Shark anatomy

Although a few species of sharks venture into fresh water on occasion, all sharks are marine fishes. They are an easily recognizable group of fish to most people, although their closest evolutionary relatives are the very different looking skates and rays.

To take a look at various aspects of shark anatomy click on selections below.

Fins

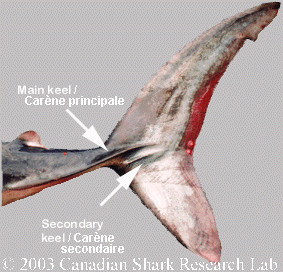

The fins of sharks are used for stabilizing, steering, lift and propulsion. Each of the fins are used in a different manner. There are one or two fins present along the dorsal midline called the first and second dorsal fin. These are anti-roll stabilizing fins. These two fins may, or may not have spines at their origin. When spines are present they are defensive, and may also have skin glands associated with them that produce an irritating substance. Pectoral fins originate behind the head and extend outwards. These fins are used for steering during swimming and help to provide the shark with lift. Pelvic fins are found near the claoca and are also stabilizers. In males they have a secondary function as they are modified into copulatory organs called claspers. Anal fins may be absent, but if present they are located between the pelvic and caudal fins. The tail region itself consists of the caudal peduncle and the caudal fin. The caudal peduncle may have notches known as precaudal pits found just ahead of the caudal fin. The peduncle may also be horizontally flattened into lateral keels. The caudal fin has both an upper and lower lobe that can be of different sizes and the shape varies across species.The primary use of the caudal fin (hetereocercal or homocercal) is to provide thrust. The upper lobe of the caudal fin produces the most thrust, and at least some of that would tend to force the shark downwards. Lift to counter this force is provided by the pectoral fins and the shape of the body (like an airfoil) working together. The strong non-lunate caudal fin (heterocercal) in most benthic shark species allows for unhampered swimming close to the seabed (i.e. nurse sharks and zebra sharks). However, The fastest swimming sharks (such as makos and porbeagles) tend to have lunate shaped caudal fins (homocercal) consistant with the requirement for maximum thrust.

Shark Skeleton

Like other fish, sharks possess an internal skeleton. A sharks skeleton differs from that of other fish because it is composed entirely of cartilage. Cartilage is a strong and durable material but also light weight and relatively flexible. These characteristics aid in the general movements of the shark in a variety of ways. For example, cartilage is lighter than bone and helps keep the shark from sinking (since a shark has no swim bladder for buoyancy like other fish) and allows the shark to turn in a tighter radius than other fish. Cartilage found in the jaws and backbones of sharks require more strength then the cartilage found in the fins. These areas are strengthened with calcium salts forming a "calcified cartilage" which has similar strength characteristics of bone without the added weight.

Like the rest of its skeleton, the skull of a shark is made mostly of cartilage. The shape of the skull can be variable, ranging from the classic shape of a porbeagle skull, as seen below, to the broad and flat shape of a hammerhead shark. This picture of the head of a porbeagle shark has a photograph of the skull superimposed on top of it. The cartilage in the rostrum is spongy and flexible, allowing the shark to absorb considerable impact with its nose.

The most variable aspect of a shark skull is the jaw. The jaw can be attached to the cranium in different ways and this is generally related to the method in which the animal feeds. The most common type of jaw found in modern sharks allows the full jaw to swing down and forward in order to swallow larger prey items.

Shark Eyes

Sharks posses the basic eye structure that is found in all vertebrates, but with some modification. The shark eye has a reflecting layer called a tapetum lucidum located behind the retina. Essentially the structure consists of a layer of parallel, plate-like cells filled with silver guanine crystals. The crystals reflect light that has already passed through the retina and redirects it back to restimulate the retina as it passes out through the eye. This effectively boosts the visual signal, especially in low light levels giving sharks high visual acuity.

Another modification found in some sharks is the presence of a nictitating membrane. This structure is a denticle covered membrane that protects the eye. It closes when the shark passes close to a objects and also during biting or feeding.

Gills

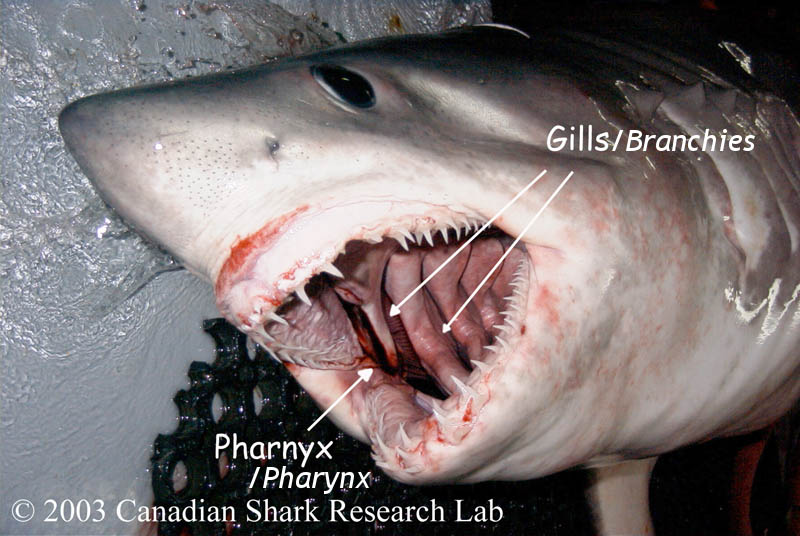

All sharks have five to seven pairs of gills on the side of the head. Gas exchange occurs at the gills and oxygenated water must always be flowing over the gill filaments for respiration to occur. Water enters through the mouth of the animal, into the pharynx, over the gills and exits through the gill slits. Respiratory gas exchange takes place on the surface of the gill filaments as the water passes over and out the gills.

Spiracle

The spiracle is a vestigial first gill slit. It appears as an opening behind the eye, as in the spiny dogfish photo below. It is absent or reduced in many sharks, especially the fast swimming sharks and is usually larger and present in sedentary or bottom dwelling sharks. The spiracle in sharks is used to provide oxygenated blood directly to the eye and brain through a separate blood vessel. In the rays, the spiracle is much larger and more developed and is used to actively pump water over the gills to allow the ray to breathe while buried in the sand.

Teeth

Shark teeth are not lodged permanently within the jaw, but are attached to a membrane known as a tooth bed. The tooth bed membrane is similar to a conveyor belt, moving the rows of teeth forward as the shark grows, thus replacing the older teeth in front that have become damaged, fallen out or worn down. It is not uncommon for shark teeth to be found lodged in large prey (such as whale carcasses) or loose on the ocean floor.

The shape, number and appearance of shark teeth varies considerably among shark species, and can be one of the most important features for species identification. However, tooth appearance can also differ between the upper and lower jaw, and from front to back, within any given shark.

The blue shark is a good example of how teeth can differ between the upper and lower jaws. The upper teeth (left) are triangular and curved with serrated edges and overlapping bases. The lower teeth (right) are more straight and slender with finely serrated edges.

The teeth of the porbeagle and mako are alike in both the upper and lower jaws. The porbeagle (left) has smooth edged teeth with lateral denticles while the mako (right) has more slender teeth without lateral denticles.

Ampullae of Lorenzini

The ampullae of Lorenzini are small vesicles and pores that form part of an extensive subcutaneous sensory network system. These vesicles and pores are found around the head of the shark and are visible to the naked eye. They appear as dark spots in the photo of a porbeagle shark head below. The ampullae detect weak magnetic fields produced by other fishes, at least over short ranges. This enables the shark to locate prey that are buried in the sand, or orient to nearby movement.

Recent research suggests that the ampullae may also allow the shark to detect changes in water temperature. Each ampulla is a bundle of sensory cells that are enervated by several nerve fibers. These fibers are enclosed in a gel-filled tubule which has a direct opening to the surface through a pore. The gel (a glyco-protein based substance) has electrical properties similar to a semiconductor, allowing temperature changes to be translated into electrical information that the shark can use to help detect temperature gradients.

Lateral Line

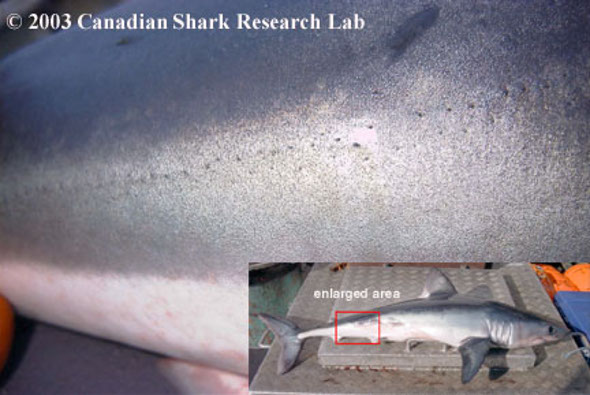

Figure 1 : The tiny pores of the lateral line system of a porbeagle shark run the length of the body from head to tail.

The lateral line, together with the ampullae of Lorenzini comprise the electrosensory component of the sharks sensory system. The lateral line allows the shark to orient to particle movement or sound. It consists of structures called neuromasts which are located in canals that lie just below the surface of the skin or the scales. Similar to the ampullae of Lorenzini there are pores that open to the outside and movement caused by prey can be detcted by the neuromasts.

Skin

Shark skin feels like sandpaper because it has small rough placoid scales (also known as dermal denticles). As a result, it is often dried and used as a leather product or sandpaper. Placoid scales consist of a basal bony plate buried within the skin and a raised portion that is exposed. Dermal denticles are homologous in structure to teeth, and are what gives the skin a rough feeling.

Dermal denticles, as seen in this image taken from the dorsal fin of a porbeagle shark, are small tooth-like structures on the skin which form a protective barrier and aid in swimming.

Magnified images of porbeagle and spiny dogfish dermal denticles taken by scanning electron microscope. Images courtesy of Frank Thomas, MicroAnalysis Facility, GSC Atlantic.

Internal Anatomy

Seen in this picture of a blue shark are the liver, stomach and intestine. The oviduct, part of the female reproductive tract is also visible.

Upon incision of the belly from the pelvic fins to the pectoral fins the first organ encountered is the liver. The liver of sharks occupies most of the body cavity. This large, soft and oily organ can comprise up to 25% of the total body weight. It serves two functions within the shark. The first is as an energy store since all fatty reserves are stored here. The second function of the liver is to serve as a hydrostatic organ. Oils that are lighter than water are stored in the liver. This decreases the density of the body providing buoyancy to counteract the sinking tendency of sharks.

Aside from the liver, the stomach can be seen within the body cavity. Often found within the stomach are the contents of the sharks last meal. The stomach itself terminates at a constriction known as the pylorus, which leads to the duodenum and then to the spiral valve intestine. The spiral valve intestine is an internally coiled organ that increases the surface area across which nutrients can be absorbed. The spiral valve intestine empties into the rectum and anus which in turn empties into the cloaca. The claoca is the chamber where the digestive, urinary and genital tracts all open to the outside.

Some of the organs mentioned can be seen in this photograph of a mature male porbeagle shark. Also seen here is the epididymis, part of the male reproductive tract.

Also easily found within the body cavity is the pancreas. The pancreas is a digestive gland with two pink lobes. Secretions pass from this organ to the duodenum from the ventral lobe through a small duct.

There are two other organs that are visible but do not belong to the digestive system. The first is the spleen, which is a dark organ near the stomach that belongs to the lymphatic system. The second is the rectal gland, a small organ that opens by a duct into the rectum. It acts as a salt gland, removing excess sodium chloride (salt) from the blood. The secretion is a colourlesss solution of salt that is twice the concentration found within the blood plasma and higher than that of the surrounding saltwater.

Upon removal of the digestive organs the reproductive organs can be viewed. For details about the reproductive anatomy of sharks visit the Shark Reproduction page within this site.

- Date modified: