species at risk are encountered during baitfish collection they should immediately be released alive in the location they were found. The list of species on schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act can be accessed on the following website below.

Website: Species at Risk Act

Ontario Invasive Species Act, 2015

In November 2015, the provincial Invasive Species Act, 2015 (ISA) came into effect in Ontario to prevent and control the spread of invasive species in the natural environment. The Act includes a list of prohibited species not established, and restricted species established, in the province that are illegal to possess, transport, or release.

Website: Ontario Invasive Species Act.

Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007

In June 2008, the provincial Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) came into effect in Ontario to protect at risk species and their habitats, to promote the recovery of species that are at risk, and to promote stewardship activities to assist in the protection and recovery of species that are at risk. Endangered, threatened or extirpated species, and their habitats, receive legal protection under the ESA. The Act calls for the creation of recovery strategies for endangered and threatened species, and management plans for special concern species.

Website: Ontario Endangered Species Act

Potential impacts of harvest and use of baitfishes

Harvesting may impact the ecosystems from which baitfishes are taken (termed donor ecosystems) and the ecosystems in which baitfishes are used (termed recipient ecosystems).

Impacts on donor ecosystems

Since the early 1900s, there were concerns regarding the depletion of the baitfish supply, followed by concerns about the declining numbers of sportfishes as a result of forage fish depletion. If carried out carelessly, baitfish harvesting may directly alter the abundance of targeted (legal baitfishes) and non-targeted (illegal baitfishes, such as game, invasive, or at-risk species) species in the donor ecosystem. Removal of a substantial number of legal baitfishes could potentially have short- and long-term effects on the abundance of forage fishes. To minimize such impacts, bait harvest areas are assigned to specific commercial licensees who manage the resource for sustainability. Commercial bait harvesters accomplish this by cycling harvesting locations within their bait harvest area, so that no one location is overharvested. Resident anglers should follow this practice as well to help ensure sustainability of the resource.

Care should be taken to safely return non-targeted species (other than invasive fishes) to the water immediately. If non-targeted species are not immediately returned, these populations could suffer an increased mortality, which may alter species interactions within that ecosystem. Such alterations may result in changes in species composition, increases in invertebrate (e.g., crayfishes) size and abundance, and decreases in productivity, abundance and growth rates of other fish species (including sportfishes).

Depletions in baitfish populations may also impact native freshwater mussels. Mussels have a complex life cycle that requires attachment when very young to a host, usually a fish. If large numbers of baitfishes are removed and the number of potential hosts decreases, mussel populations may decline.

The techniques used to harvest baitfishes may impact the habitat that all aquatic organisms (including baitfishes) depend on for the necessities of life. Baitfishes are typically harvested using seine nets or traps. Seining has greater impacts on habitat, as it is an active method that may cause uprooting of aquatic vegetation, removal of woody debris, and disturbance of bottom substrates - all important habitat components required by aquatic organisms for survival.

Traps leave a smaller ecological footprint. This technique is more passive, resulting in smaller disturbance to the surrounding habitat. Many commercial bait harvesters use traps, especially in vegetated areas. Traps and dipnets (which also have minimal impacts) are the only harvesting methods allowed to be used by resident anglers.

Impacts on recipient ecosystems

The impacts of fishes (baitfishes and other species) illegally released into recipient ecosystems have been well documented and can be summarized in four categories.

- Food-web changes: Introduced species have been shown to negatively impact food webs - the links between predators (e.g. sportfishes) and prey (e.g. baitfishes). Introduced fishes, such as the Round Goby, can out-compete native species for food and other resources, or even prey on native species and their eggs. These impacts may reduce the abundance of native prey that would, in turn, reduce the abundance of the sportfishes dependent upon these prey species for food.

- Habitat changes: The behaviour of introduced species can cause changes to habitat. For example, the destruction of aquatic vegetation and increased turbidity caused by the feeding and spawning of the Common Carp is well documented. Native species relying on that habitat would be greatly impacted by such changes.

- Introduction of disease: Diseases and parasites may be transferred to native species through introduced species. Exposure to these diseases or parasites may lead to decreased abundance of native species. The spread of “whirling disease” from stocked trout to wild trout is an example of this problem. The spread of disease may occur through baitfish transfer; however, the extent and impact of such transfers is not well understood.

- Genetic impacts : Native species are well adapted to their environment. Introduced individuals, not adapted to their new environment, may spawn with native individuals of the same species. Their offspring may look the same, but be less adapted to their environment. Introduced individuals may also spawn with native individuals of closely related species. Their offspring, termed hybrids, may be less adapted to their environment, or may be unable to reproduce. In most cases, spawning between introduced and native species will lead to the decreased abundance of native species.

These impacts are not limited to introduced baitfishes. The water in bait buckets may also carry microscopic invasive species, such as Spiny Waterflea, Fish Hook Waterflea, and Zebra Mussel larvae. These invasive species also have harmful impacts on our aquatic ecosystems.

Anyone with information about the unlawful movement of live fishes or the unlawful stocking of fishes, is encouraged to call the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry resource violation reporting line at 1-877-TIPS-MNR (847-7667).

Anyone finding species that they suspect are invasive should remove and freeze them, and report their finding to the toll-free Invading Species Hotline at 1-800-563-7711. The Hotline is a partnership of the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry.

Baitfish habitat

Importance of baitfish habitat

Baitfishes, like all fishes, require a place to meet their needs for food, shelter, and reproduction throughout their entire life. Although habitat requirements may be different for each stage in the life cycle of baitfishes, it is important that all needs are met. If, as a result of habitat degradation or loss, one or more of these requirements are not met at any point during their life cycle, their numbers will drop and the population may die out. The abundance of baitfishes is directly related to the quality of their habitat. Therefore, baitfishes can act as indicators of the environmental health of their habitat. A healthy baitfish population provides an important food source for many fish species, including commercial and sport fishes. By providing baitfishes with habitat that includes clean water, adequate food supply, cover, appropriate spawning and rearing grounds, and accessible migration routes, we safeguard these important resources for the baitfish, commercial, and sport industries, and also to help ensure a healthy ecosystem.

Some threats to baitfish habitat

Many of our actions threaten baitfish habitat. For example, agricultural and forestry activities can affect the quality and quantity of aquatic habitat through damage to in-stream habitat and the introduction of silt and other harmful materials into the water. General construction activities, such as building bridges and culverts, may also affect physical habitat and water quality, as well as impede movement of baitfishes among different habitats.

Other activities along shorelines, such as erosion control projects, marina developments and vegetation removal, may impact baitfish habitat by altering the natural cover and substrates of shoreline habitat. Changing water levels due to climate change and water-taking activities also directly affect the quality and quantity of baitfish habitat.

Protecting baitfish habitat

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has developed a webpage to provide advice and guidelines on environmentally sound practices when working in and around water. The ‘Projects Near Water' webpage provides common measures and best practices to avoid and reduce, or eliminate, impacts to fishes and fish habitat.

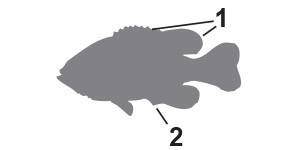

Anatomical key

Pictorial key of Ontario fish families

Fish families featured in the baitfish primer

- Numbered lines relate to anatomical features characteristic of the fish family

Salmons, trouts, and whitefishes (Salmonidae)

- adipose fin

- no spines

- small triangular flap at base of pelvic fin

New world silversides (Atherinopsidae)

- small, upturned mouth on long snout

- two widely-separated dorsal fins (first very small with spines)

- long, sickle-shaped anal fin

Topminnows (Fundulidae)

- flattened head and back

- upturned mouth

- single dorsal fin located far back on body

Sticklebacks (Gasterosteidae)

- three to nine isolated dorsal spines in front of dorsal fin

- extremely narrow caudal peduncle

Sculpins (Cottidae)

- one to four spines at rear margin of cheek

- large fan-like pectoral fins

- large head

- body tapering to narrow caudal peduncle

Fish families NOT featured in The Baitfish Primer as there are no members considered legal baitfish. Members of these fish families can be easily distinguished from legal baitfishes.

Lampreys (Petromyzontidae)

- scaleless body

- round, disc-like mouth without jaws

- no pectoral or pelvic fins

- seven pairs of gill openings

Sturgeons (Acipenseridae)

- upper lobe of caudal fin longer than lower lobe

- two pairs of fleshy barbels before mouth under shovel-shaped snout

- large, bony plates on head, along back and side

Gars (Lepisosteidae)

- long, slender, cylindrical body with diamond-shaped, armour-like scales

- long, slender snout with needle-like teeth

- dorsal and anal fins far back on body

Bowfins (Amiidae)

- long, spineless dorsal fin

- rounded caudal fin

- large, bony plate underneath lower jaw

Freshwater eels (Anguillidae)

- long, thin body

- long dorsal fin joined to caudal and anal fins

- pectoral and pelvic fins present

- single pair of small gill openings

North American catfishes (Ictaluridae)

- four pairs of whisker-like barbels around mouth

- adipose fin

- scaleless body

- spines leading pectoral and dorsal fins

Pikes and pickerels (Esocidae)

- duckbill-like snout

- dorsal and anal fins far back on long, cylindrical body

- large teeth

Temperate basses (Moronidae)

- thin, deep body

- large spine on gill cover

- two distinct or slightly joined dorsal fins

- silvery body

Species accounts

- Species are grouped by evolutionary order of families, followed by groups of similar-looking species within families

- The following information is presented in the species accounts (modified from Holm et al. 2010):

- Characteristics: anatomical features used to distinguish species from similar species

- Size: Ontario average; Ontario record

- Similar species: other species with which the species may be confused

- Ontario distribution: general distribution in Ontario

- Habitat: brief description of habitat used by the species

- Use as bait: description of use as bait if it is a legal baitfish, or the reason for its prohibited or cautionary use

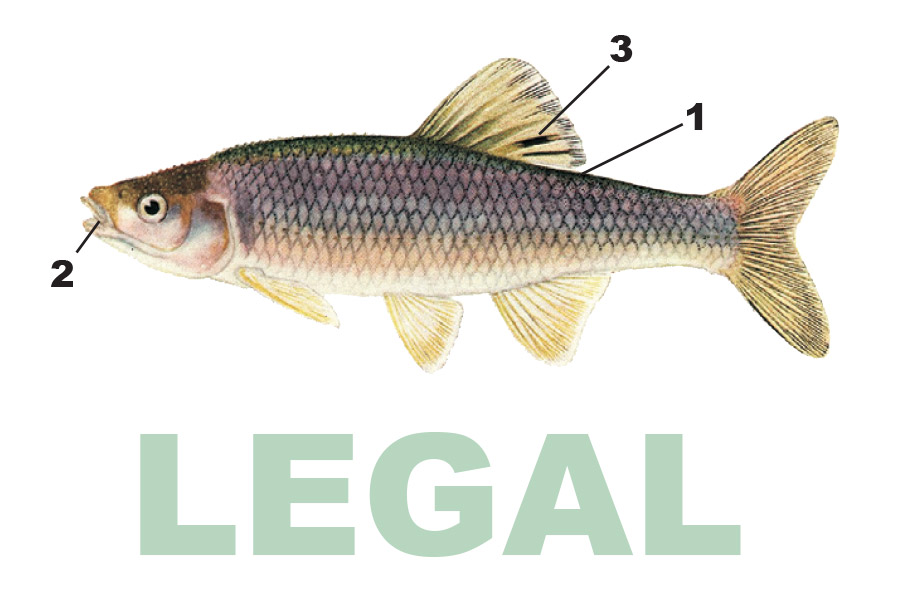

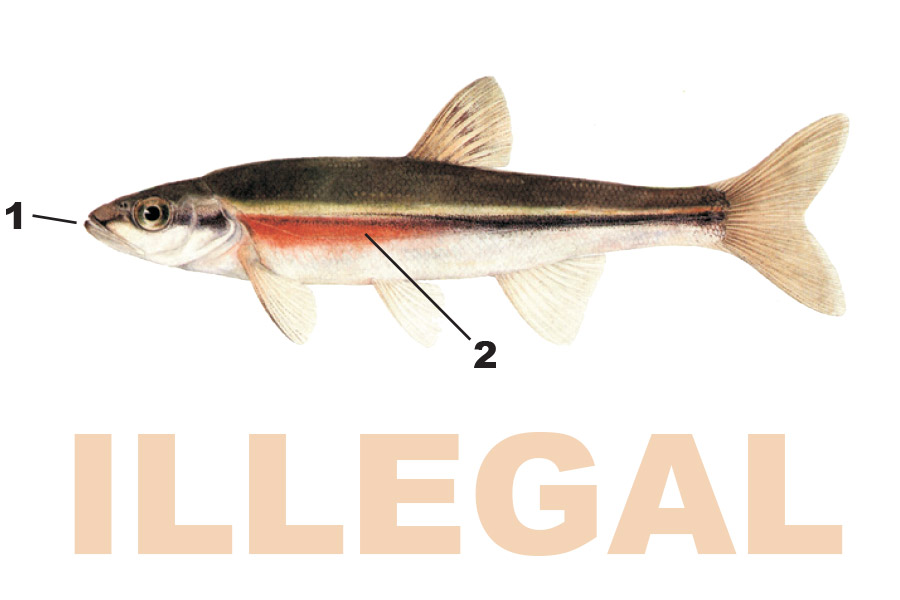

- The species are also labeled as Legal, Caution or Illegal based on the following criteria:

- Legal: listed as a species of baitfish in the Ontario Fishery Regulations, 2007 (OFRs) and not easily confused with illegal species.

- Caution: while not illegal, its use is considered cautionary, as it may be easily confused with illegal species.

- Illegal: the use of the species is prohibited as:

- it is listed as Extirpated, Endangered, Threatened, or of Special Concern under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) or the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)

- it is not listed as legal bait species under the OFRs; or

- it is listed as an invasive fish species in the under federal or provincial legislation and regulations

Herrings

Alewife

(Alosa pseudoharengus)

Characteristics:

- very laterally compressed body

- belly with saw-toothed edge

- large eye

- large mouth

Similar species: Gizzard Shad

Ontario distribution: introduced throughout the Great Lakes

Habitat: open water

Use as bait: introduced; illegal under the OFRs

Gizzard Shad

(Dorosoma cepedianum)

Characteristics:

- very deep and laterally compressed body

- saw-toothed keel along belly

- very long last ray on dorsal fin

Similar species: Alewife, juvenile Bighead and Silver Carp

Ontario distribution: Southern Ontario

Habitat: cool nearshore waters in the pelagic zone of the Great Lakes as well as turbid, vegetated tributaries

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Carps and minnows

Blackchin Shiner

(Notropis heterodon)

Characteristics:

- upturned mouth

- black pigment on snout and chin

- scales darkly outlined

- black stripe along side has zig-zag appearance

Similar species: Blacknose Shiner, Bridle Shiner, Pugnose Minnow, Pugnose Shiner

Ontario distribution: central and northern Ontario, limited in southern Ontario

Habitat: vegetated, nearshore areas of lakes and small rivers

Use as bait: occasionally sold mixed with other shiners; CAUTION: similar physical appearance with several at-risk fishes.

Blacknose Shiner

(Notropis heterolepis)

Characteristics:

- black stripe around snout, barely onto upper lip and not on chin

- black crescents within stripe along side

- scales darkly outlined except above dark stripe along silver side

Similar species: Blackchin Shiner, Bridle Shiner, Pugnose Minnow, Pugnose Shiner

Ontario distribution: central and northern Ontario, limited in southern Ontario

Habitat: cool, clear, weedy streams and shallow bays of lakes with sand or gravel bottom

Use as bait: sold mixed with other shiners; CAUTION: similar physical appearance with several at-risk fishes.

Bridle Shiner

(Notropis bifrenatus)

Characteristics:

- small, upturned mouth

- brown-black stripe along side and around snout

- scales darkly outlined

- usually black spot at base of caudal fin

Similar species: Blackchin Shiner, Blacknose Shiner, Pugnose Minnow, Pugnose Shiner

Ontario distribution: southeastern Ontario

Habitat: clear, still, shallow streams, ponds or lakes with submerged aquatic vegetation and bottom is mud, silt, or sand

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Special Concern under SARA and ESA

Pugnose Minnow

(Opsopoeodus emiliae)

Characteristics:

- small, strongly upturned mouth

- two very dark areas (front and rear) on dorsal fin in breeding males

Similar species: Blackchin Shiner, Blacknose Shiner, Bridle Shiner, Pugnose Shiner

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: slow moving waters of turbid small to large streams

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Threatened under SARA and ESA.

Pugnose Shiner

(Notropis anogenus)

Characteristics:

- very small, upturned mouth

- black pigment on chin, lower lip, side of upper lip

- scales darkly outlined

- dark stripe along side

Similar species: Blackchin Shiner, Blacknose Shiner, Bridle Shiner, Pugnose Minnow

Ontario distribution: isolated populations in southwestern Ontario and the St. Lawrence River

Habitat: clear, heavily vegetated lakes, and pools of vegetated streams and rivers with clean sand or mud bottoms

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Threatened under SARA and ESA.

Blacknose Dace

(Rhinichthys atratulus)

Characteristics:

- thin barbel in corner of mouth

- no groove separating snout from upper lip

- pointed snout slightly overhangs mouth

- stripe along side, through eye and onto snout

Similar species: Longnose Dace

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: small, cool, clear, fast streams with rocky or gravelly substrate

Use as bait: used to a limited extent in Ontario; considered a relatively hardy species

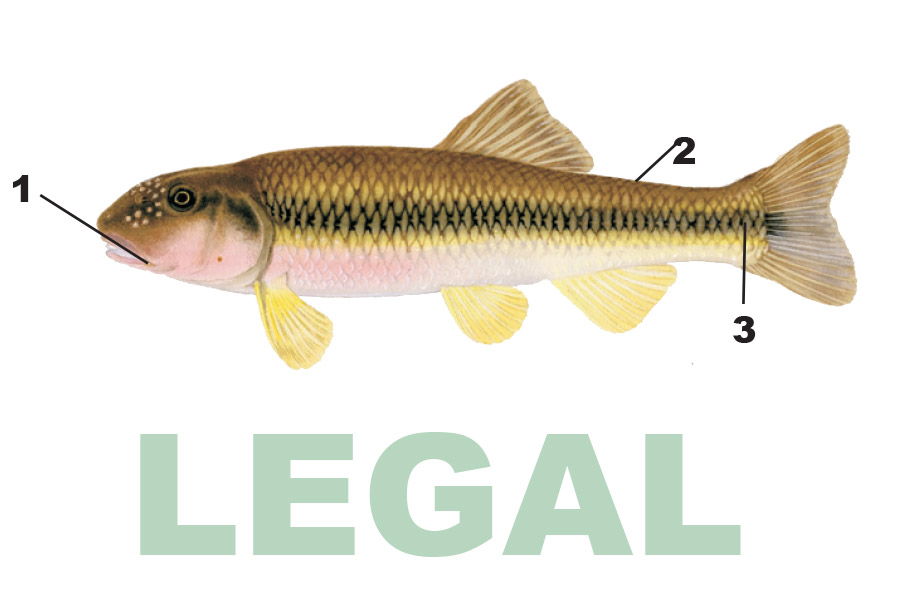

Longnose Dace

(Rhinichthys cataractae)

Characteristics:

- thin barbel in corner of mouth

- no groove separating snout from upper lip

- long, fleshy snout extends beyond mouth

Similar species: Blacknose Dace

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: clean, swift streams with gravel beds, occasionally taken in inshore waters of lakes

Use as bait: not commonly used, possibly because of its drab colouration and its intolerance of the still water of bait buckets

Bluntnose Minnow

(Pimephales notatus)

Characteristics:

- crowded scales between head and dorsal fin

- blunt snout overhanging small mouth

- scales darkly outlined (often with cross-hatched appearance)

- conspicuous black spot on caudal fin base

Similar species: Fathead Minnow

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: main river channels over substrate of silt, sand, gravel or rocks; avoids heavy vegetation

Use as bait: not a popular species as it does not withstand crowding in a bait bucket as well as other species

Fathead Minnow

(Pimephales promelas)

Characteristics:

- crowded scales between head and dorsal fin

- blunt snout with slanted mouth

- head short, flat on top

Similar species: Bluntnose Minnow

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: found in a wide range of habitats, but generally prefers still waters

Use as bait: angler preference varies locally; transports and holds well in commercial tanks and bait buckets

Brassy Minnow

(Hybognathus hankinsoni)

Characteristics:

- brassy-yellow body

- diffuse dusky stripe, developed on rear half of side

Similar species: Eastern Silvery Minnow

Ontario distribution: widespread in southern and northwestern Ontario

Habitat: small, sluggish weedy streams with sand, gravel or mud bottom covered by organic sediment; also common in silt-bottomed, shallow bog ponds, streams and lakes

Use as bait: not commonly used

Eastern Silvery Minnow

(Hybognathus regius)

Characteristics:

- small, slightly subterminal mouth, rounded snout

- body deepest and widest in front of dorsal fin

Similar species: Brassy Minnow

Ontario distribution: southeastern Ontario

Habitat: pools and backwaters of medium to large-sized streams with sandy bottoms

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Central Stoneroller

(Campostoma anomalum)

Characteristics:

- hard ridge along edge of lower jaw

- some speckling on sides

Similar species: none

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario, introduced in other parts of southern Ontario

Habitat: small- to medium-sized streams with moderate, sometimes fast current and gravel to rock bottoms with attached filamentous algae

Use as bait: occasionally used, becoming more common

Common Shiner

(Luxilus cornutus)

Characteristics:

- large scales, much deeper than wide

- dark stripe along middle of back

- crowded scales between head and dorsal fin

Similar species: Striped Shiner

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: small- to medium-sized weedless streams with gravel to rubble bottom, and nearshore of lakes

Use as bait: commonly used as a bait species - its large size and silvery appearance make it particularly attractive; transports and holds well in commercial tanks but does not live long in bait buckets

Striped Shiner

(Luxilus chrysocephalus)

Characteristics:

- large scales, much deeper than wide

- relatively deep body

- dark stripes on upper sides meet at middle of back behind dorsal fin to form large V's

- scales between head and dorsal fin not crowded

Similar species: Common Shiner

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: weedless, medium-sized streams with alternating pools and riffles over a gravel or rubble bottom, often with some silt

Use as bait: not known

Creek Chub

(Semotilus atromaculatus)

Characteristics:

- large black spot at front of dorsal fin base

- black caudal spot (not obvious in large individuals)

- black stripe along side around snout and onto upper lip

Similar species: Fallfish, Hornyhead Chub, Lake Chub, River Chub

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: small, clear, streams; nearshore of small lakes

Use as bait: one of the most important bait minnows as it is hardy, grows to a large size, and can be readily caught in most streams

Fallfish

(Semotilus corporalis)

Characteristics:

- small, thick barbel in groove above corner of mouth

- scales on back and upper side darkly outlined

Similar species: Creek Chub, Hornyhead Chub, Lake Chub, River Chub

Ontario distribution: eastern Ontario

Habitat: clear, flowing, gravel-bottomed streams, and lakes

Use as bait: limited use

Hornyhead Chub

(Nocomis biguttatus)

Characteristics:

- thin barbel at corner of large mouth

- large, dark-edged scales

- spot on base of tail

Similar species: Creek Chub, Fallfish, Lake Chub, River Chub

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario, introduced elsewhere

Habitat: small- to medium-sized clear streams with gravel bottoms

Use as bait: not important as a bait species in Ontario, probably due to limited distribution and may not be distinguished from the more common Creek Chub; highly regarded in the northern US, especially for Northern Pike; attains large size, is hardy, and can withstand handling in commercial storage tanks and bait buckets

River Chub

(Nocomis micropogon)

Characteristics:

- thin barbel at corner of large mouth

- large, dark-edged scales

- no spot on tail

Similar species: Creek Chub, Fallfish, Hornyhead Chub, Lake Chub

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario, introduced elsewhere

Habitat: medium-sized streams with gravel to boulder substrates

Use as bait: when used as a baitfish, it may not be distinguished from the more common Creek Chub

Lake Chub

(Couesius plumbeus)

Characteristics:

- thin barbel at corner of large mouth

- large pectoral fins

- lead-coloured sides and back

Similar species: Creek Chub, Fallfish, Hornyhead Chub, River Chub

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: gravel-bottomed pools and runs of streams, lakes

Use as bait: limited use as live bait in Lake Trout fishing in the vicinity of Rossport, Lake Superior; spring spawning runs fished by bait harvesters for Walleye bait

Cutlip Minnow

(Exoglossum maxillingua)

Characteristics:

- fleshy lobe on each side of lower jaw

Similar species: none

Ontario distribution: southeastern Ontario

Habitat: warm, clear, gravelly streams and rivers relatively free of vegetation and silt; dwells mostly under stones in quiet pools

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Special Concern under SARA and Threatened under ESA.

Emerald Shiner

(Notropis atherinoides)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- large mouth on fairly pointed snout

- dorsal fin origin behind pelvic fin origin

- black lips (front half)

Similar species: Rosyface Shiner, Silver Shiner

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: common in large rivers and lakes

Use as bait: very popular baitfish, particularly for ice fishing; most important commercial baitfish in Ontario; CAUTION: similar appearance to at-risk Silver Shiner

Rosyface Shiner

(Notropis rubellus)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- large mouth on sharply pointed long snouth

- dorsal fin origin well behind pelvic fin origin

- faint red at base of dorsal fin

Similar species: Emerald Shiner, Silver Shiner

Ontario distribution: southern Ontario

Habitat: clear, fast-flowing small- to medium-sized streams with bottoms of fine gravel or rubble, usually in or around riffles

Use as bait: not readily kept in commercial tanks

Silver Shiner

(Notropis photogenis)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- large mouth on long snout

- dorsal fin origin over pelvic fin

- two black crescents between nostrils

Similar species: Emerald Shiner, Rosyface Shiner

Ontario distribution: isolated populations in southern Ontario

Habitat: clear, weedless medium- to large-sized streams with clean gravel or boulder bottoms, usually in riffles and runs

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Threatened under SARA and ESA.

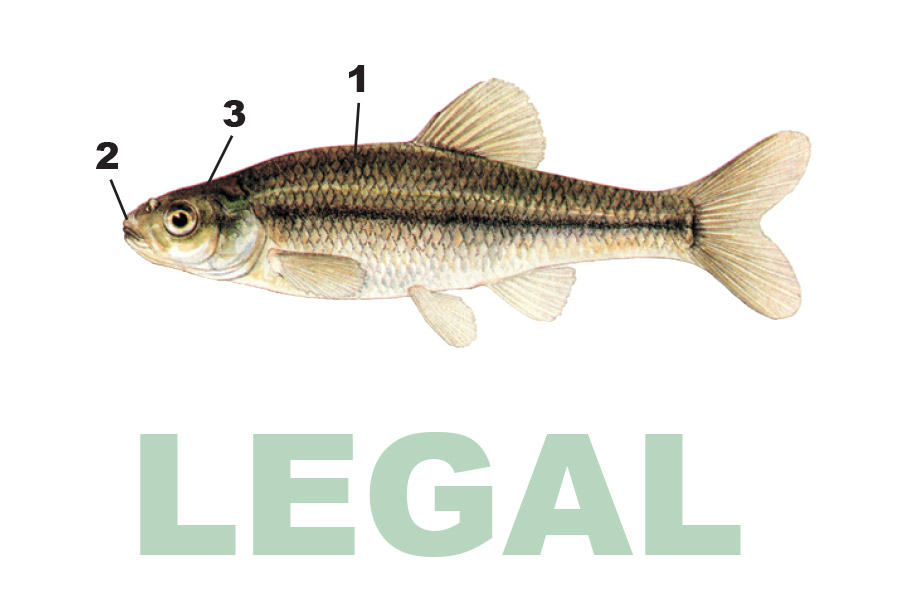

Finescale Dace

(Chrosomus neogaeus)

Characteristics:

- very small scales

- large mouth extending to under eye

- single black stripe along side

Similar species: Northern Redbelly Dace, Pearl Dace

Ontario distribution: central and northern Ontario, limited in southern Ontario

Habitat: tea-stained, cool, small, boggy streams and lakes usually over silt and near vegetation; often common in beaver ponds

Use as bait: widely distributed and often abundant baitfish

Northern Redbelly Dace

(Chrosomus eos)

Characteristics:

- very small scales

- small mouth

- two black stripes along side

Similar species: Finescale Dace, Pearl Dace

Ontario distribution: widespread in central and northern Ontario, limited in southern Ontario

Habitat: boggy streams, ponds and small lakes over a bottom of organic muck and vegetation

Use as bait: generally considered too small for a bait minnow but is hardy and readily available in less populated areas of Ontario, where it is used for bait

Northern Pearl Dace

(Margariscus nachtriebi)

Characteristics:

- very small scales

- small mouth

- barbel in groove above lip (often missing on one or both sides)

- many small black and brown specks on silver side

Similar species: Finescale Dace, Northern Redbelly Dace

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: boggy streams, ponds, and small lakes with sand or gravel bottoms

Use as bait: in many areas it is an important bait minnow, but is usually unrecognized and included with other species sold as chub or dace

Ghost Shiner

(Notropis buchanani)

Characteristics:

- body translucent milky white overall in colour

Similar species: Mimic Shiner, Sand Shiner, River Shiner

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: quiet waters of large streams and lakes with clean sand, gravel bottoms and some aquatic vegetation

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Mimic Shiner

(Notropis volucellus)

Characteristics:

- lateral band weakly pigmented

- black pigment surrounding anus

Similar species: Ghost Shiner, Sand Shiner, River Shiner

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: quiet or still waters of streams and lakes

Use as bait: common; usually captured incidentally while harvesting other baitfishes, such as Emerald Shiner; CAUTION: similar in appearance to illegal Ghost Shiner

River Shiner

(Notropis blennius)

Characteristics:

- Rounded snout overhangs mouth

- Uniform dark stripe along back

- Dorsal fin origin directly over pelvic fin origin

- Mostly silvery with small dark pigment on sides

Similar species: Ghost Shiner, Mimic Shiner, Sand Shiner

Ontario distribution: northwestern Ontario, Rainy River and Lake-of-the-Woods

Habitat: pools and main channels of medium to large rivers, low to moderate velocities, silt and gravel substrates

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Sand Shiner

(Notropis stramineus)

Characteristics:

- lateral band weakly pigmented

- no black pigment surrounding anus

Similar species: Ghost Shiner, Mimic Shiner, River Shiner

Ontario distribution: southern Ontario

Habitat: sandy shallows of small- to large-sized rivers and lakes with some rooted aquatic plants

Use as bait: transports and holds well in commercial tanks, can withstand low oxygen conditions; CAUTION: similar in appearance to illegal Ghost Shiner

Golden Shiner

(Notemigonus crysoleucas)

Characteristics:

- small, upturned mouth

- deep-bodied but very thin

- scaleless keel along belly from pelvic to anal fin

Similar species: Rudd

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: clear, weedy, quiet waters of streams and lakes

Use as bait: one of the most popular of all baitfishes in North America (including Ontario); easily damaged by handling; CAUTION: very similar in appearance to illegal Rudd

Rudd

(Scardinius erythrophthalmus)

Characteristics:

- small, upturned mouth

- deep-bodied but very thin

- scaled keel along belly from pelvic to anal fin

- bright red anal, pelvic and pectoral fins, red-brown dorsal and caudal fins

Similar species: Golden Shiner

Ontario distribution: isolated introduced populations in southern Ontario

Habitat: clear, weedy, quiet waters of streams and lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; invasive species

Redfin Shiner

(Lythrurus umbratilis)

Characteristics:

- very small scales in front of dorsal fin

- dark spot at dorsal fin origin

Similar species: Spotfin Shiner

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: quiet waters of creeks and small- to medium-sized rivers, with some vegetation

Use as bait: generally considered too small and uncommon in Ontario to be used as baitfish

Spotfin Shiner

(Cyprinella spiloptera)

Characteristics:

- scales on side diamond-shaped (taller than wide)

- dusky to black bar on chin

- black spot on rear half of dorsal fin

Similar species: Redfin Shiner

Ontario distribution: southern Ontario

Habitat: medium- to large-sized unvegetated streams over sand, gravel, or rubble, often in somewhat turbid waters

Use as bait: can be used as a baitfish but of no real importance in Ontario due to limited distribution; not readily kept in tanks

Silver Chub

(Macrhybopsis storeriana)

Characteristics:

- rounded snout overhanging mouth

- barbel in corner of mouth

- no spot on caudal peduncle

Similar species: Spottail Shiner

Ontario distribution: Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair

Habitat: shallow areas of Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Endangered under SARA and Threatened under ESA.

Spottail Shiner

(Notropis hudsonius)

Characteristics:

- rounded snout overhanging mouth

- no barbel

- large black caudal spot

Similar species: Silver Chub

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: large streams and lakes, usually over sandy or rocky shallows with sparse vegetation

Use as bait: most frequently used bait minnow in many parts of northern and eastern Ontario

Common Carp

(Cyprinus carpio)

Characteristics:

- large scales

- deep, thick body, strongly arched to dorsal fin, flattened behind

- saw-toothed spine at front of dorsal, pectoral and anal fins

- two barbels on each side of upper jaw

Similar species: Goldfish, Grass Carp, Tench

Ontario distribution: introduced throughout southern Ontario, isolated populations in northern Ontario

Habitat: wide variety of habitats, in small- to large-sized streams, nearshore of lakes over all types of substrates

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; introduced

Goldfish

(Carassius auratus)

Characteristics:

- Large scales

- deep, thick body, strongly arched to dorsal fin

- saw-toothed spine at front of dorsal, pectoral and anal fins

- no barbels

Similar species: Common Carp, Tench

Ontario distribution: introduced throughout southwestern Ontario, isolated populations elsewhere.

Habitat: wide variety of habitats, in small to large streams, nearshore of lakes over all types of substrates

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; introduced

Tench

(Tinca tinca)

Characteristics:

- very small scales

- one barbel on each side of upper jaw

Similar species: Common Carp, Goldfish, Lake Chubsucker

Ontario distribution: potential invader

Habitat: shallow, muddy vegetated ponds, lakes, and streams

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Bighead Carp

(Hypophthalmichthys nobilis)

Characteristics:

- eye sits below the mouth

- small scales with dark blotches

- no barbels

- no long last ray on dorsal fin

Similar species: Silver Carp, Gizzard Shad

Ontario distribution: potential invader

Habitat: wide variety of habitats in large streams and lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs, ISA, and federal AIS regulations

Black Carp

(Mylopharyngodon piceus)

Characteristics:

- large scales

- thick body, not deep

- large, dark-edged scales

- no spines on dorsal, pectoral and anal fins

- no barbels

Similar species: Grass Carp, Goldfish, Tench

Ontario distribution: potential invader

Habitat: wide variety of habitats in large streams and lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs, ISA, and federal AIS regulations

Grass Carp

(Ctenopharyngodon idella)

Characteristics:

- large scales

- thick body, not deep

- large, dark-edged scales

- no spines on dorsal, pectoral and anal fins

- no barbels

Similar species: Black Carp, Common Carp, Goldfish, Tench, Fallfish

Ontario distribution: isolated individuals introduced in southern Ontario

Habitat: wide variety of habitats, large streams and nearshore of lakes, typically with aquatic vegetation

Use as bait: invasive; illegal under the OFRs, ISA, and federal AIS regulations

Silver Carp

(Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)

Characteristics:

- eye sits below the mouth

- small, shiny scales

- no barbels

- no long last ray on dorsal fin

Similar species: Bighead Carp, Gizzard Shad

Ontario distribution: potential invader

Habitat: wide variety of habitats in large streams and lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs, ISA, and federal AIS regulations

Gravel Chub

(Erimystax x-punctatus)

Characteristics:

- small, thin barbel in corner of mouth

- many dark X's on back and side

Similar species: Creek Chub, Fallfish, Hornyhead Chub, Lake Chub, River Chub

Ontario distribution: only known from the Thames River in the 1950's

Habitat: gravel-bottomed small- to large-sized streams, preferably slow moving and deep

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Extirpated under SARA and ESA.

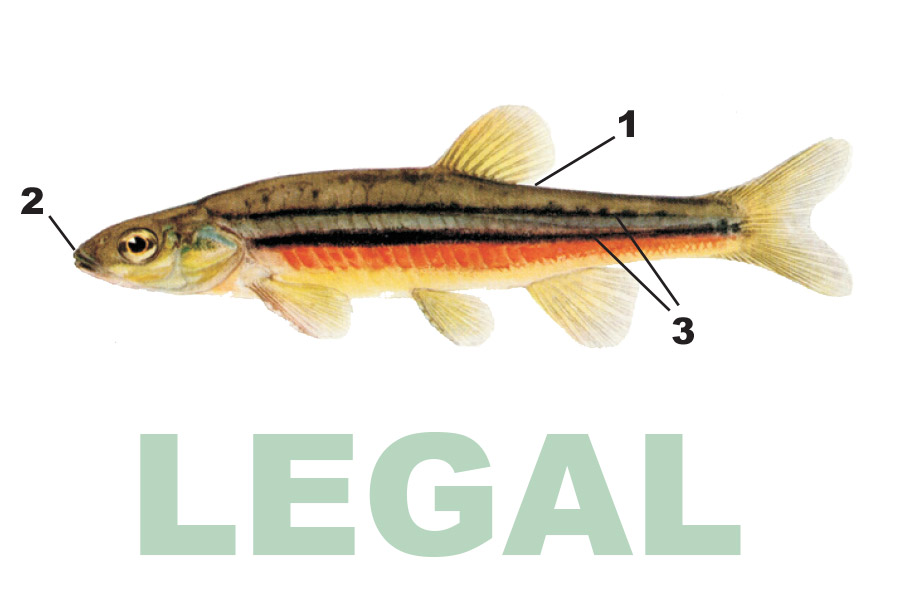

Redside Dace

(Clinostomus elongatus)

Characteristics:

- long pointed snout, with very large mouth

- bright red stripe on lower side

Similar species: Finescale Dace, Northern Redbelly Dace, Pearl Dace

Ontario distribution: Isolated populations throughout southern Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie

Habitat: clear, cool, flowing streams over rubble or gravel substrate

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Endangered under ESA and SARA.

Suckers and redhorses

Longnose Sucker

(Catostomus catostomus)

Characteristics:

- thick lips with many ‘pimples'

- very small scales

Similar species: Northern Hog Sucker, White Sucker

Ontario distribution: Great Lakes, central and northern Ontario

Habitat: cold, deep lakes

Use as bait: only incidental, caught rarely with small White Suckers

Northern Hog Sucker

(Hypentelium nigricans)

Characteristics:

- thick lips with ‘pimples'

- large scales

- large, rectangular head, broadly flat (young) or concave (adult) between eyes

- three to six dusky-brown saddles on upper side

Similar species: Longnose Sucker, White Sucker

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: riffles and adjacent pools of clear shallow streams with gravel to rubble substrates; found infrequently in shallow lakes near the mouths of streams

Use as bait: limited, sometimes sold as “pike” bait

White Sucker

(Catostomus commersonii)

Characteristics:

- thick lips (lower lip about twice as thick as upper lip) with many “pimples”

- small scales

Similar species: Longnose Sucker, Northern Hog Sucker

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: found in a wide range of habitats

Use as bait: widespread; often sold as “pike” bait

Lake Chubsucker

(Erimyzon sucetta)

Characteristics:

- thin lips with grooves on small, slightly upturned mouth

- deep body

- rounded edge on dorsal fin

- no barbels

Similar species: other suckers; Tench

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: shallow, clear, vegetated ponds and lakes over silt, sand or debris; rarely in streams

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Threatened under ESA and Endangered under SARA

Black Redhorse

(Moxostoma duquesnei)

Characteristics:

- mouth under snout has thick lips with grooves

- large scales

- gray caudal fin

- concave dorsal fin

- lower lip not notched

Similar species: Golden Redhorse, Greater Redhorse, River Redhorse, Shorthead Redhorse, Silver Redhorse, White Sucker

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: pools in the swifter flowing medium-to-large rivers

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Threatened under SARA and ESA.

Golden Redhorse

(Moxostoma erythrurum)

Characteristics:

- large scales

- gray caudal fin

- concave dorsal fin

- lower lip notched

Similar species: Black Redhorse, Greater Redhorse, River Redhorse, Shorthead Redhorse, Silver Redhorse, White Sucker

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: clear, small- to large-sized streams in riffles over variety of substrates

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Greater Redhorse

(Moxostoma valenciennesi)

Characteristics:

- thick lips with grooves

- large scales

- red caudal fin

- concave dorsal fin

- grooves on lower lip are parallel

Similar species: Black Redhorse, Golden Redhorse, River Redhorse, Shorthead Redhorse, Silver Redhorse, White Sucker

Ontario distribution: southern Ontario

Habitat: large streams in riffles with bottoms of clean sand, gravel or boulders

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

River Redhorse

(Moxostoma carinatum)

Characteristics:

- mouth under snout has thick lips with grooves

- large scales

- red caudal fin

- dorsal fin edge usually straight

- grooves on lower lip are parallel

Similar species: isolated populations in southern Ontario

Ontario distribution: Black, Golden, Greater, Shorthead, and Silver Redhorses; White Sucker

Habitat: rocky pools and swift runs of small-to-large sized streams ; impoundments

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Special Concern under SARA and ESA.

Shorthead Redhorse

(Moxostoma macrolepidotum)

Characteristics:

- thick lips with grooves

- large scales

- red caudal fin

- concave dorsal fin

- lower lip notched

Similar species: Black, Golden, Greater, River, and Silver Redhorses; White Sucker

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: lakes and streams over bottoms of sand or gravel without heavy silt

Use as bait: CAUTION: redhorse species (including species at risk) are very difficult to distinguish from one another

Silver Redhorse

(Moxostoma anisurum)

Characteristics:

- thick lips with grooves or pimples on mouth under snout

- large scales

- gray caudal fin

- convex dorsal fin

- lower lip notched

Similar species: Black, Golden, Greater, River, and Shorthead Redhorses; White Sucker

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: mud- to rock bottomed pools and runs of small- to large-sized streams; occasionally lakes

Use as bait: CAUTION: redhorse species (including species at risk) are very difficult to distinguish from one another

Spotted Sucker

(Minytrema melanops)

Characteristics:

- thin lips with grooves

- small scales

- rows of dark spots at scale bases on back and side

Similar species: other suckers

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: creeks and small rivers with sandy, gravelly, or hard clay bottoms without silt, but occasionally in large rivers and impoundments

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Special Concern under SARA and ESA.

Mudminnows

Central Mudminnow

(Umbra limi)

Characteristics:

- dorsal and anal fins far back on body

- black bar on caudal fin base

- rounded caudal fin

Similar species: Blackstripe Topminnow; Banded Killifish

Ontario distribution: southern Ontario

Habitat: still, mud-bottomed, often heavily vegetated streams and ponds

Use as bait: sold and used as bait, hardy (capable of breathing air)

Smelts

Rainbow Smelt

(Osmerus mordax)

Characteristics:

- streamlined, elongate body

- adipose fin

- large teeth on jaw and tongue

Similar species: Cisco species (illegal baitfish, most at risk; most not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: native to Ottawa Valley in Ontario, widely introduced elsewhere

Habitat: open waters of lakes

Use as bait: introduced; illegal under the OFRs

Salmon, trouts and whitefishes

Cisco

(Coregonus artedi)

Characteristics:

- streamlined, elongate body

- adipose fin

- no teeth

Similar species: Rainbow Smelt; other Cisco species (illegal baitfishes, most at risk; not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: Great Lakes, central and northern Ontario

Habitat: primarily found in opens waters of lakes but may occur in large streams

Use as bait: popular in some areas for use as bait for Lake Trout and salmon; CAUTION: similar in appearance to illegal Rainbow Smelt and other at-risk cisco species

New world silversides

Brookside Silverside

(Labidesthes sicculus)

Characteristics:

- small upturned mouth

- two dorsal fins

- long anal fin

Similar species: Emerald Shiner, Rainbow Smelt, Silver Shiner

Ontario distribution: southern Ontario

Habitat: warm surface waters of clear streams and nearshores of lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Topminnows

Banded Killifish

(Fundulus diaphanus)

Characteristics:

- small upturned mouth

- 12-20 vertical bars

Similar species: Blackstripe Topminnow; Central Mudminnow

Ontario distribution: southern and northwestern Ontario

Habitat: warm surface waters of clear streams and nearshores of lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs

Blackstripe Topminnow

(Fundulus notatus)

Characteristics:

- small upturned mouth

- dark lateral stripe along side

Similar species: Banded Killifish; Central Mudminnow

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: warm surface waters of small streams

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Special Concern under SARA and ESA.

Trout-perches

Trout-Perch

(Percopsis omiscomaycus)

Characteristics:

- large, unscaled head

- adipose fin

- spines in dorsal, anal and pelvic fins

- rows of 7-12 dusky spots along back, upper side and side

Similar species: none

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: lakes or deep flowing pools of small- to large-sized streams, usually over sand

Use as bait: incidental capture and sold with mixed species

Sticklebacks

Brook Stickleback

(Culaea inconstans)

Characteristics:

- 4-7 (usually 5) short dorsal spines

- deep, thin body with no bony plates on side

Similar species: Fourspine, Ninespine and Threespine sticklebacks

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: quiet, vegetated waters of small rivers, ponds or lakes over sand, muck or mud

Use as bait: only incidental; CAUTION: similar in appearance to illegal Fourspine Stickleback

Fourspine Stickleback

(Apeltes quadracus)

Characteristics:

- four dorsal spines of various lengths, wide gap before last spine

- no bony plates on side

Similar species: Brook, Ninespine, and Threespine sticklebacks

Ontario distribution: introduced into northwestern Lake Superior

Habitat: quiet, vegetated waters

Use as bait: introduced; illegal under the OFRs

Ninespine Stickleback

(Pungitius pungitius)

Characteristics:

- nine short dorsal spines

- slender body

- well-developed keel on caudal peduncle

- no bony plates on side

Similar species: Brook, Fourspine, and Threespine sticklebacks

Ontario distribution: widespread in northern Ontario, the Great Lakes

Habitat: shallow, vegetated areas of streams, ponds or lakes; deep waters of Great Lakes

Use as bait: only incidental

Threespine Stickleback

(Gasterosteus aculeatus)

Characteristics:

- three dorsal spines, last very short

- bony plates on side

- bony keel along side of caudal peduncle

Similar species: Brook, Fourspine, and Ninespine sticklebacks

Ontario distribution: isolated populations mainly in central and eastern Ontario

Habitat: shallow areas over mud or sand with vegetation

Use as bait: incidental; CAUTION: has been introduced in some parts of Ontario

Sculpins

Mottled Sculpin

(Cottus bairdii)

Characteristics:

- dorsal fins joined at base

- 2-3 dark bars on body under second dorsal fin

- large black spots at front and rear of first dorsal fin

Similar species: Slimy Sculpin, Round Goby and Tubenose Goby (Spoonhead and Deepwater sculpins look similar but, due to their deepwater habitats, they are not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: riffles of small streams and headwaters over rubble or gravel; rocky shores of lakes

Use as bait: limited; CAUTION: easily confused with illegal gobies

Slimy Sculpin

(Cottus cognatus)

Characteristics:

- long, fairly slender body

- three pelvic rays

- prickles on head and behind pectoral fin base

Similar species: Mottled Sculpin, Round Goby and Tubenose Goby (Spoonhead and Deepwater sculpins look similar but, due to their deepwater habitats, they are not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: rocky areas of cold streams and lakes

Use as bait: limited; CAUTION: easily confused with illegal gobies

Perches and darters

Blackside Darter

(Percina maculata)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- large mouth

- 6-9 large oval black blotches along side

- black caudal spot

Similar species: Logperch

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: riffles and pools of medium-sized streams over gravel and sand with an abundance of vegetation

Use as bait: only incidental

Channel Darter

(Percina copelandi)

Characteristics:

- slender, elgonated body

- blunt snout

- 9-10 horizontally oblong black blotches along side

- black X's and W's on back and upper side

Similar species: River Darter

Ontario distribution: isolated populations in southwestern and southeastern Ontario

Habitat: pools and margins of riffles of small- to medium-sized streams usually over sand and gravel; shores of lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Special Concern under ESA. Lake Ontario and Lake Erie populations are listed as Endangered under SARA. St. Lawrence populations are listed as Special Concern under SARA.

Logperch

(Percina caprodes)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- large mouth

- dusky tear drop

- many alternating long and short bars along side

Similar species: Blackside Darter

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: medium to large streams, rivers and lakes over sand and gravel bottoms

Use as bait: occasionally used as live bait but cannot be held long in a bait bucket

River Darter

(Percina shumardi)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- large mouth

- black teardrop

- 8-15 black bars along side

- small black spot at front, large black spot near rear of first dorsal fin

Similar species: Channel Darter

Ontario distribution: widespread in northwestern Ontario, isolated populations in southwestern Ontario

Habitat: medium- to large-sized streams with strong, deep current over sand, gravel or rock

Use as bait: illegal for Great Lakes-Upper St. Lawrence populations as these are listed as Endangered under ESA. COSEWIC has assessed these populations as Endangered but status is pending under SARA. May only be used as bait in northwestern Ontario.

Fantail Darter

(Etheostoma flabellare)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- small mouth

- black bands on second dorsal fin and caudal fin

- gold knobs on tips of dorsal spines

Similar species: Greenside Darter, Iowa Darter, Johnny Darter, Least Darter, Rainbow Darter, Tessellated Darter

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: gravel- and boulder-bottomed streams of slow to moderate flow

Use as bait: only incidental

Greenside Darter

(Etheostoma blennioides)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- small mouth

- dusky teardrop

- 5-18 green W's, V's, or bars on side

Similar species: Fantail Darter, Iowa Darter, Johnny Darter, Least Darter, Rainbow Darter, Tessellated Darter

Ontario distribution: isolated populations in southwestern Ontario

Habitat: small- to large-sized streams among rubble and small boulders with attached filamentous algae

Use as bait: illegal under OFRs; introduced beyond native range

Iowa Darter

(Etheostoma exile)

Characteristics:

- slender, elgonated body

- small mouth

- black teardrop

- middle red band on first dorsal fin

Similar species: Fantail Darter, Greenside Darter, Johnny Darter, Least Darter, Rainbow Darter, Tessellated Darter

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: clear, standing, or slowly moving waters of streams, small to medium rivers and lakes with aquatic vegetation, and a bottom of organic debris and sand

Use as bait: only incidental

Johnny Darter

(Etheostoma nigrum)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- small mouth

- black teardrop

- dark brown X's and W's along side

Similar species: Fantail Darter, Greenside Darter, Iowa Darter, Least Darter, Rainbow Darter, Tessellated Darter

Ontario distribution: widespread

Habitat: wide variety of aquatic habitats but most common in quieter waters over bottom of sand, gravel, silt, or a combination of these, but do inhabit weedy areas or gravel riffles of streams

Use as bait: only incidental

Least Darter

(Etheostoma microperca)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- small mouth

- large, black teardrop

- dark green saddles

Similar species: Fantail Darter, Greenside Darter, Iowa Darter, Johnny Darter, Rainbow Darter, Tessellated Darter

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario, isolated populations in northern Ontario

Habitat: clear, quiet, weedy waters of lakes and slow-moving small- to medium-sized streams

Use as bait: likely none as a result of small size

Rainbow Darter

(Etheostoma caeruleum)

Characteristics:

- relatively deep-bodied

- small mouth

- no teardrop

- 6-10 dark saddles

Similar species: Fantail Darter, Greenside Darter, Iowa Darter, Johnny Darter, Least Darter, Tessellated Darter

Ontario distribution: southwestern Ontario

Habitat: fast-flowing gravel and rubble-bottomed riffles of small to medium streams

Use as bait: only incidental

Tesselated Darter

(Etheostoma olmstedi)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate body

- small mouth

- black teardrop

- dark brown X's and W's along side

- six dark brown saddles

Similar species: Fantail Darter, Greenside Darter, Iowa Darter, Johnny Darter, Least Darter, Rainbow Darter

Ontario distribution: southeastern Ontario

Habitat: lakes and rivers over mud, sand or rock bottom

Use as bait: only incidental

Eastern Sand Darter

(Ammocrypta pellucida)

Characteristics:

- slender, elongate, transparent body

- 10-19 horizontal dark green blotches along side

Similar species: other darters

Ontario distribution: isolated populations in southwestern and southeastern Ontario

Habitat: sand-bottomed areas of small to large streams and wave-protected beaches of large lakes

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; listed as Threatened under SARA and Endangered under ESA.

Ruffe

(Gymnocephalus cernua)

Characteristics:

- fairly deep, compressed body

- broadly joined, spiny dorsal fins

- many small black spots on dorsal and caudal fins

Similar species: Yellow Perch (not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: introduced into western Lake Superior

Habitat: lakes; quiet pools and margins of streams

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; invasive species

Gobies

Tubenose Goby

(Proterorhinus semilunaris)

Characteristics:

- fused pelvic fins

- long anterior nostrils

- spiny dorsal fin with oblique black lines (no spot)

Similar species: Round Goby, Mottled and Slimy Sculpins (Spoonhead and Deepwater sculpins - not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: isolated, introduced populations in southwestern Ontario and Lake Superior basin

Habitat: shallow, vegetated areas of lakes and streams

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; invasive species

Round Goby

(Neogobius melanostomus)

Characteristics:

- fused pelvic fins

- greenish, spiny dorsal fin with a black spot

Similar species: Tubenose Goby, Mottled and Slimy sculpins (Spoonhead and Deepwater sculpins - not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: introduced populations in the Great Lakes and tributaries

Habitat: rocky or gravelly habitat, generally inhabit the nearshore area of lakes but will migrate to deeper water in winter; also found in tributaries

Use as bait: illegal under the OFRs; invasive species

Crayfishes

Rusty Crayfish

(Orconectes rusticus)

Characteristics:

- greenish coloured claws with dark black bands near the tips

- prominent rusty patches on either side of the carapace

Similar species: native crayfishes (not included in this Primer)

Ontario distribution: isolated, introduced in southern Ontario

Habitat: streams and lakes with adequate rock, log, and debris cover and substrates of clay, silt and gravel

Use as bait: CAUTION: overland transport is prohibited; crayfishes in general cannot be commercially harvested or sold; anglers can capture their own bait but must use it in the waterbody where it is captured

What you can do to minimize impacts to aquatic ecosystems

- Follow the latest version of the Ontario Fishery Regulations Summary (2017) as it pertains to the harvest, sale, and use of baitfishes.

- Do not release any live bait or dump the contents of a bait bucket, including the water, into any waters or within 30 m of any waters - it is illegal.

- Be cautious in timing of baitfish harvesting. 95% of legal baitfishes in this Primer are known to spawn in Ontario during the spring months (April-June).

- Do not over-harvest one area.

- Use traps instead of nets (note only licensed harvesters can use seine nets), especially in vegetated areas. Resident anglers must only use traps or dipnets.

- Remember, not all small fishes are “minnows”. “Minnows” refers to a specific family of fishes, the Carps and Minnows family (Cyprinidae). All fish species, including sportfishes, are small at some time during their lives.

- Never release species into a waterbody from which they were not harvested.

- If you suspect a species at risk has been harvested, return it immediately to the place of capture.

- Avoid transfer of introduced species - destroy all unused bait at least 30 m from a waterbody.

- Report sightings or capture of introduced species to the Invading Species Hotline at 1-800-563-7711 or visit www.invadingspecies.com. The Hotline is operated by the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Any invasive species caught should be immediately destroyed and not released back into any waters.

- To report a natural resources violation, please call 1-877-TIPS-MNR (847-7667) toll-free anytime. You can also call Crime Stoppers anonymously at 1-800-222-TIPS (8477).

Further reading

- Boschung, H. T., J.D. Williams, D.W. Gotshall, D.K. Caldwell and M.C. Caldwell. 1989. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Fishes, Whales, and Dolphins. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY

- Coad, B.W. 1995. Encyclopedia of Canadian Fishes. Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, ON and Canadian Sportfishing Productions Inc., Burlington, ON

- Holm, E., N. E. Mandrak and M. E. Burridge. 2010. The ROM Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Ontario. Royal Ontario Museum. 468 pp

- Lavett-Smith, C. 1994. Fish Watching: An Outdoor Guide to Freshwater Fishes. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca, NY

- Lui, K., B. Butler, M. Allen, J. da Silva and B. Brownson. 2008. Field Guide to Aquatic Invasive Species. Queens Printer for Ontario. www.invadingspecies.com

- Moyle, P.B. 1993. Fish: An Enthusiast's Guide. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Page, L.M. and B.M. Burr. 2011. A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes: North America North of Mexico. Peterson Field Guides. Houghton Mifflin Co., New York, NY

- Scott, W.B. and E.J. Crossman. 1973. Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 184. (1999 Reprint, Galt House Publications, Oakville, ON)

- DFO Publications: Projects Near Water, Measures to Avoid and Mitigate Harm, Information about Fish Species and Habitats and other DFO publications – www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca. Follow the links to Publications under “About Us”, Projects Near Water under “Ecosystems” and Fish Species Details under “Species”

- Bait Association of Ontario and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2005. The Comprehensive Bait Guide for Eastern Canada, the Great Lakes Region and Northeastern United States. University of Toronto Press. 437 pp

- Bait Association of Ontario and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2005. The Essential Bait Guide for Eastern Canada, the Great Lakes Region and Northeastern United States. University of Toronto Press. 193 pp

Contacts

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

867 Lakeshore Road

Burlington, Ontario L7S 1A1

Toll-Free 855-852-8320

dfo-mpo.gc.ca

Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters

4601 Guthrie Drive, PO Box 2800

Peterborough, ON K9J 8L5

705-748-6324 Fax: 705-748-9577

www.ofah.org

Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Robinson Pl South Tower 4th Flr S

300 Water Street

Peterborough ON K9J 8M5

1-800-667-1940; Fax 705-755-3233

mnr.gov.on.ca or contact your local office

- Date modified: