Socio-Economic Impact of the Presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes Basin

Prepared by

Salim Hayder, Ph.D.

Edited by

Debra Beauchamp

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Policy and Economics

501 University Crescent, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A Brief Overview of the Study Area

- Chapter 2: Literature Review

- Chapter 3: Methodology Adopted

- Chapter 4 - Baseline Values of Activities around the Great Lakes

- Water Use

- Raw Water Use

- Industrial Water

- Agricultural Water

- Commercial Fishing

- Recreational Fishing

- Recreational Hunting

- Recreational Boating

- Beaches and Lakefront Use

- Wildlife Viewing

- Commercial Navigation

- Oil and Gas

- Ecosystem Services

- Option Value

- Non-Use Value

- Aggregated Economic Contribution

- Limitations/Gaps Identified in the Study

- Chapter 5: Social and Cultural Values of the Great Lakes

- Chapter 6: Scenario Based on Biological Risk Assessment

- Chapter 7: Socio-Economic Impact Assessment

- Chapter 8: Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Matrix 1: Total Economic Valuation Flowchart

- Definitions

- Matrix 2: The Great Lakes - Total Economic Valuation Flowchart

- Matrix 3: Summary of Empirical Studies Used for Valuation of Economic Activities in the Great Lakes basin

- Annex 1: Selected Socio-Economic Indicators for Ontario

- Annex 2: Aboriginal identity population by Sexes, Age Groups, Median Age for Ontario and Canada

- Annex 3: Estimated Water Consumption and Values by Sector, Lake and Province for the Year 2008

- Annex 4: Landings and Landed Values of Commercial fisheries in the Great Lakes by Species and Lake in 2011

- Annex 5: Number of Fish Harvested All Anglers Who Fished on the Great Lakes, by Species and Lake, 2005

- Annex 6: Heat-Map - Commercial and Recreational Fishing for 20 and 50 Years

Chapter 7: Socio-Economic Impact Assessment

For this study, the socio-economic impacts that are direct consequences of the ecological outcomes of an introduction of Asian carp have been considered. These socio-economic impacts are tied to the DFO (2012) ecological risk assessment and form the basis for the socio-economic analysis.

DFO (2012) provided the scenario for the socio-economic impact analysis, both for the estimate of the impact as well as for a comparison of the values with those of the baseline. In order to estimate the socio-economic impact of the presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes, the study also heavily relied on the overall probability of introduction and the consequence scale developed in the ecological risk assessment.

In order to set the stage (scenario) for impact assessment, following DFO (2012), the study assumed that in the absence of added prevention and protection, Asian carp will arrive, establish population, survive and spread due to the availability of suitable food, thermal and spawning habitats, and high productivity embayments in the Great Lakes basin.

As stated in Chapter 3, in addition to the results extracted from DFO (2012), expert scientific opinion was sought from a group of scientists involved in the DFO (2012) assessment, in order to establish a defensible foundation for the socio-economic impact assessment. The discussion largely focused on: (i) the activities/sectors that might be impacted; (ii) the impact trend over 20 years and 50 years; and (iii) permissible ways to use the quantitative scales of the overall probabilities for the impact analyses.

Based on the results reported in DFO (2012), Cudmore, Mandrak, Dettmers, Chapman, and Kolar (2012), and subsequent discussion with scientists, the study identified that, of the list of activities covered in the calculation of baseline values generated by the Great Lakes basin, Asian carp will cause moderate to high damage to commercial fishing, recreational fishing, recreational boating and the beaches and lakefront use sectors/activities during the period covered. Asian carp will cause either negligible or low impact on water use, recreational hunting, commercial navigation and oil and natural gas extraction sectors/activities. Moreover, it was also found that the extent of damage is lake specific and is directly linked to the ecological damages as well as to the level of activities dependent on the lakes.

The next section of this chapter provides a detailed discussion of the degree of damage caused by Asian carp in the Great Lakes by major activity impacted.

Commercial Fishing

In order to assess the impact on commercial fishing and related activities, it was necessary to project the expected ecological consequences on native species commercially fished in the Great Lakes. Cudmore et al. (2012) found that Asian carp were capable of causing significant changes in plankton (the base of the Great Lakes food web) and in phytoplankton compositions, with substantial repercussions for the aquatic ecosystem. The harmful ecological effects due to the presence of Asian carp are also widely documented in pertinent literature. The most common effects include decline in: (i) planktivorous (feeding primarily on plankton) fish species; (ii) fish diversity; and (iii) populations of several species with pelagic early life stages. Cudmore et al. (2012) concluded that if Asian carp became established in the Great Lakes with ample populations, a similar impact to those documented worldwide would be realized.

Cudmore et al. (2012) found that the diet of Asian carp (5-20% of its average 30-40 lb. body weight each dayFootnote 88) overlaps with that of native fish species. The competition for food resources would result in: (i) reduced abundance of near-shore planktivorous forage/prey/bait fishes (e.g. cisco, bloater, rainbow smelt) and adult piscivores (fish-eating species, such as lake trout), reduced growth rates, and reduced recruitment in Lake Superior; (ii) reduced abundance of near-shore planktivorous forage/prey/bait fishes (e.g. alewife, cisco, bloater, rainbow smelt, yellow perch) and adult piscivores (e.g. chinook salmon, lake trout, walleye, Northern pike), reduced growth rates, and reduced recruitment in Lake Huron; (iii) reduced abundance of planktivorous forage/prey/bait fishes (e.g. emerald shiner, gizzard shad, rainbow smelt, white perch), fishes with pelagic early life stages and adult piscivores (e.g. lake trout, rainbow trout, walleye, yellow perch), reduced growth rates, and reduced recruitment in Lakes Erie and St. Clair; and (iv) depending on dreissenid (family of small freshwater mussels) biomass, reduced alewife biomass by up to 90%, which could damage salmonine populations in Lake Ontario. It was also found that Asian carp show high flexibility in terms of food habits. They are capable of changing food behaviour in accordance with food availability, without any impact on their high survival rate.

Based on the results reported in DFO (2012) and Cudmore et al. (2012), the presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes could cause damage to commercial fishing and related activities as follows:

Flowchart 1: Impact on Commercial Fishing Resulting from the Presence of Asian carp

Description

Flowchart 1 is titled “Impact on Commercial Fishing Resulting from the Presence of Asian carp.” The top element is “Asian carp” and is shown to have two direct impacts: increasing operational costs (e.g. more clean-up and repair of nets) and increasing competition for food resources. Increasing operational costs has one direct impact, namely, decreasing profit. Decreased profit results in a decrease in harvesters’ revenue and vice versa. Decreased profit also results in decreased landings of native fish species. The increase in competition for food resources has two direct impacts: decreasing plankton and zooplankton and decreasing prey species. Both of these impacts contribute to a decrease in food availability, which in turn results in a decrease in commercially fished native fish species. This decrease also leads to decreased landings of native fish species. Decreased landings of native fish species have five direct impacts: 1) a decrease in harvesters’ revenue; 2) a decrease in the fish processing sector; 3) a decrease in fish exports and an increase in fish imports; 4) a decrease in complementary goods production; and 5) an increase in substitute goods production.

The presence of an Asian carp population would likely cause damage to the commercial fishing industry through both the supply and demand sides of the market.

As shown in the flow chart, the presence of Asian carp would increase costs and decrease revenues for commercial harvesters. It would increase the operational costs of commercial fishing industry (e.g. relocation of sites, frequent repair of nets), which would in turn reduce the fishing activities and profit earned by harvesters. The presence of Asian carp would also damage the commercial fishing industry through the expected impact on fishing revenue. The rationale is that the presence of Asian carp would increase competition for food resources with young and mature native species. Asian carp would reduce the plankton, zooplankton and prey species available for commercially harvested fish species. Prey species would be impacted through direct consumption by Asian carp as well as decreased food availability for themselves. Less food availability would adversely affect commercially targeted fish populations, which would in turn reduce the catches of commercially fished species and harvesters’ revenues/activities. The decrease in revenue would in turn reduce the level of gross profit and thereby create a circular flow of impact. From a demand perspective, the sector would also be adversely affected because of a reduced quality of native fish species, reflected through the smaller size of commercially targeted fish.

An analysis of harvest data for the year 2011 shows that 12,141 tonnes were harvested from the Great Lakes that year, generating a total landed value of $33.6 million (see Annex 4). Of the total harvest, Lake Erie accounted for 81.5% (9,894 tonnes), followed by Lake Huron with 13.9% (1,691 tonnes), Lake Superior with 2.9% (354 tonnes) and Lake OntarioFootnote 89 with 1.7% (203 tonnes). The major species harvested were perch (34.5%), rainbow smelt (22.1%), walleye (17.3%), lake whitefish (13.6%) and white bass (6.8%).

The current current study estimated that in 2018, the total present (market) value of the catches from Lakes Erie, Huron, Ontario, and Superior for the subsequent 20-year time period (2018 to 2038) would be $4.8 billion, based on inflation-adjusted market value. Of that total, Lake Erie accounted for 82.7% ($3.9 billion) followed by Lake Huron with 14.2% ($0.7 billion), Lake Superior with 1.7% ($82.4 million) and Lake Ontario with 1.4% ($65.0 million).

The current study also estimated that in 2018, the total present value of the catches from Lakes Erie, Huron, Ontario, and Superior for the subsequent 50-year time period (2018 to 2068) would be $10.3 billion, based on inflation-adjusted market value. Of that total, Lake Erie accounted for $8.6 billion, followed by Lake Huron with $1.5 billion, Lake Superior with $0.2 billion and Lake Ontario with $0.1 billion.

In terms of commercially harvested native fish species and based on observations of present Asian carp migration rates, it appears that Asian carp would be in direct competition with yellow perch and white bass, and that the same type of competitive interaction would occur to a lesser degree with whitefish, through benthic food (e.g. zooplankton) unavailability. Walleye, which has limited and variable reproduction, would be indirectly affected by the alterations in the food chain. Species of less commercial value, such as white sucker, rainbow smelt and northern pike, would likely be negatively affected by Asian carp through competition for food, and would decline. Degradation of water quality caused by Asian carp would also be a source of damage to populations of native fish species.

In order to estimate the impact of an arrival of Asian carp in the Great Lakes, the study applied the analyses for ecological consequences reported in DFO (2012) to the landings and market values for the time periods covered, and assumed that the ecological impact would similarly be transmuted to the species’ populations and landings. In addition, the study assumed the absence of any additional measures to prevent the presence of Asian carp from the Great Lakes basin. Based on the foregoing, the study anticipated that the commercial fishing industry in Lakes Erie, Huron and Ontario, which accounted for $4.7 billion of the total net present value of $4.8 billion (98.6% of total), would be moderately affected with high to moderate uncertainty in 20 years starting 2018.Footnote 90 Only commercial fishing in Lake Superior, which accounted for $65 million of the total (1.4% of total), is anticipated to have low impact with high to moderate uncertainty.

Description

Table 8 is titled “Estimated Present Values ($000) of Market Values in Commercial Fishing in 20 and 50 Years by Lake” and is sourced from a Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region. The table has five columns. The first is captioned “Variables”; the second “Superior”; the third “Huron”; the fourth “Eerie”; the fifth “Ontario” and the sixth “Total.” There are two rows under “Variables” captioned “20 Years” and “50 Years.” Superior’s 20-year value is $64,998 and its 50-year value is $141,544. Huron’s 20-year value is $672,238 and its 50-year value is $1,463,917. Eerie’s 20-year value is $3,929,996 and its 50-year value is $8,558,253. Ontario’s 20-year value is $82,443 and its 50-year value is $179,535. The total 20-year value is $4,749,676 and the total 50-year value is $10,343,248.

| Variables | Superior | Huron | Erie | Ontario | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Years | $64,998 | $672,238 | $3,929,996 | $82,443 | $4,749,676 |

| 50 Years | $141,544 | $1,463,917 | $8,558,253 | $179,535 | $10,343,248 |

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region.

Table 8 shows that for the fifty year interval ending in 2068, the impact on the commercial fishing industry in Lakes Erie, Huron and Ontario, (which accounted for $10.2 billion of the total net present value of $10.3 billion (98.6%)), would be high, with moderate to high uncertainty. Only commercial fishing in Lake Superior, which accounted for $142 million of the total (1.4%), would be moderately affected, with moderate to high uncertainty.

The extent of the impact on commercial fishing by Great Lake is also related to the size and the depth of the lake. For example, 30% of the whitefish population spawns in Lake Erie. As it is the shallowest of all the Great Lakes, the impact on native fish species is anticipated to be higher because of more interaction between Asian carp and native fish species.Footnote 91 Moreover, some species (e.g. lake whitefish) have already been declining for some time because of other pernicious forces in place (e.g. zebra mussel). Any further decline exacerbated by Asian carp could render commercial fishing operations unsustainable, abolishing the commercial fishing industry from Lake Erie (which accounted for 81.5% of the catches in 2011), and subsequently from the entire Great Lakes.

As the commercially harvested fish species are impacted by the presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes Basin, it is anticipated that all sectors associated with commercial fishing through forward and backward linkages would be proportionally impacted (e.g. food processing and export sectors). For example, the detrimental impact on the commercially harvested freshwater species would damage the freshwater fish processing sector (captured in market value), reduce (increase) international exports (imports) of freshwater fish and fish products, increase pressure on the freshwater fish species sourced from other jurisdictions in Canada, and to some extent, hamper the competitive environment in the food sector in the regional economy and in Canada overall.

From an export perspective, the major freshwater species internationally exported from Canada were perch, whitefish, pickerel, trout, pike and smelt in 2011; together these species represented 75.7% of the total freshwater export.Footnote 92 In 2011, Ontario exported 14,682 tonnes of freshwater fish product that yielded a total export value of $89.0 million.Footnote 93 Exports of freshwater species from the Great Lakes, particularly whitefish, pickerel, mullet and pike, face competition from harvests elsewhere in Canada, international competitors and other related products.

The impact of Asian carp in the Great Lakes would possibly trigger some (re)distributional effects in terms of production and employment, which might hamper the competitive environment. This is due to the presence of substitute/complementary products to freshwater species from the Great Lakes, which provide competing protein choices to fish at restaurants and supermarkets. For example, when the commercial fishing industry is impacted in a manner that adversely affects both the quality and price, consumers always have the potential to switch away from freshwater products to favourably priced substitute products (e.g. marine fish, chicken and beef). The higher demand for substitute products will result in higher levels of production, value added and employment in the substitute sectors and lower levels of production, value added and employment in commercial fishing sector.

An increased abundance of Asian carp could create income-generating opportunities, which might partially offset loss due to the reduced abundance of commercially harvested native fish species. So far, however, the commercial value of Asian carp has been quite low and much less than the native fish they would replace.Footnote 94

The impacts discussed above are anticipated to be, by and large, proportional to the ecological consequences reported in DFO (2012) and Cudmore et al. (2012). It is also noteworthy that given the immense size of the Great Lakes and its complex ecosystems and food webs, a proper forecast on the magnitude of Asian carp impact, as well as the timeline for that impact to emerge on native fish abundance, is quite challenging.Footnote 95 For example, if the actual rate of arrival/migration differs from the predicted rate in DFO (2012) and Cudmore et al. (2012), both magnitude and realization of impact time will differ markedly.

Recreational Fishing

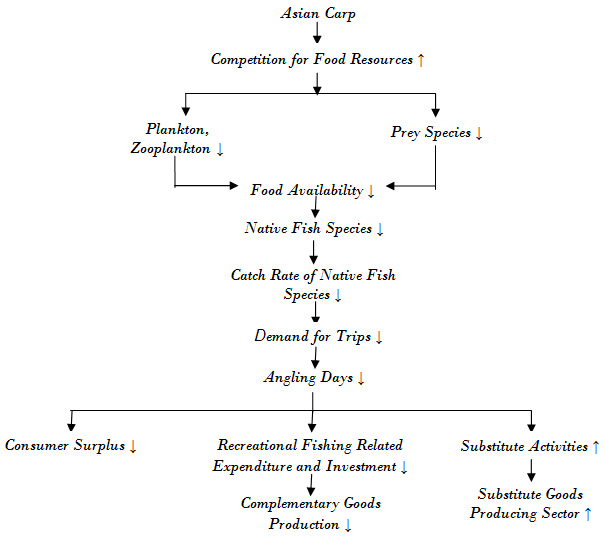

In order to estimate the impact of Asian carp presence on recreational fishing in the Great Lakes basin, it was necessary to determine how angler days would be reduced due to a deterioration of angler day quality. Based on the results reported in DFO (2012) and Cudmore et al. (2012), the presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes Basin would damage recreational fishing activities as follows:

As shown in the flow chart, the rationale is that if catch rates were reduced by decrease in fish populations, demand for trips would likely decrease proportionally, which would in turn lead to a decrease in angling days, and hence a decrease in the recreational fishing activities in the Great Lakes, measured by a decrease in expenditures related to recreational fishing and consumer surplus.

The anglers in the Great Lakes are made up of (i) Canadian residents of Ontario; (ii) Canadians non-resident to Ontario; and (iii) foreign anglers visiting Canada. DFO (2008) found that in 2005, of the total 4.8 million days fished, resident anglers accounted for about 4.2 million days, while non-resident Canadian anglers accounted for 23,412 days fished in the Great Lakes basin. Foreign anglers accounted for the remaining 11.5% of days (554,000).Footnote 96

Flowchart 2: Impact on Recreational Fishing Resulting from the Presence of Asian carp

Description

Flowchart 2 is titled “Impact on Recreational Fishing Resulting from the Presence of Asian carp.” Asian carp is the top element with a direct impact of increasing competition for food resources, which in turn decreases plankton and zooplankton and decreases prey species. Both of these decreases result in decreased food availability, causing a decrease in native fish species. Fewer native fish species mean a decreased catch rate of these species, resulting in a decrease in demand for trips. Less demand results in a decrease in angling days, which in turn causes a decrease in consumer surplus, a decrease in recreational fishing related expenditure and investment, and an increase in substitute activities. When recreational fishing related expenditure and investment drop, so does complementary goods production, and when there is a jump in substitute activities, there is also a jump in the substitute goods producing sector.

Description

Table 9 is titled “Major Purchases/Investments and Direct Expenditures ($000) by Type of Anglers and Lake, 2005” and is sourced from DFO 2008. The table has seven columns. The first is captioned “Variables”; the second “Lake Ontario”; the third “Lake Eerie”; the fourth “Lake St. Clair”; the fifth “Lake Huron”; the sixth “Lake Superior”; the seventh “St. Lawrence River”; and the eighth “Great Lakes System.” Variables are divided under two main rows “Major Purchases/Investments,” sub-divided by resident angler, non-resident angler and foreign angler”, and “Direct Expenditures,” also sub-divided by resident angler, non-resident angler and foreign angler. The major purchases/investments for Lake Ontario total $47.97 thousand, broken down as follows: $47,430 for resident angler, $123 for non-resident angler and $417 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for Lake Ontario total $44.93 thousand, broken down as follows: $39,226 for resident angler, $1,396 for non-resident angler and $4,305 for foreign angler. The grand total for Lake Ontario is $93 thousand. The major purchases/investments for Lake Eerie total $50.76 thousand, broken down as follows: $45,924 for resident angler, no value for non-resident angler and $4,840 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for Lake Eerie total $33.37 thousand, broken down as follows: $29,368 for resident angler, $2 for non-resident angler and $4,001 for foreign angler. The grand total for Lake Eerie is $84 thousand. The major purchases/investments for Lake St. Clair total $14.17 thousand, broken down as follows: $14,125 for resident angler, $20 for non-resident angler and $25 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for Lake St. Clair total $13.91 thousand, broken down as follows: $8,157 for resident angler, $1 for non-resident angler and $5,751for foreign angler. The grand total for Lake St. Clair is $28 thousand. The major purchases/investments for Lake Huron total $69.19 thousand, broken down as follows: $62,093 for resident angler, $2 for non-resident angler and $7,095 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for Lake Huron total $92.13 thousand, broken down as follows: $69,685 for resident angler, $357 for non-resident angler and $22,087 for foreign angler. The grand total for Lake Huron is $161 thousand. The major purchases/investments for Lake Superior total $10.29 thousand, broken down as follows: $7,521 for resident angler, no value for non-resident angler and $2,772 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for Lake Superior total $17.06 thousand, broken down as follows: $9,108 for resident angler, $42 for non-resident angler and $7,912 for foreign angler. The grand total for Lake Huron is $27 thousand. The major purchases/investments for the St. Lawrence River total $36.01 thousand, broken down as follows: $35,752 for resident angler, $2 for non-resident angler and $252 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for the St. Lawrence River total $13.21 thousand, broken down as follows: $7,707 for resident angler, $276 for non-resident angler and $5,225 for foreign angler. The grand total for the St. Lawrence River is $49 thousand. The major purchases/investments for the Great Lakes System total $228,394, broken down as follows: $212,846 for resident angler, $147 for non-resident angler and $15,401 for foreign angler. The direct expenditures for the Great Lakes System total $214,607, broken down as follows: $163,251 for resident angler, $2,075 for non-resident angler and $49,281 for foreign angler. The grand total for the Great Lakes System is $443,000.

| Variables | Lake Ontario | Lake Erie | Lake St. Clair | Lake Huron | Lake Superior | St. Lawrence River | Great Lakes System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Purchases/Investments | $47.97 | $50.76 | $14.17 | $69.19 | $10.29 | $36.01 | $228,394 |

| Resident Angler | $47,430 | $45,924 | $14,125 | $62,093 | $7,521 | $35,752 | $212,846 |

| Non-Resident Angler | $123 | - | $20 | $2 | - | $2 | $147 |

| Foreign Angler | $417 | $4,840 | $25 | $7,095 | $2,772 | $252 | $15,401 |

| Direct Expenditures | $44.93 | $33.37 | $13.91 | $92.13 | $17.06 | $13.21 | $214,607 |

| Resident Angler | $39,226 | $29,368 | $8,157 | $69,685 | $9,108 | $7,707 | $163,251 |

| Non-Resident Angler | $1,396 | $2 | $1 | $357 | $42 | $276 | $2,075 |

| Foreign Angler | $4,305 | $4,001 | $5,751 | $22,087 | $7,912 | $5,225 | $49,281 |

| Grand Total | $93 | $84 | $28 | $161 | $27 | $49 | $443,000 |

Source: DFO (2008).

For Canadian economy, if recreational fishing on the Great Lakes is impacted, there is an impact on resident and non-resident Canadian anglers’ expenditures and consumer surplus, and foreign expenditure that is associated with Great Lakes recreational fishing. As stated before, the argument here is that the non-resident, non-Canadian (foreign) consumer surplus is not a benefit to Canada, but the foreign expenditure is. The foreign expenditure would be lost if those visitors chose to spend their money in their own country instead of in the Canadian Great Lakes region.Footnote 97

The study estimated that in 2018, based on inflation-adjusted values for the subsequent 20-year time period, the total present value of the recreational expenditures and consumer surplus (excluding foreign consumer surplus) at Lakes Erie, Huron, Ontario, Superior, St. Clair and St. Lawrence would be approximately $11.8 billion (see Table 10). Of the total, Lake Huron accounted for $4.4 billion (37%), followed by Lake Erie (including St. Clair) with $3.0 billion (25%), Lake Ontario with $2.5 billion (21.0%), St. Lawrence with $1.3 billion (10.7%), and Lake Superior with $0.7 billion (6.0%).

Description

Table 10 is titled “Estimated Present Values ($Mil.) of Recreational Fishing Expenditures and Consumer Surplus in 20 and 50 Years by Lake” and is sourced from a Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region. The table has seven rows. The first is captioned “Variables”; the second “Superior”; the third “Huron”; the fourth “Eerie & St. Clair”; the fifth “Ontario”; the sixth “St. Lawrence”; and the seventh “Total.” There are two main rows under “Variables” captioned “20 Years” and “50 Years.” Each has three sub-rows captioned “Domestic Con. Surplus,” “Domestic Expenditure” and “Foreign Expenditure.” The 20-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Superior are $702 million, $57 million, $393 million and $252 million, respectively. The 50-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Superior are $1,528 million, $124 million, $856 million and $548 million, respectively. The 20-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Huron are $4,345 million, $543 million, $3,114 million and $688 million, respectively. The 50-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Huron are $9,462 million, $1,183 million, $6,781 million and $1,498 million, respectively. The 20-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Erie & St. Clair are $2,949 million, $305 million, $2,300 million and $344 million, respectively. The 50-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Eerie & St. Clair are $6,422 million, $663 million, $5,009 million and $750 million, respectively. The 20-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Ontario are $2,493 million, $304 million, $2,078 million and $111 million, respectively. The 50-year total, domestic con surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for Ontario are $5,429 million, $661 million, $4,525 million and $242 million, respectively. The 20-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for the St. Lawrence are $1,262 million, $102 million, $1,031 million and $129 million, respectively. The 50-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for the St. Lawrence are $2,749 million, $223 million, $2,245 million and $281 million, respectively. The 20-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for the Total column are $11,751 million, $1,311 million, $8,916 million and $1,524 million, respectively. The 50-year total, domestic con. surplus, domestic expenditure and foreign expenditure values for the Total column are $25,590 million, $2,854 million, $19,416 million and $3,320 million, respectively.

| Variables | Superior | Huron | Erie & St. Clair | Ontario | St. Lawrence | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Years | $702 | $4,345 | $2,949 | $2,493 | $1,262 | $11,751 |

| Domestic Con. Surplus | $57 | $543 | $305 | $304 | $102 | $1,311 |

| Domestic Expenditure | $393 | $3,114 | $2,300 | $2,078 | $1,031 | $8,916 |

| Foreign Expenditure | $252 | $688 | $344 | $111 | $129 | $1,524 |

| 50 Years | $1,528 | $9,462 | $6,422 | $5,429 | $2,749 | $25,590 |

| Domestic Con. Surplus | $124 | $1,183 | $663 | $661 | $223 | $2,854 |

| Domestic Expenditure | $856 | $6,781 | $5,009 | $4,525 | $2,245 | $19,416 |

| Foreign Expenditure | $548 | $1,498 | $750 | $242 | $281 | $3,320 |

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region.

As shown in Table 10, the study calculated that in 2018, based on inflation-adjusted market value for the subsequent 50-year time period, the total present value of the recreational expenditures and consumer surplus (excluding foreign consumer surplus) would be $25.6 billion. Of that total, Lake Huron accounted for $9.5 billion, followed by Lake Erie (including St. Clair) ($6.4 billion), Lake Ontario ($5.4 billion), St. Lawrence ($2.8 billion) and Lake Superior ($1.5 billion).

In terms of species caught in recreational fishing, DFO (2008) found that in 2005, the major species caught by anglers were perch (31.9%), bassFootnote 98 (23.2%), whitefish (8.1%), pike (5.0%), and troutFootnote 99 (9.0%)Footnote 100 (see Annex 5).

In the absence of additional measures to prevent the presence of Asian carp to minimize the damages to the recreational fishing activities in the Great Lakes basin, the study anticipated that in 20 years starting in 2018, resident and non-resident Canadian anglers’ expenditure and consumer surplus, and foreign expenditure associated with recreational fishing in Lakes Erie, Huron and Ontario would be moderately affected, with moderate to high uncertainty.Footnote 101 For Lake Superior the impact would be low, with moderate to high uncertainty.

Employing a 50 year horizon starting in 2018, the impact on resident and non-resident Canadian angler consumer surplus and foreign expenditure associated with recreational fishing in Lakes Erie, Huron and Ontario would be high, with moderate to high uncertainty. Lake Superior would be moderately affected, with moderate to high uncertainty.

As stated earlier, it is expected that damage to recreationally harvested fish species caused by the presence of Asian carp in the Great Lakes basin would be followed by some relocation of expenditures of resident and non-resident Canadians to other sectors in the economy.Footnote 102 With moderate to high uncertainty, the study estimated that over 20 years and 50 years starting 2018, the present value of the relocation of expenses by Canadians from Lakes Erie, Huron, Ontario and Superior would be in the amount of $7.9 billion and $17.2 billion, respectively.Footnote 103

In addition to damage from ecological consequences found in DFO (2012) and Cudmore et al. (2012), the presence of Asian carp might discourage recreational fishing through direct harm to people. Silver carp is reported to startle easily at the sound of a boat motor, leading them to leap out of the water and land in boats, and thereby damage property and injure boaters. They are reported to break fishing rods, windshields and other equipment in a boat. Furthermore, once they land in the boat, they leave slime, blood and excrement.

The jumping behavior of Asian carp might not only discourage people from fishing, but also result in a transfer of wealth from boat owners to service providers operating in the Great Lakes region. While Asian carp might raise the operational and maintenance costs of boat owners (e.g. installing protective equipment), the study recognizes that the additional costs borne on boat owners would be a mere transfer of resources from boat owners to those service providers.Footnote 104

Apart from recreational fishing, anglers also seek opportunities to enjoy other supplementary outdoor activities while on trips. The Canadian Tourism Commission (2006) found that relative to the average Canadian pleasure traveler, anglers were also more likely to go boating, swimming and wildlife viewing while on trips. Anglers were especially more likely to have attended sporting events (e.g., professional sporting events, amateur tournaments) and attractions with an agricultural or western theme (e.g., agro-tourism, equestrian and western events). Reduced recreational fishing and related activities will have economic impact to those whose livelihood depends on the development of this sector. The impacts on such subsidiary activities are anticipated to be notable, but are not quantified due to insufficient information.

Recreational Boating

Great Lakes boaters, water-skiers, and others who go out on the water for pleasure will be adversely affected by the presence of Asian carp through the hazards the fish present to boaters (e.g. injury to boaters), as described earlier in this study in the recreational fishing section, and by reduced opportunities for water sports, pleasure boating and sailing. Moreover, like recreational fishing, recreational boating in the Great Lakes will be impacted through higher operational and maintenance costs associated with boating in waters where Asian carp have become established.

Description

Table 11 is titled “Projected Present Values ($000) of Recreational Boating Expenditures and Consumer Surplus in 20 and 50 Years” and is sourced from a Fisheries and Oceans Canada Staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region. The table has five columns. The first is “Variables”; the second is “Boating Expenses”; the third is “Tourism”; the fourth is “Consumer Surplus”; the fifth is “Total”. There are two rows under the Variables column captioned “20 Years” and “50 Years”. The 20-year and 50-year values for boating expenses are $108,982,348 and $237,328,071, respectively. The 20-year and 50-year values for tourism are $37,696,090 and $82,089,811, respectively. The 20-year and 50-year values for consumer surplus are $6,234,075 and $13,575,786, respectively. The 20-year and 50-year values for the total column are $152,912,513 and $332,993,668, respectively.

| Variables | Boating Expenses | Tourism | Consumer Surplus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Years | $108,982,348 | $37,696,090 | $6,234,075 | $152,912,513 |

| 50 Years | $237,328,071 | $82,089,811 | $13,575,786 | $332,993,668 |

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region.

The study estimated that the present value of boaters’ consumer surplus and foreign expenditure associated with recreational boating in the Great Lakes basin was in the amounts of $43.9 billion and $95.7 billion, in 20 years and 50 years, respectively, starting in 2018 (see Table 11). In the absence of additional measures to prevent the presence of Asian carp to minimize the damages to the recreational boating activities in the Great Lakes basin, boaters’ consumer surplus and foreign expenditure associated with recreational boating in the Great Lakes would be jeopardized to an extent relative to the scope of the jumping behavior of silver carp.Footnote 105

Similar to recreational fishing, it is anticipated that there would be some relocation of expenses by resident/non-resident Canadians to other sectors due to the expected damage to recreationally boating and related activities.Footnote 106 The study estimated that the present value of the expenses for boating by Canadians in the Great Lakes was $109.0 billion and $237.3 billion, in 20 years and 50 years respectively, starting in 2018, and that this value would be relocated to some extent relative to the scope of the jumping behavior of silver carp.

Wildlife Viewing

Since Asian carp consume cladophora,Footnote 107 they may cause Cladophora mats in the Great Lakes basin to expand, particularly around the near-shore areas.Footnote 108 Decomposing Cladophora provides a breeding ground for enteric bacteria, including some pathogens which can produce dangerous toxins. Using traditional microbiological and DNA-based techniques, studies found that cladophora provided suitable habitat for indicator bacteria, and potentially for pathogens, to persist and grow. This may in turn impact beach water quality (GLSC Fact Sheet 2009).

Despite the Great Lakes clean-ups in the 1970s, there has been a resurgence of cladophorain the Great Lakes in recent years for a variety of reasons (e.g. zebra and quagga mussels, agricultural operations, sewage). Mass cladophora accumulations along shorelines have been documented to affect recreational activities (e.g. wildlife viewing), potentially influencing water quality, and causing significant health and economic concerns (GLSC Fact Sheet 2009). The presence of Asian carp will enhance cladophora build-up capacity in the Great Lakes, increase cladophora-related problems, pose increased health risk to Great Lakes users, and contribute to a decreased level of wildlife viewing activities around the Great Lakes basin.

The study estimated that the present values of resident wildlife viewers’ consumer surplus associated with wildlife viewing in the Great Lakes basin are in the amounts of $1.1 billion and $2.4 billion in 20 years and 50 years, respectively, starting in 2018 (see Table 12).

Description

Table 12 is titled “Estimated Present Values ($000) of Wildlife Viewing Expenditures and Consumer Surplus in 20 and 50 Years” and is sourced from a Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region. The table has five columns. The first is “Variables”; the second is “Viewing Expenses”; the third is “Tourism”; the fourth is “Consumer Surplus”; the fifth is “Total”. There are two rows under the Variables column captioned “20 Years” and “50 Years”. The 20-year and 50-year values for viewing expenses are $3,453,391 and $7,520,362, respectively. The 20-year and 50-year values for tourism are not available. The 20-year and 50-year values for consumer surplus are $1,108,425 and $2,413,789, respectively. The 20-year and 50-year values for the total column are $4,561,816 and $9,934,151, respectively.

| Variables | Viewing Expenses | Tourism | Consumer Surplus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Years | $3,453,391 | NA | $1,108,425 | $4,561,816 |

| 50 Years | $7,520,362 | NA | $2,413,789 | $9,934,151 |

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada staff calculation, Policy and Economics, Central and Arctic Region.

Note: NA – Not available.

In the absence of additional measures to prevent the presence of Asian carp from the Great Lakes basin, viewers’ consumer surplus associated with these activities would be to some degree jeopardized, relative to the extent of deterioration of water quality and cladophora-related problems caused by the presence of Asian carp.

Similar to recreational fishing/boating, it is anticipated that there would be some relocation of expenditures by resident Canadians to other sectors in the economy due to the expected damage to wildlife viewing activities.Footnote 109 The study estimated that the present values of the expenses for viewing by resident Canadians in the Great Lakes were $3.5 billion and $7.5 billion in 20 years and 50 years, respectively, starting in 2018, and that these values would be relocated relative to the extent of the problems caused by the presence of Asian carp.Footnote 110

Beaches and Lakefront Use

The impact the presence of Asian carp would present to beach and lakefront use can be linked to the increased accumulation of cladophora mats.Footnote 111

Similar to recreational fishing, boating and wildlife viewing, it is likely that there would be some relocation of expenditures by beach users to other sectors in the economy due to the expected damage to beaches and lakefront use activities that the presence of Asian carp would cause.Footnote 112 The study estimated that the present values of the expenses for beach use in the Great Lakes were $5.2 billion and $11.3 billion in 20 years and 50 years, respectively, starting in 2018, and that these values would be relocated relative to the extent of the problems caused by the presence of Asian carp.Footnote 113

Other Sectors

As stated above, based on DFO (2012), Cudmore et al. (2012) and subsequent discussions with scientists, the study found that Asian carp would likely have either negligible or no impact on recreational hunting,Footnote 114 water use, commercial navigation, and oil and natural gas extraction activities.

Ecosystem Services

The variability in ecosystem services might increase upon the presence of Asian carp. As firms/households generally prefer to avoid risk or to be compensated for the changes which might be seen as an additional impact of the presence of Asian carp.Footnote 115

Social and Cultural Impact

Over time, the presence of Asian carp to the Great Lakes basin could change lake ecosystems from ones dominated by native fish species to ecosystems dominated by carp, and has the potential to damage the public image of these lakes regionally, nationally and internationally. It would also harm the well-being of residents living close to such a unique natural resource.

Despite that Asian carp may present an opportunity for subsistence harvests and harvesters are adaptive to changing environment, Asian carp species may significantly damage subsistence harvests of native species from the Great Lakes and reduce the social, cultural and spiritual values of the lakes and of lake-related activities. Subsistence harvests may be impacted due to (i) change in ecosystem which may result in less native species as well as poor food quality for subsistence harvesters with negative impacts on subsistence harvesters and communities; and (ii) gaining access to subsistence fishing may be impaired and/or may require travelling greater distances which will increase costs of harvesting. This will weaken/obsolete traditional knowledge and observations, and inter-generational transfer of knowledge and culture and change ways of life. Finally, the presence of Asian carp may also encourage the increased level of (i) competition among subsistence harvesters/communities for fewer native fish species; and (ii) conflict and competition with recreational and commercial harvesters if changes causes fewer species availability. Quantitative assessments of these impacts are not feasible due to a lack of pertinent information.

- Date modified: